By Petra Doan & Angela Lieber | The authors teach at a public university in the southeastern United States and, between them, have taught for more than 30 years in the social sciences and social work. They each identify as openly LGBTQ and have worked to incorporate their identities into their teaching about queer cultural competence. In this article, they reflect on their respective experiences and share key insights, including the need to create open and affirming classrooms, the importance of opening spaces for discussions with students about naming and pronouns, and the usefulness of course-specific LGBTQ materials in reinforcing the understanding that queer identity often intersects with racial and class positions to exacerbate a wide variety of planning and public policy issues.

Author Note

Petra Doan, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Florida State University; Angela Lieber, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Florida State University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Petra Doan, Professor, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Florida State University, 330 Bellamy Building, 113 Collegiate Loop, Tallahassee, FL 32306. Phone: (850) 644-8521. E-mail: pdoan@fsu.edu\

As two queer-identified instructors in a college of social sciences and public policy, we have experienced a variety of struggles and successes in creating an awareness of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) issues and how they relate to planning and public policy. Our experiences in this area span a wide range, providing useful insights for both established faculty and more recent higher education instructors. As a professor beginning her 29th year of teaching (the last 18 of which have been as an “out” transgender woman) and as a doctoral student and undergraduate instructor with four years of teaching experience, we utilize different teaching strategies that reflect our own subject positions and illustrate a diversity of practices for addressing queer cultural competence.

As two queer-identified instructors in a college of social sciences and public policy, we have experienced a variety of struggles and successes in creating an awareness of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) issues and how they relate to planning and public policy. Our experiences in this area span a wide range, providing useful insights for both established faculty and more recent higher education instructors. As a professor beginning her 29th year of teaching (the last 18 of which have been as an “out” transgender woman) and as a doctoral student and undergraduate instructor with four years of teaching experience, we utilize different teaching strategies that reflect our own subject positions and illustrate a diversity of practices for addressing queer cultural competence.

In the 1930s, the medical field highlighted the need to eliminate prejudice and embrace cultural differences that might constrain doctors’ ability to provide quality care to people of color (“Present Status,” 1935). During the 1970s, the broader field of public health, including doctors, nurses, and other public health providers, identified environmental factors and differential cultural practices as important influences on health outcomes (Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good, 1978). The idea of cultural competence emerged subsequently within the health professions to ensure that patients of color and persons from diverse cultural/religious traditions were provided the best possible care. One strategy for fostering cultural competence involved changing the content of training programs in medical and nursing schools, combined with recruiting a more diverse group of students. Other related fields focusing on counseling and social service provision, such as psychology (Sue, 1998) and social work (Ewalt, Freeman, Kirk, & Poole, 1996; Weaver, 1999), followed suit.

More recently, in medicine, social work, counseling, and clinical psychology, there has been a push to expand cultural competence pedagogies to more explicitly include LGBTQ perspectives (Baker & Beagan, 2015; Van den Bergh & Crisp, 2004; Wilkerson, Rybicki, Barber, & Smolenski, 2011). In social work, recent debate has centered on whether the desired affective, interpersonal, and knowledge outcomes that constitute “cultural competence” can be operationalized and taught (Jani, Osteen, & Shipe, 2016). The Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) set by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE)—the accrediting organization for bachelor’s- and master’s-level social work educational programs in the United States—do not address cultural competence as a discrete pedagogical objective but do include benchmarks for desired student outcomes around competencies related to engagement with diversity and issues of human rights, including engaging appropriately with sexual and gender diversity (see, e.g., CSWE, 2008, 2015). While the need for curricular content that will produce professionals who are capable of engaging respectfully and appropriately with queerness is explicit in social work pedagogy due to accreditation standards, Jani et al. (2016) pointed out that cultural competence is not perceived by social work educators and students as the most effective way to create competent practitioners. They argued, in part, that cultural competence lacks potency and utility as a pedagogical concept and that other factors might be more relevant to producing “competent” professionals, such as instructor self-awareness, content related to issues of power and oppression rather than contrived cultural groups, and maintaining classroom environments that support dialogue around structural issues of inequality (Jani et al., 2016).

Notwithstanding current debates regarding how to best transmit this desired yet elusive quality, the fields of planning and public policy have been slower to institutionalize pedagogical standards of cultural competence than medicine and social work and to address LGBTQ issues (Doan, 2015). This article explores our experiences as out queer women teaching and creating lesson plans to develop the next generation of planners and public policy analysts. In our approaches to “queering” cultural competence, we advocate for the integration of feminist, queer, and post-colonial frameworks that examine places, identities, and institutions as historical, relational, and socially constructed sites. Throughout our reflections, we weave explications of how we have used these theoretical frameworks and why we believe they are valuable analogs to cultural competence. Furthermore, we recognize that the inclusion of trans and gender non-conforming perspectives in planning and public policy education lags behind the inclusion of LGBTQ perspectives (Doan, 2011, 2015; Markman, 2011).

First Author’s Teaching Experience

My teaching experience over the past 20 years has been shaped profoundly by my own journey and struggle to come to terms with my transgender identity. In the mid-1990s, there was almost no discussion of lesbian or gay issues within the planning field. Rankin noted in 2003 that the climate on most campuses at that time was still inhospitable for such dialogue:

The literature from the past two decades reveals that the campus community has not been an empowering place for GLBT people and that anti-GLBT intolerance and harassment has been prevalent. A heterosexist climate has not only inhibited the acknowledgment and expression of GLBT perspectives. It has also limited curricular initiatives and research efforts, as seen in the lack of GLBT content in university course offerings. (p. 3)

While most of my departmental colleagues had heard something about this narrow identity called “transgender,” they had no direct personal experience with anyone claiming the complexity of such a fluidly embodied subjectivity. Most of the students were also in the same boat. Cultural competence around queer issues was nearly nonexistent.

