Author Note

Amy C. Blansit, Department of Kinesiology, Missouri State University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Amy C. Blansit, Senior Instructor, Department of Kinesiology, Missouri State University, McDonald Arena 206, 901 S. National Avenue, Springfield, MO 65897. Phone: (417) 836-5209. Email: AmyBlansit@MissouriState.edu

Abstract

The research discussed in this article sought to study the Reaching Independence through Support and Education (RISE) pilot program and stability factors of low socioeconomic groups. Self-sufficiency programs like RISE focus on households moving from crisis to empowerment, no longer relying on subsidies; however, gaining employment and securing housing alone do not create socioeconomic stability. It was therefore determined that the RISE program should be evaluated to determine its effectiveness at ending dependency. Thirty-four individuals, representing 30.6% of RISE participants, were included in this evaluation study, which used logistic regression techniques to explore 16 items on the RISE Self-Sufficiency Assessment (RSSA). The study results showed that RISE participants derived significant economic benefits from the program and indicated that food security was the greatest mediator of increases in the federal poverty guideline (FPG). The slope of the overall RSSA revealed that for every one increase in the total RSSA score, there were 24.01 increases in %FPG. Participants who had increased food security saw significant increases in %FPG of 25.25. These findings suggest that participants’ perceptions of improved food security is the best mediator of increased federal poverty guidelines.

In April 2016, the Community Foundation of the Ozarks commissioned a 5-year pilot program, the Northwest Project, to address poverty in Springfield, Missouri. The project initiated an asset-building program called Reaching Independence through Support and Education (RISE), which was designed to encourage self-sufficiency through the development of human and social capital. Eligible participants in the RISE program had at least one dependent and fell below the 200% federal poverty guideline (%FPG, described in the following section). In addition, participants had to have already achieved the following: stable housing, access to transportation, and employability with a high school education or equivalent. The RISE Self-Sufficiency Assessment (RSSA) was used by RISE staff at baseline and every 6 months to determine if participants were experiencing improvements in self-sufficiency while in the RISE program. The RSSA was also developed to determine which RSSA items could predict upward mobility in socioeconomic status. Results revealed significant improvements in overall self-sufficiency and for items relating to employment, education, income, quality childcare, legal resolution (criminal), and food security. Furthermore, the RSSA was used to determine if these improvements impacted participants’ %FPG. Though the terms poverty, food security, and self-sufficiency are often used, they are less frequently defined by those who employ them. Typically, these terms are conceptualized as a continuum; however, for this research and the work with the RISE program, quantifiable measures were defined.

Percent Federal Poverty Guideline

The percent federal poverty guideline was created by the Social Security Administration in 1963 to determine an individual’s or household’s eligibility for federal assistance programs. The qualifications for assistance were developed based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s assessed average dollar value of food. Further assessment of family dynamics found that for a family of three or more, the total cost of food was about one third of their net income. Today, the %FPG is frequently used to determine access to most federal programs. Since the standard for determining the federal poverty threshold does not consider inflated costs of housing, utilities, or medical care, most federal programs have inclusion criteria of household income below the 185% FPG but some as high as 200% FPG (Dinan, 2009). To better understand income levels based on 2020 income, a family of three would have the following income and %FPG: $21,720/100%; $29,322/185%; $43,440/200% (ASPE, 2020).

Self-Sufficiency

The Family Self-Sufficiency (FSS) program grew out of the National Affordable Housing Act of 1990, which intended to improve self-sufficiency through education, skill development, case management, and referrals to resources (Silva et al., 2011). Although a national standard does not exist, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requires public housing authorities to administer family self-sufficiency assessments to predict household self-sufficiency. HUD suggests that all FSS tools should include questions that address the following: family demographics, education, employment, finances and assets, and barriers or needs. Some FSS tools include a 5-point Likert scale, while others use a 10-point scale. Though most include 15–18 questions, others include 100 questions (HUD, 2017). Organizations that use FSS tools typically help households increase wages by building social and human capital. Human capital is improved through education and skill development, with a focus on higher paying jobs. Social capital is developed by expanding networks and access to resources. Therefore, poverty prevention programs must address issues beyond budgeting since many low-income jobs are volatile and developing stability below 200% FPG has proven difficult. As a result, for over 30 years, state and federal assistance programs have been using between 125% and 200% of a poverty guideline as an eligibility requirement (Dinan, 2009; Fisher 1992).

RISE Program

Once participants are accepted into the program, personal development managers interview participants to collect data and assist in setting short- and long-term goals. Participants agree to a minimum of 24 months of personalized coaching, weekly small-group classes, and job training, skill development, or education tailored to their abilities and goals. These agreements require participants to reach objectives toward attaining their goals by specific dates, with the overall objective of becoming financially self-sufficient within 2 to 5 years of program entry. Personal development managers provide referrals to counseling and resources. Weekly classes cover a variety of topics that include developing self-efficacy, asset development and credit counseling, and homebuyer education. Referral resources include childcare, job openings, legal resolution, and food resources, to name a few. Completion of 1 year of the RISE program includes three college credits of coursework toward achieving an education goal. RISE participants also earn incentive dollars and receive free bus passes as well as free tutoring. The RISE program and the support provided by the personal development managers, class facilitators, and community resources are similar to those found in most comprehensive self-sufficiency programs. The primary difference in the RISE program is the weekly classes around specific topics that help improve self-efficacy while helping participants create and reach goals with weekly accountability and support of the facilitators and their peers.

