Abstract

In response to security threats in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the U.S. Capitol was made less accessible to the public through a series of security upgrades, including an expansion of the Capitol Police force, new visitor registration programs, and the construction and implementation of physical barriers in and around the Capitol building. However, increased safety for members and staff has had consequences for the Capitol building’s important symbolic representation. Previous inquiries into the design and use of capital cities have revealed that these places are symbolically important as embodiments of public values. In this article, the authors argue that by repeatedly prioritizing public displays of security over public access, Congress has inadvertently contributed to the alienation Americans feel from their government, with implications for January 6th and beyond.

We have built no national temples but the Capitol; we consult no common oracle but the Constitution.

—Representative Rufus Choate, 1833

Previous studies and observer reflections have identified the U.S. Capitol building as both the physical embodiment of the Republic, a place in which representatives from geographic subdivisions within every state come together to debate public policy issues and make national laws, and as the symbolic representation of democracy itself. Examples abound: The Library of Congress’s online exhibit about the Capitol building describes it as a “temple of liberty,”[1] as does historian Pamela Scott (1995) in her book of the same name. Mueller et al. (2017) wrote, “The U.S. Capitol Dome is one of the most recognizable structures in the world and stands as a symbol of democracy” (p. 46). On May 14, 2021, Speaker of the U.S House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi wrote to her Democratic Party colleagues, “The Capitol of the United States has always been a welcoming beacon of democracy for the American people and to the world.”[2] The website of the Architect of the Capitol (n.d.), whose office is charged with the preservation and upkeep of the Capitol and its surrounding environment, describes the building as “a monument not only to its builders but also to the American people and their government” (para. 3).

The notion of the Capitol building as both the physical and symbolic locus of American democracy exists for good reason. Pierre L’Enfant’s plan for the City of Washington, whether by design (Young, 1966) or by happenstance (Berg, 2007), enshrined the major principles of the U.S. Constitution—specifically federalism and separation of powers—in the design of the nation’s capital, with the Capitol building occupying the highest point in the city. As Berg (2007), wrote, “In L’Enfant’s plan the home of Congress took center stage” (p. 112), just as the Constitution’s framers intended Congress to be the first branch of government.

Much has been written about the Capitol as both a physical and symbolic embodiment of American democratic principles. The ways the building has been physically changed over time to accommodate a growing nation have also been well documented (e.g., Allen, 2005). Some recent scholarship has begun telling the story of the anti-democratic elements (Goldman-Petri, 2021) of the Capitol’s foreboding architecture and how the construction and adornment of the building depended nearly entirely on the labor of enslaved people (Monteiro, 2020). These accounts make clear that the design, construction, expansion, and work within the Capitol have always reflected the sociopolitical circumstances in the United States at large.

Thus, it is surprising that little attention has been given to how changes to the Capitol’s security apparatus over the last quarter century have shaped the public’s orientation to its most visible and public symbol of democracy and to the work that occurs within it. This is true even as scholars in fields as diverse as architecture, philosophy, history, and sociology have considered how both physical structures and the domestic security state can affect individuals’ orientations toward government and toward one another (Geenens & Tinnevelt, 2009). The Capitol building has been given short shrift, too, in analyses of the impact of enhanced security throughout the nation’s capital more broadly, which have tended to focus on the geographic area closest to the White House. For example, in her study of the National Mall, Benton-Short (2007 noted that “the nation’s capital has become a fortress city peppered with bollards, bunkers, and barriers” (p. 433), and Hoffman et al. (2002) derided the closure of Pennsylvania Avenue in the mid-1990s as being “at odds with the core values of an open and democratic society” (p. 43). Yet, there has been little academic discussion of the impact of an increasingly militarized and securitized Capitol complex on the ability of citizens to engage in the work of democracy or on the capacity of Congress to serve the function of connecting citizens to their government.

In this article, we discuss the ways the physical space and symbolic meaning of the U.S. Capitol have changed as a consequence of an increased focus on security, and consider how these changes may have contributed to the events of January 6, 2021. Ramped up security at the Capitol—which began in earnest in 1998 after two U.S. Capitol Police officers were killed by a mentally ill gunman who opened fire at a security checkpoint and made his way into the corridor housing the Majority Whip’s office suite—has intended to prevent incursions into the building and, by extension, to protect the building, those who work within it, and even democracy itself from harm. Here, however, we suggest the possibility that these changes have further contributed to putting “government at a distance and out of sight” (Young, 1996, p. 13) from the public that the institution is intended to serve. Using theories of democratic space as the foundation of our analysis, we chronicle the changes over time to the Capitol security apparatus, consider the ways a more secure Capitol is also a less democratic space, and discuss the implications both for the January 6, 2021, insurrection and for restoring the public’s sense of political efficacy and civic community.

