Abstract

This paper will explore the combined effect of restrictive voting policies as measured by the Cost of Voting Index (COVI), a measure developed by political scientists associated with States United Democracy Center and Northern Illinois University—on voter turnout in Presidential elections, paying specific attention to the impact of such policies on minority populations. It will explore the state-level relationships between the cost associated with voting policies and the voter turnout rate of racial groups in presidential elections over the period of 1996 to 2016, examining the question of how voting rights policies influence the turnout rate of minority voters in U.S. presidential elections.

The percentage of White voters who cast a ballot in the 2020 presidential election exceeded that of non-white voters by approximately 13 percentage points (Morris & Grange, 2021). On the national level, the disparity between the voter turnout rate of White and non-white voters in the United States presidential elections has varied over time. While this trend highlights the overall difference in voter turnout levels across the nation, the gap also varies widely by state.

States play a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of democracy in the United States due to the power enshrined in the U.S. Constitution allowing state legislatures to regulate the “Times, Places, and Manner” of elections (U.S. Const. art. I, § 4, cl. 1). As such, legislation implemented by states directly impacts voters’ access to casting a ballot. Recently enacted state laws that have placed more restrictions on registered voters’ ability to vote include legislation that has disenfranchised people convicted of felonies, enforced strict photo identification requirements, and made it challenging to cast an absentee ballot, among others. These policies have increased and sustained barriers to the ballot box, making it harder for registered voters to exercise their right to vote. Further, they have disproportionately burdened voters of color (Hajnal et al., 2016; Alvarez et al., 2008).

Other researchers have examined the effects of policy choices, such as polling location distance, vote by mail access, and voter ID requirements, on voter turnout in different election cycles. While these studies have highlighted the direct impacts of individual policies, laws that restrict access to the ballot often do not exist in isolation.

The election infrastructure that has been built in the United States was designed to reflect the democratic values the country was built upon and bolster the voice of individuals in their government. To continue upholding these values, it is important to understand how policy decisions shape the size and makeup of the electorate.

Background

Following the 2020 presidential election, former President Donald Trump questioned the validity of the election results on the national stage. The impact of the debate surrounding the results has penetrated American politics in the ensuing years and cascaded into a sentiment of distrust in election administration and integrity in the United States. Voters have expressed skepticism in the process of casting and counting ballots. This has been reflected in public opinion with the proportion of voters who believe that elections are administered well dropping almost 20 percentage points between 2018 and 2020 (Pew Research Center, 2022). Confidence in election administration has shifted along partisan lines. Republican trust in elections exceeded that of Democrats in 2018; however, Republican public opinion dropped almost 30 percentage points between 2018 and 2022, while Democratic trust in elections increased by more than 10 percentage points in the same timeframe (Pew Research Center, 2022). This shift has resulted in the trust gap shifting, with Democratic trust in elections exceeding that of Republicans by 22 percentage points in 2022 (Pew Research Center, 2022).

In attempts to reassure voters that the election process is safe, some state legislatures have enacted legislation aligning with public sentiment. In 2022 alone, eight states enacted 11 voting laws that restricted voters’ ability to vote—making it more difficult for individuals to register, cast a ballot, or stay on the voter rolls (Brennan Center, 2023). In the same year these 11 laws were passed, a total of 408 were considered by state legislatures across 39 states (Brennan Center, 2023). While the sharp rise in election-related distrust is a relatively recent phenomenon, the variation in election legislation across the states is not. The political environments of states differ greatly as a result of different demographic makeup and historical inequities, among other factors. Therefore, laws passed by state legislatures likely often reflect these political landscapes.

While the states do have significant power states to shape the election landscape in the United States, they are held accountable by federal statutes, including the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The VRA was passed in 1965 to ensure that enacted state election legislation does not on the basis of race inhibit the equal right to vote. Specifically, Section 5 of the VRA required states and localities with a history of racial discrimination among other considerations (covered jurisdictions were determined based on a formula outlined in Section 4(b) of the VRA) to clear any changes to election laws with federal authority prior to their implementation. This requirement acted as a form of accountability and protected minority voters from laws that could inflict disproportionate harm on their right to participate in elections. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that Section 5 of the VRA was unconstitutional in the case “Shelby County v. Holder.” According to the U.S Department of Justice, the U.S. Attorney General reviewed over 500,000 changes to election-related legislation between 1965 and 2013.

Prior to Shelby County v. Holder, a total of nine entire states and portions of seven other states were subject to pre-clearance. Immediately following the Shelby decision, states with large minority populations passed laws that restricted processes to cast a ballot. Campaign Legal Center found that seven out of 11 states with the highest Black turnout rate in the 2008 Presidential election enacted voting restrictions between 2013 and 2016 (Lang, 2016). The immobilization of Section 5 of the VRA by the Shelby decision has reduced the level of accountability imposed onto states and localities by the federal government, therefore reducing the protection of minority voters in these states.

The combined effect of the Shelby County decision, which removed a layer of legal protection for minority voters, alongside the rise in election distrust among voters have resulted in legislation passed by states that disproportionately harms voters of color and stifles their abilities to cast a ballot. This paper explores the relationship between such legislation and the gap in turnout rates across racial groups.

Literature Review

Studying the impact of voting laws on voter turnout rates is not new. Given the variation in state election and voting policies, a substantial body of literature has evaluated the impact of proposed and enacted individual laws on voter turnout. Previous work has focused on single policies—including the impact of voter ID laws, vote by mail access, polling place distance, early voting days, and registration options—as individual predictors of voter turnout. Additionally, prior research has examined both the effect of these drivers on the probability of individual voter turnout and aggregate voter turnout by geographic location.

According to the Voting Rights Lab, as of September 2024, the three states that do not offer early voting (Alabama, Mississippi, and New Hampshire) also require an excuse when applying for a vote by mail ballot and require a photo ID to cast a ballot. Additionally, two of the three states do not offer online voter registration as of 2024. This example is just one of many that illustrates how policies restricting voter access to the ballot rarely exist alone. The Cost of Voting Index captures many voting policies implemented by states, including voter ID laws, voter registration laws, absentee ballot policies, and early voting availability.

