Author Note

James J. Krotz, Department of Animal Sciences, Purdue University; Lisa M. Rubin, Department of Special Education, Counseling, and Student Affairs, Kansas State University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to James J. Krotz, Senior Academic and Career Advisor, Department of Animal Sciences, Purdue University, CRTN 1058, West Lafayette, IN 47906. E-mail: jkrotz@purdue.edu

Abstract

College students have a legitimate interest in many policy issues that affect their campuses, but are they effective in lobbying their state representatives in support of their interests? In the study discussed in this article, the authors surveyed elected members of the Kansas state legislature to determine if student lobbyists were effective in influencing legislators’ decision making around matters of public higher education policy in Kansas. The researchers applied interest group theory to analyze legislator perceptions. The study findings indicated that 70% of legislator participants did not alter their perception of an issue after meeting with a college student lobbyist. In addition, the results showed that legislator responses aligned with partisan politics, with Democrats more likely to understand and empathize with the perspectives of college students than their Republican colleagues.

Public higher education interest groups in many states are operating under increasingly constrained budgets. Moreover, many higher education lobbying professionals must contend with negative views of their institutions and increased pressure from legislators to justify the funds they receive from public coffers. In light of such complications, higher education governmental relations professionals in the state of Kansas are seeking to harness the enthusiasm and passion of students to help achieve their lobbying objectives. The formation of new advocacy groups and activism campaigns, the organization of student visits to the capitol and legislator visits to campuses, and efforts to match legislators with student constituents demonstrate a readiness to embrace student involvement in state politics. However, the question remains: How do legislators actually perceive these new student advocates? The purpose of this study was to understand legislators’ perceptions of student lobbyists and to develop more effective strategies for students to influence public policy.

Theoretical Framework

Since this study drew heavily from the field of political science, it was only appropriate to use a theory from that field—interest group theory—as a framework. Interest group theory posits that individuals will coalesce around a shared cause with the goal of influencing legislators to enact their proposals (Cigler & Loomis, 2011). This is hardly a new concept. The first petitions seeking to influence legislation came from a variety of groups during the country’s founding, including merchants, shipbuilders, clerks, and veterans (Byrd, 2006; Swanstrom, 1988).

Higher education can legitimately be considered an interest group within state policymaking (Thomas & Hrebenar, 2004), and higher education institutions and the professional in-house and contract lobbyists they employ are manifestations of interest group theory. These professionals, usually lobbying on behalf of public institutions for more state funds, work strategically in the institution’s interest as well as the students’. The presence of professional higher education lobbyists has been shown to impact public policy (Tandberg, 2010). Tandberg (2010) also outlined that the increasing number of interest groups in political systems often lead to natural alliances and greater impact. Public universities are natural allies in their competition with other sectors for more public funding, especially when they share a governing structure, as is the case in Kansas and many other states with a central Board of Regents (Tandberg, 2010). Clearly, professional higher education lobbyists have the potential to play a significant role in shaping policy.

College students also have a long history of influencing public policy, although their methods have differed markedly from those of professional lobbyists. The civil unrest and protests on college campuses in the 1960s played a considerable role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act (Blumberg, 1991; Flacks, 1967). Today, in the vast, ever-changing world of professional politics, college students continue to drive change through organizing, while universities, corporations, nonprofit entities, and foreign interests influence public policymaking in unprecedented ways (Loomis & Cigler, 2011). Interest group theory contends that if college students want to have the same kind of outsize influence as the institutions they attend, they must find ways to gain legitimacy in the eyes of their conservative state legislators.

Review of Literature

The existing literature on public interest groups and their effectiveness in influencing public policy is extensive (Potter, 2003). However, the body of literature on lobbying in higher education is less well developed, and more limited still is the literature on student lobbyists in state legislatures (Benveniste, 1985; Burgess & Miller, 2009; Longo, 2004). As Cook and McLendon (1998) noted, the literature around the politics of higher education has suffered from “benign neglect” (p. 186).

Despite the relatively narrow body of literature on higher education lobbying, the scholarship on interest groups has overwhelmingly shown that state-level interest group activity impacts public policy in a variety of ways within a state (Tandberg, 2010). Additionally, although there is considerable debate about whether interest groups—and the outside or “dark” money some of them possess in abundance—help or hinder democracy, they are a natural occurrence when like-minded individuals or economic sectors share a common goal (Lowery, 2007). Higher education institutions are no exception. In-house lobbyists constantly initiate, cultivate, maintain, and monitor relationships in the interests of their institutions (Ferrin, 2005). Indeed, though recent literature has shown that the partisan divide has deepened so much that it seeks to draw higher education into its gaping maw, it is crucial that professional higher education lobbyists cultivate friendships in both partisan tribes (Burbridge, 2002).

