By Adrienne M. Hooker, David M. Wang & Carol-lynn Swol | Contemporary methodologies of art and design pedagogy offer ways to address pressing societal issues and to improve civic knowledge through purposeful inquiry and action. The creative energy inherent to art and design allows faculty to open dialogues, foster ambiguity, and deepen content for undergraduate students through a number of approaches—from project-based learning in foundation courses to community-based research in capstone experiences. This article details a creativity model comprising actionable methods for bringing civic consciousness into the classroom by aligning best practices from art and design pedagogy with the concepts and nomenclature of civic learning and democratic engagement to critically address broader issues. By examining selected case studies, the authors demonstrate that creative energy is a necessary component to applying civic skills and enabling collective action throughout a student’s undergraduate education. Educational experiences that allow students to follow their curiosity and explore ambiguity in an effort to address wicked problems in their coursework, such as food insecurity, can have lifelong value.

Author Note

Adrienne M. Hooker, School of Media Arts and Design, James Madison University; David M. Wang, School of Media Arts and Design, James Madison University; Carol-lynn Swol, Civic Learning and Democracy Initiatives, Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Adrienne M. Hooker, Assistant Professor, School of Media Arts and Design, James Madison University, MSC 2104, 54 Bluestone Drive, Harrisonburg, VA 22807. E-mail: hookeram@jmu.edu

The pedagogy of art and design compels students to engage with society. For artists and designers, expertise is rooted in the creative process and studio practice, which inherently foster a civic dimension for making choices about message, materials, and craftsmanship. The act of creation provides a way to reflect on and express compelling ideas with greater social impact, ultimately encouraging artists and designers to share ideas beyond themselves.

Historically, the study of art and design includes not only a rich cultural heritage tied to the art of production, but also activities that have inspired countercultural movements and socioeconomic revolution. Artists and designers have been central to instigating social change throughout history, ranging from the political propaganda of the Russian Revolution (Heller, 2017) and World War II (Little, 2016) to current artists reflecting upon and challenging established norms of location, religion, and race. Within cultures, artists and designers have visually addressed wicked problems to elevate issues for the world to ponder through unexpected perspectives. According to Kolko (2012),a wicked problem is a social or cultural problem that is difficult or impossible to solve for as many as four reasons: incomplete or contradictory knowledge, the number of people and opinions involved, the large economic burden, and the interconnected nature of these problems with other problems.

Recent examples related to gender roles have been brought to the forefront in works by the Guerrilla Girls (see https://www.guerrillagirls.com) and Barbara Kruger (Forster, 2018), while the works of Kara Walker (see http://www.karawalkerstudio.com) and Titus Kaphar (National Portrait Gallery, n.d.) have addressed racism. Indeed, there is much to be gained by viewers when artists visually explore societal issues; for instance, Banksy’s subversive epigrams provoke the viewing public to discuss, debate, and even censor uncomfortable visuals (see http://www.banksy.co.uk). Likewise, higher education faculty—not only in art and design programs, but across multiple disciplines—can advance civic knowledge and collective action when they consider the value of creative energy in addressing wicked problems within the classroom.

For undergraduate students with a personal motivation to explore topics around community awareness and to respond to wicked problems, it is necessary to build a shared vocabulary that connects creative thinking with initiatives in civic engagement. Art and design faculty regularly require students to craft visual messages, master technical skills, and participate in dialogues in an effort to explore ideas and share feedback necessary to refining their work (Costantino, 2015). However, not all faculty in art and design encourage students to investigate the motivations behind aesthetics or to discuss social issues; rather, many tend to focus solely on visual composition. The world, and today’s students, demand more than technical skills for education. Thus, faculty should critically address broader issues by including a more diverse range of core values within individual competencies. Creative energy is a necessary component to applying civic skills and encouraging collective action throughout students’ education in undergraduate degree programs.