Existing literature exploring the individual effects of various voting policies on voter turnout rates has suggested that while each restrictive policy of focus has a negative effect on turnout, the size of the effect varies across policies. This paper studies the combined effect of different policies on voter turnout rate at the state level.

Voter ID Laws and Turnout Rates

As of this writing, 37 states have laws that request or require voters to show a form of identification when casting a ballot (Voting Rights Lab, 2023). The remaining states employ other methods to verify voter identity, such as signatures (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023). While voter identity verification ensures only one ballot is cast by each voter during an election, not all individuals have IDs, and the distribution of people without IDs varies by race and economic class. Vanessa M. Perez of Project Vote (2015) found that White people are more likely to have a government-issued ID than other racial groups. 9% of people who are White were found to not have a government-issued ID, while 27% of people who are Black and 17% of Hispanic people do not—indicating a large racial disparity. Additionally, people with low incomes are the least likely across income groups to possess a form of government-issued ID, reflecting an economic divide. A 15-percentage point gap separates the lowest and highest income groups; 81% of those with annual incomes $25,000 or less possess a valid ID compared to 96% of people with incomes $150,000 or more.

Scholars have explored the implications of such disparities by studying the effect of requiring or requesting an ID from voters on turnout. Evidence is mixed on the exact effect of voter ID laws on turnout rates. Hajnal, Lajevardi, and Neilson (2016), for example, found that strict photo identification laws have a negative impact on the voter turnout rates of voters who are Hispanic, Black, and mixed-race in primary and general elections. Similarly, Alvarez, Bailey, and Katz (2008), found that strict rules surrounding photo IDs at the polls reduced voter turnout, compared to policies that required one to state their name at the poll. In contrast, other researchers, including Mycoff, Wagner, and Wilson (2007), have found that photo ID requirements do not have an impact on voter turnout. Highton (2007) suggests that the lack of consensus among scholars indicates the level of enforcement of ID laws (strict versus non-strict) —rather than just the presence of such laws—is an important consideration when studying the effect voter ID policies have on turnout, rather than just the presence of such laws.

Voter Registration Laws and Turnout Rates

Voter registration laws take many different forms across the states. Examples include same-day voter registration, automatic voter registration, online registration, and the number of days before an election that a voter must be registered. As of this writing, 21 states do not allow for same-day registration of any form, seven states do not permit online voter registration, 24 states require a voter to be registered at least two weeks before Election Day, and 25 do not permit automatic voter registration (Voting Rights Lab, 2023).

Previous research has found that policies that make registration more accessible to voters—such as automatic voter registration, online registration, and same-day registration—result in increased voter turnout rates. McGhee, Hill, and Romero (2021) found that automatic voter registration increases the turnout rate of eligible voters, and the effect of such a policy gradually increases the longer the policy is in place. Additionally, a comprehensive look at historic registration laws that arose between 1896 and 1916 by Rosenstone and Hansen (1993) found that voter turnout in the North dropped by 17 percentage points as registration laws were instituted, suggesting that restrictions to registration have a negative effect on turnout of voters. Ansolabehere and Konisky (2006) compared the voter turnout rates of counties in New York in 1965 and Ohio in 1977, when these states imposed requirements on registration. They compared turnout in counties that did not have registration requirements prior to the state imposing them to turnout in counties that had adopted registration requirements prior to the states imposing them. They found that registration requirements had a negative effect on turnout and the immediate effect of such a law was a decrease in turnout of 7 percentage points.

Voting Convenience and Voter Turnout

Some states have adopted no excuse absentee ballots and early voting policies, including most recently during a global pandemic, while others have not. As of this writing, 14 states require a reason to vote by mail and three states do not allow early voting, meaning that in some states, voters who do not meet the eligibility requirements to vote by mail have to vote in- person on Election Day (The Voting Rights Lab, 2023).

The Census Bureau examined the use of early and mail-in voting by race from 2014 to 2022 and found that minority groups utilize these methods at higher rates than White voters (Fabina, 2023). About 67% of Asian voters, 58% of Hispanic voters, 48% of White voters, and 46% of Black voters used these methods. Given the difference in the proportion of voters who rely on these methods of voting by race, existing literature has examined how such policies impact turnout rates. McGhee, Paluch, and Romero (2022) found that making it easier for voters to vote by mail increased voter turnout both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. McDonald, Smith, Shino, and Mucci (2023) found the same, highlighting that states with greater usage of mail voting experience higher overall voter turnout. Similarly, Kaplan and Haishan (2020) found as the number of early voting days available in a state increase, voter turnout also increases.

Various Policies and Voter Turnout

The key independent variable of the current study, the Cost of Voting Index, considers voter ID laws, voter registration laws, and voting convenience. While this measure captures the combination of such policies, it is not a holistic representation of state-level election policy choices that can influence turnout rates. Dyck and Gimpel (2005), for example, examined polling place distance and found that voters who were located closest to a polling location were 25% more likely to vote than other voters. Similarly, a case study conducted in Los Angeles by Brady and McNulty (2011) observed voting precinct locations before and after policies required changes. They found that following the move of the precinct, as distance from the polling place increased, voter turnout decreased. Research suggests that given the other barriers that may require voters to vote in person on Election Day, physical proximity to a polling place can play a significant role in increasing accessibility to the ballot.

The Present Study

The present study contributes to the aforementioned literature by examining the combined effect of multiple types of voting policies as measured by the Cost of Voting Index. COVI is utilized as the key independent variable for estimating the effect of such policies on the voter turnout rates of minority voters across states over time. Measuring voting rights policies using this index accounts for and highlights that policies that increase the burden of casting a ballot on voters do not exist alone and seeks to examine the combined effect of these policies.