Researchers have attempted to distinguish partisan views on higher education policy in what they see as two different philosophies on a crucial higher education issue: cost. According to Doyle (2007), Republicans in the U.S. Congress released a report in 2003 stating that the rise in college and university tuition could be directly attributed to bureaucratic inefficiencies on campuses, while Democrats laid the blame at the feet of state legislators diverting public resources away from higher education, leading the universities to increase tuition rather than cut services. Until recently, both parties viewed higher education as a sacred public good and held similar viewpoints on higher education policy (Doyle, 2007). Generally, Republicans want to make higher education institutions more accountable for how they spend taxpayer money and have published reports and authored bills to do so (Boehner & McKeon, 2003). Democrats, on the other hand, seem to be more concerned about how tuition increases affect the ability of different groups to access higher education, and they have introduced bills to require states to spend a certain portion of their budgets on higher education (S. Amendment 2725, 2014). While this previous research might help to highlight party and ideological divergences, it does not explain why conservative legislators seem to view college student lobbyists with disdain, nor does it address higher education policy or viewpoints at the state level, choosing instead to focus on federal representatives (Doyle, 2007). Also, Doyle’s (2007) work does not explore the views of “moderate” Republicans on higher education, a group that has regained legitimacy in Kansas politics (Berman, 2016).

A small body of research has focused on best lobbying practices for higher education, yet it makes no mention of using organized student groups to lobby in any capacity, much less meet with legislators directly. Murphy (2001) found that best practices for lobbying for increased higher education appropriations comprises a two-pronged approach. The first approach involves getting organized and developing a comprehensive state relations plan and a grassroots network of the legislators’ constituents who are alumni of the university and business groups in the legislators’ districts (Murphy, 2001). The second best-practice approach that Murphy (2001) advocated relates to researching and presenting the university’s economic impact in each legislative district, showcasing the jobs it has created and its overall fiscal impact. Ferrin (2005) described further strategies employed by higher education lobbyists, including contacting influential constituents who are alumni, engaging in letter-writing campaigns, publishing research results, and, in extreme cases, “open denunciation of opponents” (p. 182). It is also common for higher education lobbyists to mount inexpensive public relations campaigns through “beat” reporters assigned to cover their campuses (Ferrin, 2005). These strategies are employed in many states, including Kansas, where every dollar of public funds invested in higher education yields $11 in economic output (Kansas Board of Regents, 2011). However, as such strategies fail to curb funding cuts, higher education governmental relations professionals have begun appealing to students to serve as lobbyists in order to provide a fresh perspective and a human touch to efforts to increase funding.

As student lobbying for higher education issues continues its historic upward trend, there is a need to evaluate its effectiveness. Tankersley-Bankhead (2009) sought to measure student lobbyists’ impact on state-level higher education public policy by surveying students, professional higher education lobbyists, and legislators in Missouri. She found that students employed many of the same techniques as professional lobbyists, such as relationship-building and providing information on higher education policy. However, there is a need to expand the field of inquiry beyond Missouri to other states and focus on legislators’ perceptions of student lobbyists in order to determine their effectiveness.

A recent Pew Research Center study found that 58% of Republican voters had a negative view of higher education (Fingerhut, 2017). Similarly, in our study, Republican legislators who answered the survey were much more likely to view higher education as a private good, were more likely to have negative or neutral views of student lobbyists, and were much less likely to be influenced by a student’s lobbying efforts.

There are several divisive issues facing U.S. higher education institutions, and Kansas has been at the forefront of at least two of these issues, leading students from the public universities to come together around several shared interests. For instance, Kansas is not immune to the trend of accelerating decline in state appropriations for higher education. Since 2008, states have reduced higher education appropriations by an average of 23%, with Kansas facing a 22.8% reduction (Mitchell et al., 2015). College students in Kansas have an interest in reversing this trend. Although affordability is among the most pressing issues for Kansas college students, students formed and joined various interest groups to lobby the Kansas Legislature in reaction to the passage of concealed-carry legislation in 2017 (Kansas Legislature, 2017). This legislation allowed persons over the age of 21 to carry a weapon on campus without a permit or training, despite overwhelming disapproval from a majority of surveyed students and faculty (Cagle, 2017). Student groups mobilized to lobby the legislature to repeal this legislation, joining groups such as Moms Demand Action and Students Against Campus Carry, and forming the Kansas State Legislative Advocates group. Within the context of lobbying for these issues, this study came to be.

Adopting an interest-group theoretical framework and drawing on partisan views on higher education and higher education policy initiatives in the state of Kansas, this study sought to determine legislators’ perceptions of student interest groups. We use the term student lobbyist to refer to any student enrolled at a Kansas public higher education institution who calls, emails, or meets directly with a legislator in an effort to influence that legislator’s vote on an issue pertaining to higher education. In addition, a legislator is any one of the 125 members of the Kansas House of Representatives or the 40 members of the Kansas Senate.

Methodology

This study, which was approved by the Kansas State Institutional Review Board, set out to answer the following question: Are student lobbyists effective in influencing legislators’ decision making on matters of public higher education policy in Kansas? To address this question, we distributed a 20-question qualitative survey—designed to capture information regarding modes of student contact with legislators, perceived effectiveness of student lobbyists, and legislators’ perceptions of student lobbyists’ familiarity with public higher education policy issues—to all 165 elected officials when the state legislature reconvened on May 1, 2017. Reminder emails were sent every Monday while the legislature was in session. The responses were analyzed by the first author and synthesized, cross-referenced, and analyzed by both authors.