In this article, we highlight correlations between studio/design course activities and practices that foster the development of a civic lens in curricula. To help reveal connections between such practices and civic engagement, we classified the categories of civic knowledge, skills, values and action items—found within A Crucible Moment (National Task Force, 2012) and in the blog series for the “Emergent Theory of Change” (Hoffman, Domagal-Goldman, King, & Robinson, 2018)—into three creative-energy methods common to project-based art and design courses: content, dialogue, and ambiguity. Aligning social impact outcomes from art and design curricula with the established and emerging skills and values of civic learning illustrates pedagogical and conceptual connections for civically engaged faculty. These concepts, distilled into the creativity model discussed here, can guide faculty across disciplines.

Table 1 offers a visualization of how dialogue, one of the three creative-energy methods, correlates with specific civic-engagement terms. For example, when comparing the civic knowledge of diverse belief systems (from A Crucible Moment) to the Emergent Theory of Change’s ideas of dignity and humanity, we found that many of these values and actions are regularly practiced in art and design courses in which faculty encourage students to provide feedback on work from the maker’s perspective rather than their own. Further investigation into the civic knowledge and skills outlined in A Crucible Moment and the civic values and collective actions of both A Crucible Moment and the Emergent Theory of Change revealed that these concepts align with the creative energy method of iterative dialogue.

Table 1

Comparison of Iterative Dialogue within Art and Design Courses to Theories in A Crucible Moment and Emergent Theory of Change

|

Creative Energy Methods |

Civic Knowledge |

Civic Skills |

Values and Collective Action |

Art and Design Project-Based Course |

|

|

A Crucible Moment |

A Crucible Moment |

Emergent Theory of Change |

|||

|

Iterative Dialogue |

Exposure to multiple belief systems and to alternative views about the relation between beliefs and government |

Respect for freedom and human dignity |

Dignity—respect for the intrinsic moral equality of all persons |

In a project-based studio course students are encouraged to provide feedback on the work created by classmates from the maker’s perspective, rather than what one would do differently if they were the designers or makers. Assisting a colleague to make their project better encourages honoring the dignity of the other person and their concepts—regardless of message agreement. |

|

|

Gathering and evaluating multiple sources of evidence |

Empathy and Equality |

Humanity—embracing environments and interactions that are generative and organic; rejecting objectification, and the marginalization of people based on aspects of their identities |

|||

|

Seeking, engaging, and being informed by multiple perspectives |

Ethical Integrity |

Decency—acting with humility and graciousness; rejecting domination for its own sake |

During formal critique students are encouraged to share their feedback with decency and respect. |

||

|

Deliberation and bridge building across differences |

Compromise, civility, and mutual respect |

Honesty—frankness with civility; congruence between stated values and actions; avoidance of deceit, evasions, and manipulative conduct |

Honest and open sharing is a near constant practice in the project-based course. Students are encouraged to be honest and kind (civil) during open studio and lab hours when students are working without faculty supervision. |

||

|

Collaborative decision making |

Moral Discernment and behavior |

Participation—action with other people to develop and achieve shared visions of the common good |

Students in an art and design project-based course learn to address a concept or problem within the assigned project parameters. Sometimes the assignment is more directive and sometimes less so. Students working in service learning or community engaged projects have the added opportunity to work on resolving problems with a partner. |

||

|

Ability to communicate in multiple languages as well as formats |

Public problem solving with diverse partners |

Resourcefulness—capacity to improvise, seek and gain knowledge, solve problems, and develop productive public relationships and partnerships |

|||

Iterative dialogue can have many meanings. The focus of this creative-energy method is to establish a sustaining role—that is, a role that is supportive and constructive—to question and provide feedback about a proposed solution. Students in art and design courses are taught to work actively with each other to develop each individual’s solution to a concept. Students learn expectations for appropriate classroom behavior from their faculty, both through course syllabus guidelines and from the manner in which the professor facilitates discussions, which ideally model the civic values highlighted in A Crucible Moment and the Emergent Theory of Change. These values are intrinsic to the constructive critical analysis used regularly within iterative dialogue. Though these civic values and actions already exist within art and design classrooms, this method of focusing creative energy could also be applied to non-art courses.

