By Dmitri S. Seals | Intersectional understandings of diversity present a challenge to the traditional pursuit of cultural competency in public affairs, demanding an approach that accounts for the dynamism and internal diversity of cultural categories. Programs aimed at preparing future public affairs professionals to succeed in diverse settings must have pedagogical tools that equip their students to learn from and engage with intersectional cultural difference. This field report analyzes a pilot project in cultural sociology—a sub-discipline rarely associated with public affairs practice—that used discourse analysis, participatory action research, and intersectionality theory to engage students in designing culturally competent programs and policies. Reviewing current models of cultural competency in public affairs to situate a preliminary analysis of course materials, student surveys, and student work, the report develops a toolkit for programs and faculty seeking to enrich public affairs practice with the cultural study of intersectional difference.

Author Note

Dmitri S. Seals, Department of Sociology, California State University, Los Angeles.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Dmitri S. Seals, Lecturer, Department of Sociology, California State University, Los Angeles, 5151 State University Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90032. E-mail: dseals2@calstatela.edu

In their careers as social workers, administrators, educators, and advocates, the next generation of students will serve a population that rarely fits in simple boxes of culture or race. For decades, the staggering complexity of social identification has been clear in global cities where diversity is woven into urban identity, but internal differences flourish in settings and demographic groups once assumed to be homogeneous (Sharp & Lee, 2017). For this reason, cross-cutting identities and intersecting systems of power make any static body of knowledge about the needs, values, and beliefs of racial and cultural groups rapidly obsolete (Carrizales, Zahradnik, & Silverio, 2016; Lopez-Littleton & Blessett, 2015; Norman-Major & Gooden, 2012).

In their careers as social workers, administrators, educators, and advocates, the next generation of students will serve a population that rarely fits in simple boxes of culture or race. For decades, the staggering complexity of social identification has been clear in global cities where diversity is woven into urban identity, but internal differences flourish in settings and demographic groups once assumed to be homogeneous (Sharp & Lee, 2017). For this reason, cross-cutting identities and intersecting systems of power make any static body of knowledge about the needs, values, and beliefs of racial and cultural groups rapidly obsolete (Carrizales, Zahradnik, & Silverio, 2016; Lopez-Littleton & Blessett, 2015; Norman-Major & Gooden, 2012).

College and university programs in social sciences, public affairs, and social work face the danger of falling behind the intersectionality of social reality when they fail to grapple with three major complexities of the social world: multifaceted identities, cultural change, and embedded inequalities. When training sorts people into fixed categories—for instance, helping largely White and privileged groups of medical professionals learn the health beliefs of “cultural others”—it risks essentializing these categories and ignoring multifaceted identities that cut across social boundaries (Sears, 2012). When cultural competency programs emphasize knowledge easily assessed by multiple-choice tests over more complex sets of attitudes, skills, and community relationships, they fail to equip students to update their cultural knowledge as frameworks evolve (Carrizales, 2010). Moreover, when courses treat culture as separate from embedded inequalities of race, class, and other forms of domination, they miss the opportunity to prepare students to use cultural understanding to address the holistic needs of communities (Fisher-Borne, Cain, & Martin, 2015).

In the past decade, scholars across a broad range of fields have begun to bring a much-needed intersectional lens to cultural competency training (Bird, Mendenhall, Stevens, & Oddou, 2010; Garran & Rozas, 2013; Mattsson, 2014). To continue this progress, faculty and trainers will require more than critique and theory. They will need to match ideas to practical pedagogical tools: projects, activities, texts, and course designs that engage and inspire students to unite the theory and practice of intersectional cultural competency. Similarly, students will need not just tools of theory to understand intersectional identities in the abstract but also methodological tools to identify cultural patterns and place them in the context of intersectional forms of domination. To become capable practitioners and leaders in their fields, students will also need to be able to connect their knowledge of culture to reflective interventions that benefit the people they serve and that help to break down boundaries separating service organizations, universities, and communities (Irazabal & Harris, 2011).