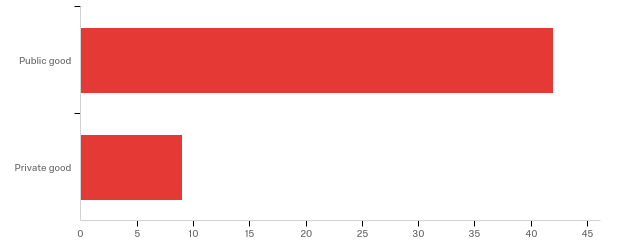

Of the 51 respondents to the survey, 47 completed the survey in its entirety. Thirty-eight respondents were Republicans, and 13 were Democrats. Twenty-nine were Republican House members, 10 House Democrats, nine Senate Republicans, and three Senate Democrats. Thirty respondents were graduates of Kansas Board of Regents (KBOR) public universities. Regarding respondents’ views on higher education, 82% saw higher education as a public good for Kansas, while 17% saw it as a private good (see Figure 1). One hundred percent of those respondents who saw higher education as a private good were Republicans; arguably, these individuals represented the most conservative survey respondents. The respondents were also confident in their own grasp of higher education issues in Kansas, with 95% indicating they were at least “moderately well informed” on such issues.

Figure 1

Perceptions of Higher Education in Kansas as a Public vs. Private Good

The 20 survey questions were categorized in five different sections, with each section a different variable (see Appendix). Questions 1–4 and 19 sought to identify the party affiliation of the respondents and their attendance at or exposure to KBOR schools, their overall perception of higher education in Kansas, and how well informed they believed themselves to be on higher education issues in Kansas. Questions 5–7 identified the frequency of contact between college students and legislators via email or phone, and/or in person. Questions 8–10, 15, 17, and 20 addressed the central focus of the study: the legislators’ perceptions of the student lobbyists, such as their respectfulness of alternative viewpoints, the degree to which they were informed on the issues, and whether the student being a constituent was likely to alter their opinion of the student. Questions 13, 14, 16, and 18 had the strongest implications for future practice, as they sought to evaluate the effectiveness of the student lobbyists, asking if the legislator had ever altered their opinion or changed their vote based on testimony from a student lobbyist, and comparing the effectiveness of higher education governmental relations professionals to that of student lobbyists. Lastly, Questions 21 and 22 were purely qualitative, asking the legislators to share positive and negative interactions with student lobbyists.

Discussion of Findings

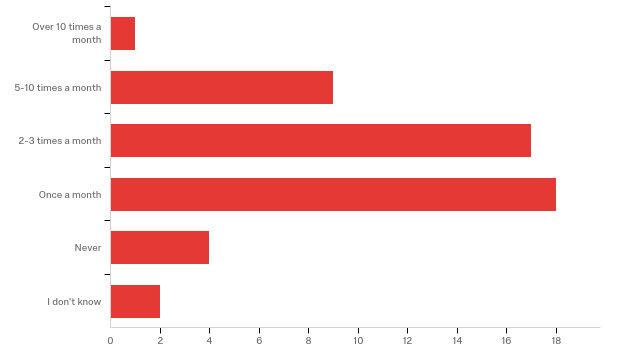

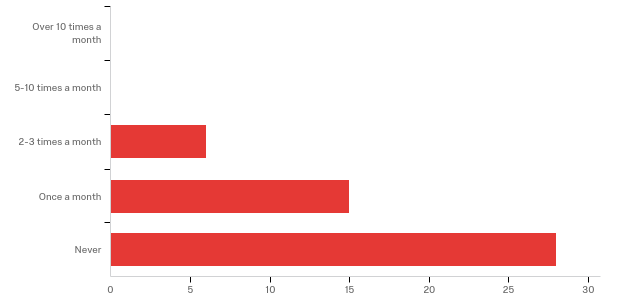

Adhering to our definition of student lobbyists for this study, interaction with legislators was not limited to organized efforts; college students who took it upon themselves to contact a legislator to give testimony or lobby that legislator in person, by email, or by phone were considered lobbyists. Therefore, one variable we addressed was the frequency of contact with students. The study data showed that students were more likely to email a legislator, and more frequently, than call them (see Figures 2 and 3). In fact, no student lobbyist contacted a legislator by phone more than three times a month (see Figure 3).

