By Joseph Zompetti & Molly Kerby | Since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, attacks on the media have been relentless. “Fake news” has become a household term, and repeated attempts to break the trust between reporters and the American people have threatened the validity of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In this article, the authors trace the development of fake news and its impact on contemporary political discourse. They also outline cutting-edge pedagogies designed to assist students in critically evaluating the veracity of various news sources and social media sites.

Author Note

Joseph Zompetti, School of Communication, Illinois State University; Molly Kerby, Department of Diversity and Community Studies, Western Kentucky University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Joseph Zompetti, Professor, School of Communication, Illinois State University, Fell Hall 413, Normal, Il 61790-4480. Phone: (309) 438-7876. E-mail: jpzompe@IllinoisState.edu

In 2016, the Oxford English Dictionary labeled post-truth as its word of the year (Oxford Dictionaries, 2018), maintaining that this word, more than any other, reflected the state of the times, since “objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2018). Long gone are the days when a U.S. senator is likely to say, as did Patrick Moynihan in 1994, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts” (as cited in Okrent, 2006, p. 85). In fact, today we are much more likely to hear a political candidate say, “There’s nobody that has more respect for women than I do” (Krieg, 2016) or “I am the least racist person that you have ever met…. And you can speak to Don King, who knows me very well. You can speak to so many different people” (Scott, 2016). These statements by Donald Trump should come as no surprise. After all, in his 2009 book, Trump wrote:

One of the things I’ve learned about the press is that they’re always hungry for a good story, and the more sensational the better…. The point is that if you are a little outrageous, or if you do things that are bold or controversial, the press is going to write about you…. That’s why a little hyperbole never hurts. I play to people’s fantasies … people want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular. I call it truthful hyperbole. It’s an innocent form of exaggeration—and a very effective form of promotion. (Trump, 2009, p. 98, emphasis added)

Since the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump has not abated his use of truthful hyperbole.

Thanks to the type of media attention the election drew, current political communication is replete with what is now known as “fake news.”

On the one hand, Donald Trump has taken to the social media platform Twitter to post the words fake news at least 260 times since June 2015 (Trump Twitter Archive, n.d.). For Trump, fake news refers to accounts, reports, and media attention with which he disagrees. On the other hand, there was a surge of actually fake—as in fabricated or false—news during the 2016 election season. Fictional stories with headlines like “Pope Francis shocks world, endorses Donald Trump for president” and “Ireland is now officially accepting Trump refugees from America,” along with 140 other concocted stories from a small town in Macedonia, were posted at least two million times on Facebook alone (Ritchie, 2016). Undoubtedly, the words—as well as the concept of—fake news have not only entered the daily lexicon, but also come to dominate the way individuals now perceive political discourse.

As a result, in this article we attempt to provide a brief explanation of so-called fake news and offer an example of how we incorporate discussions about fake news into our classes and campuses. Although we are scholars in different but related disciplines, we discovered that our approaches to the contemporary issue of fake news are remarkably similar. We both teach at medium-sized universities, and we are both extremely concerned with how individuals can now readily dismiss facts, even reality, when they do not conform with a person’s beliefs. We hope that our pedagogical approach to critical thinking helps to reduce this problem; however, we also hope, through this article, to contribute to the growing body of scholarly knowledge about fake news and its relevance to citizenship. We find Trump’s notion of fake news and the actual fabrication of fake news to be related: Trump dismisses news that fails to align with his sense of reality, and fabricated news is sometimes manufactured when people need to create stories to combat true news that does not support their perspectives. In this way, our discussion here centers primarily on the definition of fake news as involving factual stories that are labeled “fake” because they do not correspond to the reality of certain individuals. Before discussing how we approach fake news at our universities, however, we first discuss in more detail the nature of fake news and consider some theoretical musings to help readers better understand this phenomenon.

The Nature of Fake News

We have already noted the frequency of Trump’s use of the term fake news. Trump has repeatedly called mainstream media—with the exception of Fox News—fake news, particularly when referring to NBC, CNN, and the New York Times (Seipel, 2018). Recently, in a tweet, Trump even went so far as to characterize the mainstream and cable media as national threats: “Our Country’s biggest enemy is the Fake News so easily promulgated by fools” (as cited in Seipel, 2018). Unquestionably, as the frontrunner for the Republican Party during the 2016 election and now as president, Donald Trump has made the term fake news a normal part of the American vocabulary. When the president of the United States can dismiss reports with which he disagrees, then the rest of us have permission to model this type of behavior. This, of course, calls into question the very nature of “truth.” In other words, if something does not conform with one’s sense of reality, they can easily discount it as fake news and then proceed with their ideological agenda (Bartlett, 2017).