Conceptual Framework

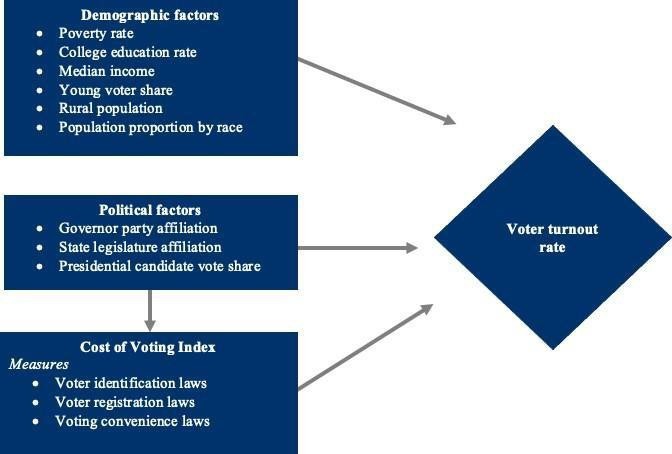

Based on extant research measuring the impact of individual election and voting rights policies on voter turnout rates, we should expect that as costs associated with voting increase across states, voter turnout levels across all subgroups will decrease. As noted in the literature review, policies that restrict voters from registering to vote and policies that reduce access to casting a ballot have a negative effect on voter turnout rates. Individually, these policies have a small to moderate effect size on voter turnout rates; as such, we should expect that the aggregate effect on voter turnout will have a moderately negative effect on turnout rates and will have larger effects on minority voters in comparison to their White counterparts. To control for varying factors that influence voter turnout and other factors that influence the types of policies passed in a state, demographic and political control variables will be included in the model. All independent variables and their expected relationship to the dependent variable, voter turnout rate, can be seen in Figure 1.

The Cost of Voting Index, created by researchers Michael J. Pomante II, Ph.D. and Scot Schraufnagel, was constructed utilizing principal component analysis and considers 68 voting and election policies decided by states. These 68 variables can be grouped into three main categories: voter identification requirements, voter registration laws, and voting convenience laws to provide an overview of the main index inputs.

- Voter identification requirements: Some states have implemented photo identification requirements for voters to cast a ballot with the stated goal of strengthening election security. As of September 2024, 17 states have policies that require voters to present photo identification to cast a ballot; 20 additional states request photo identification but are less strict in implementation than the states that require identification.

- Voter registration laws: The National Voter Registration Act of 1993, colloquially known as the Motor Voter Law, established a federal policy of giving individuals the opportunity to register to vote or change their registration when they interface with certain state agencies, including the Department of Motor Vehicles. Some states have since established other policies to ease the registration process for voters, including online registration, pre-registration (registration before voters turn 18), and same-day voter registration. As of this writing, seven states do not provide online voter registration, one state does not allow voters to pre-register to vote, and 29 states require voters to register before Election Day.

- Voting convenience laws: The COVI considers voting convenience as access to casting a ballot. Voting convenience includes the average number of hours polls are open, the number of early voting days, the permanence of absentee ballot requests, and restrictions on requesting an absentee ballot. As of this writing, 22 states place additional restrictions on requesting an absentee ballot, 14 require an excuse to vote by mail, three do not provide early voting, and six allow for just three to seven days of early voting.

Political factors

Laws impacting voter turnout enacted by state legislatures or by ballot initiative are likely influenced by political factors. The political factors of note are the partisan demographics of the state’s voters and the party affiliation of state leaders (legislators and governor). Voters and legislators play a role in shaping the political environment and therefore the laws that are enacted in a state. The governor is the final person in a state to sign off on or veto a bill passed by the legislature (barring the governor’s decision not being overridden).

Recognizing divides in how each major political party views elections and voting, the party affiliation of the governor likely plays a role in shaping the laws that are passed. In relation to the passage of restrictive voting laws, Hicks et al. (2015) found that states with Republican legislatures and governors were more likely to adopt restrictive voting reforms. Morris—of the Brennan Center—similarly found in 2022 that in racially diverse states controlled by Republicans, legislatures are much more likely to pass such policies.

Demographic Factors

Voter turnout rates vary across different demographic groups. As such, controlling for these differences will help isolate the effect of the key independent variable: COVI. Important demographic features other scholars have found to be important in predicting voter turnout include poverty rate, college education rate, state median income, youth population, rural population, and population proportion by race.

Existing research suggests that voters internally grapple with the cost-benefit analysis of participating in an election before choosing to cast a ballot. The costs and benefits of political engagement vary across demographic groups at both the individual and community level, and as such, so does the decision to cast a vote. Research has found, for example, that areas with high populations of college-educated voters, employed voters, higher income levels, and older voters are associated with higher voter turnout (Pew Research Center, 2022). Voter turnout varies by race, with White voters’ national turnout rate exceeding that of minority voters by approximately 13 percentage points. In contrast, voter turnout is lower in areas with high poverty rates and large rural areas (Barnes, S.G. 2021; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute 2023).

Variable Overview

Table 1 below describes each of the variables included in the models.

Table 1: Variable descriptions

|

Variable |

Description |

|

Dependent Variable |

|

|

Voter Turnout Rate |

A continuous variable measuring the percentage of registered voters who voted in the respective election by state. These estimates were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey Voting and Registration Supplement. |

|

Key Independent Variable |

|

|

Cost of Voting Index |

A continuous variable measuring the cost associated with voting in each respective election by state, ranging from -2.7 to 1.8, where a higher number indicates a higher cost associated with voting. This index was constructed using principal component analysis by academic researchers and takes multiple voting laws into account. This data was obtained from the Cost of Voting Index website. |

|

Political Variables |

|

|

Governor Party Affiliation |

A dichotomous variable, where 0 indicates a Republican and 1 indicates a Democrat, measuring the party affiliation of a state’s governor in each respective election. This data was obtained from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. |

|

Democratic State Legislature Affiliation |

A dichotomous variable, where 0 indicates a Republican or a split- party state legislature affiliation and 1 indicates a Democratic state legislature affiliation. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Statistical Abstract of the United States. |

|

Split-Party State Legislature Affiliation |

A dichotomous variable, where 0 indicates a Republican or a Democratic state legislature affiliation and 1 indicates a split-party state legislature affiliation. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Statistical Abstract of the United States. |

|

Democratic Presidential candidate vote share |

A continuous variable measuring the vote share received by the Democratic presidential candidate in a state in each respective election year. This data was obtained from the website 270towin. |

|

Republican Presidential candidate vote share |

A continuous variable measuring the vote share received by the Democratic presidential candidate in a state in each respective election year. This data was obtained from the website 270towin. |