Food Insecurity

The USDA monitors food security annually. Most households (85%–88.5%) report being food secure—that is, having dependable access and funds to provide enough food for a healthy lifestyle. However, within the last 7 years, between 10.5% and 14.9% of households have reported periods of food insecurity as a result of lack of access or finances during the year (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2020; Feeding America, 2015). Several socioeconomic factors are correlated with food insecurity, including unemployment and underemployment, poverty rates, and educational attainment (Furness et al., 2004; Loopstra & Tarasuk, 2013). Other circumstances leading to food insecurity include stagnant wages in combination with increased housing and food costs (Gundersen, 2013; Holben & American Dietetic Association, 2010.) As poverty rates and stagnant wages in the United States remain unchanged, food insecurity continues to be a national concern. From 2011 through 2013, approximately 49 million households (14.9%) reported they were not able to meet basic food needs at some point within the year. During this same period, rates of food insecurity were significantly higher in the state of Missouri (Barker, 2015; Coleman-Jensen et al., 2020; Feeding America, 2015). Prior to COVID-19, food security had decreased slightly between 2013 and 2019. According to the USDA, 10.5% of the general U.S. population reported food insecurity at some point in 2019, representing a modest decrease from 11.1% of the population reporting food insecurity in 2018. However, Coleman-Jensen et al. (2019) found that nearly 30% of low-income households (i.e., those at or below 185% FPG) reported food insecurity. Although poverty is related to food insecurity, it is important to note that individuals at or below federal poverty guidelines can be food secure (Gundersen, 2013). To understand this, food security must be clearly defined.

Food security is influenced by more than access to food. The United States does not have famine; thus, the limiting factor of access is more than scarcity. Access can be limited by physical factors, like food deserts, or financial factors, such as increasing food costs and stagnant wages. Food security is also subjective. One household may not have the quality of food it desires for nutritional health and consider itself insecure, while another household may actually have no quantity of food and experiences physical hunger. True food security comprises the ability to physically possess nutrients and have the economic means to access food with nutritional value which promotes health (McDonald, 2010; Webb et al., 2006). According to the Rome Declaration on World Food Security (1996), the following definition, developed at the World Food Summit of 1996, encompasses these constructs: “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritional food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (p. 1405S). This definition is most widely accepted because it considers availability, access, and utilization (Webb et al., 2006).

Food insecurity is often linked to unemployment and increased food costs. During the 2007 Great Recession, food costs increased, as did unemployment—and food cost increases have continued since the recession ended. By 2012, many households had recovered; however, food insecurity rates remained elevated, leading researchers to suggest that food inflation was the cause of unchanged rates of food insecurity. This conclusion was supported by research conducted with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients, who reported that the greatest cause of food insecurity was high food prices (Nord et al., 2014). According to Coleman-Jensen et al. (2020), households with a median income spend an average of 24% more for food than same-size households that rate themselves as food insecure and that include government assistance in their total food cost.

Methods

The aim of this study was to determine if the RISE program was effective at moving individuals out of poverty according to changes in household income and self-reported self-sufficiency measures. The Northwest Project began on April 1, 2016, and continues presently to provide services to participants. The results of this study represent data collected between April 1, 2016, and December 31, 2019. The program provides the following services to participants: weekly group education classes; one-on-one personal development meetings; and community connections that provide financial literacy and banking resources, education and job skills training, and legal resolution.

Participants

Twenty-nine females and five males (n = 34) participated in this study. Initial mean annual household income was $22,358, with an average %FPG of 82.92%. In the follow-up measurement, the mean annual household income was $30,357, with an average %FPG of 116.65%.

Data Collection

The Northwest Project is an ongoing study that was originally a grant-funded program, as described in the introduction. The program collects information related to demographics and socioeconomic characteristics of participants and their families. Data for this study were collected by project staff every 6 months from 2016 to 2019. Data were gathered using verbal questionnaires and entered into a HIPAA-protected online database; paper copies were also used to compare for accuracy. Intake focused on a broad array of outcomes, including employment status, financial health, physical health, emotional wellbeing, skill development, academic achievement, social relationships, and community engagement.

Measures

The Northwest Project staff created the RISE Self-Sufficiency Assessment measurement tool to assist in case management, self-assessment, and goal setting by participants, and to gauge a household’s potential to become self-reliant after enrollment in the RISE program. To develop the methodology for this measurement tool, HUD recommendations for self-sufficiency matrices were compared against national standards for measurements of self-sufficiency. For example, in the RSSA, a rating of 5 for a household was only achieved if the family was currently living in permanent adequate housing and the cost did not exceed 30% of family income in unsubsidized housing. Many self-sufficiency assessments do not consider the percentage of household expenses in relation to total household net income. The definition of affordable housing varies among communities; however, worldwide, conventional public policy indicates that housing expenses (i.e., rent/mortgage and utilities) should be no more than 30% of household income. This indicator of stable housing evolved out of the U.S. National Housing Act of 1937. The measure began at 20% of household income but increased over the decades as households had difficulty achieving the American dream of homeownership. Thus, as housing costs increased, the disproportionate spending on homeownership led to the increase to 30% (Linneman & Megbolugbe, 1992).

