By Ruth Johnson Cronje, Gregory Thomas Nelson, Kali J. Boldt,

Gabrielle Schmidt, Rachel Keniston, and Laurelyn (Weiseman) Sandkamp

Abstract

Political quiescence among low-income Americans is well documented but its causes are not well understood. This study explored the hypothesis that a self-stigmatized identity in low-income individuals is associated with a reluctance to participate in democratic activity. We engaged in participant/observation at nine mealtimes to analyze the discourse of guests of our local community “soup kitchen” and also administered a survey to investigate their perceptions of the poor, their beliefs about causes of poverty, and their knowledge of the demographics of recipients of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. We then offered respondents to the survey the opportunity to sign a petition, write a letter, or both to communicate to their Congressional representatives their position on the question of whether SNAP program funding should be cut. We found that low-income guests with stigmatized attitudes toward the poor were significantly less likely to sign petitions or write letters. We also noted that distancing, embellishment, and embracement were prevalent among the discourse of these guests, all phenomena associated with the struggle to negotiate an identity of value in a stigmatized individual. Our findings suggest that a self-stigmatizing sense of identity is a barrier to participation in civic activity.

Keywords

civic engagement, citizenship, quiescence, stigma, poverty

DOI

10.21768/ejopa.v6i1.130

Author Note

Ruth Johnson Cronje, Rhetoric of Science, Technology, and Culture Program, University Honors Program, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire (UWEC); Gregory Thomas Nelson, UWEC; Gabrielle Schmidt, UWEC; Kali J. Boldt, UWEC; Rachel Keniston, Community Table of Eau Claire; Laurelyn (Weiseman) Sandkamp, UWEC.

Gregory Thomas Nelson, Gabrielle Schmidt, Kali J. Boldt, and Laurelyn (Weiseman) Sandkamp were UWEC undergraduate students at the time of this study and are no longer affiliated with the university.

The authors would like to thank the UWEC Office of Research and Sponsored Programs and UWEC Differential Tuition for their support of this research. The authors also wish to thank their anonymous reviewers, whose careful and thoughtful responses resulted in welcome improvements to this manuscript. This study was conducted with the permission of the UWEC Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research, Federal Wide Assurance Number FWA00001217.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to

Professor Ruth Johnson Cronje

Rhetoric of Science, Technology, and Culture Program

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Centennial Hall 4603

Eau Claire, WI 54702

Phone: (715) 836-5384

Email: cronjerj@uwec.edu

Self-Stigmatizing Identity and Democratic Participation Among Low-Income Individuals

The health of a democracy depends upon the success with which it establishes (or tolerates) conditions that foster full citizen participation, including civic participation among the poor. Opportunities for participation help to create citizens who are more efficacious and astute, and expanding participation into nonparticipating sectors has been shown to lead to more equitable and humane social policies (Gaventa, 1980, 2006b; Hillmer, 2010). However, the same power conditions that perpetuate poverty also limit the democratic participation of people with low incomes (Gaventa, 1980; Reich, 2014; Rosenstone, 1982; Yadama & Menon, 2003). While numerous structural and institutional barriers—including voter ID laws and restricted polling hours—effectively discourage civic participation among the poor, perhaps the most insidious and effective barriers to low-income civic participation are psychological and ideological. Certainly no set of institutional arrangements will foster or enhance power among the poor unless individuals themselves feel a disposition and a sense of capacity to act civically. It is crucial, therefore, to understand those factors that impinge on citizens’ self- perception as viable civic agents. Cerulo (1997) has posited that “scripts of power” colonize minds, thereby initiating and perpetuating stigmas against being poor. Lukes (1974) and Gaventa (1980, 2006a, 2010) have suggested that multiple dimensions of power—visible, hidden, and invisible—influence how people think about their place in the world and shape their beliefs, sense of self, and acceptance of the status quo and can account for democratic quiescence among the poor.

Objective

Our research focused on the problem of civic quiescence among a stigmatized group: low-income guests of a local “soup kitchen” called Community Table of Eau Claire (CTEC). This study investigated the presence of self- stigmatizing attitudes and discourse among these guests and then offered them an observable opportunity to take civic action by signing a petition or writing a letter to congressional representatives. This approach allowed us to investigate whether self-stigmatizing attitudes were associated with civic quiescence in this population.

Methods

Although we did not directly measure the income level of the specific individuals who participated in this study, we chose CTEC as our research site because guests who use this facility as a resource are likely to have incomes low enough to cast them into food insecurity (see Appendix A).

Given that we were interested in exploring complex human behavior and attitudes in response to a specific set of conditions and circumstances, we used mixed methods for this study. Our pragmatic approach (Cresswell, 2003) focused on actions of CTEC guests in response to a specific situation–that is, an opportunity to engage in low-cost democratic participation—to explore the problem of civic quiescence among low-income individuals. Responses to items from validated surveys of guests’ beliefs about causes of poverty and attitudes toward the poor (Atherton, 1993; Barrientos & Neff, 2011; Bullock, 1999, Cozzarelli, 2001) provided quantitative data we could test statistically for attitudinal differences between civically quiescent guests (“nonactors”) and those willing to take democratic action (“actors”). To form a more nuanced picture of the possible presence of self-stigma among CTEC guests, we augmented the survey by observing guests’ mealtime conversations, which offered opportunities for them to interact with and talk about other low-income individuals. We analyzed these qualitative data to “surface” ways that guests might have been struggling to negotiate an identity of value as members of a stigmatized social group (Boydell et al., 2000; Dorey, 2010; Ruetter et al., 2009; Snow & Anderson, 1987). By mixing concurrent qualitative and quantitative data, we hoped to compensate for the limitations of a convenience sample and go beyond the prestructured survey format to pursue a wider range of possible reasons for guests’ decisions to forego or seize a low-cost opportunity to participate in democracy.