This article comprises a field report on a course that used cultural action research to bring together three elements not often seen in combination: intersectionality studies, cultural sociology, and practical efforts to change culture. More descriptive and practically oriented than traditional research, field reports create opportunities for scholarly communities to quickly share and build on innovations together (e.g., Atkinson & Hunt, 2008; Gamson, 2009; Strickland & Strickland, 2013; Williamson, 2017; Wynn, 2009). The subject of this report is an upper-division general education course in sociology called Cultural Emotions, serving mostly non-majors who intend to continue on to careers in nonprofits, schools, and service agencies. Much of the pedagogical literature on cultural competency assumes relatively privileged bodies of students; however, cultural competency is not just for White people (Sears, 2012), and without curriculum crafted for internally diverse classrooms, public affairs programs will only further disempower students from marginalized groups. Thus, the following field report seeks to develop the course as a vehicle for a cultural competency that is dynamic, intersectional, and empowering for diverse students.

Literatures in Dialogue: Intersectionality, Cultural Sociology, and Action Research

In this section, I describe the specific synthesis of literatures that fueled the intersectional cultural action research of the Cultural Emotions course, building toward forms of cultural competency adequate to the diverse and complex contexts of real-world service and advocacy. The primary elements of this synthesis—intersectionality studies, mixed-methods cultural analysis, and action research—are rooted in different disciplines that rarely join forces. Combining practical insights for public affairs from such divergent and complex fields takes work: Each field comprises a dense thicket of terms and concepts that can feel like a new language to students. The following tour seeks to facilitate work at the juncture of these three fields by excavating a set of conceptual tools and approachable readings (the citations in this section) to help faculty and students honor the unique contributions of each set of literature while using them in combination.

The field of intersectionality studies is internally diverse, building from a simple shared insight—that social categories are better understood together than alone—to a broad range of meanings and methods driving intersectional research and action (P. H. Collins, 2015). This internal diversity offers a tremendous teaching opportunity, making it possible for each student to create their own approaches to intersectional analysis as part of a field that “emphasizes collaboration and literacy rather than unity” (Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall, 2013, p. 785). Learning to study culture with an intersectional lens can help students shake free of stereotypical approaches to cultural groups and grapple with how their own complex identities evolve and interact in the context of broad systems of power.

Insights from intersectional analysis have transformed the practice of anti-discrimination law and driven revolutions in social theory. Still, because intersectional approaches embrace complexity, they have sometimes been critiqued as standing in the way of clear methodology for social research or practical intervention for social change (Hancock, 2007; McCall, 2005). Combining intersectional analysis with cultural sociology is one way to address this tension, pushing past the simple insight that categories intersect to reveal how and why those intersections matter (Choo & Ferree, 2010).

Training students to be culturally competent begs a few questions: What is culture? How is it made? What can a culturally competent person do? Any program concerned with cultural competency should engage these questions rigorously, and cultural sociology provides tools for just that. With an intersectional perspective to correct for the historical biases of sociological analysis (Zuberi & Bonilla-Silva, 2008), cultural sociology can point to specific targets for intersectional cultural research and the methods for reaching them clearly. Focusing inquiry on specific concepts—such as schemas, interaction rituals, field-specific cultural capital, and symbolic boundaries—can help students increase the rigor of their critiques and the practical value of their own cultural work.