The development of the RSSA tool was informed by the idea that self-reliance involves more than an increase in socioeconomic status and that a family’s socio-ecological environment should be considered in its potential for achieving overall wellbeing. The RSSA includes quantitative measures like educational attainment, income, and transportation. Specifically, it consists of the following 16 items: Housing; Transportation; Employment; Education/Academic Attainment; Income/Budget; Health Insurance; Physical Health; Mental Health/Substance Abuse; Psychosocial and Environmental Stressors; Parenting Skills; Quality Childcare; Legal: Criminal and Non-Criminal; Support Systems; Food; Home Safety; and Community Involvement.

Each participant is interviewed, and a rating is assigned to each item in one of five categories: Crisis, Vulnerable, Safe, Building Capacity, or Empowered/Thriving. The RSSA was administered every 6 months and is designed to be objective, reliable, and valid while measuring small, incremental change as participants progress with their objectives and goals. Each item is not weighted—no item is more important than any other in reaching self-sufficiency. The scale itself is subjective, and each participant determines what self-sufficiency means for them. Organizations like RISE that use any version of a self-sufficiency assessment typically assist households in increasing wages by building social and human capital. Human capital improves through education and skill development, with a focus on higher paying jobs. Social capital develops through the expansion of networks and increased access to resources. Programming goes beyond simply budgeting as many low-income jobs are volatile and developing stability below 200% FPG has proven difficult. Therefore %FPG is just one consideration for self-sufficiency. The following is a sample question from the RSSA (with item ratings in parentheses):

FOOD SECURITY: Please select which of the following describes your family’s food situation:

- No food or means to prepare it. Rely primarily on sources of free or low-cost food. (1)

- Household meeting most food needs with SNAP benefits. (2)

- Can meet basic food needs, but require occasional assistance. (3)

- Can meet basic food needs without assistance. (4)

- Can choose to purchase any food household desires. (5)

Statistical Analysis

Before the data were analyzed, they were screened for accuracy, missing data, outliers, and violation of assumptions. The data appeared to be accurate and consisted of 111 participants who had completed the RISE program. Of those participants, 48 (43%) were considered active participants, and seven were recent graduates who had not reached the 6-month second data collection point. Only 41 participants (36.9%) had at least two measures and were active members in the RISE program. An additional seven participants did not have complete points for post-data; thus, they were excluded from the statistical analyses. Additionally, missing data appeared random for other participants and were excluded pairwise. Difference scores from the pretest and posttest data were derived for each of the variables. Outliers and assumptions were evaluated based on the difference scores. One outlier was identified by obtaining z-scores above the absolute value of 3 and was removed. The violation of assumptions was also examined prior to performing analyses. Linearity, homogeneity, and homoscedasticity were all met. Normality was also met but showed a slight negative skew for average self-sufficiency and a slight positive skew for percent federal poverty guideline.

Two reliability analyses were computed to determine the reliability of the RISE Self-Sufficiency Assessment for the pretest data and posttest data. The reliability of the scale was assessed along with all the items as a whole. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0 to 1.0. Alphas for scales used in practice require an alpha above 0.7, and an ideal Cronbach’s alpha in a reliability analysis is .8 or higher. The pretest was considered reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .76. Similar results were shown for the posttest (α = .80). Additionally, the individual items were assessed by evaluating the stability and the Cronbach’s alpha when items were removed. If an item was removed, the Cronbach’s alphas remained consistent around .72 to .78 for the pretest assessment and between .76 and .81 for the posttest assessment. The lack of change in the Cronbach’s alpha when an item was removed suggests that the items were reliable and that each item did not hold significant “weight.” The means and standard deviations also remained moderately consistent, suggesting that the assessment was moderately stable.