Survey and Civic Invitation

Three of the authors created a survey to investigate beliefs about the causes of poverty, attitudes about the poor, and self-reported voting behavior among CTEC guests (see Appendix B). Items assessing attitudes and beliefs were obtained from previous studies (Atherton, 1993; Barrientos & Neff, 2011; Bullock, 1999; Cozzarelli, 2001). We used Likert-type response arrays for most survey items; however, we integrated one forced-choice item and one item providing an array of adjectives to describe low-income people, and asked guests to circle those adjectives they thought represented “the vast majority of people collecting Food Share benefits.” Before we administered the survey at CTEC, we pilot tested the instrument with 12 undergraduate students to ensure the comprehensibility of item wording and the appropriateness of response arrays.

We administered this survey to any willing guest eating a meal at CTEC during two mealtimes (i.e., dinner on November 22, 2013, and lunch on December 18, 2013), a period during which the United States Congress was engaged in debates about whether to cut funding to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (distributed in Wisconsin as Food Share) as part of its overhaul of the federal Farm Bill. A convenience sample of nearly all guests who attended the mealtimes on these two collection dates were recruited to take the survey; only guests who finished their meals too quickly to be recruited were not approached. Guests were offered the option of completing the survey on paper or having the survey verbally read to them. Six guests opted for assistance, and we recorded their responses onto blank survey forms.

After taking the survey, each guest was invited to take civic action. Under a large banner reading “Food Stamp Cuts: Tell Congress What You Think,” we set up tables where guests could sign petitions to each of the district’s three federal congressional representatives; one petition expressed support for the SNAP budget cuts while the other expressed opposition, so that guests had the opportunity to sign a petition regardless of their position on this issue. In addition, we provided stationary and envelopes pre-addressed to each of the three congressional representatives so that guests could write letters if they wished. Additional materials present in the room included photographs (downloaded from their official websites) of all three representatives, with a caption noting each representative’s official stance on the SNAP budget issue, as well as a poster with some general, nonpartisan, “boilerplate” language that guests could integrate into their letters if they wished. Guests sealed their own letters and were then given the choice of either giving them to us to mail or taking them home to mail themselves. Investigators made no attempt to read any of the guests’ letters; however, several guests requested help in writing their letters, and one guest asked us to read the letter she had written and to tell her whether we thought it would be effective—requests to which we acquiesced.

Quantitative analysis of survey data. In focusing on the issue of democratic quiescence among low-income CTEC guests, we divided survey respondents into two subgroups: Respondents were coded as “actors” if they signed at least one of the petitions, wrote at least one letter, or did both; all others were considered “nonactors.” Responses for each Likert-type item were averaged within actor and nonactor groupings, and a student’s t-test was used to determine whether differences between these groups were significant. Adjectives included in the item that asked respondents to circle descriptors of “the vast majority of Food Share

recipients” (see Appendix B, Question 10) were chosen to be clearly value-loaded, ranging from positive to negative descriptors. A generalized linear model with a binomial error distribution was constructed to determine if willingness to take civic action could be predicted by the selection of these descriptors. An ANOVA was then used to test for the power of specific adjectives in predicting guests’ willingness to take civic action. Responses to the forced-choice question (see Appendix B, Question 12) were analyzed with a Pearson’s Chi-square test. All statistics were calculated using R version 3.2.1 (http://www.R-project.org) and the generalized linear model was implemented using the R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015).

Participant Observation

Two of the authors visited CTEC nine times over the course of four months (i.e., November 2013 to February 2014). These visits included both afternoon and evening meals. Two of these nine instances were concurrent with our collection of survey data and our invitation to participate in letter-writing and petition-signing activity. During each visit, we received and ate the free meal offered. We used no standardized protocol to determine where we would sit at any given mealtime; instead, we chose tables where guests were already seated and talking amongst themselves, and where there was a free seat to accommodate us. Throughout the course of each meal, we listened to and, as appropriate, participated in the conversations that occurred naturally. We avoided “seeding” conversations; rather, we responded to conversational topics other guests initiated with us and at times initiated related conversational topics, as would be normal in any public mealtime conversation.

Since it was important to observe normal mealtime conversation, we did not record conversations or take notes at the table. Immediately after each visit, we moved to another location where we independently recorded all statements and conversation we could remember to the best of our ability. During the first two visits to CTEC, we both ate at the same table so we could listen and contribute to the same conversation; this permitted us to verify our respective independent memories of the conversations that had occurred during those meals and to standardize recollection notes. All other mealtimes were observed independently to increase the number of conversations we were able to witness and participate in.