In early 1998, when I informed my then department chair of my plans to transition in January 1999, there were no policies or procedures related to sexual orientation and gender identity in place at the college or university level.[1] Accordingly, I had to break new ground and “invent” a process for managing my coming out and building an awareness of trans issues, a kind of prototype for what today would be called queer cultural competence. The first step was to inform the graduate students in the department of the changes that were about to occur. In fall 1998, I asked the department chair to organize an information session with our graduate students to bring them up to speed on the upcoming changes as well as to provide opportunities for them to ask questions. Most of the students were somewhat stunned but also intensely curious. In my introductory remarks, I provided some basic information about sexual orientation and gender identity. I then used a bit of humor to suggest that while I was indeed a transsexual and taking female hormones (estrogen and progesterone), female hormones do not make people less intelligent and have no effect on one’s ability to understand complex planning issues. I did concede that there were “some physical changes to my body that are becoming more visible and that I might be a touch more emotional, but in our predominantly male department that might be a very good thing.” My sharing about deeply personal subjects clearly touched the students, empowering them to ask many questions about transgender issues and my experience of this particular gender identity. Generally, this strategy seems to have opened many people’s awareness about gender identity and sexual orientation, and a number of students approached me over the next few days after the information session and expressed their appreciation for my honesty and integrity, as well as their admiration for my undertaking such a difficult journey. Once more, I explained that “I do not feel like I have a choice; I am simply trying to survive.”

In spite of this preparation, when I began teaching in January 1999, I felt like I had arrived on campus in the middle of a tropical storm:

As I entered the building I felt I was entering the eye of a hurricane, at the calm center of a turbulent storm of gendered expectations. As I walked down the hall I could hear conversation in front of me suddenly stop as all eyes turned to look at the latest “freak show.” As I passed each office there was a moment of eerie quiet, followed by an uproar as the occupants began commenting on my appearance. (Doan, 2010, p. 642)

Fortunately, the intensity of the first few weeks of the semester passed quickly, and I assumed that the turmoil would quickly settle down. Because there was very little university support for gender and sexuality differences, I decided to focus on standard course content in my classes rather than shift the focus of the class to my own issues. In hindsight, this was not a good idea.

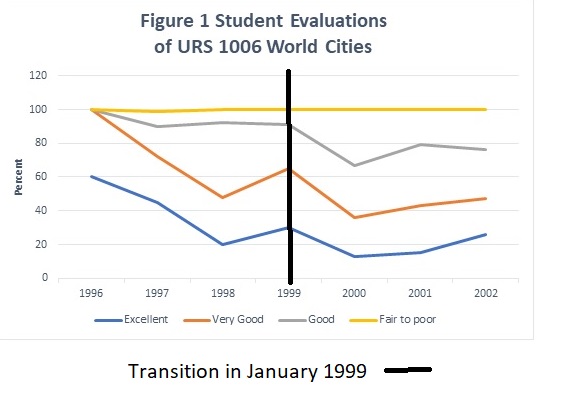

Teaching World Cities for Undergraduates

I was not able to host an information session for the students in my undergraduate World Cities class, since this was a very large liberal studies course. However, I realized after the semester that this was a serious error because the course evaluations showed how much I had upset some students who had had little exposure to LGBTQ issues. After transition, my teaching scores in that class dropped precipitously (see Figure 1). In prior years, my teaching scores—on an instructor rating scale of “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” and “fair to poor”—had been quite strong (45% “excellent,” 28% “very good”) and very few “fair to poor” ratings (9%). Yet, after my transition, the “excellent” and “very good” scores dropped to less than 10% each, the “fair to poor” ratings approached 40%, and the “good” ratings neared 50% in 1999. The following year, the increases in the “fair to poor” rating continued.

Figure 1. Student evaluations of URS 1006 World Cities.

These ratings can be explained in part by the open-ended questions that elicited comments suggesting that some students were outraged at having an openly transgendered faculty member. Their responses had little to do with teaching and nearly everything to do with sociocultural resistance to a gender identity that students simply could not comprehend. Many of the undergraduate students’ responses to several of the open-ended questions confirmed Boring’s (2017) findings regarding the inherent biases in student evaluations against women and, in this case, revealed a further bias against those who are non-normatively gendered:

-

- “Input a new teacher. S/he’s a man dressed like a female! It’s gross!”

- “How could a university hire a person who pretends to be female? It’s horrible! I recently explained to my parents that one of my professors is a man that had a sex change and she about lost it.”

- “Nice dresses.”

- “His [sic] gender confusion was very distracting.”

Clearly, many of these negative evaluations grew out of an inability or unwillingness of some students to understand LGBTQ difference, and certainly this adds to the increasing evidence that student evaluation scores are highly biased (Mitchell & Martin, 2018). However, at that time (i.e., in 1999), there was very little preparation available to the students that would have enabled them to situate my transition within the framework of cultural competence.