Results

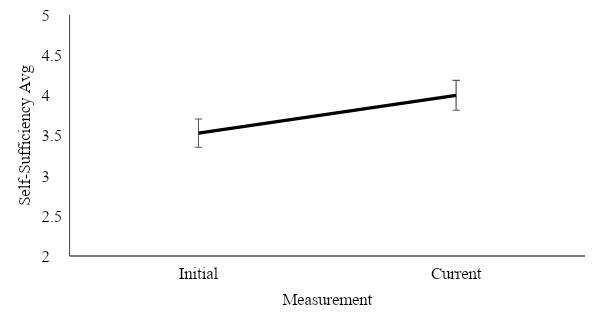

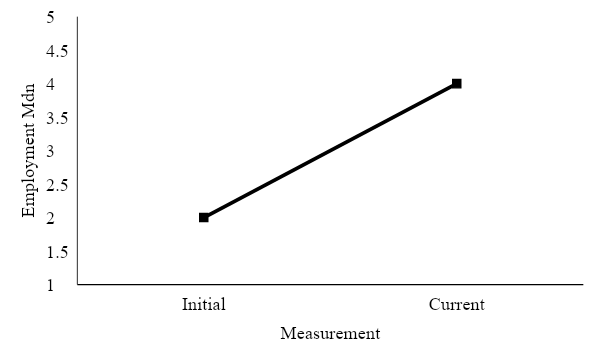

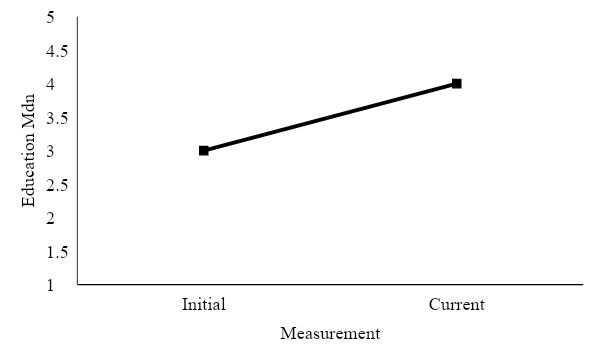

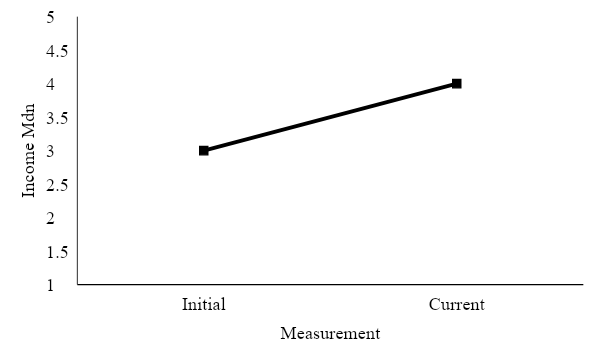

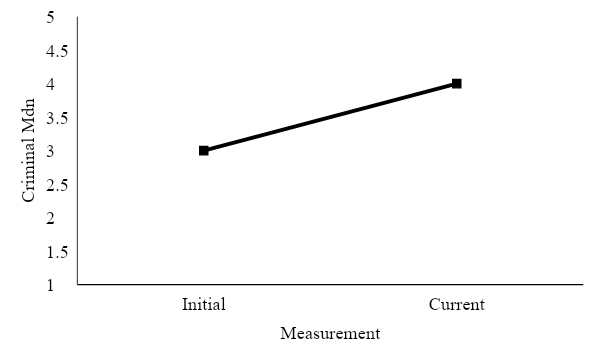

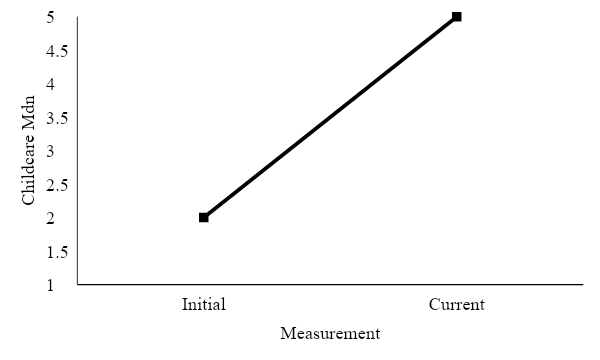

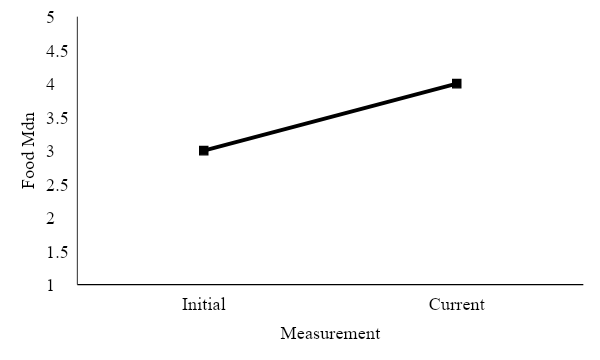

A series of paired-samples t-tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests when appropriate) were performed to assess the change in self-sufficiency for participants in the RISE program. Analyses consisted of evaluating self-sufficiency by using the self-sufficiency average and the individual items on the self-sufficiency assessment. Results revealed significant improvements in self-sufficiency overall and for the areas relating to employment, education, income, childcare, legal resolution (criminal), and food security. Participants became more self-sufficient overall, t(32) = 5.86, p < .001, d = 1.03. The childcare and employment self-sufficiency measures appeared to show the largest improvement from initial to current status. Moreover, when the p-value was adjusted to control for a type I error (p < .003), education and criminal self-sufficiency measures no longer showed a significant improvement. Table 1 shows the results of the analyses for the individual self-sufficiency measures. Figures 1–7 depict the results for the significant t-tests.