The Concept of Democratic Space

Although political theorists have long considered issues of space and place, policy scholars have largely avoided wading into normative questions about the connection between space and political outcomes. John Parkinson, a British political theorist and policy scholar, is an exception. His recent work has considered the importance of public space and the implications of trading openness for elite safety. As Parkinson (2009a) noted,

Issues of public space in general matter for many reasons: it is important for people to have space in which to interact with their elected representatives, for one, and the present climate in which security concerns override almost all other values has seen a significant decrease in the accessibility of public space and public officials. (p. 5)

However, what constitutes public space has been contested. Goodsell (2003) identified three primary disciplinary sources of the divergent meanings of the concept of public space: political and moral philosophers, urban planners, and architectural analysts. Political philosophers and democratic theorists, following Arendt (1958) and Habermas (1989), have conceptualized public space (often described as the “public sphere”) as a social realm for essential public discourse, the threats to which are the primary focus of their analyses. More recently, scholars have considered the democratic potential of internet space and the ways the architecture, boundaries, rules, and processes of online communities enhance and inhibit opportunities for democratic discourse (Forrestal, 2017). The potential consequences of technology for public space are significant enough that some scholars have gone so far as to advocate a “farewell to the old model of a monumental public space” (Hénaff & Strong, 2001, p. 230). By contrast, urban planners often speak of physical (i.e., non-metaphoric) public space, usually referring to urban sites intended for public use and for the development of interpersonal connection and opportunity for expression. For these scholars, the transformation of traditional public spaces into commercial and privately owned gathering sites, such as shopping malls, threatens the capacity of these spaces to perform their social function, one that cannot be simply moved online without deleterious effects. For architectural interpreters, the unit of analysis is, most frequently, specific buildings, usually explicitly identified with the state. These scholars pay particular attention to how the building or structure they are studying “expresses historical or regime values, affects the conduct of contemporary users, and projects images for consumption by passing viewers” (Goodsell, 2003, pp. 367–368). Although these bodies of literature glance off one another occasionally, we find that there has been little integration of their different approaches and little attention to the concerns they have raised.

Seeking to provide a unified definition of public space, Parkinson (2013) focused on the ways a space can be public, identifying three nonexclusive possibilities: Space can be openly accessible; it can be a space of common concern, either through use of resources or effects; or it can be used for “performing public, political roles” (p. 440). This third category perhaps best describes the U.S. Capitol, within which legislators perform their essential democratic roles through the making of claims and decisions, the representation of multiple perspectives, and debate and deliberation about matters of common concern. However, these acts alone do not per se make the Capitol or other legislatures democratic spaces; insofar as they occur in the absence of attentive publics, a fundamental democratic element is unfulfilled. Thus, democratic space requires both the performance of these public roles and access to that performance by the nonperformers (i.e., the nonpoliticians), whose ability to engage with legislators in their work, not merely through symbols, is essential. As Parkinson (2009b) explained, “On this account, public space matters because of the functional necessity of physical arenas for democratic action” (p. 102), among which action is the crucial role of the audience witnessing the making of public claims and collective decisions as well as observing the decision makers (p. 111). Thus, democratic space requires not only the presence of the audience, but also “an encouragement of access, a muting of authority, a minimization of barriers, unofficial as well as official staging, and an attempt to create conditions favorable to deliberation” (Goodsell, 2003, p. 22)

The Capitol Security Apparatus: Then and Now

Democratic space inside the legislature thus requires both the opportunity for such an audience to fulfill its role in the performance of democracy as well as meaningful access to the building, galleries, and committee rooms where the work of legislating—and democracy—occurs. Put more succinctly, in order for public spaces to be democratic spaces, they must be open and accessible to the people. The ability of the public to access the Capitol building and the national legislature it houses is the root of the building’s symbolic power. As Strand and Lang (2013) wrote, “Congress has traditionally been the branch of government nearest to the people, and the building has been relatively open to reflect that.” Yet, when the public space in question is also the forum for the creation of law, as is the case with the U.S. Capitol complex, questions of access are inextricably intertwined with perceptions of influence. Thus, when the Capitol building and the U.S. Congress are inaccessible to the public, there are consequences both for public perception of the representative nature of government and for the actual practice of representation. Notably, at the time of this writing, in September 2021, the U.S. Capitol has been closed to visitors for 18 months as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing worries of violence against the building and its members (Mascaro, 2021).