Table 1: Variable descriptions (continued)

|

Variable |

Description |

|

Demographic Variables |

|

|

Poverty Rate |

A continuous variable measuring a state’s poverty rate, the percentage of households living at or below the Federal Poverty Level, in each respective election year. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. |

|

Median Income |

A continuous variable measuring the real median household income in each state in each respective election year. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. |

|

College Education Rate |

A continuous variable measuring a state’s college education rate, the percentage of adults, age 21 and older, who hold a four-year degree or higher, in each respective election year. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Decennial Census. |

|

Youth Population |

A continuous variable that measures the percentage of the state’s population that is aged 18 to 24. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. |

|

Rural Population |

A continuous variable that measures the percentage of the state’s population that lives in a Census-designated rural area. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Decennial Census. |

|

Population Proportion by Race |

Continuous variables (White, Black, and Asian) that measure the percentage of the state’s population that identifies as the respective race. This data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. |

Data and Methods

The analysis utilizes state-level data over the period of 1996-2016, for all 50 states, but just in the 6 years in which there was a presidential election. The data utilized to measure the dependent variable—minority voter turnout rate per state in the Presidential elections spanning from 1996-2016—is sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau. More specifically, the data comes from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration Supplement. The data measuring the key independent variable, the Cost of Voting per state in Presidential elections from 1996 – 2016, was created by two academics: Michael J. Pomante II, Ph.D. of States United Democracy Center and Scot Schraufnagel, Ph.D. of Northern Illinois University.1

The analysis controls for political and demographic factors, as described in the Conceptual Framework section, that are hypothesized to have individual relationships with voter turnout and/or the cost of voting. Data for governor party affiliation by state in 1996-2016 comes from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, and data for state legislature partisan affiliation by state from 1996-2016 come from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Statistical Abstract. Data on historical Presidential vote share by party come from the website, 270towin.2 Data on state demographic characteristics from 1996 to 2016 (poverty rate, college education rate, median income, youth population, rural population, and population proportion by race) comes from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.

Model overview

To analyze the proposed relationship between cost of voting in a state and the state voter turnout, four multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models are run—one multivariate OLS regression per race group (White, Black, and Asian) and one for the entire sample—to measure the effect of the cost of voting on each group and on the population as a whole.3 Given the expectation of state and time specific factors that drive voter turnout (such as the candidates running for office, among other societal factors that result in the relationship between such variables and turnout varying over time), an OLS model is best suited to account for such time variant relationships. The sample size of the data set is 300 observations (50 states * 6 general election years).

The following models are estimated:

White turnout:

white_turnout = 𝛽0 + 𝛽1 covi + 𝛽2 gov_party + 𝛽3 dem_legislature+ 𝛽4 split_legislature + 𝛽5

dem_presidential_vote + 𝛽6 rep_presidential_vote +𝛽7 poverty + 𝛽8 college_ed + 𝛽9 med_income

+ 𝛽10 youth_pop + 𝛽11 rural_pop + 𝛽12 racial_composition + 𝜇

Black turnout:

black_turnout = 𝛽0 + 𝛽1 covi + 𝛽2 gov_party + 𝛽3 dem_legislature+ 𝛽4 split_legislature + 𝛽5

dem_presidential_vote + 𝛽6 rep_presidential_vote +𝛽7 poverty + 𝛽8 college_ed + 𝛽9 med_income

+ 𝛽10 youth_pop + 𝛽11 rural_pop + 𝛽12 racial_composition + 𝜇

Asian turnout:

asian_turnout = 𝛽0 + 𝛽1 covi + 𝛽2 gov_party + 𝛽3 dem_legislature+ 𝛽4 split_legislature + 𝛽5

dem_presidential_vote + 𝛽6 rep_presidential_vote +𝛽7 poverty + 𝛽8 college_ed + 𝛽9 med_income

+ 𝛽10 youth_pop + 𝛽11 rural_pop + 𝛽12 racial_composition + 𝜇

Overall turnout:

overall_turnout = 𝛽0 + 𝛽1 covi + 𝛽2 gov_party + 𝛽3 dem_legislature+ 𝛽4 split_legislature + 𝛽5

dem_presidential_vote + 𝛽6 rep_presidential_vote +𝛽7 poverty + 𝛽8 college_ed + 𝛽9 med_income

+ 𝛽10 youth_pop + 𝛽11 rural_pop + 𝛽12 racial_composition + 𝜇

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics described have been weighted by population size, utilizing the Current Population Survey’s appropriate weights for the dataset analyzed.

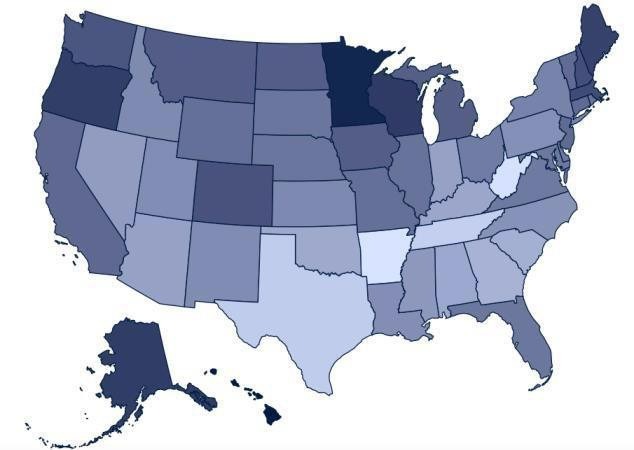

Dependent and key independent variables

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the dependent variables, key independent variable, and control variables. Over the time period of 1996 to 2016, across all states, the average voter turnout for White voters was 71 percent, which is higher than that of overall voters, Black voters, and Asian voters who had average voter turnout rates of 69, 67, and 54 percent, respectively. Figure B provides an overview of voter turnout rate by state by illustrating the average voter turnout rate for each state for overall voters between 1996 and 2016.