Table 1

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Analysis Results for the Self-Sufficiency Measures

|

Self-Sufficiency Measures |

W |

p |

Rank Biserial Correlation (rrb) |

|

Housing |

53.5 |

.724 |

-.11 |

|

Transportation |

104 |

.182 |

.36 |

|

Employment |

235 |

<.001** |

.86 |

|

Education |

135 |

.005* |

.77 |

|

Income |

218.5 |

.002** |

.73 |

|

Insurance |

154.5 |

.622 |

.12 |

|

Physical |

106 |

.984 |

.01 |

|

Mental |

69 |

.466 |

-.19 |

|

Psychosocial |

224.5 |

.091 |

.38 |

|

Parenting |

138 |

.065 |

.45 |

|

Childcare |

159 |

.001** |

.86 |

|

Criminal |

28 |

.015* |

.98 |

|

Non-Criminal |

58 |

.392 |

.28 |

|

Support System |

95 |

.385 |

.24 |

|

Food |

140.5 |

.015* |

.64 |

|

Home Safety |

13 |

.17 |

.73 |

|

Community |

26 |

.173 |

.16 |

Note. *p < .05. **p < .003.

Figure 1

Mean Regression Slope of Total Self-Sufficiency Measure

Figure 2

Mean Regression Slope of Employment

Figure 3

Mean Regression Slope of Education

Figure 4

Mean Regression Slope of Income

Figure 5

Mean Regression Slope of Legal Resolution (Criminal)

Figure 6

Mean Regression Slope of Childcare

Figure 7

Mean Regression Slope of Food Security

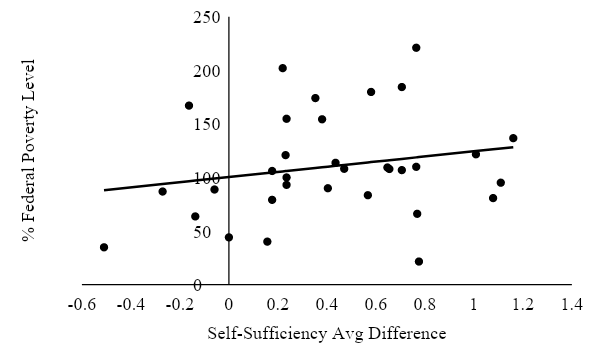

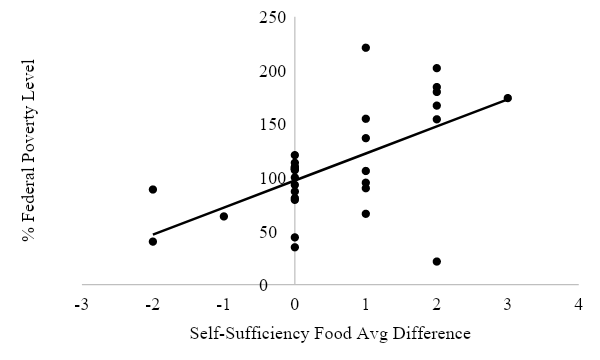

A series of simple linear regressions (SLRs) were performed to assess if the change in self-sufficiency predicted a participant’s current percent federal poverty guideline. In other words, the SLRs were performed to help determine the measures that had an impact on participants’ %FPG. Difference scores of the pre and post self-sufficiency assessment items were derived to measure the change for each of the variables. Also, difference scores were calculated for the self-sufficiency average scores. Results revealed that self-sufficiency overall (average difference scores) did not have an impact on %FPG. However, the slope was rather large; for every one increase in self-sufficiency, there were 24.01 increases in %FPG (see Figure 8 for a depiction of the relationship). When the individual self-sufficiency items were assessed, food security appeared to have a significant impact on participants’ %FPG. Specifically, there was a significant positive relationship between the self-sufficiency food security item and %FPG; that is, as participants were more self-sufficient in relation to food, the %FPG percentage increased (Figure 9). In fact, for every one increase in food-security self-sufficiency, there were 25.25 increases in the %FPG. Therefore, as participants were more food self-sufficient, the higher their income per household member. While education and psychosocial factors were not significant predictors of %FPG, the slopes were rather large. Specifically, for every one increase in education self-sufficiency, there were 12.13 increases in %FPG, and for every one increase in psychosocial self-sufficiency, there were 8.24 increases in %FPG. Table 2 shows the results of the SLRs.