Even when the Capitol is fully open to the public, access is tightly regulated, with visitors subject to scanning, searches, and limitations on items that can be carried into the building (U.S. Capitol Visitors Center, n.d.). This has been true at least since 1998, in the aftermath of the killing of the two U.S. Capitol Police officers. As Figure 1 reveals, the events of September 11, 2001, accelerated the fortification of the Capitol building; the terrorists who hijacked United Flight 93 almost certainly planned to strike the Capitol’s dome (U.S. Senate, n.d.). As Strand and Lang (2013) explained, “As time has gone on, the institution has added additional security measures in response to attacks and threats.”

Figure 1

A Security Checkpoint at the U.S. Capitol Building Following the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks

Note. Source: CQ Roll Call Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. (Scott J. Ferrell, photographer.) No restrictions on use. Available online at https://www.loc.gov/item/2019645821/.

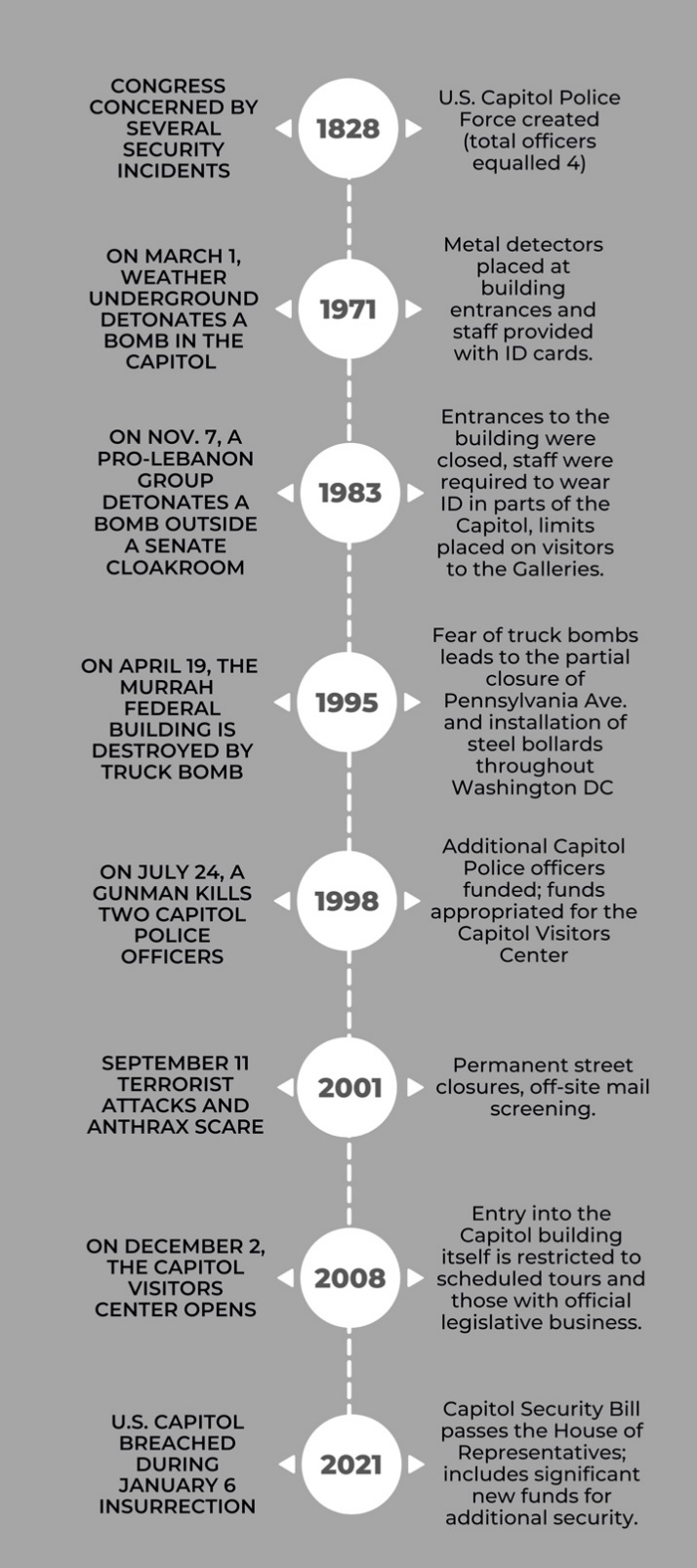

Figure 2 briefly summarizes the major security threats and reactions that have affected the U.S. Capitol building in the last quarter century. Rather than offering an exhaustive list of every incident that has occurred at the Capitol, the figure identifies and briefly describes those events that led to substantive changes in the security measures used to protect the Capitol. Of note, it was not until the early 1970s that entry to the Capitol required undergoing security screening and not until more than a decade later that staff members began to be required to wear identification.

Figure 2

Significant Security Events and Substantive Changes at the U.S. Capitol

Note. Sources: CNN.com (1998), Strand & Lang (2013), Tully-McManiss & McKinless (2018), Grisales (2021), U.S. Capitol Police (n.d.) website.

Perhaps no timeframe was more important to the Capitol’s security apparatus than the period between 1995 and 2001, when in the aftermath of the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, the National Park Service, Secret Service, and U.S. Capitol Police all took steps to limit vehicle access to government buildings and national monuments. As Forgey (2005) wrote,

Make no mistake, it is the possibility of truck bomb attacks such as [Timothy] McVeigh’s [on the Murrah Federal Building], and not other potential terrorist weapons, that is primarily responsible for the concrete barriers, construction fences, and other stuff that today make Washington’s monumental core so ugly and unfriendly. (p. 146)

“Out of Sight and at a Distance”

It has not only been specific security threats that have led to a reduction in access to the Capitol. Architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson (2000) described the “historicization” of the Capitol that began in the 1950s and shifted the building from a “structure capable of extension and remodeling” to “a venerable historical landmark that must be preserved” (p. 139). For Wilson, the effect of this has been to make the work of Congress recede from view. Whether one agrees with Wilson that seeing the Capitol symbolically leads people to have difficulty seeing it as an active workplace, or with Parkinson (2012) that the Capitol becoming a less active workspace has led the public to see it as primarily a historic and symbolic site, the consequences are clear. If “it is easier to think of the building in terms of tourism and less in terms of democratic citizenship [this] makes the securitization of the building easier” (Parkinson, 2012, p. 115).