Teaching Urban Theory for Graduates

Over time, I have realized that I must incorporate my full awareness of gender issues into my teaching. I recognize that my identity is contingent and dependent on both social and cultural constructions of gender and space, which sometimes are at odds with the non-dichotomous nature of my gender. I am aware that expressing this non-normative gender may come at significant social costs, namely the “trade-offs in terms of such things as social power, social approval and material benefits” (Mehta & Bondi, 1999, p. 70). Unfortunately, gendered bodies are always observed and disciplined by a variety of social institutions, including the workplace, schools, families, prisons, and the military (Foucault, 1977). This regulatory regime creates and transmits power through repeated discourse intended to control sexuality by labeling homosexuality the “great sin against nature,” effectively othering that identity and any behaviors associated with it (Foucault, 1978). Jagose (1996) termed this othered identity queer, suggesting that it “describes those gestures or analytical models which dramatize incoherencies in the allegedly stable relations between chromosomal sex, gender, and sexual desire…. Queer focuses on mismatches between sex, gender, and desire” (p. 3). I call those who inflict this discursive power on my queerly gendered body the “gender police.”

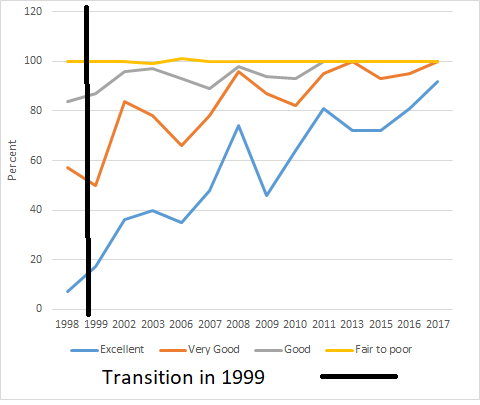

My persistence in presenting to my classes my full and authentic self—with my large body size (6’2”) and very deep voice—often triggers a useful kind of gendered cognitive dissonance for students. At the same time, my openness about difference helps to create a more inclusive learning environment where students are empowered to embrace differences and encouraged to share more openly about a variety of issues. In addition, I began adding explicit readings that highlight the ways in which LGBTQ concerns are indeed linked to planning issues (Dubrow, 1998; Forsyth, 2001; Frisch, 2002). As a result, my teaching scores began to rebound, and once again I was one of the more highly regarded instructors in the department. As Figure 2 shows, in fall 1998, when students first learned of my upcoming gender transition, my student evaluation scores in a required graduate class were similarly low, with very few ratings in the “excellent” and “very good” categories, and nearly 40% indicating “fair to poor” instruction. However, within 10 years, these ratings reversed completely, and by 2017, 92% rated my instruction as “excellent.”

Figure 2. Student evaluations of URP 5847 Growth of Cities.

Change is clearly possible and, in my case, was likely linked to the level of cultural competence I provided the students around LGBTQ issues. The strategies I used in this large core graduate class included a series of steps designed to create an inclusive classroom. Generally, this class often consists of more than 25 and sometimes as many as 50 students, making it challenging to hold discussions. However, I stress to students from day one that the intent of the class is to provide them with a “mixed bag” of theoretical and practical tools with which to understand the ways cities grow and change over time and the diversity of people who live in them. By sharing a little about my own journey toward a more activist role (Doan, 2017), I lay the groundwork for students to consider the roots of their desire to enter the field of planning and to discover their own sources of activism.

I have developed units in this urban theory class that explicitly consider the ways that race and gender have influenced city planning. I discuss, for instance, June Manning Thomas’ (1998) powerful insight that “city improvement efforts in the context of racial oppression, can be racially oppressive” (p. 201) and then suggest that in similar fashion urban planning in the face of heterosexist and transphobic oppression is likely to result in policies and plans that are heterosexist and transphobic. In addition, I incorporate a unit on understanding ethnic enclaves and draw a parallel with the evolution of LGBTQ neighborhoods (Abramson, 1996; Dubrow, 1998; Rojas, 2010; Thomas & Darnton, 2006). When the class examines the influence of gender on perceptions of safety, I suggest that a fuller understanding of intersectional identities (see, e.g., Brown, 2014; Crenshaw, 1991; Johnston, 2018; Valentine, 2007) adds useful insights about the ways that men and women perceive spaces differently but, even more importantly, also influences the ways that people of color, those who identify as LGBTQ, and people who identify as some combination of both might perceive urban spaces. Several comments from the open-ended section of the student evaluations provide corroborating evidence about the effectiveness of this approach:

- “I loved the way [Dr. Doan] taught this course. She opened up my mind to new theories and principles which never crossed my mind. She created a very safe, warm and comfortable atmosphere in the classroom which encouraged student participation and created a safe place for everyone to be themselves.”

- “I am able to look at cities, spaces, and even human interaction in a different light; and I appreciate the safe spaces that you create within your classroom.”

- “[Dr. Doan] provides an inclusive learning experience while continuously pushing the boundaries of comfort to widen the perspectives of her students.”

In my other graduate courses, I also integrate a unit on how LGBTQ identity links to issues related to planning and global development. I suppose I am consciously “mainstreaming” LGBTQ issues into these classes to create space for students to think more broadly about the ways that difference might influence issues like land tenure, housing in so-called “squatter settlements,” and even in the construction of planning and project proposal documents. I emphasize that I am not “exporting” my identity anywhere but am simply recognizing that on a global scale there are so many diverse subject positions that students must be careful about making assumptions.