Figure 8

Relationship of Total RSSA Score and Federal Poverty Guideline

Figure 9

Relationship of Food Security and Federal Poverty Guideline

Table 2

Simple Linear Regression Results for the Self-Sufficiency Measures

|

Self-Sufficiency Predictors |

r |

b |

β |

t |

p |

r2 |

|

Self-Sufficiency Average |

.2 |

24.01 |

0..2 |

1.16 |

.256 |

.04 |

|

Housing |

-.02 |

-0.74 |

-0.02 |

-0.1 |

.922 |

.0004 |

|

Transportation |

-.16 |

-6.42 |

-0.16 |

-0.88 |

.384 |

.03 |

|

Employment |

.21 |

6.53 |

.21 |

1.17 |

.251 |

.04 |

|

Education |

.3 |

12.13 |

.3 |

1.75 |

.09 |

.09 |

|

Income |

.07 |

3.29 |

.07 |

0.39 |

.7 |

.005 |

|

Insurance |

.07 |

2.06 |

.07 |

0.41 |

.683 |

.005 |

|

Physical |

-.11 |

-4.43 |

-0.11 |

-0.59 |

.557 |

.01 |

|

Mental |

.1 |

3.93 |

0.10 |

0.55 |

.583 |

.01 |

|

Psychosocial |

.26 |

8.24 |

0.26 |

1.49 |

.145 |

.07 |

|

Parenting |

.04 |

1.94 |

0.04 |

0.19 |

.850 |

.002 |

|

Childcare |

-.003 |

-0.08 |

-0.003 |

-0.02 |

.987 |

.000 |

|

Criminal |

.12 |

7.32 |

0.12 |

0.65 |

.518 |

.01 |

|

Non-Criminal |

.01 |

0.53 |

0.01 |

0.07 |

.943 |

.0001 |

|

Support System |

-.17 |

-5.86 |

-0.17 |

-0.98 |

.335 |

.03 |

|

Food |

.56 |

25.25 |

0.56 |

3.88 |

<.001** |

.31 |

|

Home Safety |

-.16 |

-7.39 |

-0.16 |

-0.53 |

.604 |

.03 |

|

Community |

-.08 |

-2.93 |

-0.08 |

-0.28 |

.788 |

.01 |

Note. *p < .05. **p < .003.

Additionally, a series of SLRs were performed to assess if the change in self-sufficiency predicted change in federal poverty guideline (∆FPG). Difference scores of the %FPG were derived to measure the change in the %FPG. Results revealed that self-sufficiency overall (average difference scores) did not have an impact on ∆FPG; however, when the individual self-sufficiency items were assessed, food security appeared to have a significant impact on participants’ ∆FPG. Specifically, there was a significant positive relationship between ∆Food Security and ∆%FPG; as participants were more self-sufficient for food, the FPG percentage appeared to increase. In fact, for every one increase in food-security self-sufficiency, there were 16.27 increases in ∆%FPG.

Discussion

This study revealed that the participants in the RISE program became more self-sufficient. Income alone is not enough to predict self-sufficiency; however, an increase in multiple RSSA factors leads to self-sufficiency. RISE participants experienced an annual household %FPG income increase of 35.78%, revealing that the RISE program did result in significant improvements in financial measurements. Self-sufficiency also increased significantly in areas relating to employment, education, childcare, legal resolution (criminal), and food security. Average participants joined the program with incomes that “[met] basic needs, but attained insufficient funds for emergencies”; however, their current income “[met] basic needs and allow[ed] for minor emergencies.” A majority of Americans fall into this category. According to the Federal Reserve (2020), in 2019, 65% of Americans did not have an extra $400 to cover unexpected expenses, such as a medical bill. The lack of savings for emergent needs (e.g., car repairs) means that many employees are often unable to get to work. Lack of transportation is a common cause of social exclusion, increased chronic health conditions, and employee absenteeism, creating a cyclical financial crisis (Agarwal et al., 2019). At the initial intake, the average participant reported that they were “unemployed for less than 3 months” but were currently “full-time employees with no benefits.” Although the participants reported improved employment due to RISE participation, it is essential to note they did not receive benefits, putting them at extremely high risk for incurring unaffordable medical expenses. This risk, which can lead to financial catastrophe for many working Americans, has been well documented for more than a decade. Research has repeatedly shown that being uninsured is linked to increased morbidity and mortality rates, decreased quality of life, decreased work productivity, and overall lack of self-sufficiency (Finkelstein & McKnight, 2005; McWilliams, 2009; McWilliams et al., 2007). As a result of RISE participation, members saw improvements in income and employment; however, they remained at high risk for financial catastrophes since they could not secure the safety net necessary to recover from medical or other unbudgeted expenses. Additionally, at intake, participants reported that “childcare and subsidies were available, but the childcare provider did not accept subsidy or was unaffordable”; however, participants currently reported “childcare to be available, affordable, good quality and there is at least one emergency backup caregiver.” Individuals with children have a significant barrier to employment if affordable and quality childcare is not available. An improvement in access to childcare increases an individual’s capacity to be employed and to maintain employment—and access to childcare influences more than just the adult. Access to quality childcare influences the child’s potential for upward mobility, having a multi-generational influence on self-sufficiency. Early childhood education has been shown to create upward mobility, decreasing the demand for programs like RISE later in life. Quality childcare reduces the achievement gap and improves cognitive function, and also enhances the social skills necessary throughout life (McCoy et al., 2017).

Education improved between intake and current measurements. The average participant reported initially that they “lack[ed] academic skills that limit employment or other goal attainment,” but currently they reported obtaining some academic skills and now felt that these skills “only occasionally limit[ed] employment or other goal attainment.” For participants who reported that they had unresolved legal concerns, the average response included that they were on “probation and had no new charges filed.” Participants received assistance through the RISE program and currently stated “no criminal history.”