The correlation of similar theories helps harmonize the many related schools of thought among diverse academic communities. Civic learning and democratic engagement practitioners use the civic value-related terms mentioned previously, whereas art and design programs employ parallel concepts such as social impact and design for good (Cooper-Hewitt 2013). However, the differing rhetoric should not dissuade anyone from participating in civic practices of engagement with students in the classroom. Instead, the use of varied vocabulary should stimulate a more holistic approach to curricula for all faculty and students.

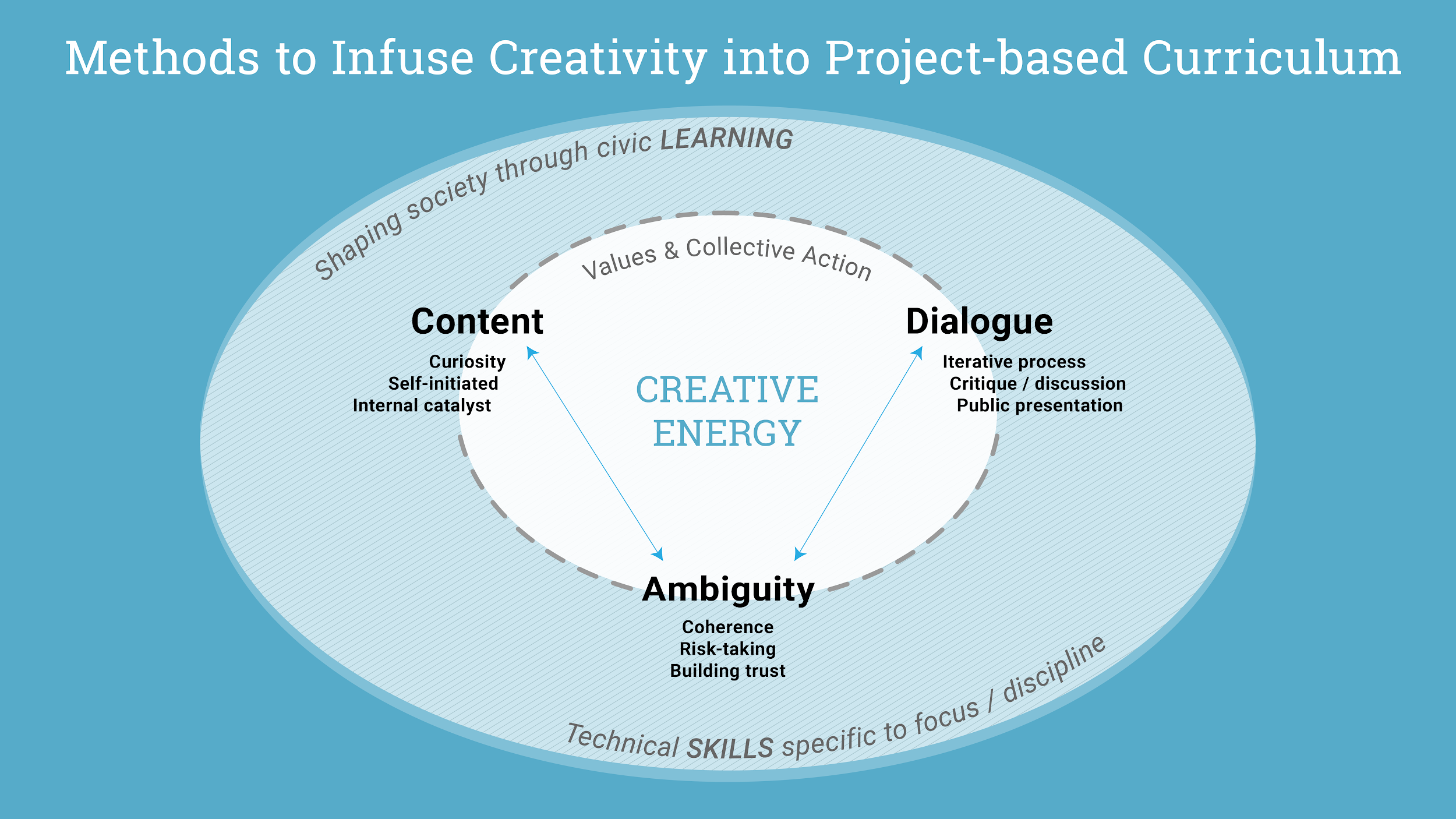

To further investigate how best practices in art and design curricula can help address society’s wicked problems, Figure 1 illustrates how self-initiated content and iterative dialogue foster ambiguity. The model, which was introduced in a workshop at the 2018 Civic Learning and Democracy Engagement meeting and highlighted in the “Creativity-Infused Pedagogy to Foster a Civic Consciousness” feature in the fall 2018 Bringing Theory to Practice Newsletter (Swol, 2018), infuses creativity into project-based courses, allowing students to practice civic values and actions within the process itself.

Figure 1. Methods for infusing creativity into project-based curricula.

This creativity model fosters civic learning and democratic engagement on two levels—within the classroom to encourage the next generation of democratic citizens and in collaboration with community partners to improve the quality of pluralistic society. The model is used in coordination with the disciplinary skills and knowledge necessary to meet course goals and fulfill assignments. When the creativity model is implemented through a scaffolded approach, foundation-level students can test concepts and apply skills within the safety of a training ground, then gradually expand their abilities as they complete higher-level courses. Moreover, after graduation, a civically motivated student can continue to practice the model using their increased expertise in projects to improve democracy and help solve the world’s wicked problems.

A creativity-infused project built on the three pillars of content, dialogue, and ambiguity begins with the selection of content. The method of including self-initiated projects allows students to discover topics through their natural curiosity and to nurture and drive their critical thinking and inventive problem solving. When given even a small amount of freedom of choice within the context of a course, students will have increased buy-in and will ultimately be open to taking bigger risks and pushing conceptual ideas further. Research has shown the importance of self-determination for enhancing learning and improving life skills. Students who are intrinsically motivated (i.e., choosing the content of the project) sustain creativity and efforts in solving issues (American Psychological Association, 2004).