As academics, we are interested in why fake news is now, seemingly all of a sudden, such a hot topic. After all, the political manipulation of facts to fit a particular agenda is not new to American politics. For instance, the fabricated story about the USS Maine started the Spanish-American War, the Tonkin Gulf incident triggered the United States’ incursion into Vietnam, and the nation has experienced historical moments of so-called “yellow journalism” and “jazz journalism” (Kavanagh & Rich, 2018). Furthermore, fake news is not new to the international political scene. Most notably, during World War II, the Nazis characterized foreign enemy news accounts as “Lügenpresse,” or the “lying press,” which simply meant “enemy propaganda” (Griffing, 2017). Indeed, one can mark definitive moments in history when public officials have labeled opposing news reports as “lying,” “fake,” “false,” or “sensational.” At other times, it has been apparent when and how the media and political elites have manipulated news accounts of particular events in order to craft situations that justified their ideological agendas.

Yet, unlike previous variations, fake news today is unique in that there exists a 24/7 news cycle combined with news posted instantaneously on social media from a limitless number of sources. In other words, anyone can report a news story on social media, rendering previous standards for ethical journalism or an expectation of credible expertise nonexistent. The constant news cycle also puts pressure on journalists and news-reporting citizens to report events as quickly as they can. Media sources are rewarded for acquiring the “scoop” on a story, even when all of the facts around that story have not been corroborated. The veracity of such stories is typically not questioned because the speed at which they are reported is of primary importance to producers and consumers of news information. Kavanagh and Rich (2018) suggested other factors contributing to the rise of fake news, such as the “competing demands on the educational system that limit its ability to keep pace with changes in the information system,” and the “political, sociodemographic, and economic polarization” that seems to plague contemporary political discourse (p. xiii-xv).

While all of these elements add cumulatively to the atmosphere of fake news, we want to expound briefly on two other theoretical concepts that help perpetuate fake news. First, most individuals dislike being wrong, and so they naturally seek information that corresponds with their predispositions. According to this theory, known as “motivated reasoning” (McIntyre, 2018), people are motivated to find like-minded information sources that justify their beliefs. Their penchant for wanting to know or believe certain things opens them up to media influence. As McIntyre (2018) argued:

If we are already motivated to want to believe certain things, it doesn’t take much to tip us over to believing them, especially if others we care about already do so. Our inherent cognitive biases make us ripe for manipulation and exploitation by those who have an agenda to push, especially if they can discredit all other sources of information. (p. 62)

It is also known that cognitive dissonance reinforces political thinking—that is, when individuals believe something, they dislike hearing alternative explanations (Festinger, 1957). Similarly, when people only expose themselves to media sources that correspond to their political ideology, then such information confirms their belief system, a phenomenon known as “confirmation bias” (Nickerson, 1998). This behavior is difficult to challenge because it relies less on cognitive processing and more on emotional inclinations. As Cooke (2018) noted:

One of the hallmarks of the post-truth era is the fact that consumers will deliberately pass over objective facts in favor of information that agrees with or confirms their existing beliefs, because they are emotionally invested in their current mental schemas or are emotionally attached to the people or organizations which the new information portrays. The affection dimension of information-seeking and usage circumvents the cognitive processes of information-gathering and selection. (p. 7)

In this way, not only are individuals psychologically prone—if not primed—to seek ideologically consonant information, but their beliefs are also reinforced by such information sources.

Second, motivated reasoning and confirmation bias are also exacerbated by the presence of social media. Bartlett (2017) explained:

The Internet and social media have made it very easy to peddle and promote lies…. [W]hen people who have been exposed to lies are confronted with the truth, they often believe the lie even more strongly. One reason is that simple repetition of a lie even in the course of refuting it, lends it credibility. Another reason is confirmation bias—people believe what they want to believe. (p. 97)

With a multiplicity of information sources from which to choose, individuals can self-select the information they want to receive, leading to the creation of “information silos” or “echo chambers” because their beliefs and the information they receive are in constant alignment without any threats from contrary sources (Lencioni, 2006; Papacharissi, 2010; Sanger, 2013). Given the current political polarization in the United States, “Americans increasingly tend to see their news through prisms of red and blue—to seek confirmation of their existing beliefs, rather than information that might contradict or complicate them. We often gravitate to sources aligned with our own biases and partisan leanings” (Miller, 2016, p. 276). In other words, most Americans live in their own information bubbles that are impervious to external and different perspectives. Of course, on the occasion when one does experience contrasting political information, they can easily dismiss it and resort back to their bubble by labeling the divergent views as fake news. With social media, self-selecting one’s echo chamber of choice is far too easy—and it shows. According to McIntyre (2018):

In a recent Pew poll, 62 percent of U.S. adults reported getting their news from social media, and 71 percent of that was from Facebook…. The result is the well-known problem of “news silos” that feed polarization and fragmentation in media content. If we get our news from social media, we can tune out those sources we don’t like, just as we can unfriend people who disagree with our political opinions. (p. 94, emphasis in original)

Simply put, “there is a growing tendency to obtain news only from sources favorable to one’s ideological or partisan point of view” (Bartlett, 2017, p. 2).