Figure 2

Frequency of Contact With Students by Email

Figure 3

Frequency of Contact With Students by Phone

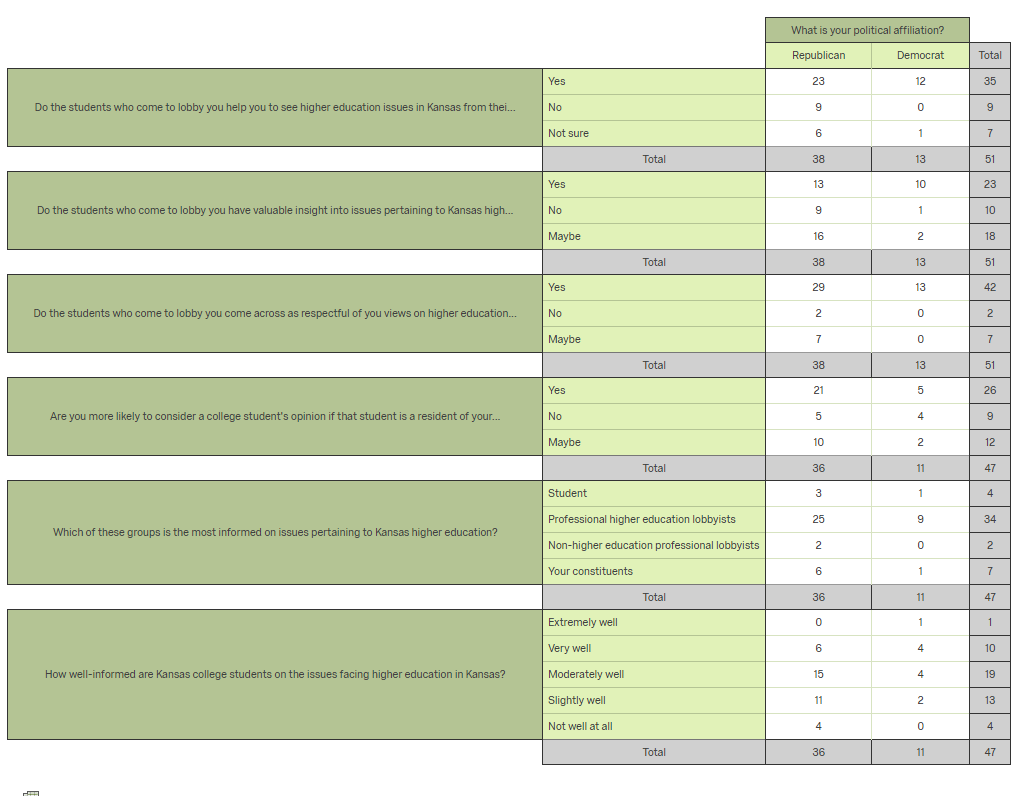

When we analyzed the data related to legislators’ perceptions of the student lobbyists themselves, the partisan divide reared its head. Asked if the students who contacted them helped the legislators see issues from the students’ viewpoint, nine of the 51 Republicans answered “No,” while all but one Democrat answered “Yes” (see Figure 4). By this metric, students were much more effective at evoking empathy from Democrats than Republicans. When legislators were asked if the students who lobbied them possessed valuable insight into the issues facing Kansas higher education, the results were more mixed (see Figure 4). Again, students were more likely to have insights that resonated more with Democrats; though 16 Republicans answered “Maybe,” nine Republicans answered flatly, “No.” The third question in this section of the survey assumed that some Republicans would view college students as disrespectful of their views on higher education. While the variance in opinions on this question was an entirely Republican one—all 13 Democrat respondents answered in the affirmative—29 of the Republicans also answered in the affirmative (see Figure 4); only two Republicans answered “No,” and seven answered “Maybe.” Democrats were also much more likely to agree that student lobbyists were more informed on the issues. Nine out of 11 Democrats said students were “moderately,” “very,” or “extremely” well informed. Conversely, 15 Republicans saw the student lobbyists as “moderately well-informed,” 11 viewed them as “slightly well-informed,” and four perceived the students as “not well informed at all.” This partisan disconnect is troubling, as it mirrors the Pew data suggesting strongly that Republicans are more likely to have hostile views of higher education (Fingerhut, 2017).