Qualitative analysis of participant-observation data. We used Dedoose version 6.1.18 software (http://www.dedoose.com) to archive and independently code the conversational notes and discourse captured in the participant-observation sessions. Codes were a priori derived from Snow and Anderson (1987), but additional codes were later added as we noted discourse types not captured by Snow and Anderson’s typology. We used the Dedoose “pilot test” function to calculate Cohen’s Kappa, achieving an interrater agreement of 0.85 (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Results

We collected 74 survey responses; however, one survey was removed from the dataset because the respondent had circled “neither agree nor disagree” for every item. Therefore, we analyzed a total of 73 surveys. Of these 73 respondents, 27 (37%) chose to sign the petition, and 21 (29%) chose to both sign the petitions and write a letter (all letter writers also signed a petition). Thus, we coded a total of 48 survey respondents (66%) as civic “actors.” Twenty-five respondents (34%) completed surveys but did not sign a petition or write a letter, and thus were coded as “nonactors.” No actor chose to sign the pre-prepared petition expressing support of the SNAP cuts; all petition signers chose the petition expressing opposition to the cuts.

Many guests self-reported as having voted in at least one state or federal election within the past five years, with more than half (56%) reporting they voted in the most recent presidential election.

Although our results indicated the presence of some self-stigmatizing beliefs among both the actors and the nonactors (see Table 1), for eight of the 13 Likert-type opinion items, nonactors were significantly more likely to express attitudes consistent with stigmatized beliefs about the poor. Nonactors were significantly more likely to agree that food stamps make people lazy (P = .01), that the government spends too much money on poverty programs (P = .02), that too many people on Food Share spend their money on drinking and drugs (P = .02), and that many women getting Food Share are having illegitimate babies to increase the money they get (P = .02). In contrast, actors were significantly more likely to agree that Food Share recipients should be able to spend their money as they choose (P = .03), that poor people generally use Food Share wisely (P < .01), and that the U.S. government is spending too little money on federal food assistance programs (P = .05). Actors were also more likely to agree that people are often ashamed of being on Food Share (P = .02).

| Item | Actors | Non- Actors | P value |

| Food stamps make people lazy | 6.2% | 4.0% | .01 |

| Food stamp recipients should be able to spend their money as they choose | 75.0% | 52.0% | .03 |

| An able-bodied person using food stamps is ripping off the system | 12.5% | 16.0% | .18 |

| Society has a responsibility to help poor people | 79.2% | 68.0% | .56 |

| People on food stamps should be made to work for their benefits | 20.8% | 28.0% | .09 |

| Out-of-work people ought to have to take the first job that is offered | 18.8% | 36.0% | .09 |

| The government spends too much money on poverty programs | 4.2% | 16.0% | .02 |

| Poor people generally use food stamps wisely | 72.9% | 40.0% | .008 |

| Poor people have a different set of values than do middle-income people | 47.9% | 52.0% | .98 |

| Most poor people in this country have a chance of escaping from poverty | 35.4% | 44.0% | .51 |

| Generally speaking, we are spending too little money on food stamp programs | 70.8% | 48.0% | .04 |

| People are often ashamed of being on food stamps | 66.7% | 52.0% | .02 |

| Too many people on food stamps spend their money on drinking and drugs | 10.4% | 20.0% | .02 |

| Many women on food stamps are having illegitimate babies to increase the money they get | 20.8% | 36.0% | .015 |

Table 1: Comparison of Survey Responses by Actors and Non-Actors at the Community Table of Eau Claire

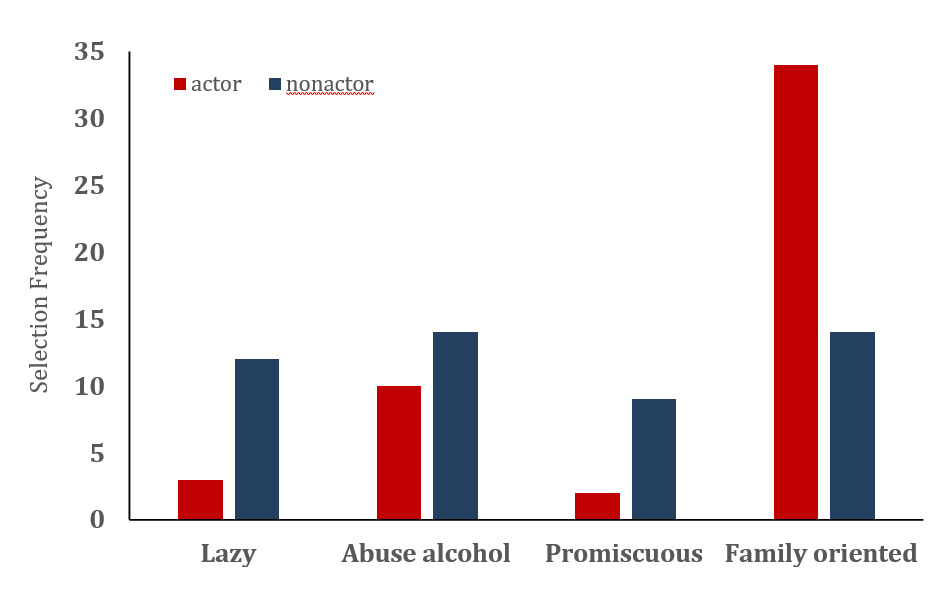

The association between self-stigmatization and unwillingness to take civic action was further corroborated by responses to the adjective-circling item. Our logistic regression model explained 40% of the variation of the data (P < .01). The circling of the descriptors “lazy,” “abuse alcohol,” and “promiscuous” were significant predictors of a respondent being a nonactor (P = .002, .001, .03 respectively), while circling the descriptor “family-oriented” was a significant predictor of a respondent being an actor (P = .03) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The majority of people receiving Food Share have which attributes? Only descriptors that were important for predicting actor outcomes are shown.