In these ways, while fake news as a concept is not new, recent experience of and exposure to it seems unique. As a result of the prevalence of social media and a diversity of news sources, the instances of fake news—and the opportunity to label news sources as fake—have become pervasive. The frequent use and labeling of fake news is a serious cause for concern. For example, we know that a gunman who shot up a pizza restaurant was motivated and inspired by fake news alleging that the restaurant was involved in a sex trafficking ring orchestrated by Hillary Clinton (Davis, 2016; Debies-Carl, 2017; Hennefield, 2017). Additionally, fake news could even be a trigger for war. According to McIntyre (2018):

A few weeks after “pizzagate,” the Pakistani defense minister threatened nuclear retaliation against Israel as a result of a fake news story he had read that said “Israeli Defense Minister: If Pakistan sends ground troops to Syria on any pretext, we will destroy their country with a nuclear attack.” If the Spanish-American War was started by fake news, is it so outrageous to think that another war could be too? Where might this stop? Fake news is everywhere. (p. 111)

We also know that foreign entities, like Russia, can use fake news to manipulate elections, thereby seriously threatening democratic systems (Blake, 2018; Zarate, 2017). Moreover, fake news can, of course, erode individuals’ understanding of source credibility, challenge the veracity of academic studies and reports, and heighten interpersonal disagreements that center on faulty premises and inaccurate information.

Therefore, as teachers and scholars, we are deeply concerned about the state of affairs concerning fake news. We teach classes that encourage and require students to conduct serious academic research—a process that is obviously complicated by fake news. We also are concerned about the nature of free speech on campuses and the toxic environment that fake news produces in political discourse. Hence, we have attempted to implement strategies for combating the nature of fake news at our respective universities.

A Pedagogical Approach to Fake News on Campus

While modern political campaigns and debates have become a crucial part of the

U.S. electoral process, the broadcasting and reporting of these events has drastically changed. Traditional-aged students are more likely to view elections through social media rather than major television networks or print magazines and newspapers. Unfortunately, social conflict, public debates, propaganda, and fake news impede the process of civil dialogue and blur the lines of legitimate democratic discourse. In addition, recognizing misleading or false information can be difficult for students and is not limited to the political arena. Finding fact-based information for school projects, reports, and analyses can be challenging for young learners as well (McGrew, Ortega, Breakstone, & Wineburg, 2017; Wintersieck, 2017).

In order to combat the consumption and dissemination of ambiguous, distorted, or deceptive communication, information and civic literacy must be embedded in educational pedagogy, especially in higher education. One notable endeavor is the innovative online project known as the Digital Polarization Initiative, or DigiPo, created by Mike Caulfield at Washington State University Vancouver and sponsored by the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) as part of its American Democracy Project (ADP). The methods of the project focus on assessing the credibility of Internet sites, including but not limited to online news outlets, academic journals, and viral photos. The initiative teaches students to think critically, process information contextually, and develop effective civic literacy strategies (AASCU, n.d.).

Another related endeavor, Deliberative Dialogues, focuses on two distinct processes: effective deliberation and cooperative dialogue. The most vital piece in understanding the concept of deliberative dialogue is defining its two correlated yet unique components. According to Heath, Lewis, Schneider, and Majors (2017), “dialogue is the microcommunication practice enacted in public dialogue and is more than just the back and forth exchange of conversations” (p. 3). Authentic dialogue requires active listening, understanding group dynamics related to power and privilege, communicating factual data, and engaging in respectful negotiation. It does not comprise superficial discussion, debate, or aggressive conversation. Further, related to the notion of cooperative dialogue, participants in this form of communication must employ critical thinking and reasoned argument, or effective deliberation, as a means of creating mutual understanding for the public good. The marriage of these two concepts then creates a type of public conversation that aids in building community relationships, solving public problems, and addressing social policy concerns (McCoy & Sully, 2002). DigiPo and Deliberative Dialogues serve as the foundation for two courses at a large, comprehensive university in southcentral Kentucky.

Fake News and Civil Discourse

The course “Fake News and Civil Discourse” is offered as part of an undergraduate minor in citizenship and social justice in the university’s Department of Diversity and Community Studies and as an elective in the Colonnade Program, the university’s general education curriculum. The Colonnade Program is organized into three sections. The first section, Foundations (18 credit hours), centers on practical skills courses in English, math, history, and communication. The second section of the program, Explorations (12 credit hours), focuses on introductory-level courses in cultural, social, behavioral, physical, and natural sciences. The third and final section, Connections (9 credit hours) is dedicated to interdisciplinary courses in social responsibility (social and cultural), global issues and reasoning (local to global), and understanding complex interconnections (systems). To be eligible to take courses in the Connections section, students must complete the Foundations coursework and at least 30 earned credit hours at the university.

Fake News and Civil Discourse examines social and political conflicts that are particularly prone to fake news and discourse, and explores strategies promoting civil dialogue and informed democratic engagement from a systems perspective. The core content is divided into three parts: (a) First Amendment rights, definitions, and DigiPo; (b) Deliberative Dialogues; and (c) analysis, synthesis, and application. Each component of the course speaks continually to contemporary challenges around civic literacy, information literacy, and research sills. The student learning outcomes (SLOs) for the class are as follows:

- demonstrate basic knowledge and interpretations of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution;

- categorize sources of news and information;

- evaluate public discourse rooted in social media;

- formulate a cohesive argument using the principles of civil discourse; and,

- synthesize a news pattern and propose alternative solutions for creative civil conversations.