Beyond self-initiated content, the creativity model also promotes civic values through the process of iterative dialogue. As previously mentioned, each student is consistently engaged in dialogue with their classmates to understand how others interpret their project and to understand other students’ projects from the maker’s perspective. This interaction, within peer-to-peer and larger groups, emphasizes and brings into practice empathy, civility, and dignity. Repeated discussions during the development of a project are essential to improving the work and to building the courage to present it publicly.

Both creative thinking and constructive dialogue facilitate a space for ambiguity within a project-based course (Constantino, 2015)—the final pillar of the creativity model which allows civic values to blossom. All participants, students and faculty alike, must grapple with issues that develop spontaneously. If handled with decency and honesty, this ambiguity can build a stronger sense of trust within the group and provide latitude in taking risks. It is the responsibility of faculty to bring coherence to the dynamic in order for students to be comfortable contributing to the class and to each other’s projects.

Case Studies

The following case studies represent a programmatic progression from a foundation-level course to an interdisciplinary capstone experience, illustrating how undergraduate students can use dialogue and build trust to help grapple with ambiguity in a media-arts and design-degree program.

The ideas of self-selection, discussion, and ambiguity are familiar to art and design programs as well as graduate studies; however, we propose that this creativity model should be incorporated within undergraduate curricula spanning the vast array of disciplines. Students in all majors should be encouraged to participate in civic inquiry and to practice civic values within as many courses as possible. When students are asked to use the creativity model in a variety of subjects, they have the opportunity to practice solving wicked problems in many contexts. This enhances their ability to think critically through larger, more complex issues by practicing inquiry-based learning.

Only with this pedagogical coherence from foundation to capstone will students gain the knowledge, capacity, and foresight to tackle problems outside the classroom. Each faculty member can evaluate how to incorporate small aspects of the creativity model within their individual course projects and discuss with colleagues within their discipline how to bring civic inquiry and values to their major curriculum, from foundation to capstone.