Figure 4

Partisan Perceptions of Student Lobbyists

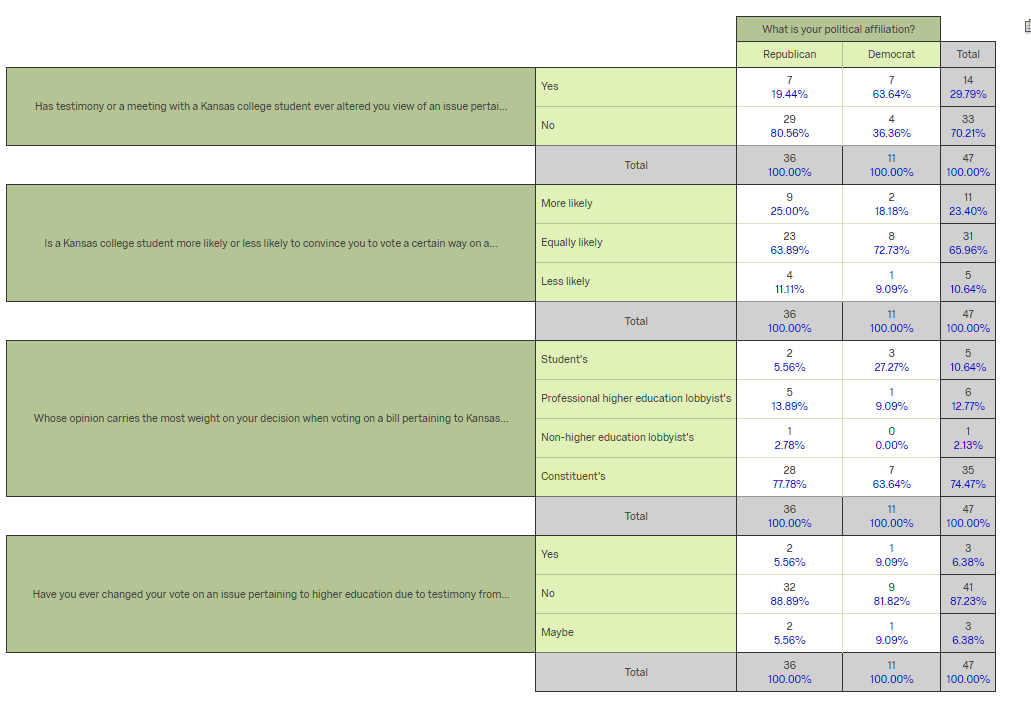

When evaluating the effectiveness of the student lobbyists through the lens of outcomes—that is, influencing legislators to change their votes or alter their views on higher education issues, or to simply be seen as a legitimate lobbying force alongside professional higher education lobbyists—the results were disconcerting. An alarming 70% of legislators (29 of 36 of Republicans, versus four of 11 Democrats) said that a meeting with a college student lobbyist had never altered their view on an issue (see Figure 5). Though there was still a partisan slant to this data point, perhaps most interestingly, there was little partisan difference in the effectiveness of student lobbyists in changing votes. A total of 87% of the respondents—88% of Republicans and 81% of Democrats—indicated that they had never changed their vote on an issue based on the testimony of a college student (Figure 5). If the central goal of lobbying is to change minds on an issue (e.g., whether to cast a vote in favor of allowing guns on campus), then the student lobbyists in Kansas have suffered (and are suffering) a resounding defeat. However, all is not lost for these student advocates. Sixty-six percent of the respondents (64% of Republicans and 73% of Democrats) said they were “equally likely” to consider the opinion of students as the opinion of professional higher education lobbyists when voting on an issue (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Partisan Perceived Effectiveness of Student Lobbyists

Such results highlight the challenges Kansas college students face in establishing themselves as a legitimate interest group commanding the attention and respect of many legislators. Other factions, such as professional higher education lobbyists, have the legislative clout to effect policy change and are therefore perceived as worthier of interest group status. While students have a legitimate interest in many policy issues that affect their campuses, the survey results send a clear message that they have not melded their interests into a faction that commands influence. Arguably, this is reflected in the lack of literature on students as lobbyists or advocates in public policy.

Much work remains for these students, and building bridges with legislators—namely more conservative legislators—should be of primary importance for student lobbyists and the higher education governmental relations professionals who advise them. The data gathered from this survey did not paint a particularly rosy picture; yet, considering that using students as effective lobbying tools is still a relatively new concept, there are few precedents. Creativity and innovation are needed, and what better environment for creativity and innovation than a college campus?

Implications for Practice

The results of this study will help public higher education interest groups, such as higher education lobbyists, student governing associations, and higher education administrators, to better understand legislators’ perceptions of student lobbyists, more effectively train and prepare student lobbyists, and/or revise their lobbying strategies. This study also has implications for governmental relations or student interest groups seeking to more successfully engage and lobby members of their state legislatures. In times of constrained budgets, public higher education institutions should be looking for the most efficient ways to leverage their greatest resources: the students themselves.

More effective student lobbyists would likely translate to more votes in favor of increased resources for higher education, leading to reduced tuition and addressing socioeconomic inequity in higher education. With continued divestment of public funds for higher education in states that have factions of legislators that increasingly see higher education as a private good, the findings of this study will benefit students and lobbying professionals in many states.

Since the aim of this study was to inform higher education governmental relations practice, it is appropriate to analyze the data’s implications for college student lobbyists and higher education governmental relations professionals. Previous literature has indicated that Republicans are adopting increasingly negative views of higher education, and the data gathered in this study reflect this finding. Conservative Republicans in the Kansas Legislature are more likely to view higher education as a private good, primarily benefitting the individual graduate, not the state as a whole. Conservatives are also more likely to listen to the counsel of professional lobbyists than students, have negative views of student lobbyists, and view students as not well-informed or uninformed about the issues, or not respectful of opposing views regarding issues facing Kansas higher education.