NOTE: The values range from low voter turnout rate (light color) to high voter turnout rate (dark color).

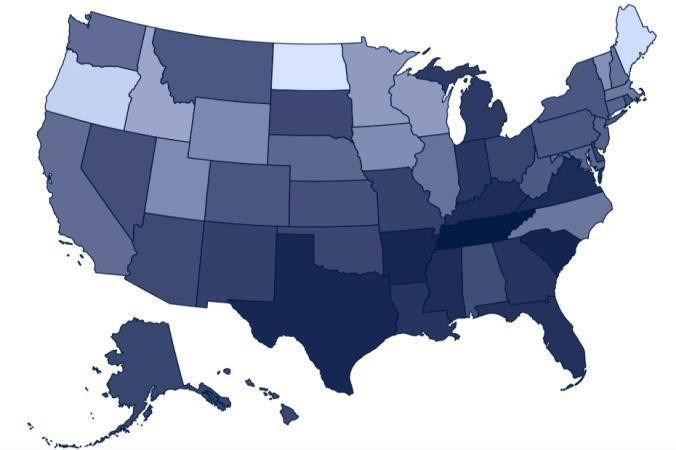

The key independent variable, the Cost of Voting Index, ranges from -2.78 to 1.77. A high COVI score indicates a high burden associated with voting; conversely, low COVI scores indicate low burdens associated with voting. Figure C shows the average COVI score for each state over the time period of 1996 to 2016.

NOTE: The values range from low COVI (light color, easier to vote) to high COVI (dark color, harder to vote).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for dependent, key independent, and control variables

|

Variable |

Mean |

Min |

Max |

SD |

|

Dependent Variable |

||||

|

Overall Voter Turnout Rate |

0.69 |

0.51 |

0.86 |

0.07 |

|

White Voter Turnout Rate |

0.71 |

0.52 |

0.86 |

0.06 |

|

Black Voter Turnout Rate |

0.67 |

0.14 |

0.91 |

0.01 |

|

Asian Voter Turnout Rate |

0.54 |

0.10 |

0.89 |

0.15 |

|

Key Independent Variable |

||||

|

Cost of Voting Index |

0.05 |

-2.78 |

1.77 |

0.68 |

|

Political Variables |

||||

|

Democratic State Legislature Affiliation |

0.35 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

0.48 |

|

Split-Party State Legislature Affiliation |

0.22 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

0.42 |

|

Democratic Presidential Candidate Vote Share |

0.47 |

0.22 |

0.72 |

0.93 |

|

Republican Presidential Candidate Vote Share |

0.49 |

0.27 |

0.73 |

0.10 |

|

Demographic Variables |

||||

|

Poverty Rate |

0.12 |

0.05 |

0.26 |

0.03 |

|

Median Household Income (in 2022 dollars) |

$67,000 |

$44,000 |

$93,000 |

$11,000 |

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for dependent, key independent, and control variables (Continued)

|

Variable |

Mean |

Min |

Max |

SD |

|

College Education Rate (% of adults age 21+ with a bachelor’s degree) |

0.27 |

0.14 |

0.43 |

0.05 |

|

Young Adult Population (% of population ages 18-25) |

0.13 |

0.10 |

0.29 |

0.02 |

|

Rural Population |

0.26 |

0.05 |

0.64 |

0.14 |

|

White Population Proportion |

0.78 |

0.21 |

1.00 |

0.16 |

|

Black Population Proportion |

0.10 |

0.00 |

0.38 |

0.10 |

|

Asian Population Proportion |

0.04 |

0.00 |

0.73 |

0.08 |

|

Estimated correlation coefficients:

*NOTE: The results are weighted.* |

||||

Control variables

The young adult population (18- to 24-year olds) consistently has lower rates of voter turnout relative to other age groups (Pew Research Center, 2022). Therefore, a measure of the proportion of the population that is young adults is included as a control variable. From 1996 to 2016 across all states, young adults made up on average 13% of the population.

Voters in rural areas often face physical barriers to casting a ballot (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute 2023). The percentage of a state’s population that lives in a rural area range from 5% to 64%.

Socioeconomic variables have been studied widely in existing literature about the cost- benefit consideration of voting. Within the present study’s data set, the average poverty rate across the time periods and states studied was 12%, with the lowest rate being 5% and the highest being 26%. The median household income across the states over the time period studied ranged from $44,000 to $93,000. Individuals’ educational attainment has been found to be a strong predictor of voting propensity (Pew Research Center, 2022). The average college education rate, the percentage of adults with at least a four-year degree, in each state over the studied time period was 27 percent.

Finally, Table 3 shows the distribution of governor party affiliation over time (of the states with data). The highest number of Republican governors (31) was in 2016, and the highest number of Democratic governors (21) was in 2008.

Table 3. Governor count by party, 1996-2016

|

Year |

Republican |

Democrat |

Independent |

|

1996 |

25 |

16 |

0 |

|

2000 |

25 |

15 |

2 |

|

2004 |

22 |

17 |

0 |

|

2008 |

18 |

21 |

0 |

|

2012 |

27 |

20 |

0 |

|

2016 |

31 |

16 |

1 |

Additional notable findings

Table 4 lists the states with the highest and lowest COVI score in each observed year.

Many of the states with the highest cost of voting over the period are geographically similar, located in the South. Among the states with the lowest cost of voting throughout the period, Oregon had the lowest cost of voting compared to other states in four of the six years in this study period.

Table 4. States with the highest and lowest COVI, 1996-2016

|

Year |

Highest COVI |

Lowest COVI |

|

1996 |

Texas |

Minnesota |

|

2000 |

Florida |

Oregon |

|

2004 |

Louisiana |

Oregon |

|

2008 |

South Carolina |

North Dakota |

|

2012 |

Tennessee |

Oregon |

|

2016 |

New Hampshire |

Oregon |

Results

The results of the regressions are summarized in Table 5. The table shows the results of a bivariate regression model (Model 1), estimated between the key independent variable and the voter turnout rate for each respective racial group; the table also shows the full, multivariate regression model (Model 2). Model 2 estimates the effect of the key independent variable and the control variables (which are grouped into the categories of political and demographic controls) on the voter turnout rate for each racial group.