Finally, at intake, the average participant reported that they “[met] basic food needs, but require[d] occasional assistance,” whereas currently they reported that they “[met] basic food needs without assistance.” These financial stability factors do have potential to increase an individual’s capacity for stability. Previous studies have suggested that the development of human and social capital may help protect against food insecurity (Chhabra et al., 2014; Dean et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2004). Previous studies have shown significant changes in food security related to improvements in social determinants of health. Food security is understood to be a significant determinant of overall health and the potential for improved development. It has been well documented that food insecurity is one of the most influential factors on the overall health of individuals. Food insecurity affects 11%–14% of U.S. households and causes disproportionate chronic diseases among those individuals, representing a national health crisis (Coleman-Jensen et al, 2020; Feeding America, 2020). Artiga and Hinton (2018) found that “healthcare costs for food-insecure adults were $1,834 higher than for food-secure adults—totaling $52.6 billion across all food-insecure households. These additional costs include all direct healthcare-generated costs, like clinic visits, hospitalizations and prescription medications” (p. 3). Desmond (2016) reported that public housing with rents set at 30% of household income increased the disposable income of individuals, who in turn spent more money on food. Long term, these individuals saw improvements in their children’s health (Desmond, 2016).

Specifically, there was a significant positive relationship between the food-security self-sufficiency item and %FPG; as participants reported feeling more self-sufficient in relation to food, the %FPG increased (see Figure 9). In fact, for every one increase in food-security self-sufficiency score, there were 25.25 increases in the %FPG. Therefore, as participants felt more food secure, the higher their income per household member. Finally, while education and psychosocial factors were not significant predictors of %FPG, the slopes were rather large. This information can be used to predict changes in self-sufficiency. For every one increase in education self-sufficiency, there were 12.13 increases in %FPG, and for every one increase in psychosocial self-sufficiency, there were 8.24 increases in %FPG. RISE programming can assist participants in setting and achieving goals focused on items that have high slopes in order to improve self-sufficiency. One of the limitations of the study was its small sample size. As the program continues, these assessments will be revisited. Additionally, the number of months between the pretest and posttest were not consistent. Participants joined the program at different intervals. Some participants were in the program for 1 year, while others were in the program for 2 years. Also, the RSSA measurement is conducted in a single point of time, but household dynamics can change quickly. For instance, if a participant was laid off for a short period and the assessment was conducted at that time, the participant was considered unemployed.

Recommendations for future studies include repeating measures as additional graduates meet the 6-month post-measurement point. Future research is planned that will expand the comparison of each 6-month data measurement to determine when in the program RISE participants see the greatest changes in self-sufficiency and annual household income.

Conclusion

Recent research on family self-sufficiency programs, like RISE, has provided a more complete understanding of the components necessary to assist individuals in increasing household income and self-sufficiency. The purpose of this research was to assess if participants showed improvements in self-sufficiency while participating in the RISE program and to identify which measurements were effective in predicting increases in household income and self-sufficiency. Current findings suggest that food security plays a critical role in an individual’s perception of household stability. Study results also revealed significant improvements in self-sufficiency overall measurement and for the areas relating to employment, education, income, childcare, and legal resolution (criminal). Furthermore, these improvements in self-sufficiency impacted participants’ %FPG. According to the results, the food-security item on the self-sufficiency assessment appeared to have a significant impact on participants’ %FPG. Specifically, there was a significant positive relationship between these two measurements; as participants were more self-sufficient in relation to food, the %FPG increased. Lastly, self-sufficiency overall (average difference scores) did not significantly impact %FPG. However, the slope was rather large; thus, for every one increase in self-sufficiency, there were 24.01 increases in %FPG. Overall, the implications of the findings suggest that self-sufficiency programs should include services that lead to improvements in a participant’s employment capacity and education, which influence household income, while also ensuring that childcare, legal resolution, and food security are met.

References

Agarwal, G., Lee, J., McLeod, B., Mahmuda, S., Howard, M., Cockrell, K., & Angeles, R. (2019). Social factors in frequent callers: A description of isolation, poverty and quality of life in those calling emergency medical services frequently. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6964-1

Artiga, S. & Hinton, E. (2018). Beyond health care: The role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Kaiser Family Foundation.

ASPE, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2020). Poverty guidelines. https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

Barker, R. (ed)., Calendar, C. (2015). Health equity series: Food insecurity. Missouri Foundation for Health.

Chhabra, S., Falciglia, G. A., & Lee, S. Y. (2014). Social capital, social support, and food insecurity in food pantry users. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 53(6), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2014.933737

Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M.P., Gregory, C.P., & Singh, A. (2020). Household food security in the United States in 2019. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2504067

Dean, W. R., Sharkey, J. R., & Johnson, C. M. (2011). Food insecurity is associated with social capital, perceived personal disparity, and partnership status among older and senior adults in a largely rural area of central Texas. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2011.567955

Desmond, M. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American city. Crown Publishers/Random House.

Dinan, K. (2009). Budgeting for basic needs—a struggle for working families. National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University.

The Federal Reserve. (2020). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2020-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2019-dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm

Feeding America. (2015). Facts about poverty and hunger in America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/facts

Finkelstein, A., & McKnight, R. (2005). What did Medicare do (and was it worth it)? (No. w11609). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Fisher, G. M. (1992). The development and history of the poverty thresholds. Social Security Bulletin, 55(4), 3–14 .