Case Study 1: Foundation Level

Within James Madison University’s (JMU’s) School of Media Arts and Design (SMAD), faculty have begun incorporating the creativity model within individual courses. Colleagues have also begun conversations about how to continue civic inquiry and values across curricula so students develop a sense of social responsibility within their narrative media work. One such project adhering to the creativity model is used in the first author’s foundation-level visual communication course, “SMAD 201: Foundations in Visual Communication.” Once students are accepted into the media arts and design major, usually in their sophomore year, SMAD 201 sets the stage for building their civic capacity throughout the major. Each semester, the 40 to 80 students enrolled in this required entry-level course not only address topics of social importance in their own work at their level of expertise, but they also critique and revise major projects with their peers through iterative dialogue. Because this course represents the beginning of students’ visual communication education, their knowledge/content and technical skill levels will likely increase across successive assignments within the course and further develop within the major. Additionally, the process of constant peer-to-peer discussion around the developing projects creates an environment of trust and exploration, building a space that reinforces feelings of belonging and promotes autonomy and self-expression.

At the end of the 15-week course, the culminating project demonstrates their newly acquired technical skills and requires them to consider how these competencies might assist a local nonprofit in its mission. Students must self-select an organization to research and then develop a meaningful call-to-action campaign. The project parameters require that concepts related to certain deliverables be linked using consistent messages and visuals; however, each student must decide what societal issue will be addressed through their campaign.

Each student is asked to frame their issue by selecting and researching a community agency as a “client”; however, they are not required to work with the nonprofit directly. This allows conceptual exploration of a topic without the impediment of client personal preferences or budgetary constraints. At the foundation level, students in general are not fully prepared to work with community partners due to their lack of confidence in technical skills and/or communication. The project is therefore a prime opportunity for students to self-determine their content, practice iterative dialogue skills, and learn to embrace working with ambiguity without fully executing the final product—essentially working within a training ground to nurture student confidence. It is the first step in a scaffolded approach to the creativity model within the context of civically engaged projects. Students can engage and grapple with ideas while thinking critically about solutions to wicked problems within the safety of the creativity-infused classroom. If scaffolded properly, this model can prepare students who are advancing to intermediate and capstone courses to work confidently with community partners and to share concepts and products for real-world implementation.

One such student who engaged in this foundation-level call-to-action campaign chose food insecurity as her topic and selected the newly formed student organization Campus Kitchen as the nonprofit to research and on which to base her concepts. She developed an awareness campaign around fighting hunger on campus and within the local community by reducing the amount of food waste created. Specifically, through iterative dialogue with classmates, the student developed and refined a final call-to-action campaign targeting college students to engage in fighting food waste on campus. She created concepts for a poster designed to recruit members to join the organization and also developed concepts for a bus shelter and fundraising campaign that offered gifts of phone wallets, tote bags, or t-shirts at certain donation levels (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. SMAD 201: Student call-to-action campaign for Campus Kitchen. Reprinted with permission.

Even though this civically motivated student did not work directly with the organization during her foundation coursework, she was able to use her experience from the class and develop her technical skills while continuing to combat food insecurity. The opportunity to self-determine content within the safety of a foundation course allows students to try out ideas in a training ground and further develop their projects through the creativity model. Over the course of the next semester, this student took a leadership role within Campus Kitchen and, at the time of this writing, continually takes on projects within her upper-level coursework and in extracurriculars to address food insecurity.

Case Study 2: Capstone Experience

Another example of the implementation of the creativity model is represented in the second author’s community-based research. This included an interdisciplinary project for capstone students in interactive design (SMAD 408) and computer information systems (CIS 484) to apply their skills and better understand the potential role of design in society. As many students typically prepare for opportunities outside of academia, addressing a wicked problem in a culminating project allows students to apply their civic knowledge to issues within a larger community and to participate in collective action that values faculty research and public education.