Security planning inevitably begins with an implicit assessment of both the “what” and “whom” of the threat to be guarded against. While the securitization of the U.S. Capitol (and other federal buildings in Washington, DC) did not start with the Oklahoma City bombing, it did transform that assessment by shifting its focus to be “increasingly directed at American citizens” (Upton, 2021). The implications of the resulting “landscape of fear” extend far beyond aesthetic objections to Jersey barriers or concerns about convenience. Rather, the reconfiguration of the nation’s capital city and its Capitol building has effectively situated the citizenry as a threat to the democratic process rather than as the collective on whose behalf it operates and whose active presence is essential to its operation.

Take, for example, the process of entering the U.S. Capitol as a visitor in the years prior to 2008. Although bag checks and magnetometers were present at every door, one had many options for entering the building, including the possibility of climbing the west steps to “an entrance once carefully designed to convey that this monument to democracy was indeed open and accessible to all” (Vale, 2005, p. 41). If the House or the Senate were in session and one wanted to observe the proceedings, they would seek a Gallery pass from their representative or senator, or from the visitor’s desk located on the first floor of the building and follow signage to the entrances to the galleries.

Today, however, “a visitor’s experience of the building starts not with the debating chambers, but with an exhibition and things to consume. It is a tourism experience” (Parkinson, 2013, p. 445). Entrance to the building is severely restricted. Visitors enter underground below the east front plaza, far from the building’s intended portal. They check all backpacks, large bags, and metal jewelry, submit to a scan of all remaining items, queue to obtain the required sticker needed for entry, then queue again to wait to be admitted to see the required video presentation. If visitors are too early to line up for their assigned admission time, the Visitor Center’s website instructs them to “begin [their] Capitol experience … by visiting our temporary exhibits, perusing our Gift Shops or dining in our Restaurant.”[3] Following the video presentation, visitors are handed headsets and are asked to choose one of five queues, each of which becomes a tour group so large that the headsets are required to be worn in order to ensure that the guide can be heard. Tours are restricted to the historic areas such as the Crypt, the Old Supreme Court chamber, the Rotunda, and National Statuary Hall. Visiting either the House or Senate Gallery still requires obtaining separate passes, but now those passes must be obtained through request to one’s representative or senator. The Gallery pass itself admits visitors to view floor proceedings but only after they submit again to supplemental security measures and check all cameras, phones, and other recording devices. Visitors are then reminded of the strict rules of behavior expected while in the Gallery, which include not talking, reacting to speeches or votes, or otherwise making sounds that could be disruptive to the business taking place below. Thus, “acting as a public citizen in a public gallery is dealt with severely … with the lower status cues reinforced by the strict access and behaviour controls enforced by guards, physical barriers, more subtle design elements, or all three” (Parkinson, 2013, p. 446).