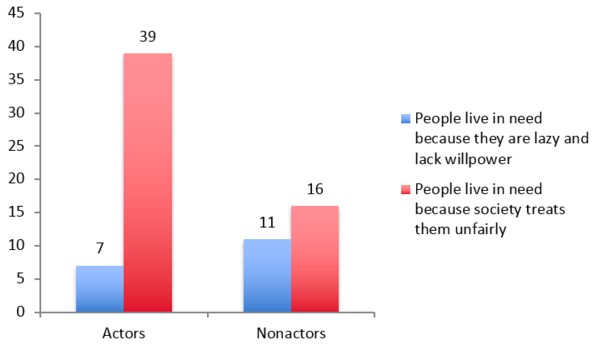

Additionally, differentials in participants’ willingness to take civic action reflected differences in beliefs about the causes of poverty in the United States. Individuals who indicated that they believed people live in need “because society treats them unfairly” were significantly more likely (P = .03) to take civic action than those who believed people live in need “because of laziness or lack of willpower” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Why do people live in need? Number of actor responses versus number of nonactor responses (n = 73).

During the five evening and four lunchtime visits, we noted 105 conversation excerpts among guests at CTEC that were used either to construct identity or to express other important values (see Table 2). We adopted three of the “identity work” discourse code categories created by Snow and Anderson (1987): distancing, embellishment, and embracement were commonly found in these mealtime conversations. Additionally, three new discourse types emerged from the discourse which we deemed to be related to identity construction: machismo, “fightin’ words,” low-income life practice.

| Code Name Code Description | Times

Observed |

|

| Distancing* | Talk that distances the speaker from other low-income individuals, low-income “roles,” and from institutions serving low- income individuals | 32 |

| Embracement* | Verbal and expressive confirmation of one’s acceptance of and attachment to a social identity associated with a general or specific role, a set of social relationships, or a particular ideology | 14 |

| Embellishment* | Narration of stories about one’s past, present, or future experiences or accomplishments that have a fictive character from exaggerations and fanciful claims to fabrications | 10 |

| Fightin’ words | Talk that expressed the speaker’s opinion that the current situation/conditions called for civic action | 4 |

| Machismo | Talk that expressed the “toughness” of the speaker and his/her resilience in dealing with difficult situations and events | 4 |

| Low-income life practice | Talk that articulated “hints” or activity that helped the speaker survive or get along on a low income | 18 |

| Other identity | Talk that appeared to be doing “identity work” but could not be categorized under identity categories derived from Snow and Anderson (1987) nor those created for this study | 5 |

| Other values | Talk that expressed important values held 17 by the speaker but that did not appear to be doing “identity work” | 17 |

Table 2: Types and Frequencies of Discourse Observed by Participant-Observers at the Community Table of Eau Claire at Nine Mealtimes

* Adopted from Snow and Anderson (1987)

The most common type of identity discourse we observed was distancing discourse. Associational distancing, which “removes” the speaker from identity affiliation with stigmatized others, was exemplified by remarks such as the following:

- These kids who are on the street, they keep coming here year after year, they’re on the street because they want to be.

- A***** had better shape up or she’s going to lose those kids. Getting drunk all the time; if Social Services hears about that…

We also observed instances of associational embracement, in which speakers declare their affiliation with and social relationship to other guests. For example, one guest, a “regular” at CTEC, announced that she called herself “Mom” and was called “Mom” by several of the much younger guests, only one of whom was her biological daughter.

Embracement of Christian ideology was another of the more common types of embracement discourse we observed. For example, one guest standing in line to receive her meal wore a tee shirt that read, “I’m the Christian the devil warned you about.” Several of our mealtime conversations involved guests asking questions about our religious beliefs and proselytizing to recruit us to participate in faith activity: “Where do you have Jesus in your life? … I’ve lost Jesus for long times in my life. But he’s always there for you if you look to him.”

Discourse we coded as machismo and embellishment frequently co- occurred, as did embellishment and low-income life practice discourse. Talk about low-income life practice often described activities that guests may have been forced into by their income situation. One male guest stated that although he had dislocated his shoulder, broken his hand, and had bone-deep lacerations in his arm, he had not

received medical attention due to lack of funds and sought instead to treat himself. He did so by re-setting his own shoulder and making a splint and super-gluing his wounds together to allow them to heal. When a fellow guest inquired about infections, the younger man stated he had a strong immune system and had never been “truly infected.” He indicated he did not like taking drugs and could “handle pain.”

One type of discourse that particularly interested us was talk that we coded as “fightin’ words”—discourse that expressed political opinions or seemed to comprise a call to civic action. For example, on one of the evenings when we were collecting survey data and offering guests the opportunity to sign petitions and write letters, an individual came into the room where we had set up the letter/petition stations and remarked, “It’s about time we went elephant hunting!”, accompanying this remark with a gun-shooting hand gesture. Another guest entered the room, saying:

The people running the government had better watch out. People will only put up with this shit for so long. Eventually there’s going to be rioting in the streets, and the people trying to cut these benefits are going to get hurt.