Finding alternative ways to reach conservatives would be a key component to more successful student lobbying outcomes. The literature around higher education and politics has supported this since conservatives control most state legislatures and are the prevailing force behind budget cuts to higher education, including in Kansas (Seltzer, 2016). The onus for altering these perceptions is on students and on higher education governmental relations professionals, who must put more effort into training student lobbyists, supplying them with information that will get through to conservatives (e.g., the economic impact universities have in their districts, the number of graduates in their districts, etc.), and being seen with students in order to give them more legitimacy. Some of the “soft skills” that professional lobbyists possess—such as the ability to tolerate opposing views, engage in respectful debate, eloquently express their point of view, and frame the narrative of their cause using concrete evidence—would be a logical focus in the training of student lobbyists. Making progress with this training could go a long way toward making inroads with the conservative factions of the Kansas Legislature, as supported by this study’s survey results. Additionally, a “debate camp” prior to any visit to the capitol could help introduce students to views held by legislators and also reinforce the need to be respectful, to give legislators their undivided attention, and to rehearse their “pitch” for more funding. A “practice run” like this could give student lobbyists a more realistic glimpse of the lobbying profession, fostering an appreciation for how difficult their task is.

The assertion that constituents of legislators’ districts are the most effective voices in policymaking was supported by our study findings. Drawing on the finding that legislators were much more likely to consider a student’s opinion on an issue if the student was a resident of the legislator’s district, we recommend that, when assigning legislators for students to talk to, efforts should be made to match constituents with their legislators. Not only will this help build a relationship between the student and the legislator, but it will also show the legislator that residents of their district care about higher education funding; potentially, this will be in their mind when they cast a vote. This also brings into account that the majority of legislators of both parties are the most likely to consider the views of their constituents over the views of students or professional lobbyists (who are not constituents). Therefore, a matching program would be effective when preparing for higher education lobbying efforts.

Lastly, as the study findings suggest, legislators from both parties see higher education governmental relations professionals as more informed on issues than students. Therefore, these professionals should lend their expertise and legitimacy to student lobbyists. Given that higher education governmental relations professionals devote considerable time and resource to building relationships with legislators, these professionals should consider helping the students they advise build similar relationships and gain greater legitimacy in the eyes of legislators. The qualitative answers to the study survey showed that many legislators wanted the students to be successful, and many had been continually impressed with the performance and conduct of the student lobbyists.

One legislator said, “I have met with numerous college students during the session and they have made a very positive impression on me.” Another legislator stated, “All interactions have been positive and respectful.” Building upon such positive impressions is paramount to the successful lobbying outcomes of students. Perception is critical when building a new program in the public sphere. If student lobbyists are not perceived as legitimate interest groups, they stand little chance of success.

Limitations of the Study

As with many qualitative surveys, the number of responses in this study was relatively small, though our survey did achieve a response rate of 31%, which, according to the Kansas State University Director of Government Relations, is well above average (S. Peterson, personal communication, April 28, 2017). Additionally, many members of the Kansas Legislature who did not respond could have provided a starker contrast between the parties on perceptions of student lobbyists and offered more qualitative testimony on their interactions with student lobbyists.

In our nuanced political society, “Republican” and “Democrat” are not neat identifiers of ideology. Lest we dissuade respondents from completing the survey, we did not use more specific identifiers such as “moderate Republican,” “fiscal conservative,” or “progressive vs. moderate Democrat.” In particular, the “moderate” or “centrist” Republican faction in Kansas muddied the results concerning partisan views since these Republicans are overwhelmingly in favor of increased public funding for higher education and are much more likely to view students as effective advocates for their universities.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

To enhance the success of future higher education lobbying efforts, it is vital that researchers continue to explore the reasons conservatives distrust higher education and continue to view it as a solely private good. Demanding fiscal accountability and good stewardship of public funds is a major reason why conservatives do not trust higher education; however, this does not explain why they choose to ignore higher education’s public benefits, with graduates earning more, creating jobs, and conducting research in STEM, agriculture, and other areas that produce immeasurable economic output in their legislative districts. An inquiry into the growing number of conservatives who do not focus on such public goods is worth exploring.

Because students are a relatively new resource in higher education lobbying—and likely not one to fade any time soon—more research should be conducted on how involvement in the political process through lobbying helps students develop into informed and engaged members of civic life. The field of student development theory could be augmented significantly by a theory of student political identity development that complements sexual identity, racial identity, and social identity development.

In addition, since this study was limited to Kansas, further studies should be conducted in other states. The perceptions of student lobbyists in other states might vary greatly, especially in states with well-established and vocal student populations. Iowa State University, for instance, has a longstanding Alliance for Iowa State program (http://alliance.isualum.org/) through which university stakeholders, including students, lobby the legislature around a slate of issues pertinent to the university. The Legislative Advocates program at Kansas State University (https://www.k-state.edu/sga/executive/legislative-advocates/index.html), of which the first author serves as chair, was modeled after the Alliance for Iowa State. Tennessee, with its deep-red political leanings and well-established place as a leader in higher education innovation, would be a noteworthy case study in its use of student lobbyists. The political climate of Kansas is unique, and the results of this study should by no means be used to generalize the perceptions of student lobbyists in other states, especially more diverse and more Democratic states.

Additionally, higher education governmental relations professionals should be surveyed in order to capture their perceptions of student lobbyists and how effective the students are in achieving their lobbying outcomes. Conventional wisdom states that student testimony on how budget cuts affect their lives is an effective tool for lobbying, but perhaps, in the end, students are not the most effective “vehicle” for delivering that testimony. The results of a broad survey could help revise lobbying best practices for higher education governmental relations professionals.