Tourists, by definition, are guests, visitors whose continued presence is contingent on their compliance with the rules of the sites they visit. Casting the Capitol as first and foremost a site for tourists (e.g., restricting access by requiring tickets, entry through a single, highly controlled portal), means that citizens wishing to observe and engage the work of legislating are reminded that they are only contingently present, without any right to presence or participation. This tourist model of access privileges individuals acting as consumers over “purposive publics—people and groups of people with certain kinds of public purposes” (Parkinson, 2013, p. 447), thus subordinating the democratic values of accessibility, participation, and accountability to that of security. Importantly, by casting the Capitol as a monument and historical site rather than as a functioning representative forum, it has become possible to inhibit, if not outright prevent, citizens from engaging in essential democratic functions in that space.

Of course, while unfettered access to legislators and legislative proceedings is impractical if the work of Congress is to occur, the significant barriers to the presence and participation of those being represented signal that the work occurring in the “people’s branch” is best accomplished with those people kept at a distance. Revealingly, at a September 10, 2002, hearing on post-9/11 security, Representative Steny Hoyer acknowledged that the post-9/11 security measures rendered the Capitol “a little less open, a little less hospitable to those who own this Capitol” but added that these measures were necessary to “protect the people who come to this building to participate in democracy here in their Capitol” (House Committee on Administration, 2002). Implied in Representative Hoyer’s statement is the notion that only certain credentialed participants are deserving of full access rights to the building: representatives and senators, staff members, lobbyists, and the media. Implicit as well in Hoyer’s observation is the idea that restricting rank-and-file members of the public from entering the Capitol is somehow not a restriction on public participation in the democratic process. Hoyer’s sentiments support Vale’s (2005) conclusion that, “all too often, ‘securing public space’ means securing space from the public, rather than for it” (p. 41).

Conclusion

Nearly a half century ago, Marcus Raskin (1976) argued that the U.S. national security state is inimical to the rule of law because it sets up national security agencies in opposition to citizens. A similar dynamic is at work here. Having relegated the public to outsider status in the lawmaking process and having imposed stringent security measures to ensure that the public cannot do harm to those who are entitled to be in the Capitol building, Capitol complex security measures have ensured that Congress and the public are both literally and metaphorically opposed to one another. After all, “national symbols are constructed by patterns of use and habit as much as deliberate association” (Parkinson, 2012, p. 195). Therefore, it becomes all the more essential to consider those patterns of use and habit and the purposes they serve.

To the degree that the securitization of the Capitol has meaningfully increased actual security of the complex, one might consider the trade-off between preserving democratic space and protecting the building and the people within it worth the cost. However, it is profoundly unclear that the ever-more-severe ratcheting up of security measures has, in fact, resulted in greater safety. On the contrary, many of these measures appear to be “security theater,” a term coined by Bruce Schneier (2009) to describe “the security measures that make people feel more secure without doing anything to actually improve their security.” Yet, this description implies that security theater is essentially benign, neither contributing to security, nor causing harm. If, however, the security measures taken are more than falsely reassuring, if they are both reflective and constructive of a legislature and a public deeply alienated from one another, the effects are far more significant. Consider, for example, the Task Force 1-6 Capitol Security Review (U.S. Speaker, 2021) commissioned by Nancy Pelosi. The report recommends more than 850 additions to the Capitol Police force (which is already larger than the municipal police departments in Atlanta, St. Louis, New Orleans, or Denver), the re-establishment of a mounted unit and increased numbers of explosive detecting dogs, the creation of dedicated Civil Disturbance Units to surveil and respond to First Amendment-related activities, additional screening vestibules for the north and south entrances, and a “hardening” (p. 10) of all Capitol entrances.