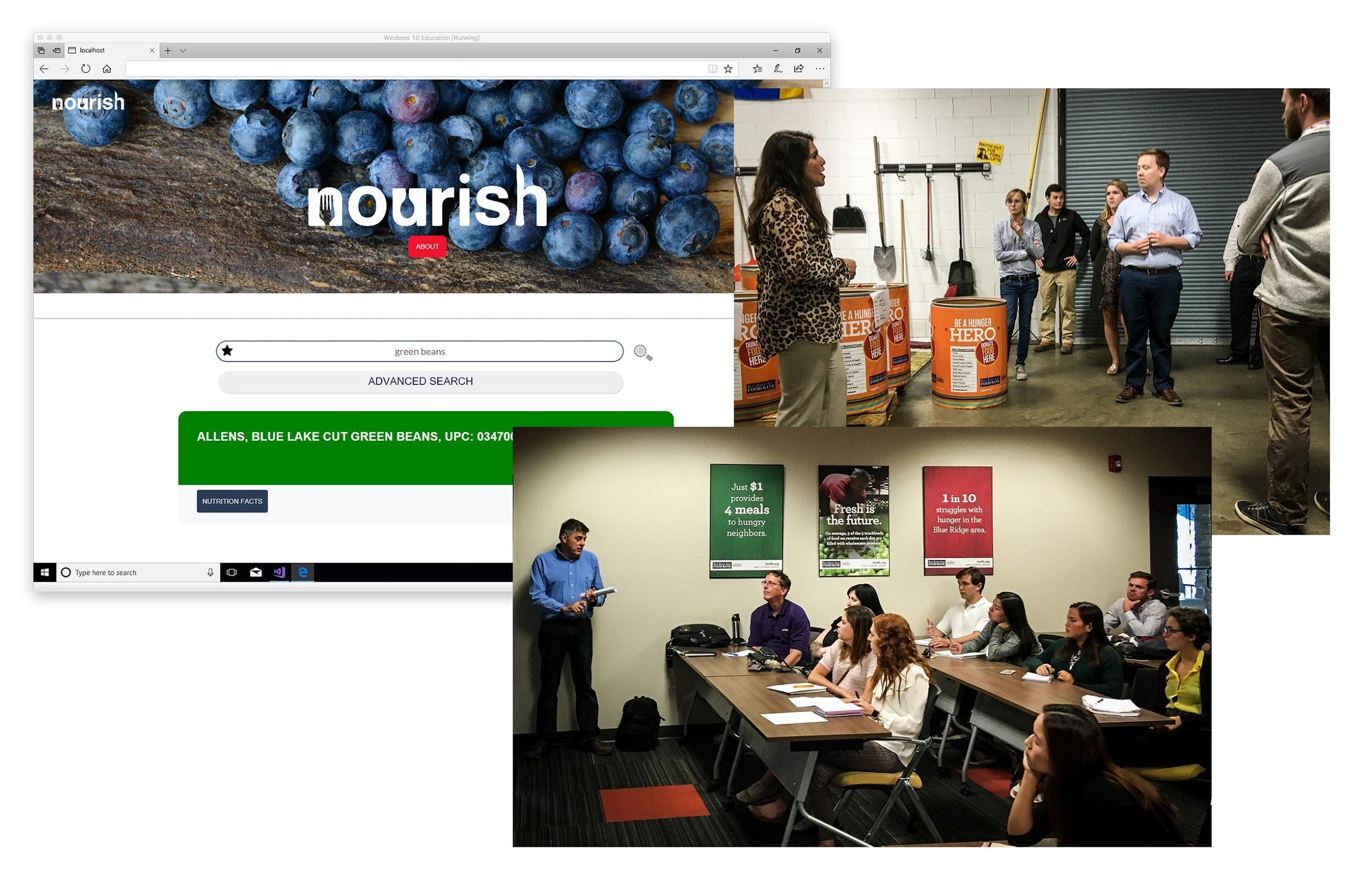

Through a campus–community partnership, teams of students developed an innovative approach to solving the critical problem of food insecurity and achieving a vision of a hunger-free and healthy America. This collaborative effort between the Blue Ridge Area Food Bank and JMU aims to improve the food bank’s ability to provide nourishing food and make informed purchasing decisions. Individual collaborators included faculty, researchers, and community partners with expertise within a variety of professional disciplines, including dietetics, health sciences, media art and design, and computer information systems. Three colleges within JMU combined efforts to offer an integrative learning opportunity for students in two undergraduate degree programs to build a technology around an evidence-based food scoring system. Students created an informational system that allows people to quickly search and identify healthier food options with visual stop-light cues. “Nourish,” the current prototype, is both an analytical and creative approach to solving the wicked problem of food insecurity (see http://nourish.us.org). The system is a web-based interface centered on a user experience that is streamlined, data-driven, and easy-to-use, and aims to educate the public and inform future decisions about food purchases. The student work included the creation of a promotional video to help introduce the product, showcase its primary features, and highlight the benefits to the community (see Figure 3).