Discussion

While by no means univocal, responses to the survey clearly indicated the presence of self-stigmatizing attitudes among some of the CTEC guests, just as Bullock (1999) noted in her surveys of low-income individuals. Furthermore, among the CTEC guests we surveyed, these self-stigmatizing attitudes were associated significantly with a reluctance to participate democratically. Such self- stigmatizing attitudes thus appear to exemplify the “invisible” dimension of power which, Gaventa (1980, 2006a) claimed, suppresses civic activity among the powerless by colonizing their ideologies with a dominant narrative favorable to the power elite. Other research has provided corroborating evidence that power structures can shape a self-stigmatized identity among low-income individuals in ways likely to limit their willingness to act as democratic agents for progressive change on poverty issues (Bullock, 1999; Cozzarelli, 2001; Dorey, 2010; Groskind, 1991; Handler & Hollingsworth, 1969; Horan & Austin, 1974; Mosse, 2007, 2010; Williamson, 1974).

Levine (2015) has grappled directly with the question of why the poor are particularly likely to forego participation in democracy around issues that would redress poverty. He has hypothesized that one reason low-income individuals may not participate in democratic activity is due to the cost of that activity, claiming that perceptions of one’s own financial vulnerability, activated by the “self-undermining rhetoric” prevalent in political calls to action on income-inequality issues, discourage democratic action in situations where money and/or time are limited. Our investigation set up conditions that permitted CTEC guests to take civic action at extremely low cost to themselves in terms of money, logistics, and time (e.g., the table where they could sign petitions and/or write letters was only steps away from where they consumed their meal, and we underwrote the costs of postage for any letter writer requesting it). Our findings suggest that CTEC guests who did not take advantage of this opportunity were doing so for reasons other than their perception of the cost of that civic activity.

Findings from earlier qualitative identity studies using methods comparable to our own corroborate our results among guests of the CTEC. Participant- observation methods similar to those we used enable investigators to study the meaning(s) that people attribute to the situations they confront, including poverty and food insecurity. Since Snow and Anderson’s (1987) work, which uncovered evidence of stigmas against the poor prevalent in the “identity discourse” of the homeless men they observed, other investigators (Boydell et al., 2000; Dorey, 2010; Lott, 2002; Ruetter et al., 2009) have also observed low-income individuals using discourse to psychologically distance themselves from others in poverty. These stigmatizing scripts also reduce their adherence to beliefs in structural causes of poverty, a sense of solidarity with other low-income individuals, and internalized belief in the need for political action (versus individual behavior change) to alter their situation (Boydell et al., 2000; Dorey, 2010; Lott, 2002; Ruetter et al., 2009).

Equally interesting were the CTEC guests in our study who did not express attitudes and beliefs consistent with self-stigmatization. Many guests who took action appeared to resist the dominant narrative and held fast to a structuralist counter-narrative (e.g., that people live in need because society treats them unfairly), suggesting that in this population, Gaventa’s (1980) invisible dimension of civically suppressing power is neither inevitable nor unconquerable. Indeed, guests seemed gratified by the opportunity to take civic action on their own behalf—one thanked us for “giving us a voice,” and we overheard another urge a fellow guest to sign the petition because “this is your chance to tell them what you think.” It is telling that no guest chose to sign a petition supporting the budget cuts to SNAP. All of the guests who chose to sign petitions—even those with self- stigmatizing attitudes—knew where their own best interests lay.

The survey itself, as well as the presence of an onsite opportunity to sign petitions and write letters, represented a situation that undoubtedly evoked an “actor” persona, with its accompanying behavior, in at least some CTEC guests who might not have been thus inclined to act without these spurs. This possibility is supported by the self-reported rates of voting among CTEC guests, which in general are consistently lower than actual voter turnout in Wisconsin as a whole. While self-reported voting rates are innately suspect, the skepticism and political disavowal evoked in some guests by these items—evidenced by those who claimed not to have voted because “my vote doesn’t count”—is consistent with the reduced sense of efficacy that presents a barrier to civic engagement for some Americans. Taylor et al. (2010) have noted that cynicism and fatalism can influence citizens’ sense of civic efficacy and thereby increase their quiescence. However, as Bennett et al. (2013) have observed, this disavowal of the “contaminated sphere” of official politics does not necessarily prevent individuals from being civically engaged— even in such civic capacities as meeting with public officials, lobbying policymakers, etc. Thus, it would be consistent with Bennett et al.’s results for CTEC guests to both represent themselves as alienated nonvoters while also availing themselves of the opportunity to sign petitions and/or write letters.

As Snow and Anderson (1987) and Boydell et al. (2000) have noted, stigmas against poverty pose identity problems that require the poor to struggle to negotiate a valued identity for themselves. Among CTEC guests, the relative prevalence of “distancing” discourse suggests that many of them were concerned with crafting an identity for themselves that differentiated them from other poor people. The associational embracement discourse we noted, particularly that expressing affiliation with religious ideologies, was also consistent with the identity work of individuals struggling to negotiate an identity of value in the face of stigmas. By adhering to a faith-based belief system—a value system with great credibility in U.S. culture—CTEC guests could embrace being part of something that was not stigmatized and that is larger than themselves, feel a sense of self- worth, and thereby negotiate an identity that had more value than the stigmatized identity of “poor person” in much the same ways that the homeless individuals observed by Snow and Anderson (1987) and Boydell et al. (2000) desired lives and identities that were valued.

Guests’ talk about their life experiences provided a fascinating glimpse not only into the strategies they used to negotiate life challenges with limited resources, but also into ways these experiences comprised their “identity work.” The CTEC guest who described his self-treatment of a broken arm to illustrate his “toughness” or resilience may have been attempting to render these painful, dangerous, and frightening experiences into a romantic scenario that disassociated his identity from the vulnerability inherent in being poor. Such “resiliency” discourse was also noted by Montgomery (1994) in the identity work of homeless women. The fairly prevalent low-income life practices discourse we noted in the conversations of CTEC guests—essentially, talk in the form of giving “tips” or describing how they have negotiated getting their needs met in the face of resource constraints—may have represented a persona of competence reinforcing the speaker’s identity as valuable by sharing useful expertise.