The implications of this are bleak. There is no indication that the events of January 6th are likely to spur a reckoning about the ways a more open and accessible Capitol building would encourage more constructively engaged and appropriate civic participation. On the contrary, “each incident, then, justifies an increase in the control of public use of ostensibly public spaces” (Upton, 2021). Indeed, in a January 26, 2021, House hearing on the storming of the Capitol, Yogananda D. Pittman, the acting head of the Capitol Police, told representatives,

I do not believe there was any preparations that would have allowed for an open campus in which lawful protesters could exercise their First Amendment right to free speech and at the same time prevented the attack on Capitol grounds that day. (as cited in Upton, 2021)

She argued instead that “to prevent a similar incursion in the future, lawmakers will have to sacrifice public access to the building to bolster security measures.” Yet, as it sacrifices public access to the Capitol in the name of security, Congress must begin to take seriously the possibility that the profound alienation such measures engender is as much a threat to the practice of democracy as the attacks they seek to prevent.

References

Allen, W. C. (2005). History of the United States Capitol: A chronicle of design, construction, and politics. University Press of the Pacific.

Architect of the Capitol. (n.d.). U.S. Capitol building. https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/capitol-building

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

Benton-Short, L. (2007). Bollards, bunkers, and barriers: Securing the National Mall in Washington, DC. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25, 424-46.

Berg, S. W. (2007). Grand avenues: The story of the French visionary who designed Washington, DC. Pantheon Books.

CNN.com. (1998, July 24). Security measures could not stop Capitol Hill shooting. https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/07/24/security.shooting/

Forgey, B. (2005). The force of fear. Landscape Architecture Magazine, 95(7), 148, 146–147.

Forrestal, J. (2017). The architecture of political spaces: Trolls, digital media, and Deweyan democracy. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 149–161.

Goldman-Petri, M. (2021, February 16). Is the U.S. Capitol a “temple of democracy”? Its authoritarian architecture suggests otherwise. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/is-the-us-capitol-a-temple-of-democracy-its-authoritarian-architecture-suggests-otherwise-154144

Geenens, R. & Tinnevelt, R. (Eds.) (2009). Does truth matter? Democracy and public space. Springer.

Goodsell, C. (2003). The concept of public space and its democratic manifestations. Journal of Public Administration, 33(4), 361–383.

Grisales, C. (2021, May 20). From trauma counselors to fencing, what’s in the House-passed Capitol Security Bill. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/05/20/998535467/from-trauma-counselors-to-fencing-whats-in-the-house-passed-capitol-security-bil.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT Press.

Hénaff, M., & Strong, T. (Eds.). (2001). Public space and democracy. University of Minnesota Press.

Hoffman, B., Chalk, P., Liston, T. E., & Brannan, D. W. (2002). Security in the nation’s capital and the closure of Pennsylvania Avenue: An assessment. RAND. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2005/MR1293-1.pdf

House Committee on Administration. (2002, September 10). Opening remarks of Representative Steny Hoyer. Hearing on security updates since September 11, 2001. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107hhrg82351/html/CHRG-107hhrg82351.htm

Mascaro, L. (2021). Closed U.S. Capitol is a somber backdrop this July 4. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-07-03/closed-us-capitol-july-4-independence-day-insurrection-pandemic

Monteiro, L. D. (2020). Power structures: White columns, white marble, white supremacy. Medium.com. https://intersectionist.medium.com/american-power-structures-white-columns-white-marble-white-supremacy-d43aa091b5f9

Mueller, P., Abriatis, J., & Kieffer, J. (2017). The art of restoration: Saving the U.S. Capitol dome. The Military Engineer, 109(710), 46–50.

Parkinson, J. R. (2009a). Symbolic representation in public space: Capital cities, presence and memory. Representation, 45(1), 1–14.

Parkinson, J. R. (2009b). Does democracy require physical public space. In R. Geenens & R. Tinnevelt (Eds.), Does truth matter: Democracy and public space (pp.101–114). Springer.

Parkinson, J. R. (2012). Democracy and public space: The physical sites of democratic performance. Oxford University Press.

Parkinson, J. R. (2013). How legislatures work—and should work—as public space. Democratization, 20(3), 438–455.