[https://drive.google.com/file/d/1u8Z4ws8toekt9D3-YlBw9yUoSpfGevjF/view?usp=sharing]

Figure 3. Promotional video for Nourish. Reprinted with permission.

To encourage outreach and inspire curiosity, students toured the facilities of a local food bank and participated in a kickoff meeting, which allowed the stakeholders to present the project’s objectives and establish a dialogue between community partners and students. Through a series of formal checkpoints, work was competitively selected by the food bank for another iteration based on the quality of each team’s research, insights from expert consultants, and continued dialogues. Each iteration added new perspectives, often including differing opinions, thereby fostering ambiguity within the creativity model. As part of the project’s pedagogy, alumni offered mentorship and outside expertise to encourage risk taking, build trust, and guide discussions toward self-initiated improvements (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. SMAD 408: Collaborative capstone project for Blue Ridge Area Food Bank. Reprinted with permission.

Students enrolled in SMAD 408 culminate their experience with formal presentations to a live public audience, which includes community partners, faculty, peer groups, alumni, industry leaders, and rising capstone students. As a demonstration of their civic knowledge, in addition to serving as a call for collective action, this inspiring work helps each generation of students improve their technical skills and, more importantly, encourage further pursuit of civically minded projects. The Nourish system was presented by the collaborative research team to key stakeholders of Feeding America, the largest hunger-relief organization in the United States, as part of ongoing efforts to increase access to nutritious foods through the use of technology. Faculty, students, and alumni maintain an ongoing relationship as partners in valuable community-based research and regularly consult with the food bank to guide design improvements for the system.

Concluding Thoughts

As faculty explore opportunities to engage with new collaborators to enhance civic knowledge and collective action across all majors, it is important to consider how existing frameworks can connect creative activities responsible for inspiring change. The examples from within the School of Media Arts and Design at James Madison University offer a model for fostering greater imagination and open-mindedness within undergraduate education while increasing the opportunity to engage audiences. The creativity model, when used in a scaffolded approach—both within and across disciplines—can give students the confidence and motivation to use the knowledge and skills they have acquired and at the same time reinforce civic values and, more importantly, civic action. The processes and projects utilizing the creativity model encourage student curiosity, and the continued exercise of creative energy for personal and social responsibility can be leveraged for a lifetime.

References

American Psychological Association. (2004). Increasing student success through instruction in self-determination. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/research/action/success.aspx

Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. (2013). Design and social impact: A cross-sectoral agenda for design education, research and practice. New York: Smithsonian Institution Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Design-and-Social-Impact.pdf

Costantino, T. (2015). Lessons from art and design education: The role of in-process critique in the creative inquiry process. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(2), 118-121. doi:10.1037/aca0000013

Forster, I. (2018). Resisting reductivism & breaking the bubble: Barbara Kruger. Retrieved from https://art21.org/read/barbara-kruger-resisting-reductivism-breaking-the-bubble/

Heller, S. (2017). Five graphic design ideas from the Russian Revolution. Retrieved from https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/five-things-graphic-designers-owe-to-russia

Hoffman, D., Domagal-Goldman, J., King, S., & Robinson, V. (2018). Building a CLDE theory of change: 5 essays and an invitation. Retrieved from https://www.naspa.org/constituent-groups/posts/building-a-clde-theory-of-change-5-essays-and-an-invitation

Kolko, J. (2012). Wicked problems: Problems worth solving—A handbook & a call to action. Austin, TX: Austin Center for Design. Retrieved from https://www.wickedproblems.com/read.php

Little, B. (2016). Inside America’s shocking WWII propaganda machine. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/12/world-war-2-propaganda-history-books/