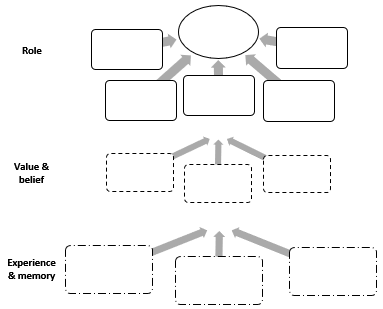

These concepts draw from synthetic research at the interface of cultural sociology, social psychology, and neuroscience that explores processes of inclusion and exclusion in the formation of stereotypes (Amodio, 2014), ideologies (Jost, Federico, & Napier, 2009; Jost, Nam, Amodio, & Van Bavel, 2014), and identities (Hogg, 2016). Central to this literature is the concept of schemas: networks of linked symbols that carry meaning (Sewell, 2005). When an individual interprets symbols in combination—for instance, as you read the individual words of this sentence in succession—those symbols associate, building links that accumulate and ultimately form durable networks that guide one’s interpretation, identification, and action (Lakoff, 1987). The value of schemas for cultural competency training lies in enabling students to see the formation of culture in daily experience, as complex schematic constructs like roles, scripts, and frames take shape from simpler building blocks like symbols, beliefs, and values (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Course slide showing how schemas interconnect across levels of complexity (e.g., symbols aggregate in institutions, which then create and circulate new symbols).

Cultural sociology also contributes a set of specific mechanisms that can help students pinpoint how and why culture is relevant to embedded inequality, prejudice, and social justice. Engaging with the concept of stratified interaction rituals can help students identify the specific aspects of momentary interactions across cultural difference that can charge moments with deep and lifelong emotional impact (R. Collins, 2014). To understand how these moments relate to systems of economic and power inequality, students can identify cultural capital—valued schemas that reference and reinforce material inequality, which appear in interaction and in text (Bourdieu, 1991)—specific to the institutional and social contexts they are studying. Through careful analysis of interaction and discourse, students can trace cultural capital along with symbolic boundaries, revealing how people use language and symbols to define and evaluate in-groups and out-groups (Lamont, 2012).

For students headed toward a career in public affairs—or any career that requires understanding the values, beliefs, and needs of other people—intersectional cultural research offers a crucial toolkit for understanding the complex needs and identities of clients. In their primer on intersectional research in cultural sociology, Choo and Ferree (2010) made clear how this research disrupts and reforms established patterns of action: An intersectional lens challenges researchers to center multiply-marginalized groups in the analysis, highlights interactions among social categories, and reveals institutions and relationships in the context of larger forces. Still, cultural sociology is most closely connected to practical work through social movements, particularly in a line of research focusing on how movements create and deploy cultural frames to create emotional resonance and mobilize members (Ferree, 2003; Goodwin, Jasper, & Polletta, 2009; Jasper, 2017). More recently, a parallel line of research has opened into institutional culture (Armstrong & Bernstein, 2008; Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2012), tracing specific schemas, routines, and policies that reinforce inequality and opening a bridge to intersectional studies of institutional diversity (Ahmed, 2012).

The complementary strengths of intersectional studies and cultural sociology reveal themselves best in real-world application; participatory action research is an ideal framework to help students connect cultural analysis to practical cultural competency. Generally, action research situates observation and data collection in the context of a cycle of reflection and engagement; observation leads to critical reflection in which students question and test their assumptions and interpretations; reflection informs a plan of action; and action fuels more observation and critical reflection (McNiff, 2013). Action research has proven to increase student engagement and concept retention (Gibbs et al., 2017), especially when team-based (Saldivar, 2015), and some scholars have proposed it as a crucial tool in reclaiming the public function of universities (Levin & Greenwood, 2016).

Crucially, participatory action research challenges students to practice cultural humility, challenging their own beliefs and values in dialogue with the communities they serve (Fals Borda, 2013). Action researchers design methods for the systematic critique and transformation of institutions, answering calls to question dominant cultural practices, center the perspectives of marginalized communities, and tear down institutional barriers to their advancement (Fisher-Borne et al., 2015). Informed by cultural sociology and complicating culture with an intersectional lens, participatory action research can help students perform precisely the kind of reflective intervention that culturally competent professionals should display.

Course Design: Cultural Competency in Cultural Emotions

The Cultural Emotions course discussed here supports and relies on two movements at California State University, Los Angeles (Cal State LA). The first is a movement of students and faculty for more robust diversity training, specifically highlighting intersectionality along with intercultural and intracultural relationships. In 2014, their efforts engendered a stream of courses and graduation requirements on diversity, civic learning, and community engagement across the university (Flaherty, 2014). The second movement is the Civic and Social Innovation Group (CaSIG) at Cal State LA, a collective of professors developing change-oriented courses in sociology, political science, and education.