Importantly, such discourse may also have functioned to build a sense of “solidarity” with other CTEC guests by articulating a shared experience. Numerous theorists have highlighted the importance of such solidarity in awakening a willingness to enact civic agency (Cerulo, 1997; Gaventa, 1980, 2006b; Hillmer, 2010; Munger, 2002). Cerulo (1997) has claimed that “collective agency includes a conscious sense of group as agent” (p. 393), suggesting that stigmas may promote quiescence by prompting distancing behaviors that diffuse this sense of group agency. Gaventa (2006b) found that building the confidence and self-esteem of excluded groups resulted in greater political inclusion of these groups, which changed development priorities and also the attitudes of public officials and political elites. Gaventa (1980) also noted that Appalachians who were awakened to a sense that their conditions were shared by others were motivated to act in their own behalf (Gaventa, 1980). The situation we created with our survey and petition/letter-writing station may have set up circumstances that spurred CTEC guests to form, however transiently, a collective identity and accompanying sense of civic capacity. Munger (2002) has noted that although identities of competence are more difficult to sustain in the face of stigma, identity can also affect collective agency—the capacity of the poor to act as a group. Binding individuals through discourse creates a shared sense of injustice (Cohen, 1985; Gaventa, 1980; Munger, 2002). The few instances of “fightin’ words” among CTEC guests all occurred at the two mealtimes when we had the petition/letter-writing table set up, suggesting that this particular form of discourse may have been situationally evoked by the presence of an opportunity to take civic action on the SNAP issue.

Limitations

The low-income sector is a demographic comprising individuals with highly diverse life circumstances, values, beliefs, and behaviors. Many of the CTEC guests we surveyed were willing, at least in response to a low-cost opportunity, to participate in civic activity. Others were not. Our findings cannot be generalized beyond the CTEC population present during the period when we administered the survey and offered the civic invitation. Besides being highly diverse, the guests of CTEC are an intrinsically transient population—anyone who walks in the door is offered a free hot meal, no questions asked. Although a subpopulation of CTEC guests are “regulars” who routinely use the facility as a source of food, others visit more sporadically or may never use the resource again. Therefore, even a quota sampling technique could not reliably be said to represent the intrinsically fluid CTEC guest population.

Thus, while the CTEC guests who took our survey or whose conversations we captured in our participant-observation sessions were likely to be low-income enough to be food insecure, our data cannot be taken as representative of a generalized “low-income population” in any community. Indeed, the demographic data collected in this study (see Appendix A) indicated that single males were disproportionately represented among CTEC guests, suggesting that some subsectors of the low-income demographic (e.g., families or women with children) in the study area do not as routinely choose to avail themselves of CTEC as a food source. The data reported here only evidences the existence of certain kinds of beliefs, values, attitudes, and identity discourse among individuals who are likely to be low-income and who have eaten at least once at CTEC.

Two additional elements of artificiality prevailed in our study. Taking a survey is an “abnormal” situation that often elicits views that are necessarily more deterministic and possibly more ephemeral, given the nature of surveys, than the more nuanced attitudes and beliefs, both conscious and subconscious, that guide respondents’ day-to-day discourse and ongoing behavior. Additionally, the civic action opportunity we offered CTEC guests required little risk or cost; guests’ responses to this opportunity may not have been representative of their willingness to act civically in more typical higher-risk, higher-cost situations.

Application

We believe the research reported here, although preliminary and restricted to a specific community context, nonetheless offers several possibilities for application in efforts to understand and address the problem of democratic quiescence among stigmatized individuals. Methodologically, our preliminary effort suggests that our mix of surveys and participant-observation, combined with a concurrent, observable opportunity to take civic action, may elucidate patterns in attitudes that can then be associated with civic quiescence and/or civic activity (Cresswell, 2003). Further work with these methods among more stable populations where random sampling techniques can be used can further explore the promise of these methods.

The willingness of some low-income individuals to participate in civic action, including the 66% of CTEC survey takers who signed petitions and/or wrote letters, may also have applicability for organizers in community settings. Our data strongly suggest that although behavior among individuals who belong to stigmatized groups (such as low-income individuals) can vary widely, organizers should expect to see a proportion of such individuals expressing political ideologies contradictory to their own best interests and should also anticipate resistance to participation among stigmatized individuals.

The high rate of civic participation we observed among guests at these two mealtimes suggests that quiescence may be reduced by removing practical barriers to civic participation, such as inconvenience, cost, and time (Levine, 2015). Perhaps just as importantly, CTEC guest remarks during these mealtimes supported the possibility that feelings of solidarity and the witnessing of civic activity by other guests played a role in the decisions of some CTEC guests to participate (Cerulo,

1997; Cohen, 1985; Gaventa, 1980, 2006b; Munger, 1992). The behavior of the CTEC guests we observed in this study suggests that community leadership must seek to understand the “invisible” dimensions of power that dampen citizens’ sense of their capacity to act. By placing opportunities for civic engagement into a community setting peopled largely by stigmatized individuals, we provided a living demonstration of stigmatized people taking civic action. While additional research is required to determine the exact nature of affiliative relationships that might be associated with enhanced willingness to engage in civic activity, our work nonetheless offers hope that finding ways to create demonstrable solidarity among the stigmatized can spark more widespread civic activity among them.