National Portrait Gallery. (n.d.). UnSeen: Our past in a new light, Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar. Retrieved from http://npg.si.edu/exhibition/unseen-our-past-new-light-ken-gonzales-day-and-titus-kaphar

National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement. (2012). A crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Swol, C. (2018). Creativity-infused pedagogy to foster a civic consciousness. Bringing Theory to Practice Newsletter, Fall(1), 3-5. Retrieved from https://www.bttop.org/newsletters/fall-2018-newsletter

Authors

Adrienne Hooker. With more than ten years teaching in the classroom, Hooker focuses on design basics, the creative process, and visual communication in foundation courses while bringing real-world experience and contemporary theory to her students in upper-level courses. She has co-written and implemented large grants, directed a student-run design center, and presented papers and workshops at national and international educators conferences. Adrienne’s work has been in various juried exhibitions and has won regional and national honors from American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) and University and Colleges Des0igners Association (UCDA). Professor Hooker holds an M.F.A. in graphic design from Indiana University Bloomington with a focus on book arts and letterpress. She also earned two bachelor of fine arts degrees from Drake University in Des Moines Iowa with an emphasis in graphic design and printmaking. Her creative work reflects the places she has been, and demonstrates a sense of home.

Adrienne Hooker. With more than ten years teaching in the classroom, Hooker focuses on design basics, the creative process, and visual communication in foundation courses while bringing real-world experience and contemporary theory to her students in upper-level courses. She has co-written and implemented large grants, directed a student-run design center, and presented papers and workshops at national and international educators conferences. Adrienne’s work has been in various juried exhibitions and has won regional and national honors from American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) and University and Colleges Des0igners Association (UCDA). Professor Hooker holds an M.F.A. in graphic design from Indiana University Bloomington with a focus on book arts and letterpress. She also earned two bachelor of fine arts degrees from Drake University in Des Moines Iowa with an emphasis in graphic design and printmaking. Her creative work reflects the places she has been, and demonstrates a sense of home.

Carol-lynn Swol is a Program Associate working on Civic Learning and Democracy Initiatives at the Association of American Colleges and Universities. Prior to AAC&U her professional experience in higher education was as tenured art faculty at Kishwaukee Community College in Illinois, and after moving to Maryland taught art at Montgomery College. Her course project parameters focused heavily on student driven content where scaffolding within a semester fostered an ongoing trajectory designed to exhibit civic values and actions through the creative process. She received her B.A. in Anthropology from the University of Connecticut and her M.F.A in Metalsmithing and Jewelry Design from Indiana University Bloomington.

Carol-lynn Swol is a Program Associate working on Civic Learning and Democracy Initiatives at the Association of American Colleges and Universities. Prior to AAC&U her professional experience in higher education was as tenured art faculty at Kishwaukee Community College in Illinois, and after moving to Maryland taught art at Montgomery College. Her course project parameters focused heavily on student driven content where scaffolding within a semester fostered an ongoing trajectory designed to exhibit civic values and actions through the creative process. She received her B.A. in Anthropology from the University of Connecticut and her M.F.A in Metalsmithing and Jewelry Design from Indiana University Bloomington.

David Wang. With more than twenty years of industry experience, David Wang’s work as an art director, photographer, and interactive developer translates to sensible design decisions. He teaches foundation courses in SMAD with an emphasis on creative process and interactive design. His experience in the classroom helps students engage in valuable research that focuses on design in society. He studied fine art and design with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Graphic Design from Drake University and a Master of Fine Arts in Communication Design from Louisiana Tech University. His research interests include grant sponsored work for developing technology to help eliminate food insecurity.

David Wang. With more than twenty years of industry experience, David Wang’s work as an art director, photographer, and interactive developer translates to sensible design decisions. He teaches foundation courses in SMAD with an emphasis on creative process and interactive design. His experience in the classroom helps students engage in valuable research that focuses on design in society. He studied fine art and design with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Graphic Design from Drake University and a Master of Fine Arts in Communication Design from Louisiana Tech University. His research interests include grant sponsored work for developing technology to help eliminate food insecurity.