As made clear by my evaluation ratings, teaching after a gender transition at a large public university can be quite challenging. However, a more indicative measure of the way that I have been queering the cultural competence of the department is the fact that, since my transition, I have several times been nominated for university teaching awards and on one occasion received a graduate advising nomination. In fall 2012, I received a Transformation through Teaching Award based on a student nomination that described the way my teaching had been transformational for that student. As the only visibly out faculty member in the department and one of the most visible in my college, I am often sought out by students needing to talk about issues related to their sexual or gender identity, or to find a supportive place to explore their place in the planning profession.

Second Author’s Teaching Experience

As a queer person with a background in LGBTQ advocacy and research, my assumption starting out in undergraduate social work instruction was that I should focus less on the foundational vocabularies of sexual and gender diversity (e.g., making sure social work students knew relevant concepts/terminology and prevalent social, health, and behavioral health risks in working with LGBTQ populations) and more on the nuances of gender and sexuality as they overlapped with other forms of structural oppression and with other sociocultural categories. My experiences in trying to cultivate queer cultural competence among students have both challenged and supported this initial approach. My personal intuition around thinking about queerness and/or gender diversity has been that “operationalizing” sexual and gender phenomena into discrete teachable categories and definitions tends to steer learners into the related pitfalls of essentialization and fetishization, and I think my desire to avoid this is what framed my earliest attempts to instill competence around LGBTQ people and ideas. There are many ways to be queer, many ways to embody and enact sexuality and gender, many ways sexuality and gender have been and are mobilized and implicated within other projects of empowering or restricting people’s and community’s agency and realities. These ways of promoting or containing gender and sexuality—even modern and so-called progressive LGBTQ identity building in the neoliberal state—can simultaneously liberate and suppress coevals, as Sara Ahmed (2005) astutely observed about socio-politically privileged notions of the truly liberated queer as necessarily individualistic and transgressive of both norms and space: “The idealization of movement, or transformation of movement into a fetish, depends on the exclusion of others who are already positioned as not free in the same way” (as cited in Puar, 2007, p. 22). I discuss this here in relation to my attempts to facilitate queer and gender-inclusive competence at its intersections with race, space, class, and political citizenship. In my feedback from both students and observing faculty, one of the most common criticisms is, “Needs to provide more concrete definitions.” Thus, first, what follows are some key takeaways from where I was wrong in wanting to overlook basic queer and gender-inclusive vocabularies and issues.

Lectures on Gender with Social Work Students

In fall 2016, I developed a lecture on gender to deliver to two different undergraduate sections of a social work course titled Social Justice and Diversity. The curriculum for the course includes competencies that respond to the EPAS set by the CSWE. As mentioned previously, the EPAS do not include an explicit standard for cultural competence. However, expanding students’ cultural competence is one of the primary objectives for the Social Justice and Diversity course; this desired outcome corresponds in the course syllabus to EPAS Competence 2, “Engage Diversity and Difference in Practice,” mentioned earlier in this article (CSWE, 2015; the version referenced in the 2016 course syllabus is from the revised 2008 EPAS, which is Educational Policy 2.1.4 [CSWE, 2008]). The EPAS competence includes gender, gender identity and expression, sex, and sexual orientation in terms of engaging diversity. At the beginning of both sessions, I introduced myself and told students what gender pronouns I use; I provided students the materials to create name tents for their desks that also included their gender pronoun information. I assumed incorrectly that gender pronouns would be acknowledged cursorily by the students and that they would not become the focal point of any of the “meatier” conversations during the session. At the time, I had a partially shaved head, which in many social settings in the United States is interpreted as somewhat transgressive of acceptable hair standards for a white person who usually registers outwardly as a “woman.” I shared stories with the students about manipulating my presentation to be more “butch” or “femme,” cross-dressing publicly (which I also often do, including in how I present as an instructor), and how my relative androgyny versus ability to be more “easily” categorized on the gender binary seemed to affect the ways in which I was socially consumed in various spaces.

Students also shared examples of their own behaviors and presentations of self (whether consciously queer or gender-transgressive or not) and how they perceived their examples to be read as queer/not queer by other people. One student used an example of kissing on the cheek between friends and family, including those who are registered by others as belonging to the same gender, as a cultural custom that is perceived as homosexual behavior within many social settings in the United States. In both sessions, we complemented discussion of pronouns and gendered/sexualized social interpretations of behaviors with a viewing of an episode of the docu-series This is Me (Ernst & Aranda, 2015), which explores the importance of being cognizant of people’s names and pronouns, as well as some experiences of being publicly misgendered from the perspective of two genderqueer/queer artist-advocates affiliated with the popular television series Transparent.

Finally, I provided students with Gender/Sexual Orientation 101 and Crash Course on Non-Binary Identities (available from tiny.cc/VernHarner), resources developed by Vern Harner, social work doctoral student and trans advocate who develops educational materials and provides consultation for instructors from all disciplines wanting to cultivate affirming spaces. Many students, in feedback regarding their takeaways from the lectures, identified new concepts and terminology (e.g., use of gender-neutral pronouns) they had learned from these supplemental materials.