Conclusion

In sum, our ethnographic, survey, and civic-action data suggest a complex picture of civic agency among CTEC guests, with multiple factors playing into any given individual’s decision to take or not take civic action. Encouragingly, the findings presented here indicated that many CTEC guests were willing to take action toward advancing their own self-interests when given the chance, even in the face of pervasive societal and internal stigmatization. When offered a real opportunity to take part in civic action on an issue of immediate and significant concern to them, the majority of the individuals we surveyed did act. Furthermore, low-income guests whose responses to the survey indicated at least an ephemeral belief in “structuralist” explanations for poverty were significantly more likely to act than those who attributed poverty to individualistic causes. Though our study’s methodological limitations make the results ungeneralizable, our data support Gaventa’s ideas about the action-suppressing force of ideological colonization by dominant narratives. That said, exactly what forces sculpted any individual guest’s perceptions of the poor, as well as their susceptibility to self-stigmatization and civic quiescence, remain unknown. Therefore, more research in this area is needed.

Finally, it must be noted that although our study captured clear evidence (not reliant on self-reports) of a willingness to act civically among some low- income individuals, it had nothing to say about the civic efficacy of such individuals. Gaventa and Barrett (2010), Hillmer (2010), and Fung (2004) have all questioned whether active citizen participation necessarily leads to more just outcomes. Shortly after we completed data collection, and despite the letters and petitions we sent on behalf of the low-income individuals protesting the SNAP budget cuts, Congress cut benefits to SNAP by $8.5 billion over the next 10 years. Our study hints at some barriers to civic activity community organizers must address to combat quiescence, but clearly attention also needs to be paid to the conditions that enable grassroots civic activity to produce effective outcomes.

References

Atherton, C. R., Gemmel, R. J., Haagenstad, S., Holt, D. J., Jensen, L. A., Ohara, D. F., & Rehner, T. A. (1993). Measuring attitudes toward poverty: A new scale. Social Work Research and Abstracts, 29(4), 28-30.

Barrientos, A., & Neff, D. (2011). Attitudes to poverty in the ‘global village’. Social Indicators Research, 100(1), 101-114.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed- effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1-48. doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Bennett, E. A., Cordner, A., Klein, P. T., Savell, S., & Baiocchi, G. (2013). Disavowing politics: Civic engagement in an era of political skepticism. American Journal of Sociology, 119(2), 518-548.

Boydell, K. M., Goering, P., Morrel-Bellai, T. L. (2000). Narratives of identity: Re-presentation of self in people who are homeless. Qualitative Health Research, 10(1), 26-38.

Bullock, H. E. (1999). Attributions for poverty: A comparison of middle-class and welfare recipient attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(10), 2059-2082.

Cerulo, K .A. (1997). Identity construction: New issues, new directions. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 385-409.

Cozzarelli, C., Wilkinson, A. V., & Tagler, M. J. (2001). Attitudes toward the poor and attributions for poverty. Journal of Social Issues, 57(2), 207-227.

Cresswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dorey, P. (2010). A poverty of imagination: Blaming the poor for inequality. Political Quarterly, 81(3), 333-343.

Fung, A. (2004). Empowered participation: Reinventing urban democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gaventa, J. (1980). Power and powerlessness: Quiescence and rebellion in an Appalachian valley. Urbana, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gaventa, J. (2006a). Finding the space for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin, 37(6), 23-33.

Gaventa, J. (2006b). Assessing the social justice outcomes of participatory local governance. Unpublished report for the Local Governance Learning Group, Ford Foundation.

Gaventa, J. (2009). States, societies, and sociologists: Democratizing knowledge from above and below. Rural Sociology, 74(1), 30-36

Gaventa, J., Barrett, G. (2010). So what difference does it make? Mapping the outcomes of citizen engagement. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 347. University of Sussex.

Groskind, F. (1991). Public reactions to poor families: Characteristics that influence attitudes toward assistance. Social Work, 36(5), 446-453.

Handler, J. F., & Hollingsworth, E. J. (1969). Stigma, privacy, and other attitudes of welfare recipients. Stanford Law Review, 22(1), 1-19.

Hilmer, J. D. (2010). The state of participatory democratic theory. New Political Science, 32(1), 43-63.

Horan, P. M., & Austin, P. L. (1974). Social bases of welfare stigma. Social Problems, 21(5), 648-657.

Landis, J., & Koch, G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159-174.

Levine, A. S. (2015). American insecurity: Why our economic fears lead to political inaction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lott, B. (2002). Cognitive and behavioral distancing from the poor. American Psychologist, 57(2), 100-110.

Lukes, S. (1974) Power: A radical view. London: Macmillan. (Reprinted 2004, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Montgomery, C. (1994) Swimming upstream: The strengths of women who survive homelessness. Advances in Nursing Science, 16(3), 34-45.

Mosse, D. (2007). Power and the durability of poverty: A critical exploration of the links between culture, marginality and chronic poverty. CPRC Working Paper, 107, 1-157.

Mosse, D. (2010). A relational approach to durable poverty, inequality and power. Journal of Development Studies, 46, 1156-1178.