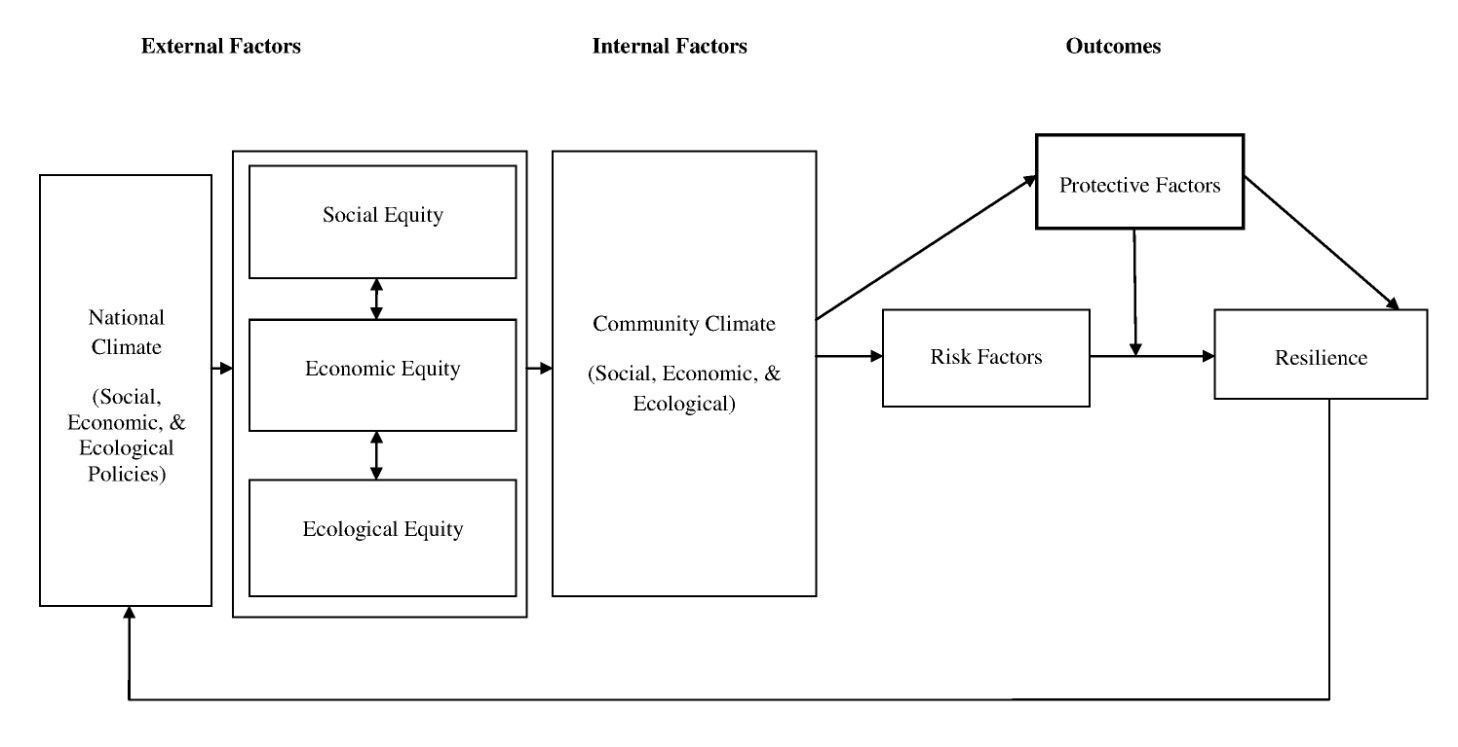

The foundation of the course is based on a previously constructed path model of organizational sustainability derived from the conceptualization of systems thinking (Figure 1; Kerby & Mallinger, 2014). The model in Figure 1 depicts the interconnectedness of the national climate on social, economic, and ecological equity, and demonstrates the causal relation between the external and internal factors related to the resilience of a particular organization, group, issue, etc. The model has utility for developing systematic views of public issues that begin with national climate and the imbalance of power (external factors). The external factors directly affect the climate of communities and organizations within the system (internal factors). The impact of the external factors on the internal factors produces factors that put the system at risk of failure or endanger the possibility of resilience. Figure 1 illustrates a general application of adaptive protective factors in the larger community. The paths from internal factors to protective factors emphasize the mediating or moderating effects on resilience (Kerby, Branham, & Mallinger, 2014).

Figure 1. Theoretical model of resilience.