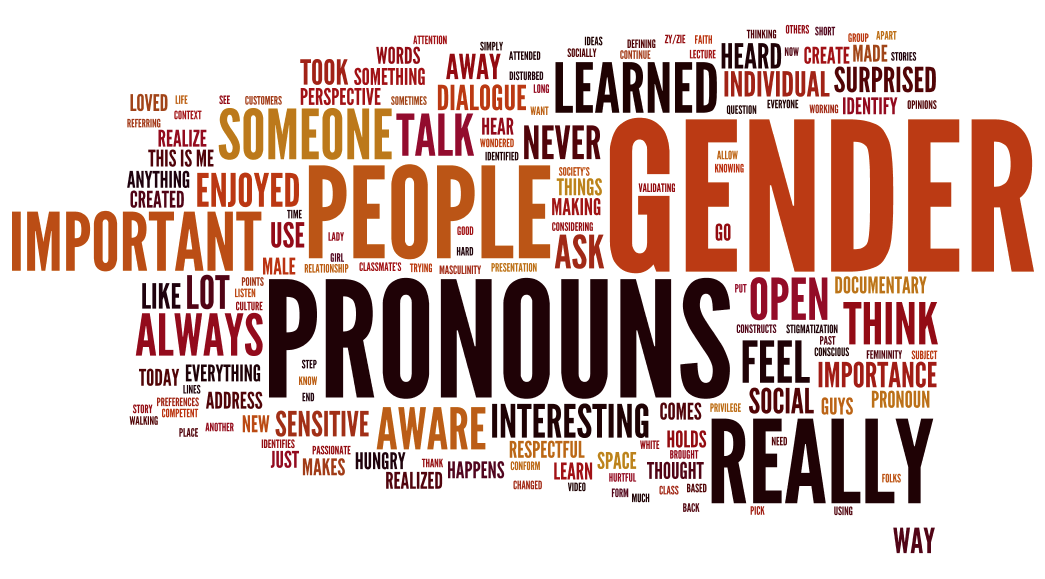

I believe the space created in these classrooms for respectful curiosity, baseline education about concepts such as gender pronouns, and open dialogue facilitated a helpful balance in the division of emotional labor involved in gaining cultural competence about queer and transgender or gender non-conforming topics. Students were encouraged to both listen to the ways in which queer and gender-diverse people experience violence resulting from binaried (and heterosexist) sociopolitical configurations and also to examine the ways their own experiences invest in/benefit from (or are limited by) such configurations. As a surprise to me, pronouns were among the most prevalent concepts students wrote about in their feedback (see Figure 3). Obviously, providing students with baseline knowledge surrounding queer and gender-transgressive identities is not the equivalent or endpoint of promoting cultural competence. However, given the short amount of time and space, I was impressed with the reflexivity with which these undergraduate students engaged in and seemed to desire concepts of queer and trans inclusivity when presented with the aforementioned materials and ideas. This reflexivity illustrates the importance of classroom environment and engaging dialogue in teaching about the multiplicities of culture and subjectivity. In addition to providing the baseline concepts and vocabulary for being able to talk about gender (mastery of any so-called culture is an essentializing fantasy), I suggest that it is crucial to create a space in which students are asked to reflect on and discuss the way gender as a constructed category affects and is affected by them. Contrary to the idea that gender and sexual diversity are located in an ideal body that represents such subjectivities as trans or genderqueer, which I identify as a fetishizing impulse, I have found it useful to engage gender and sexuality as “problems” for everyone. This requires content for teaching familiarity with basic concepts and relevant information, and also, importantly, an inclusive space as well as an impetus to reflect and engage in dialogue.

Figure 3. Word cloud generated from student feedback forms from two gender-diversity lectures given in fall 2016. A total of 34 feedback forms were collected for both classes. The relative sizes of the words in the clouds represent their frequencies in an analysis of the combined raw text derived from feedback forms from both lectures. Created on Wordle.net.

The following excerpts from students’ feedback illustrate the attentiveness and emotional/intellectual labor they invested in the lectures with regard to gender inclusivity:

- “[It] brought to my attention that it is good for your social constructs to be disturbed and to force you to think about respecting people’s pronouns…. I love your openness and willingness to share personal stories.”

- “I learned today that it is important to ask an individual for their pronouns and respect it because this will create a space for the individual which will create a strong and meaningful relationship.”

- “You put into words the kind of reflection that happens when someone asks for my pronouns, considering I’ve never not identified as a ‘woman’. I want to continue exploring the blurred lines between the way I ‘conform’ to the way I do womynhood [sic] and the ways I don’t.”

- “You really allowed for us to dig deep within ourselves and talk about things we may not have.… I didn’t realize how important pronouns were in the context of referring to people. I really didn’t know about cisgender and all of those pronouns. I feel like I am walking away more aware and hungry to learn more about gender! You made me hungry to learn more and be more aware because it is important!”

- “Discussing gender made me realize how important making opportunities for dialogue about it is. I realized I have another opportunity to do this during my culture presentation.”

Teaching Gender and Sexuality Competence in a Policy Course

In spring 2017, I taught Social Welfare Policies and Programs, a relatively generic course in terms of its adaptability to other undergraduate courses providing an overview of social/public policy and policy analysis, although it is distinctly orientated toward clinical work that is less applicable. In this section, I reflect briefly on my attempt to incorporate some of the practices/content outlined earlier in the context of a semester-long course as well as some additional ways I approached sexuality and gender at their intersections with other identity categories in deconstructing and analyzing various social policies. The major areas covered in this course included (in a U.S. context) the following: policy and politics of mental health; poverty and programs to assist the poor; policies and politics concerning civil rights, with focuses on race, women, LGBTQ communities, and sex workers; health care politics and policy; politics and policy of housing and homelessness; substance-use politics and policy; politics and policy of im/migration; and politics and policies concerning children and youth.