Furness, B. W., Simon, P. A., Wold, C. M., & Asarian-Anderson, J. (2004). Prevalence and predictors of food insecurity among low-income households in Los Angeles County. Public Health Nutrition, 7(6), 791–794. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004608

Gundersen, C. (2013). Food insecurity is an ongoing national concern. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal, 4, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.112.003244

Holben, D. H., & American Dietetic Association. (2010). Position of the American Dietetic Association: Food insecurity in the United States. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 110(9), 1368–1377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.015

Linneman, P. D., & Megbolugbe, I. F. (1992). Housing affordability: Myth or reality? Urban Studies, 29(3–4), 369–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989220080491

Loopstra, R., & Tarasuk, V. (2013). Severity of household food insecurity is sensitive to change in household income and employment status among low-income families. Journal of Nutrition, 143(8), 1316–1323. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.175414

Martin, K. S., Rogers, B. L., Cook, J. T., & Joseph, H. M. (2004). Social capital is associated with decreased risk of hunger. Social Science & Medicine, 58(12), 2645–2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.026

McCoy, D. C., Yoshikawa, H., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Magnuson, K., Yang, R., Koepp, A., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2017). Impacts of early childhood education on medium- and long-term educational outcomes. Educational Researcher, 46(8), 474–487. http://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17737739

McDonald, B. L. (2010). Food security. Polity.

McWilliams J. M. (2009). Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: Recent evidence and implications. Milbank Quarterly, 87(2), 443–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00564.x

McWilliams, J. M., Meara, E., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2007). Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa067712

Nord, M., Coleman-Jensen, A., & Gregory, C. (2014). Prevalence of U.S. food insecurity is related to changes in unemployment, inflation, and the price of food (No. 1477-2017-3979). https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/262213

The Rome Declaration on World Food Security. (1996). Population and Development Review, 22(4), 807–809. http://doi.org/10.2307/2137827

Silva, L. D., Wijewardena, I., Wood, M., & Kaul, B. (2011). Evaluation of the Family Self-Sufficiency program: Prospective study. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2017). Family Self-Sufficiency: Participant assessments. https://www.hudexchange.info/trainings/fss-program-online-training/2.4-participant-assessments.html

Webb, P., Coates, J., Frongillo, E. A., Rogers, B. L., Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2006). Measuring household food insecurity: Why it’s so important and yet so difficult to do. Journal of Nutrition, 136(5), 1404S–1408S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.5.1404S

Author

Dr. Amy Blansit is a senior instructor in the Kinesiology department at Missouri State University. Dr. Blansit focuses her research on methods for overcoming socioeconomic barriers to self-sufficiency in populations of low socioeconomic status. In collaboration with her work at MSU, Dr. Blansit is the program director for RISE, a poverty alleviation initiative in southwest Missouri. RISE provides opportunities for students to engage in service learning. The success of RISE is the result of a five-year pilot program in partnership with Missouri State, Drury University, and the Drew Lewis Foundation. She is chairman of the Drew Lewis Foundation and operates The Fairbanks, a renovated grade school that now serves as a center for community betterment in Springfield’s Grant Beach neighborhood. Based at The Fairbanks, RISE uses a community-driven development model that couples education and support with neighborhood development and sustainability to help individuals overcome the challenges that have kept them living in poverty. As a result of her work and the collaboration of private and public resources, the community hub has been recognized by the Department of Housing and Urban Development as an EnVision Center. Dr. Blansit was honored as the Person of the Year by Springfield’s magazine Biz 417 in 2017 and has remained on their Biz 100 list each year. She was also awarded the Missouri State Foundation Award for Service and has been recognized by Springfield Business Journal as 40 Under 40, 12 People You Need to Know, and 40 Most Influential Women.

Dr. Amy Blansit is a senior instructor in the Kinesiology department at Missouri State University. Dr. Blansit focuses her research on methods for overcoming socioeconomic barriers to self-sufficiency in populations of low socioeconomic status. In collaboration with her work at MSU, Dr. Blansit is the program director for RISE, a poverty alleviation initiative in southwest Missouri. RISE provides opportunities for students to engage in service learning. The success of RISE is the result of a five-year pilot program in partnership with Missouri State, Drury University, and the Drew Lewis Foundation. She is chairman of the Drew Lewis Foundation and operates The Fairbanks, a renovated grade school that now serves as a center for community betterment in Springfield’s Grant Beach neighborhood. Based at The Fairbanks, RISE uses a community-driven development model that couples education and support with neighborhood development and sustainability to help individuals overcome the challenges that have kept them living in poverty. As a result of her work and the collaboration of private and public resources, the community hub has been recognized by the Department of Housing and Urban Development as an EnVision Center. Dr. Blansit was honored as the Person of the Year by Springfield’s magazine Biz 417 in 2017 and has remained on their Biz 100 list each year. She was also awarded the Missouri State Foundation Award for Service and has been recognized by Springfield Business Journal as 40 Under 40, 12 People You Need to Know, and 40 Most Influential Women.