Key independent variable

The bivariate model, without any control variables, identifies a negative relationship between the Cost of Voting Index and voter turnout rate across all racial groups. In other words, as the cost associated with voting increases, voter turnout rate decreases. In the bivariate model, this relationship is significant at the 0.10 level of significance for overall, White, and Asian voters. In all three models, a one-point increase in COVI is associated with a 0.3 percentage point decrease in voter turnout rate. 4For Black voters, the bivariate relationship is not statistically significant at the 0.10 level, meaning that it cannot be concluded by this model alone that there is a relationship between the cost of voting and voter turnout rate for Black voters.

The multivariate model also finds a negative relationship between the Cost of Voting Index and voter turnout rate across all groups. Again, as the cost associated with voting increases, voter turnout decreases. In this model, the Cost of Voting Index is significant at the

0.05 level of significance for overall, White, and Black voters. For overall and White voters, a one point increase in COVI is associated with a 0.2 percentage point decrease in voter turnout

Political control variables

The political control variables consist of the party affiliation of the state’s governor, party control of the state’s legislature, and the vote share in each state received by the Democratic or Republican presidential candidate. These variables measure the political climate within a state and the political attitudes of the voters and legislators who craft and implement policies. For each racial group, the governor’s party affiliation is not related to the voter turnout rate of each group at a statistically significant level. State legislature party affiliation has a statistically significant negative relationship with voter turnout for overall, White, and Black voters at the 0.05 level. Democratically affiliated state legislatures are associated with lower voter turnout rates than states with Republican state legislatures. Given that Hicks et al. (2015) found that Republican legislatures and governors were more likely to adopt restrictive voting reforms, there are perhaps other factors influencing the voter turnout rate outside of cost of voting. For overall voters, this difference is 0.3 percentage points, for White voters, 0.2 percentage points, and for Black voters, it decreases by 0.3 percentage point.

As the vote share for both the Democratic and Republican Presidential candidate increases, voter turnout increases at a statistically significant level (0.05) for overall, White, and Black voters. For overall voters, a 1% increase in the vote share for the Democratic presidential candidate is associated with a 0.55 percentage point increase in voter turnout, while a 1% increase in the vote share for the Republican candidate is associated with a 0.45 percentage point increase in voter turnout. For White voters, a one percentage point increase in the vote share for the Democratic presidential candidate is associated with a 0.48 percentage point increase in voter turnout, while a 1% increase in the vote share for the Republican candidate is associated with a 0.41 percentage point increase in voter turnout. For Black voters, a 1% percent increase in the vote share for the Democratic presidential candidate is associated with a 0.81 percentage point increase in voter turnout, while a 1% increase in the vote share for the Republican candidate is associated with a 0.48 percentage point increase in voter turnout.

Demographic control variables

The demographic control variables are state poverty rate, state median household income, percentage of adults over age 21 with a bachelor’s degree, state youth population (ages 18-25, measured in percentage of the total population), the percentage of the state’s population that lives in a rural designated area, and the racial composition of a state’s population. Across all racial groups, poverty rate and median household income are not significantly related to voter turnout rate.

College education rate has a significant and positive (at the 0.10 level) relationship to voter turnout rate for overall, White, and Black voters. For overall voters, a 1% increase in college education rate is associated with a 0.56 percentage point increase in voter turnout rate. For White voters, a 1% increase in college education rate is associated with a 0.63 percentage point increase in voter turnout. For Black voters, a 1% increase in college education rate is associated with a 0.47 percentage point increase in voter turnout rate.

The young adult population has a negative, statistically significant effect at the 0.05 level for Asian voter turnout. This variable does not have a statistically significant effect for any other group. For Asian voters, a one percentage point increase in the young adult population is associated with a 2.06 percentage point decrease in voter turnout.

The rural population, the percentage of a state’s population that lives in a Census defined rural location (defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as areas with a population of less than 2,500 people), has a positive, statistically significant relationship with voter turnout for overall, White, and Asian voters at the 0.05 level. For overall voters, a 1% increase in the rural population is associated with an 0.08 percentage point increase in voter turnout. For White voters, a 1% increase in the rural population is associated with a 0.06 percentage point increase in voter turnout. For Asian voters, a 1% increase in the rural population is associated with a 0.26 percentage point increase in voter turnout.

The percentage of each race among the total state population has a mixed statistically significant relationship at the 0.05 level across racial groups. For overall voters, a one percentage point increase in a state’s Black population is associated with a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the overall turnout rate; similarly, a one percentage point increase in a state’s White population is associated with a 0.05 percentage point increase in overall turnout rate. Additionally, a one percentage point increase in the state’s Asian population is associated with a 0.18 percentage point increase in the overall turnout rate. For Black voters, as the percentage of the population who identify as Black increases, voter turnout increases. A 1% increase in a state’s Black population is associated with a 0.32 percentage point increase in Black voter turnout. For White and Asian voters, the proportion of a state’s population that identifies as the same respective race does not have a statistically significant relationship with voter turnout rate for the respective group.

Table 5: Regression Results

|

Independent Variables |

Voter Turnout Rate |

|||||||

|

Model 1 – Binary |

Model 2 – Multivariate |

|||||||

|

Overall |

White |

Black |

Asian |

Overall |

White |

Black |

Asian |

|

|

Key Independent Variable |

||||||||

|

Cost of Voting Index (1) |

-0.03*** |

-0.03** |

-0.01 |

-0.03^ |

-0.02*** |

-0.02*** |

-0.03* |

-0.12 |

|

Political Controls |

||||||||

|

Democratic Governor Party Affiliation |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

||||

|

Democratic State Legislature Affiliation |

-0.03*** |

-0.02** |

-0.08*** |

0.00 |

||||

|

Split-Party State Legislature Affiliation |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