Like the first author, I consider the creation and maintenance of an affirming classroom environment—especially for trans or gender non-conforming and queer students—to be foundational to cultivating inclusivity and affirmation around sexuality and gender identity in students as future professionals in the fields of policy or public service. Practical steps I took in approaching this goal included reinstating the name tents I had used during the earlier guest lectures that included gender pronouns, as well as introducing my own pronouns beforehand and facilitating a conversation about this; indeed, it was also important that we used these name tents as reminders every class, not simply as a novelty for the first class. I also included my gender pronouns on the course syllabus and habituated my own use of gender-inclusive language inside and outside of the classroom (e.g., “they” for singular personal pronouns, especially of someone outside the classroom and/or a person who had never disclosed their pronouns to me personally, as well as inclusive plural/collective personal pronouns, such as “you all,” “everyone,” “comrades,” “y’all”)—a practice related to everyday classroom management and interaction that any faculty member wanting to cultivate cultural competence around queer and gender non-conforming/trans/non-binary identities can adopt.

In addition to including a course module more specific to policies and politics directly relevant to the well-being of transgender, gender non-conforming, and queer people, I encouraged students to engage in the admittedly difficult intellectual and emotional labor of approaching concepts related to gender and sexuality intersectionally as they analyzed and deconstructed all other policy areas. One example of this task was our course module on U.S. policy interventions related to providing assistance to the poor. In this unit, we analyzed the racism embedded in welfare policy (e.g., Piven, 2003), focusing on the policing of Black women’s sexuality and its relationship to the racialized sexual stereotypes employed to limit Black agency and dehumanize Black bodies during chattel slavery (see also Tinsley, 2008 regarding queerness and the Middle Passage). We also analyzed social class and the relationship between poverty and health, allowing students to make connections to racial as well as sexual and gender-based marginalization and the relationships between these identity markers and social goods, such as health insurance and paid time off/employment policies (Grant et al., 2010; Scott, 2005).

Teaching at interstices and overlapping areas of identity and policy has been helpful to me in avoiding fetishizing or essentializing particular identities or bodies as either desired objects or archetypal examples of sexual, gender, and other social phenomena associated with diversity. In examining different ways policy affects and is affected by relationships, the object of analysis becomes the relationship rather than a particular stereotype of identity or disadvantage. Using and expanding on another example from Social Welfare Policies and Programs, my students and I analyzed some of the politics and policies related to housing, including gentrification, U.S. zoning laws, and the commodification of housing. Using the case example of the Take Back the Land movement based in urban southern Florida (Rameau, 2008), students deconstructed the contexts of and relationships to power that lead land-grabbing/appropriation actions to be interpreted “favorably” in some scenarios and “unfavorably” in others, and why queer, trans, and communities of color have typically been portrayed negatively both in instances of dispossession and possession (e.g., as “squatters” in the instance of Take Back the Land).

Courses in policy related to urban and regional planning can introduce sexuality and gender competence by exploring settler colonialism in the United States and elsewhere, namely the relationships between aggressive dispossession, nation-building/the liberal state, racialization and sexualized/gender-based violence—processes that continue to disproportionately mark relationships and bodies that transgress norms dictated by prevailing sexual and gender economies for violence and dispossession (Morgensen, 2010; Rifkin, 2011; Wilm, 2017; for a good general definition of post-colonialism, see Ashcroft, Griffiths, & Tiffin, 1998). These relationships are embedded in current imaginaries of territory, land use, and possession more broadly, and understanding them in historical contexts allows students to examine sexuality and gender in terms of relationships, not merely categories. As another example, examining current politics and policies around gender-affirming bathrooms could (and I think should) open doors to discussing constructed dichotomies between public and private space, as well as the use of space to create scenes of division, segregation, and, more broadly, irreconcilable difference (Dear, 2013; Doan, 2010).

Lessons Learned

Our combined experiences suggest that a critical component of queering cultural competence involves creating and maintaining affirming and inclusive classrooms that encourage students to bring their full subjectivities to class. When instructors are open about difference, it helps students to explore and create spaces for a range of subject positions. Naming appropriate gender pronouns up front on the syllabus and using name and pronoun “tents” on student desks, for instance, can serve as effective mechanisms for opening rich discussion about gender and identity that will significantly enhance LGBTQ cultural competence, irrespective of the queer or non-queer subjectivity of the instructor. Additionally, conversations with students that elicit reflection and dialogue about different experiences with gender and sexuality norms—perhaps as a secondary benefit of facilitating inclusivity in the classroom—can open doors to theoretical content in non-threatening ways that resonate with quotidian experience. As in the earlier example, encouraging all students to reflect on how they “do,” or are perceived as doing, gender can allow for a dialogue surrounding gender performativity (Butler, 1990; West & Zimmerman, 1987); emerging conversations in queer theory regarding performativity and passing with relation to coloniality and racialization would also fit well into such conversations (e.g., Massad, 2002; Puar, 2007, 2017).

The second author has found feminist and Black feminist theory to be helpful in encouraging students to think about the ways that structural patriarchy and institutionalized forms of oppression—especially racism/racialization (including white feminism)—mark the bodies and lives of women and femme-identifying people of color. These conversations were instrumental, for example, in teaching about welfare policy, the policing of feminine sexuality and bodies (as well as the feminization of bodies), and the relationship of these to colonial interventions of dispossession and violence toward community (e.g., Chatterjee, 2012; Delphy, 2015; Piven, 2003; Rifkin, 2011).