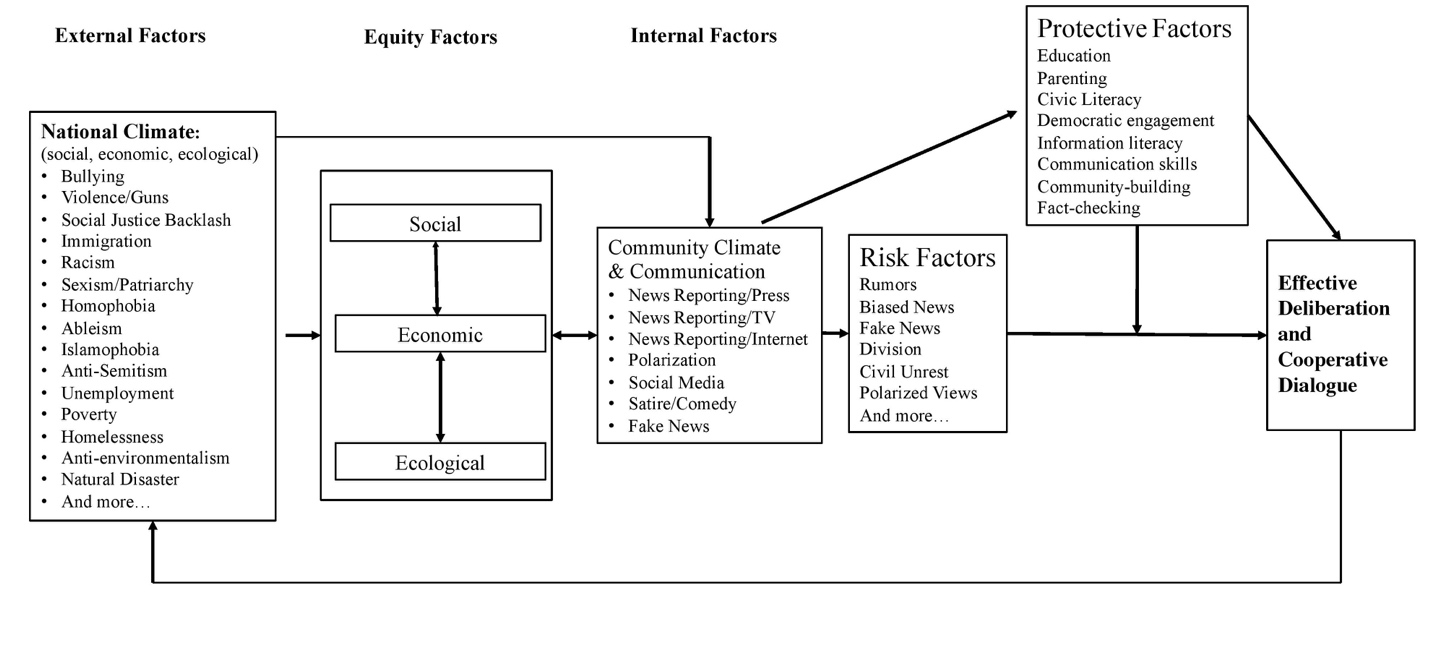

This general model was adapted specifically for the pedagogical design of the course (Figure 2). The external and internal factors (i.e., national climate, equity, and community climate) shaped the first half of the class. Students explored contemporary issues and debates in terms of current national climate as well as the historical context (First Amendment rights, Jim Crow laws, McCarthyism, etc.). Using DigiPo’s online text—Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers (Caulfield, 2017)—students investigated the validity of news and media, communications with a concentration on social justice-themed reports subject to political biases, misinformation, and false reporting (e.g., Black Lives Matter). All assignments were drawn from Caulfield’s (2018) lessons blog, Four Moves: Adventure in Fact-Checking for Students: (a) check for previous work (i.e., has someone else fact-checked the information, (b) go “upstream” (i.e., find the original source), (c) read laterally (i.e., read what other people say about the source), and (d) circle back (i.e., if you get lost, start over with a different path).

Figure 2. Theoretical model adapted for the course “Fake News and Civil Discourse.”

The second part of the course focuses on the particular risk factors associated with the delivery and dissemination of deceptive, fallacious, and bogus information, as well as the mediating and/or moderating protective factors that lead to effective deliberation and cooperative dialogue (see Figure 2). In order to practice skills learned in the course, students participate in a coordinated deliberative dialogue with a class in the Department of Social Work concerning U.S. immigration called “Coming to America: Who Should We Welcome, What Should We Do?” In past semesters, materials for the dialogue were gathered from the National Issues Forums Institute (NIFI), a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes public deliberation around difficult issues. NIFI also publishes free issue guides and materials that encourage collaboration and civil discourse (NIFI, n.d.). The goal of this exercise was for students to evaluate the nature of public discourse rooted in social media and to formulate a cohesive argument using the principles of civil discourse.

The last part of the course is devoted to synthesizing controversial news patterns and proposing alternative solutions for creative civil conversations. For the final project, students work in groups to create issues guides (similar to those published by NIFI) on a social justice topic prone to fake news. Topics identified by the groups range from the legalization of medical marijuana to drones and counter-terrorism. Each group is required to generate a 25- to 30-page, long-form guide that included historical data, contemporary research on positions, and three detailed optional solutions. In addition to the long form, groups are instructed to provide a shorter (two to three pages), quick-view PDF version of the guide listing the possible solutions, a guide sheet for dialogue moderators, and an outcomes assessment protocol. In place of a final exam, the student groups conduct a one-hour deliberative dialogue with classmates on the topic chosen for the project. The final assessment includes an instructor grading rubric as well as a peer review.