Munger, F. (2002). Identity as a weapon in the moral politics of work and poverty. In F. Munger (Ed.), Laboring below the line (pp. 1-25). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Reich, R. (2014, January 25). Why there’s no outcry. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-reich/why-theres-no- outcry_b_4666330.html

Rosenstone, S. (1982). Economic adversity and voter turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 26(1), 25-46.

Reutter, L. I., Stewart, M. J., Veenstra, G., Love, R., Raphael, D., & Makwarimba, E. (2009). “Who do they think we are, anyway?”: Perceptions of and responses to poverty stigma. Qualitative Health Research, 19(3), 297-311.

Snow, D. A., & Anderson, L. (1987). Identity work among the homeless: The verbal construction and avowal of personal identities. American Journal of Sociology, 92(6), 1336-1371.

Taylor, M., Howard, J., & Lever, J. (2010). Citizen participation and civic activism in comparative perspective. Journal of Civil Society, 6(2),145-164.

Williamson, J. B. (1974). Beliefs about the motivation of the poor and attitudes toward poverty policy. Social Problems, 21(5), 634-648.

Yadama, G. N., & Menon, N. (2003). Fostering social development through civic and political engagement: How confidence in institutions and agency matter. Social Development Issues, 25(1/2), 162-174.

Appendix A

Demographic Data from Community Table of Eau Claire, Final Quarter of 2013

Measure Percentage

Married (male) 5.0%

Widowed (male) 0.8% Divorced (male) 30.0% Separated (male) 6.7% Never married (male) 57.5% Housing unit occupied without payment of rent 8.3% Homeless 35.8% Rooming/board house 1.7% Transient hotel/motel 5.0% Housing unit rented for cash 25.0%

Mobile home/trailer 0.8%

Housing unit—owned or being bought by household member 4.2%

Paying to stay with friends or family 16.7%

Walk or bike to CTEC 50%

Drive car to get to CTEC 34.2%

Ride the bus to get to CTEC 18.3%

Carpool to get to CTEC 10%

Percent of CTEC guests earning less than $15,000 annually 94%

Percent of CTEC guests earning less than $5000 annually 56%

Appendix B

Survey Instrument Administered at Two Mealtimes at the Community Table of Eau Claire

1. Food Share makes people lazy

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

2. Food Share recipients should be able to spend their money as they choose

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

3. An able-bodied person using Food Share is ripping off the system

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

4. Society has a responsibility to help poor people

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

5. People on Food Share should be made to work for their benefits

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

6. Out-of-work people ought to have to take the first job that is offered

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

7. The government spends too much money on poverty programs

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

8. Poor people generally use Food Share wisely

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

9. Poor people have a different set of values than do middle-income people

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

10. The vast majority of people collecting Food Share benefits have which of the following attributes? Please circle all that express your opinion.

abuse alcohol/drugs, hardworking, family oriented, lazy, violent, physically ill, responsible, promiscuous, unlucky, stupid, capable, depressed, intelligent, healthy

11. Most poor people in this country have a chance of escaping from poverty

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

12. Why, in your opinion, are there people in this country who live in need? Here are two opinions: Which comes closest to your view?

- They live in need because of laziness and lack of willpower

- They live in need because society treats them unfairly

13. Generally speaking, we are spending too little money on Federal SNAP (Food Share) programs in this country

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

14. People are often ashamed of being on Food Share

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

15. Too many people on Food Share spend their money on drinking and drugs

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

16. Many women getting Food Share are having illegitimate babies to increase the money they get

Strongly Agree | Agree | No Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree

17. When was the last time you voted in a state or federal public election? Check all that apply.

- 2012 U.S. Presidential/Congressional election

- 2012 Wisconsin Recall election

- 2010 Wisconsin Governor/Congressional election

- 2008 U.S. Presidential/Congressional election

- 2006 Wisconsin Governor/Congressional election

- I have never voted

- prefer not to answer

If your answer to the above question was “I have never voted,” could you please explain why? Select all that apply.

- Lack of transportation

- Not registered to vote

- My vote doesn’t count

- Voting is time-consuming

- Voting issues don’t affect me

- I don’t agree with any of the candidates

- I am not concerned with voting issues

- Other:

SELF-STIGMATIZING BELIEFS SUPPRESS

Author Biographies

Ruth J. Cronje, PhD, is a Professor in the Rhetorics of Science, Technology and Culture program in the University of Wisconsin—Eau Claire’s Department of English. In addition to teaching courses in the rhetoric of science and medicine, she has taught courses in health justice and civic agency for the University Honors Program. In her role as Honors Faculty Fellow at the University of Wisconsin—Eau Claire, she has worked to form partnerships between the University and agencies in the Eau Claire area to address public problems.

Gregory T. Nelson graduated from the University of Wisconsin- Eau Claire with a BS in Environmental Public Health. While at UWEC he became interested in understanding the environmental determinants of public health including particulate pollution, sustainability issues, societal values, and politics. He has since gone on to pursuit a graduate degree in Botany at the University of Otago.

Kali J. Boldt is a MD-MPH dual degree student at the University of Wisconsin – School of Medicine and Public Health and recent Honors graduate from the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with a Bachelor of Science degree. In addition to studying, she has participated in research focusing on civic agency, health justice, and the social determinants of health related to critical literacy and health outcomes.

Laurelyn Sandkamp is a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. Student-faculty research at UWEC was a key foundational experience that prepared her for her public sector career. In her current role as an analyst for the City of Minneapolis, Laurelyn continues to apply her research and analytical skills and her commitment to public service.