Conclusion

Student lobbyists have seemingly been unable to change the minds, and by extension, the votes of legislators on higher education public policy issues in Kansas. These students are perceived by many conservative legislators as being uninformed on issues, disrespectful of opposing views, unable to add value to their conversations, and less informed on issues than professional higher education lobbyists. As one presumably ultra-conservative legislator said, in a particularly negative tone:

Students have an idealist viewpoint that may not reflect my district constituents’ values. Liberal professors have too much influence on basic values instilled by parents and family. That aspect makes me not want to send kids off to be brainwashed on liberal doctrine.

This was not an isolated comment. Today, student lobbyists and higher education governmental relations professionals must not only contend with declining funds, but also legislators who are hostile to the very idea of higher education, despite the evidence that it is an undeniable public good for their districts.

More positively, several of the survey respondents did see higher education as a public good, viewed the students as respectful of their opinions, and used adjectives like “genuine,” “passionate,” and “rational” to describe the students. A majority of Democrats held the student lobbyists in high regard on all metrics, except for altering their views or changing their votes. Using these data to inform their practice moving forward, student interest groups in Kansas can reevaluate their lobbying strategies, become more prepared in their interactions with legislators, and seek help, training, and legitimacy from professional lobbyists.

Many in the public sphere and in political circles lament that college students are not more involved in the policymaking process. Investing in higher education and curbing the growth of student debt is an unprecedented issue impacting millennials and now Generation Z. Getting students civically involved on their campuses, harnessing their passion and their frustration with elected officials, and ultimately helping legislators see the societal benefits of higher education as a worthwhile investment is a new and innovative approach for higher education governmental relations professionals to pursue. Actively involving college students in lobbying for higher education will hopefully yield dividends in the form of greater social equality, reduced student debt, higher middle-class wages, and, ultimately, a healthier democracy.

References

Benveniste, G. (1985). New politics of higher education: Hidden and complex. Higher Education, 14(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00137483

Berman, R. (2016, August 4). Moderates sweep Kansas primaries in backlash against Brownback. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/08/kansas-republicans-rebuke-their-conservative-governor-brownback/494405/

Blumberg, R. L. (1991). Civil rights: The 1960s freedom struggle. Twayne Publishers.

Boehner, J. A., & McKeon, H. P. (2003). The college cost crisis: A congressional analysis of college costs and implications for America’s higher education system. U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce & U.S. House Subcommittee on 21st Century Competitiveness.

Burbridge, L. C. (2002). The impact of political variables on state education policy: An exploration. Journal of Education Finance, 28(2), 235–259.

Burgess, B., & Miller, M. T. (2009). Lobbying behaviors of higher education institutions: Structures, attempts, and success. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504427.pdf

Byrd, R. C. (2006). History of lobbying: An essay by Senator Robert C. Byrd. Congressional Digest, 85(5), 130–160.

Cagle, E. (2017, June 30) Kansas universities, students express preparedness for guns on campus starting Saturday. Kansas City Star. http://www.kansascity.com/news/politics-government/article159193599.html

Cigler, A. J., & Loomis, B. A. (Eds.). (2011). Interest group politics (7th ed.). Sage.

Cook, C. E., & McLendon, M. K. (1998). Challenges in the early 1990s. In C. E. Cook (Ed.), Lobbying for higher education: How colleges and universities influence federal policy (pp. 34–52). Vanderbilt University Press.

Doyle, W. R. (2007). Public opinion, partisan identification, and higher education policy. The Journal of Higher Education, 78(4), 369–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2007.11772321

Ferrin, S. E. (2005). Tasks and strategies of in-house lobbyists in American colleges and universities. International Journal of Educational Advancement, 5(2), 180–191.

Fingerhut, H. (2017). Republicans skeptical of colleges’ impact on U.S., but most see benefits for workforce preparation. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/07/20/republicans-skeptical-of-colleges-impact-on-u-s-but-most-see-benefits-for-workforce-preparation/

Flacks, R. (1967). The liberated generation: An exploration of the roots of student protest. Journal of Social Issues, 23(3), 52–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1967.tb00586.x

Kansas Board of Regents. (2011). The impact of the Kansas Board of Regents system to the state’s economy. https://www.kansasregents.org/resources/PDF/1172-KBORSystemEconomicImpactStudy.pdf

Kansas Legislature. (2017). 2017 statute. http://www.kslegislature.org/li_2018/b2017_18/statute/075_000_0000_chapter/075_007c_0000_article/075_007c_0003_section/075_007c_0003_k/

Longo, N. V. (2004). The new student politics: Listening to the political voice of students. Journal of Public Affairs, 7, 61–74.