0.00 |

-0.01 |

||||

|

Democratic Presidential Candidate Vote Share |

0.55*** |

0.48*** |

0.81*** |

0.12 |

||||

|

Republican Presidential Candidate Vote Share |

0.45*** |

0.41*** |

0.48* |

-0.20 |

||||

Table 5: Regression Results (Continued)

|

Independent Variables |

Voter Turnout Rate |

|||||||

|

Model 1 – Binary |

Model 2 – Multivariate |

|||||||

|

Overall |

White |

Black |

Asian |

Overall |

White |

Black |

Asian |

|

|

Demographic Controls |

||||||||

|

Poverty Rate |

-0.03 |

0.12 |

0.61 |

0.10 |

||||

|

Median Household Income (in 2022 dollars, in ten-thousand dollars) |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

||||

|

College Education Rate (% of adults age 21+ with a bachelor’s degree) |

0.56*** |

0.63*** |

0.47^ |

0.40 |

||||

|

Young Adult Population (% of population ages 18-25) |

-0.07 |

-0.10 |

-0.01 |

-2.06*** |

||||

|

Rural Population (2) |

0.08** |

0.06* |

0.06 |

0.26** |

||||

|

Racial Composition (% race among the total population) |

White: -0.05^ Black: -0.17*** Asian: 0.18*** |

0.01 |

0.32*** |

-0.04 |

||||

Table 5: Regression Results (Continued)

|

Constant |

0.69*** |

0.70*** |

0.68*** |

0.56*** |

0.09 |

0.05 |

-0.17 |

0.68* |

|

Observations |

300 |

296 |

289 |

279 |

300 |

296 |

289 |

279 |

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.11 |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.56 |

0.47 |

0.14 |

0.10 |

|

Significance: 0.001 (***) / 0.01 (**) / 0.05 (*) / 0.1 (^) |

||||||||

|

||||||||

Discussion

The gap in voter turnout rates between White and nonwhite voters at the national level has grown in both Presidential and midterm elections in the United States, with the turnout rate of White voters consistently exceeding that of nonwhite voters (Morris and Grange, 2024). Such disparities in voter turnout leads to an overrepresentation of White voters at the polls. To mitigate these disparities, policymakers first need to understand what is driving them.

The results of the analyses are in line with the hypothesis that there is a modest, negative relationship between the cost associated with voting and voter turnout rate for overall voters, White voters, and Black voters. Such a relationship is not identified for Asian voters. The direction and strength of the relationship between the cost associated with voting and voter turnout rate suggests that restrictive voting policies are prohibitive across multiple racial groups but are most impactful for Black voters. The cost of voting has the greatest impact on the voter turnout rate of Black voters; states with more restrictive voting policy regimes are associated with more extreme decreases in the voter turnout rate of Black voters than any other racial group. These results are consistent with the studies that suggest states with policies that restrict voter access to casting a ballot have lower voter turnout rates than states with policies that do not bar voters from doing so (McDonald et al., 2023; McGhee et al., 2022; Kaplan and Haishan, 2020; Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; Alvarez et al., 2008; and Hajnal et al., 2016).

The other factors that were hypothesized to have a relationship with voter turnout rate across racial groups are found to mostly align with expectations from previous studies. State population with a college education, state young adult population, state rural population, and state racial composition all yielded results in alignment with previous research (Pew Research Center, 2022). States with higher college education rates have higher voter turnout rates than states with lower college education rates. College education rate has the strongest positive impact across racial groups on the voter turnout rate of White voters. The young adult population in a state has the strongest negative impact across racial groups on the voter turnout rate of Asian voters. The racial composition of a state has the strongest positive impact across racial groups on the voter turnout of Black voters. Being located in a state that has a high density of Black voters is associated with increased voter turnout for Black voters.

On the contrary, other factors had results that were inconsistent with prior research. The effect of a state’s rural population on voter turnout is positive and most impactful on the turnout rate of Asian voters, a finding that was out of line with previous research (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2021). Additionally, the results did not demonstrate a relationship between state poverty rate nor median household income and voter turnout rate in any racial group that was studied, a finding out of line with prior research (Pew Research, 2022).

Limitations

Quantitative analysis does not capture the nuance associated with unique individual experiences. Being registered to vote and having readily accessible resources to casting a ballot does not mean a person will decide to cast a ballot. While the current analysis accounts for a variety of political and demographic factors that prior studies have found to be associated with voting, it is nearly impossible to fully capture the complexity associated with the decision for a voter to cast a ballot. The analysis operates under the assumption that the reason for not casting a ballot in an election is that the voter cannot do so, not because they choose not to. Such an assumption fails to capture the portion of the population who intentionally decides to not participate in an election for any reason.

On a technical level, the absence of any relevant factor that is associated with a decrease in voter turnout rate, similar to the cost of voting, indicates omitted variable bias. Such bias means that the estimates of the relationship between the cost of voting and voter turnout rate could be overestimated. Additionally, while the research provides insight about the aggregate impact of restrictive voting regimes in states on voter turnout, one cannot directly extrapolate the effect of implementing a single policy on the voter turnout rate in a state.

Implications and future research

Due to the structure of the data from the U.S. Census Bureau that was utilized in constructing the full data set analyzed in this paper, analyses conducted were based only on three racial groups (White, Black, Asian, and overall voters) and did not account for ethnicity. The Hispanic population in the United States is large and incredibly diverse. Future research would benefit from the inclusion of such a demographic group.

The U.S. Census Bureau identifies 28 different nationalities that make up the Hispanic ethnicity. Similarly, the Asian race is composed of about 21 different ethnicities (Pena, et al., 2023; Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). Within the Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race, political history, experiences, and backgrounds of people who make up these groups vary greatly. Such variance suggests that these voting blocs are not homogenous and future research should examine the variation in voter turnout rate across these distinct identities.

The results of the analyses suggest that states with policies that make it harder for voters to cast a ballot relative to other states have lower voter turnout rates. Though the results do not provide a clear estimate of the exact effect of the implementation of a single policy on voter turnout rate, they do suggest that states should expect a decrease in voter turnout if they implement a policy that makes it harder to vote. Policymakers ought to consider the power and impact of voting policies on the shape of the electorate and therefore who pays the price for the costs of voting.