Although this course is entirely devoted to the issue of fake news, the materials can be used in smaller portions of any course. In this example, the social work course only participated in the deliberative dialogue for two class periods, and the dialogue used to supplement the topic of immigration being discussed. Caulfield’s (2017) text also includes a chapter on evalutating the impact factors of journal articles, for example, which can be used to introduce the topic of research in any course.

Controversy in Contemporary Society

We also teach another course called “Controversy in Contemporary Society.” In this course, we train students how to construct an argument based on the Toulmin model (i.e., a claim represents the sum of evidence plus reasons), identify argument fallacies, locate rhetorical strategies, and understand different types of rhetorical spin as they occur in domestic political discourse. The SLOs for the course include the following:

1. know what a “wingnut” is and how it functions in contemporary U.S. culture;

2. understand different theoretical perspectives for analyzing wingnut rhetoric;

3. develop skills in using theory to analyze the texts of wingnuts;

4. articulate ideas in both oral and written contexts concerning the wingnut rhetoric;

5. discuss issues pertaining to wingnuts in civilized discourse; and,

6. construct arguments about the significance of wingnut rhetoric.

By framing the course around Avlon’s (2014) notion of wingnuts (i.e., partisan extremists who dominate and polarize political discourse) the course examines the types of rhetorical techniques used by divisive rhetorical figures. Students must write two papers in the course—one that examines a conservative rhetor of the student’s choosing and one that analyzes a liberal rhetor—and for each paper the student must identify, interpret, and explain the significance of the polarized rhetorical strategies used by the rhetor that could classify them as a wingnut. Students also read Zompetti’s (2018) text, Divisive Discourse: The Extreme Rhetoric of Contemporary American Politics, as a way of exploring how polarized rhetoric emerges in significant current, controversial issues such as immigration, gun control, race relations, religion, health care, LGTBQ+ rights, etc. In this way, any instructor could take a controversial and contemporary topic and then frame that issue as a discussion topic. The idea is to present to students extreme polarities and then ask them to discuss why the ideas are extremes—thereby hopefully understanding the viewpoints of others and even, quite possibly, finding room for compromise.

In both cases, we teach these courses to improve our students’ skills in critical thinking, advocacy, and media literacy. By teaching research from multiple perspectives, critical thinking, and how to construct arguments, we attempt to provide students with opportunities to be exposed to multiple news sources and to determine the veracity of each of those news perspectives. Our hope is that these two pedagogical examples illustrate how the concept of “fake news” is addressed in meaningful and useful ways for our students.

Conclusions and Implications

The advent of new technologies brings with it the need to examine information literacy and communication in different ways. Referring back to Figure 1, resilient organizations integrate external and internal systems in hopes of creating seamless transformations and competitive climates that reach beyond top-down management. Decisions and problem-solving strategies emanate from the notion of logical vertical integration and cooperation rather than from a small number of representatives in upper management. Members of the organization are consequently empowered to lead efforts that generate fresh ideas and lead to effective ways of producing positive outcomes (Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, Castek, & Henry, 2017).

Figure 2 also helps readers to understand the impact of the national climate and inequities concerning the way Americans communicate news and events to the masses. The more inflammatory the story, the more vulnerable democracy becomes. Extremist groups and international hackers, for instance, have systematically spread disinformation, rumors, and falsehoods through social media and the Internet in order to undermine the political landscape, polarize citizens, and interfere with election results. Such fallacious stories thrive in an environment where critical thinking, media and information literacy, and basic civic education are deficient. The results of this phenomenon have been devasting to culture and society as a whole. The bedrock of American democracy has always been its unique amalgamation of empathic understanding, sound reasoning, tempered patriotism, and pride in citizenship. While none of these traits has disappeared, they are all being challenged at every junction (Reynolds & Parker, 2018).

In addition to illustrating the conceptual framework of resilience, Figures 1 and 2 are purposely constructed for assessment. Notably, our courses cover fact-checking news and media, civic and information literacy, library research skills, and construction of deliberative dialogues. Since most courses do not have time to teach all of these skills in addition to content, our goal is to determine which proficiencies contribute to greater competence around debunking misleading information. Our first course example is part of a cross-sectional study (which includes several other courses) examining various pedagogical methods aimed at information and civic literacy education. Similarly, our second example has been evaluated as part of a larger political engagement assessment; the finding of this assessment have indicated that our students’ political knowledge, attitudes, and skills have statistically improved without altering students’ political ideologies (e.g., Hunt, Meyer, Hooker, Simonds, & Lippert, 2016). This means, of course, that our class has contributed significantly to teaching skills, such as critical thinking and identifying fake news, while not indoctrinating students ideologically.