Other strategies more closely linked to topical material include asking students to share with their classmates their motivations for studying urban planning and/or public policy. Furthermore, assigning readings with explicit LGBTQ perspectives on perceptions of urban spaces and differential needs for creating gathering spaces and forming neighborhood can reinforce the understanding that while the vast majority of individuals live in cities, they each experience them quite differently. In addition, course material can be diversified both temporally (e.g, informed by a deeper historical analysis) and topically to help students understand the ways that current paradigms of study and professional practice, including planning, social welfare policy, and public policy more broadly, intersect with race, class, and a range of intersectional identities, including LGBTQ status. The social work literature (Jani et al., 2015) highlights an ongoing debate regarding the relative benefits and disadvantages of “stand-alone” and “infusion” models, the former referring to courses that specifically cover issues of marginalization, power/oppression, or specific cultural or subcultural groups, and the latter referring to the inclusion of such material throughout the curriculum of courses not necessarily centered on topics related to cultural competence per se. Discussions in social work about these various approaches could inform the development of more intentional pedagogy for teaching queer competence in planning and other public policy-oriented fields.

Although there are differences in our respective approaches to establishing queer cultural competence, some of these differences can be explained by the very different social and cultural environments between the late 1990s and the present day. The first author’s experiences of overcoming outright hostility among her undergraduate students and grudging acceptance by colleagues and graduate students clearly shaped her approach to teaching about subjects that were rarely discussed in the field of planning. The second author faced an undergraduate classroom where students had had much greater exposure to a wide range of LGBTQ issues in the news and in their daily lives. A much higher percentage of the current generation of students are identifying as gender non-conforming or have friends, family members, or acquaintances who may be non-conforming. Even so, the results of the 2016 presidential election have raised some distressing questions about whether the acceptance of queer individuals and families (marriage equality and overall rising levels of LGBTQ social acceptance) may be reversed or is, at the very least, the subject of repeated social media attacks.

Queer cultural competence is critical in a field such as urban planning since many of our graduate students will either work directly for elected local officials or have their consulting reports evaluated and approved by such officials. If planners wish to create plans and policies that are truly inclusive of LGBTQ individuals and families, they need to understand at a deep level the issues and concerns that are faced by this community so that they can make convincing arguments in the face of local officials who may be skittish about taking on “politically charged” issues related to the LGBTQ community.

References

Abramson, M. (1996). Urban enclaves: Identity and place in America. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Ahmed, S. (2005). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., & Tiffin, H. (1998). Key concepts in post-colonial studies. New York: Routledge.

Baker, K., & Beagan, B. (2015). Making assumptions, making space: An anthropological critique of cultural competency and its relevance to queer patients. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 28(4), 578-598.

Boring, A. (2017). Gender biases in student evaluations of teaching. Journal of Public Economics, 145, 27-41.

Brown, M. (2014). Gender and sexuality II: There goes the gayborhood. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 457-465.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble. New York: Routledge.

Chatterjee, I. (2012). Feminism, the false consciousness of neoliberal capitalism? Informalization, fundamentalism, and women in an Indian city. Gender, Place, and Culture, 19(6), 790-809.

Council on Social Work Education (Ed.). (2008). Educational policy and accreditation standards (Rev. ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Council on Social Work Education (Ed.). (2015). Educational and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. doi:10.2307/1229039

Dear, M. (2013). Why walls won’t work: Repairing the U.S.-Mexico divide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Delphy, C. (2015). Separate and dominate: Feminism and racism after the war on terror (D. Broder, Trans.). Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Doan, P. L. (2010). The tyranny of gendered spaces: Living beyond the gender dichotomy. Gender, Place and Culture, 17, 635-654.

Doan, P. L. (2011). Queerying planning: Challenging heteronormative assumptions and reframing planning practice. Farnham: Ashgate.

Doan, P. L. (2015a). Planning and LGBTQ communities: The need for inclusive queer space. London: Routledge.

Doan, P. L. (2015b). The tyranny of gender and the importance of inclusive safe spaces in cities. Presentation delivered at TEDxFSU, Turnbull Center, Florida State University.

Doan, P. L. (2017). Coming out of darkness and into activism. Gender, Place, and Culture, 24(5), 741-746. doi:10.1080/0966369x.2017.13

Dubrow, G. (1998). Blazing trails with pink triangles and rainbow flags: New directions in the preservation and interpretation of gay and lesbian heritage. Historic Preservation Forum, 12(3), 31-44.

Ernst, R. (Director), & Aranda, X. (Producer). (2015). Episode 4: Right this way [Docu Series Episode]. In J. Soloway (Executive producer), This is me. Wifey TV. Retrieved from http://wifey.tv/video/this-is-me-right-this-way/

Ewalt, P., Freeman, E., Kirk, S., & Poole, D. (Eds.). (1996). Multicultural issues in social work. Washington, DC: NASW Press.

Forsyth, A. (2001). Sexuality and space: Nonconformist populations and planning practice. Journal of Planning Literature, 15, 339-358.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality, volume 1: An introduction. (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Random House.

Frisch, M. (2002). Planning as a heterosexist project. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 21(3), 254-266.

Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Herman, J. L., Harrison, J., & Keisling, M. (2010). National transgender discrimination survey report on health and health care. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Jagose, A. (1996) Queer theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Jani, J. S., Osteen, P., & Shipe, S. (2016). Cultural competence and social work education: Moving toward assessment of practice behaviors. Journal of Social Work Education, 52, 311-324.