References

Alvarez, R. M., Bailey, D., & Katz, J. N. (2017). The effect of voter identification laws on turnout (Submitted). California Institute of Technology.

Ansolabehere, S., and Konisky, D.M. (2006). The introduction of voter registration and its effect on turnout. Political Analysis 14(1): 83-100.

Barnes, S.G. (2021). Waking the sleeping giant: Poor and low-income voters in the 2020 elections. Poor People’s Campaign.

Brady, H.E., and McNulty, J.E. (2011). Turnout out to vote: The costs of finding and getting to the polling place. The American Political Science Review 105(1): pp. 115-134.

DOI:10.1017/S000305541 0000596.

Brennan Center. (2023). Voting laws roundup: December 2022. Brennan Center. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup- december- 2022

Budiman, A. and Ruiz, N.G. (2021). Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/29/key-facts-about- asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/

Dyck, J.J., and Gimpel, J.G. (2005). Distance, turnout, and the convenience of voting. Social Science Quarterly 86(3): pp. 531-548.

Fabina, J. (2023). Voter registration in 2022 highest in 20 years for congressional elections. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/05/high-registration-and- early-voting-in-2022-midterm-elections.html

Fraga, B.L., Moskowitz, D.J., & Schneer, B.(2021). Partisan alignment increases voter turnout: Evidence from redistricting. Political Behavior 44.

Hajnal, Z., Lajevardi, N., and Nielson, L. (2016). Voter identification laws and the suppression of minority votes. Michigan State University Institute for Public Policy and Social Research. https://pages.ucsd.edu/~zhajnal/page5/documents/voterIDhajnaletal.pdf

Hicks, W.D, McKee, S.C., Sellers, M.D., & Smith, D.A. (2015) A principle or a strategy? Voter identification laws and partisan competition in the American States. Political Research Quarterly 68(1).

Highton, B. (2017). Voter identification laws and turnout in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science 20: 149-167. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051215-022822

Kaplan, E., and Yuan, H. (2020). Early voting laws, voter turnout and partisan vote composition: Evidence from Ohio. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12 (1): 32-60.DOI: 10.1257/app.20180192

Kaplan, J. (2021). United States governors 1775-2020. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://doi.org/10.3886/E102000V3

Lang, D. (2016). Five decades of section 5: How this key provision of the Voting Rights Act protected our democracy. Campaign Legal Center. https://campaignlegal.org/update/five- decades-section-5-how-key-provision-voting-rights-act-protected-our-democracy

McDonald, M.P., Mucci, J.K., Shino, E., and Smith, D.A. (2023). Mail voting and voter turnout. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy. Ahead of Print. http://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2022.0078

McGhee, E., Hill, C., and Romero, M. (2021). The registration and turnout effects of automatic voter registration. Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3933442

McGhee, E., Paluch, J., and Romero, M. (2022). Vote-by-mail policy and the 2020 presidential election. Research & Politics 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680221089197

Morris, K. (2022). Patterns in the introduction and passage of restrictive voting bills are best explained by race. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our- work/research-reports/patterns-introduction-and-passage-restrictive-voting-bills-are-best

Morris, K. & Grange, C. (2021). Large racial turnout gap persisted in the 2020 election. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/large- racial- turnout-gap-persisted-2020-election

Morris, K., and Grange, C. (2024). Growing racial disparities in voter turnout, 2008 – 2022. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research- reports/growing-racial-disparities-voter-turnout-2008-2022

Mycoff J. D., Wagner M. W., and Wilson D. C. (2009). The empirical effects of voter-ID laws: Present or absent? Political Science & Politics, 42, 121-126.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2023). Voter ID laws. National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/voter-id

Pena, J.E., Lowe Jr., R.H., and Rios-Vargas, M. (2023). Colombian and Honduran populations surpassed a million for the first time; Venezualan population grew the fastest of all Hispanic groups since 2010. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/2020-census-dhc-a-hispanic- population.html

Perez, V.M. (2015). Americans with photo ID: A breakdown of demographic characteristics. Project Vote. https://www.projectvote.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/AMERICANS- WITH-PHOTO-ID-Research-Memo-February-2015.pdf

Pew Research Center. (2022). Two years after election turmoil, GOP voters remain skeptical of elections. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/10/31/two- years-after-election-turmoil-gop-voters-remain-skeptical-on-elections-vote-counts/

Pomante II, M.J., Schraufnagel, S., and Q. Li. (2018). Cost of voting in the American states. Election Law Journal 17(3). DOI: 10.1089/elj.2017.0478.

Rosenstone, S.J., and Hansen, J.M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. New York: Longman.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute (2023) 2023 County health rankings national findings report: Cultivating civic infrastructure and participation for healthier communities. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Statistical Abstract of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed/tables/12s041 9.xls

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Current population survey. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html

U.S. Department of Justice. (2022). Section 5 changes by type and year. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/crt/section-5-changes-type-and-year

U.S. Const. art. I, § 4, cl. 1.

Voting Rights Lab. (2023). Issue areas. Voting Rights Lab. https://tracker.votingrightslab.org/issues/

270 to Win. (2020). Historical presidential elections. 270 to Win. https://www.270towin.com/historical-presidential-elections/

Footnotes

1 https://costofvotingindex.com/

2 https://www.270towin.com /

3 Due to the structure of the data collected, Hispanic voters are not identified as a separate category.

4 COVI ranges from -2.78 (lowest burden associated with voting) to 1.77 (highest burden associated with voting). The standard deviation of COVI is 0.68.rate. For Black voters, a one-point increase in COVI is associated with a 0.3 percentage point decrease in voter turnout rate. For Asian voters, however, the relationship is not statistically significant, meaning that it cannot be concluded by this model alone that there is a relationship between the cost of voting and voter turnout rate for Asian voters.

Author

Amelia Minkin received a Master of Public Policy from Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy in May 2024 and holds a B.S. and a B.A. from the University of Florida. She is a research associate at Issue One and a Data Science fellow at Decision Desk HQ. Amelia is passionate about the intersection between data science and elections and focuses on domestic issues related to election administration, voting rights, and democracy.