Our educational institutions have unfortunately been negligent in addressing the challenges facing the future of today’s young people. Recent studies have indicated that students often graduate from universities with little knowledge of civic and information literacy or the ability to determine the validity of online resources (Crenshaw, Delgado, Matsuda, & Lawrence, 2018; Francis, 2018; Huda et al., 2018). As a pedagogical approach to holistic liberal arts education, faculty and administrators in higher education must take seriously the need to produce informed citizens who have skills beyond task-orientation. While the first example illustrated in this article is elaborate and spans the entire course, creating space for students to learn skills in deliberation and fact-checking does not have to be time-consuming or complex. An ideal place to start is general education. Designing universal, required courses that explore online communication, critical thinking, and information literacy, and that focus on argumentation and deliberation can help students apply these acquired skills to major programs of study. After all, the more contemporary goal of the American university is to prepare global citizens who can think critically, solve complex problems, and participate fully in the nation’s political, social, and economic processes.

Of course, we recognize the challenges of developing and implementing new courses, particularly at the general education level. Such a move requires additional faculty and resources, stakeholder buy-in, and classroom scheduling, to name only a few. Institutions, however, should understand the significant problems underlying the nature of fake news and take measures to combat it. At the very least, individual departments and faculty members should devote courses, exercises, colloquia, and other pedagogical opportunities to improving critical thinking and information literacy skills. Colleges and departments should also support and promote faculty development in these areas. At a minimum, instructors can incorporate readings, exercises, assignments, etc. into their existing syllabi and curricula to heighten awareness of fake news in their classrooms. In other words, we firmly believe that the phenomenon of fake news demands significant and concentrated attention in higher education. Fake news not only frustrates and erodes the teaching of knowledge, it also jeopardizes the foundation of democracy by undermining the concept of political knowledge itself. As such, educators must take seriously this contemporary hazard. We genuinely hope this article contributes to the conversation around addressing in deliberative ways the menace of fake news.

References

American Association of State Colleges and Universities (n. d.). Retrieved from http://www.aascu.org/AcademicAffairs/ADP/CivicFellows/

Avlon, J. (2014). Wingnuts: Extremism in the age of Obama. New York: Beast Books.

Bartlett, B. (2017). The truth matters: A citizen’s guide to separating facts from lies and stopping fake news in its tracks. New York: Ten Speed Press.

Blake, A. (2018, April 3). A new study suggests fake news might have won Donald Trump the 2016 election. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/ news/the-fix/wp/2018/04/03/a-new-study-suggests-fake-news-might-have-won-donald-trump-the-2016-election/?utm_term=.2676569e93b1

Caulfield, M. (2017). Web literacy for student fact checkers [Creative Commons]. Retrieved from https://webliteracy.pressbooks.com/

Caulfield, M. (2018). Four moves: Adventures in fact-checking for students. Retrieved from https://fourmoves.blog/

Cooke, N. A. (2018). Fake news and alternative facts: Information literacy in a post-truth era. Chicago: ALA Editions.

Crenshaw, K. W., Delgado, R., Matsuda, M. J., & Lawrence, C. R. (2018). Introduction. In Words that wound (pp. 1-15). New York: Routledge.

Davis, W. (2016, December 5). Fake or real? How to self-check the news and get the facts. NPR: All Tech Considered. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/ 2016/12/05/503581220/fake-or-real-how-to-self-check-the-news-and-get-the-facts

Debies-Carl, J. S. (2017). Pizzagate and beyond: Using social research to understand conspiracy legends. Skeptical Inquirer, 41(6). Retrieved from https://www.csicop.org/si/show/ pizzagate_and_beyond

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Berkeley, CA: Stanford University Press.

Francis, C. (2018). Academic rigor in the college classroom: Two federal commissions strive to define rigor in the past 70 years. New Directions for Higher Education, 2018(181), 25-34. doi:10.1002/he.20268

Griffing, A. (2017, October 8). A brief history of “Lügenpresse,” the Nazi-era predecessor to Trump’s “fake news.” Haaretz. Retrieved from https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/1.772836

Heath, R. G., Lewis, N., Schneider, B., & Majors, E. (2017). Beyond aggregation: “The wisdom of crowds” meets dialogue in the case study of shaping America’s youth. Journal of Public Deliberation, 13(2), 3.

Hennefield, M. (2017, February 19). Fake news: From satirical truthiness to alternative facts. New Politics. Retrieved from http://newpol.org/content/fake-news-satirical-truthiness-alternative-facts

Huda, M., Jasmi, K. A., Alas, Y., Qodriah, S. L., Dacholfany, M. I., & Jamsari, E. A. (2018). Empowering civic responsibility: Insights from service learning. In S. Burton (Ed.), Engaged scholarship and civic responsibility in higher education (pp. 144-165). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Hunt, S. K., Meyer, K. R., Hooker, J. F., Simonds, C. J., & Lippert, L. (2016). Implementing the Political Engagement Project in an introductory communication course: An examination of the effects of students’ political knowledge, efficacy, skills, behavior, and ideology. eJournal of Public Affairs, 5(2). Retrieved from https://ejopa.missouristate.edu/ index.php/ejournal/issue/view/Educating%20for%20Democracy

Kavanagh, J., & Rich, M. D. (2018). Truth decay: An initial exploration of thediminishing role of facts and analysis in American public life. Washington, DC: Rand Corporation.