Pelosi, N. (2021). Dear colleague on returning the Capitol to a safe and secure temple of democracy. https://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/51421-2

Raskin, M. (1976). Democracy versus the national security state. Law and Contemporary Problems, 40(3), 189–220. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/lcp/vol40/iss3/7

Schneier, B. (2009). Beyond security theater. New Internationalist. https://www.schneier.com/essays/archives/2009/11/beyond_security_thea.html

Scott, P. (1995). Temple of liberty: Building the Capitol for a new nation. Oxford University Press.

Strand, M., & Lang, T. (2013). Protecting the Congress: A look at Capitol Hill security. https://www.congressionalinstitute.org/2013/09/27/protecting-the-congress-a-look-at-capitol-hill-security/

Tully-McManus, K., & McKinless, T. (2018, July 24). Shooting of Capitol Police officers was turning point for department. Roll Call. https://www.rollcall.com/2018/07/24/shooting-of-capitol-police-officers-was-turning-point-for-department/

U. S. Capitol Police. (n.d.). Our history. https://www.uscp.gov/the-department/our-history

U.S. Capitol Visitors Center. (n.d.). Prohibited items. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/plan-visit/prohibited-items

U. S. Senate. (n.d.). The Capitol building as a target: September 11, 2001. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Attack.htm

U.S. Speaker of the House. (2021). Task Force 1-6 Capitol security review. https://www.speaker.gov/sites/speaker.house.gov/files/20210315_Final_Report_Task_Force_1.6_Capitol_Security_Review_SHORT.pdf

Upton, D. (2021, February 8). The fortification of Washington, or, two weeks in the red zone. Platform. https://www.platformspace.net/home/the-fortification-of-washington-or-two-weeks-in-the-red-zone

Vale, L. (2005). Securing public space. Places, 17(3), 38–43.

Wilson, R. G. (2000). The historicization of the U.S. Capitol and the Office of the Architect, 1954–1996. In D. R. Kennon (Ed.), The United States Capitol: Designing and decorating a national icon (pp. 134–168). Ohio University Press/U. S. Capitol Historical Society.

Young, J. S. (1966). The Washington community, 1800–1828. Yale University Press.

Authors

Alisa J. Rosenthal is provost and vice president for academic affairs and professor of political science at Randolph-Macon College. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science and history from Beloit College and Master of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in political science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Dr. Rosenthal joined the Randolph-Macon College community in 2019, following 15 years as a faculty leader and administrator at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, Minnesota. As a political scientist, Dr. Rosenthal specializes in constitutional law and political theory. She was the recipient of the College’s Edgar M. Carlson Award for Excellence in Teaching (selected by faculty) and the Swenson-Bunn Teaching Award (selected by students). In 2016-2017, Dr. Rosenthal served as an American Council on Education Fellow.

Alisa J. Rosenthal is provost and vice president for academic affairs and professor of political science at Randolph-Macon College. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science and history from Beloit College and Master of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in political science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Dr. Rosenthal joined the Randolph-Macon College community in 2019, following 15 years as a faculty leader and administrator at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, Minnesota. As a political scientist, Dr. Rosenthal specializes in constitutional law and political theory. She was the recipient of the College’s Edgar M. Carlson Award for Excellence in Teaching (selected by faculty) and the Swenson-Bunn Teaching Award (selected by students). In 2016-2017, Dr. Rosenthal served as an American Council on Education Fellow.

Lauren C. Bell is professor of political science and dean of academic affairs at Randolph-Macon College. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science from The College of Wooster and Master of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in political science from the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center at The University of Oklahoma. The author or coauthor of five books, including a classroom simulation about the U.S. Congress, Dr. Bell’s solo- and co-authored scholarship has also appeared in The Journal of Politics, Political Research Quarterly, The Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, The Journal of Legislative Studies, and Judicature. She was a 1997–1998 American Political Science Association Congressional Fellow and a 2006–2007 U. S. Supreme Court Fellow.

Lauren C. Bell is professor of political science and dean of academic affairs at Randolph-Macon College. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science from The College of Wooster and Master of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in political science from the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center at The University of Oklahoma. The author or coauthor of five books, including a classroom simulation about the U.S. Congress, Dr. Bell’s solo- and co-authored scholarship has also appeared in The Journal of Politics, Political Research Quarterly, The Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, The Journal of Legislative Studies, and Judicature. She was a 1997–1998 American Political Science Association Congressional Fellow and a 2006–2007 U. S. Supreme Court Fellow.

-

https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/plan-visit ↑