Lowery, D. (2007). Why do organized interests lobby? A multi-goal, multi-context theory of lobbying. Polity, 39(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.polity.2300077

Mitchell, M., Palacios, V., & Leachman, M. (2015). States are still funding higher education below pre-recession levels. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/states-are-still-funding-higher-education-below-pre-recession-levels

Murphy, E. P. (2001). Effective lobbying strategies for higher education in state legislatures as perceived by government relations officers [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Louisiana State University.

Potter, W. (2003, April 25). Citizen lobbyists. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 49(33), A24–A25.

S. Amdt. 2725 to S. Cong. Res. 95, 108 Cong. (2003–2004). (2004, March 10). https://www.congress.gov/amendment/108th-congress/senate-amendment/2725/all-info

Seltzer, R. (2016, May 23). Kansas cuts criticized for harming large research universities. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/05/23/kansas-cuts-criticized-hurting-large-research-universities

Swanstrom, R. (1988). The United States Senate, 1787-1801: A dissertation on the first fourteen years of the upper legislative body (No. 13614). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Tandberg, D. A. (2010). Politics, interest groups and state funding of public higher education. Research in Higher Education, 51(5), 416–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9164-5

Tankersley-Bankhead, E. (2009). Student lobbyists’ behavior and its perceived influence onstate-level public higher education legislation: A case study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Missouri, Columbia.

Thomas, C. S., & Hrebenar, R. J. (2004). Interest groups in the States. In V. Gray & R. L. Hanson (Eds.), Politics in the American States: A comparative analysis (8th ed., pp. 100–128). CQ Press.

Appendix: Legislator Survey

|

What is your political affiliation?

Which chamber of the Legislature are you a part of?

Are you a graduate of a Kansas Board of Regents university (Washburn, Fort Hays, Pittsburg, Wichita State, Emporia State, Kansas State or the University of Kansas)?

Do you see higher education in the state of Kansas as a public good (benefits all of Kansas) or a private good (primarily benefits the individual graduate)?

How often do Kansas college students email you to try to influence your vote on an issue pertaining to higher education?

How often do Kansas college students call you to try to influence your vote on an issue pertaining to higher education?

Have you ever had a Kansas college student meet you in your legislative office to try to lobby you on an issue?

Do the students who come to lobby you come across as respectful of your views on higher education?

Do the students who come to lobby you have valuable insight into issues pertaining to Kansas higher education?

Do the students who come to lobby you help you to see higher education issues in Kansas from their point of view?

Has testimony or a meeting with a Kansas college student ever altered your view of an issue pertaining to higher education?

Is a Kansas college student more likely or less likely to convince you to vote a certain way on a higher education bill than a professional higher education lobbyist?

Are you more likely to consider the opinion of a student who comes to lobby you if that student is a resident of your district?

Whose opinion carries the most weight on your decision when voting on a bill pertaining to Kansas higher education?

Which of these groups is the most informed on Kansas higher education issues?

Have you ever changed your vote on an issue pertaining to higher education due to testimony from or a meeting with a Kansas college student?

How well-informed are you regarding the issues facing higher education in Kansas?

How well-informed are Kansas college students regarding the issues facing higher education in Kansas?

Describe a positive experience you’ve had as a legislator when meeting with a college student who is trying to lobby you (if any).

Describe a negative experience you’ve had as a legislator when meeting with a college student who is trying to lobby you (if any).

|

Authors

James J. Krotz is a senior academic and career advisor in the College of Agriculture at Purdue University. James is an alumnus of Kansas State University, where he founded a student lobbying organization, interned in the Kansas Legislature, and worked on several political campaigns. James is the recipient of the 2018 Tony Jurich Community Commitment and Leadership Award and is active in NACADA: The Global Community for Academic Advising.

James J. Krotz is a senior academic and career advisor in the College of Agriculture at Purdue University. James is an alumnus of Kansas State University, where he founded a student lobbying organization, interned in the Kansas Legislature, and worked on several political campaigns. James is the recipient of the 2018 Tony Jurich Community Commitment and Leadership Award and is active in NACADA: The Global Community for Academic Advising.

Dr. Lisa M. Rubin is an associate professor in the College of Education at Kansas State University. She serves as co-editor of the NACADA Journal. Dr. Rubin is a recipient of the National Association of Academic and Student-Athlete Development Professionals (N4A) 2020 Research Award, the 2019 Professional Excellence Award, and the 2009 Professional Promise Award. She received the Big 12 Faculty Fellowship and the NCAA Innovations in Research and Practice Grant in 2018. In 2017, she was named one of the Top 25 Woman Leaders in Higher Education and Beyond by Diverse: Issues in Higher Education.

Dr. Lisa M. Rubin is an associate professor in the College of Education at Kansas State University. She serves as co-editor of the NACADA Journal. Dr. Rubin is a recipient of the National Association of Academic and Student-Athlete Development Professionals (N4A) 2020 Research Award, the 2019 Professional Excellence Award, and the 2009 Professional Promise Award. She received the Big 12 Faculty Fellowship and the NCAA Innovations in Research and Practice Grant in 2018. In 2017, she was named one of the Top 25 Woman Leaders in Higher Education and Beyond by Diverse: Issues in Higher Education.