Kerby, M. B., & Mallinger, G.M. (2014). Beyond sustainability: A new conceptual model. eJournal of Public Affairs, 3(3). Retrieved from http://ejopa.missouristate.edu/ index.php/ejournal/article/view/38/47

Kerby, M. B., Branham, K. R., & Mallinger, G. M. (2014). Consumer-based higher education: The uncaring of learning. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 14(5), 42-54.

Krieg, G. (2016, October 7). 12 times Donald Trump declared his “respect” for women. CNN Politics. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2016/10/07/politics/donald-trump-respect-women/index.html

Lencioni, P. (2006). Silos, politics and turf wars: A leadership fable about destroying the barriers that turn colleagues into competitors. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leu, D. J., Kinzer, C. K., Coiro, J., Castek, J., & Henry, L. A. (2017). New literacies: A dual-level theory of the changing nature of literacy, instruction, and assessment. Journal of Education, 197(2), 1-18.

McCoy, M. L., & Scully, P. L. (2002). Deliberative dialogue to expand civic engagement: What kind of talk does democracy need? National Civic Review, 91(2), 117-135.

McGrew, S., Ortega, T., Breakstone, J., & Wineburg, S. (2017). The challenge that’s bigger than fake news: Civic reasoning in a social media environment. American Educator, 41(3), 4-9.

McIntyre, L. (2018). Post-truth. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Miller, A. C. (2016, June 25). Confronting confirmation bias: Giving truth a fighting chance in the information age. Social Education, 80(5), 276-279.

National Issues Forums Institute (n.d.). About National Issues Forums Institute. Retrieved from https://www.nifi.org/en/about

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175-220.

Okrent, D. (2006). Public editor number one: The collected columns (with reflections, reconsiderations, and even a few retractions) of the first ombudsman of The New York Times. New York: Public Affairs.

Oxford Dictionaries (2018). Word of the year. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016

Papacharissi, Z. A. (2010). A private sphere: Democracy in a digital age. New York: Polity.

Reynolds, L., & Parker, L. (2018). Digital resilience: Stronger citizens online. Retrieved from http://www.isdglobal.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/05/Digital_Resilience_Project_Report.pdf

Ritchie, H. (2016, December 30). Biggest fake news stories of 2016. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/30/read-all-about-it-the-biggest-fake-news-stories-of-2016.html

Sanger, L. (2013). What *should* we be worried about? The Edge. Retrieved from http://edge.org/response-detail/23777

Scott, E. (2016, September 15). Donald Trump: I’m “the least racist person.” CNN Politics. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/15/politics/donald-trump-election-2016-racism/index.html

Seipel, B. (2018, June 13). Trump calls “fake news” the country’s biggest enemy. The Hill. Retrieved from http://thehill.com/homenews/administration/392026-trump-calls-fake-news-the-countrys-biggest-enemy

Trump, D. J. (2009). The art of the deal. New York: Random House.

Trump Twitter Archive (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.trumptwitterarchive.com/archive

Wintersieck, A. L. (2017). Debating the truth: The impact of fact-checking during electoral debates. American Politics Research, 45(2), 304-331. doi:10.1177/1532673X16686555

Zarate, J. C. (2017). The cyber attacks on democracy. The Catalyst: A Journal of Ideas

from the Bush Institute, Fall(8). Retrieved from https://www.bushcenter.org/catalyst/ democracy/zarate-cyber-attacks-on-democracy.html

Zompetti, J. P. (2018). Divisive discourse: The extreme rhetoric of contemporary American politics (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Cognella.

Dr. Joseph Zompetti is professor in the School of Communication at Illinois State University. His teaching and research interests include rhetoric, political communication, critical/cultural theory, and argumentation. He has published in the Western Journal of Communication, Culture Theory & Critique, the Howard Journal of Communication, and has recently published the 2nd edition of his primary book, Divisive Discourse: The Extreme Rhetoric of Contemporary American Politics.

Dr. Joseph Zompetti is professor in the School of Communication at Illinois State University. His teaching and research interests include rhetoric, political communication, critical/cultural theory, and argumentation. He has published in the Western Journal of Communication, Culture Theory & Critique, the Howard Journal of Communication, and has recently published the 2nd edition of his primary book, Divisive Discourse: The Extreme Rhetoric of Contemporary American Politics.

Dr. Molly Kerby is associate professor in the Department of Diversity & Community Studies at Western Kentucky University. She teaches courses relating to organizational change, sustainability, and the social politics of place. As an expert in social science and environmental studies, she has published in premier journals such as the Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, the eJournal of Public Affairs, and the Journal of College Student Retention. She also works passionately for social justice issues and civic engagement in various communities.

Dr. Molly Kerby is associate professor in the Department of Diversity & Community Studies at Western Kentucky University. She teaches courses relating to organizational change, sustainability, and the social politics of place. As an expert in social science and environmental studies, she has published in premier journals such as the Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, the eJournal of Public Affairs, and the Journal of College Student Retention. She also works passionately for social justice issues and civic engagement in various communities.