Johnston, L. (2018). Intersectional feminist and queer geographies: A view from ddown-under.” Gender, Place, and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 25(4), 554-564.

Kleinman, A., Eisenberg, L., & Good, B. (1978). Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Annals of Internal Medicine, 88(2), 251-258.

Markman, E. (2011) Gender identity disorder, the gender binary, and transgender oppression: Implications for ethical social work. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 81(4), 314-327.

Massad, J. (2002). Re-orienting desire: The gay international and the Arab world. Public Culture, 14, 361-385.

Mehta, A., & Bondi, L. (1999). Embodied discourse: On gender and fear of violence. Gender, Place, and Culture, 16, 67–84.

Mitchell, K. M. W., & Martin, J. (2018). Gender bias in student evaluations. PS: Political Science and Politics, 51(3), 1-5. doi:10.1017/S104909651800001X

Morgensen, S. L. (2010). Settler homonationalism: Theorizing settler colonialism within queer modernities. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 16, 106-131.

Piven, F. F. (2003). Why welfare is racist. In S. Schram, J. Soss, & R. Fording (Eds.), Race and the politics of welfare reform (pp. 323-335). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Present status of the Negro physician and Negro patient. (1935). Journal of the National Medical Association, 27(2), 79-80.

Puar, J. K. (2007). Terrorist assemblages: Homonationalism in queer times. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Puar, J. K. (2017). The right to maim: Debility, capacity, disability. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rameau, M. (2008). Take back the land: Land, gentrification, and the Umoja Village shantytown. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Rankin, S. (2003). Campus climate for sexual minorities: A national perspective. New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute.

Rifkin, M. (2011). When did Indians become straight? Kinship, the history of sexuality, and native sovereignty. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rojas, J. (2010). Latino urbanism in Los Angeles: A model for urban improvisation and reinvention. In J. Hou (Ed.), Insurgent public space: Guerrilla urbanism and the remaking of contemporary cities (pp. 36-44). New York: Routledge.

Scott, J. (2005). Life at the top in America isn’t just better, it’s longer. In Correspondents of The New York Times (Eds.), Class matters (pp. 27-50). New York: Times Books.

Sue, S. (1998). In search of cultural competence in psychotherapy and counseling. American Psychologist, 53(4), 440-448.

Thomas, J. M. (1998). Racial inequality and empowerment. In L. Sandercock (Ed.), Making the invisible visible: A multicultural planning history (pp. 198-208). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Thomas, J. M., & Darnton, J. (2006). Social diversity and economic development in the metropolis. Journal of Planning Literature, 21(2), 153-168.

Tinsley, O. N. (2008). Black Atlantic, queer Atlantic: Queer imaginings of the Middle Passage. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 14(2-3), 191-215.

Van Den Bergh, N., & Crisp, C. (2004). Defining culturally competent practice with sexual minorities: Implications for social work education and practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 40(2), 221-238.

Valentine, G. (2007). Theorizing and researching intersectionality: A challenge for feminist geography. The Professional Geographer, 59(1), 10-21.

Weaver, H. (1999). Indigenous people and the social work profession: Defining culturally competent services. Social Work, 44, 217-225.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender and Society, 1, 125-151.

Wilkerson, J. M., Rybicki, S., Barber, C. A., & Smolenski, D. J. (2011). Creating a culturally competent clinical environment for LGBT patients, Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 23(3), 376-394.

Wilm, J. (2017). Poor, white, and useful: Settlers in their petitions to U.S. Congress, 1817-1841. Settler Colonial Studies, 7, 208-220.

Author Biographies

Petra Doan is Professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Florida State University. In addition to her research on planning in the developing world, she conducts research on planning issues and the LGBTQ community. She has edited two books: Queerying Planning: Challenging Heteronormative Assumptions and Reframing Planning Practice published in 2011 by Ashgate and Planning and LGBTQ Communities: the Need for Inclusive Queer Space published by Routledge in 2015. She also publishes in Gender, Place, and Culture, Women’s Studies Quarterly, Environment and Planning A, the International Review of Urban and Regional Research, the Journal of Planning Education and Research, and Progressive Planning.

Petra Doan is Professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Florida State University. In addition to her research on planning in the developing world, she conducts research on planning issues and the LGBTQ community. She has edited two books: Queerying Planning: Challenging Heteronormative Assumptions and Reframing Planning Practice published in 2011 by Ashgate and Planning and LGBTQ Communities: the Need for Inclusive Queer Space published by Routledge in 2015. She also publishes in Gender, Place, and Culture, Women’s Studies Quarterly, Environment and Planning A, the International Review of Urban and Regional Research, the Journal of Planning Education and Research, and Progressive Planning.

Angela Lieber is a first-year doctoral student in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Florida State University. Angela’s interests are queer/ed identities and bodies in time and space, especially in their historical and present uses (and abuses) as planes of constructing and registering difference. Angela hopes to produce work that contributes to safer and more affirming experiences of space and mobility for people who are queer.

Angela Lieber is a first-year doctoral student in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Florida State University. Angela’s interests are queer/ed identities and bodies in time and space, especially in their historical and present uses (and abuses) as planes of constructing and registering difference. Angela hopes to produce work that contributes to safer and more affirming experiences of space and mobility for people who are queer.