Drawing from these movements, the evolution of the Cultural Emotions course has mirrored the evolution of cultural competency training: It was created in the vein of 1990s multiculturalism, exploring questions such as how people in China and Africa experience joy, but has been retooled in recent years to focus on racial and cultural inequality. When I began teaching sections of the course, I first combined only intersectionality and cultural sociology, emphasizing original research without engaging the question of how to change culture. The course earned high student reviews, but it was clear that even—and especially—the most engaged students were frustrated to have gained all this cultural knowledge without a clear way to put it into practice. The combination of engagement and frustration was a strong motivator to incorporate action research and to enable students to connect more strongly to local practitioners and communities.

The diversity of students at Cal State LA makes the university a natural site for creating models for intersectional cultural competency. The students the university serves are predominantly first-generation students of color, with over half identifying as Hispanic or Latinx but representing a broad diversity of ethnic and family backgrounds (Contreras & Contreras, 2015). The juniors and seniors who take the Cultural Emotions course generally come from a wide spectrum of social science and public service majors and follow a range of paths leading them to careers in schools, public health, and government service. Cal State LA is a commuter college, primarily serving students from Los Angeles County, but Los Angeles is the most populous county in the United States, and the backgrounds and neighborhoods of students vary widely. For instance, one team focusing on the cultural dynamics of gentrification and neighborhood change included a Latino student from East Los Angeles, an Armenian student from Glendale, and an African-American student from Hollywood.

The Cultural Emotions course activates concepts from cultural sociology and intersectional studies by embedding classroom learning in community-based cultural action research. Every week, students both engage readings and take a step forward in a capstone project called Research to Action, in which teams of students design a strategy for cultural change based on participatory action research, moving through phases of observation, reflection, and planning for action. Through each phase, their ongoing cultural action research proceeds in dialogue with readings and thematic explorations (see Table 1). The project culminates in a Strategy Summit in which groups present plans for change that fight cultural inequality, heighten cultural competency, and engage an audience of peers, practitioners, and community members.

|

Phase (Weeks) |

Cultural Action Research |

Readings and Themes |

Assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Observation to reflection (1-6) |

Conceptual and historical exploration; quantitative survey; qualitative interviews |

Measuring culture and emotion; identity and symbolic boundary; emotion, decision, action; institutions and fields |

Needs and strengths assessment; midterm synthetic essays |

|

Reflection to planning |

Form groups and harmonize approaches; craft solutions; get guidance and feedback |

Scales of inequality and change from micro to macro; culture in institutions, organizations, movements |

Final synthetic essays; draft strategy proposals |

|

Planning to action |

Synthesize readings and feedback; finalize proposals; advocate; connect to practitioners |

Case studies and themes: body and identity: race, class, and gender; economy and choice; bridges and coalitions |

Strategy proposal; Strategy Summit; individual reflection |

Table 1. Interplay of Cultural Action Research with Readings, Themes, and Assessments

This mixed-methods research starts with students designing a quantitative survey together as a full course group. Building from analysis of the survey data, students prioritize a set of generative themes and individually design and conduct five or more qualitative interviews in their own communities; in the terms of Hollinsworth (2013), these interviews “ask for an autobiography” to initiate cultural learning. To bring specificity to this learning, each student designs their interviews to reveal schemas, writing questions and probes to identify specific beliefs, values, symbols, and practices in the lives of their friends, family, and neighbors. The students gather into thematic teams, compiling and synthesizing their interview data to create Needs and Strengths Assessments. These writings outline both cultural inequalities and opportunities and resources to support positive change. The teams’ choice of titles traces their interest in intersectional analysis: Hispanics in the LBGT Community; Cultural Struggles for Latinx College Students; Workplace Culture in Businesses Owned by Women; White Males and Entitlement.

Drawing from this cultural research, teams work together in consultation with their interviewees to design and refine proposals for cultural change. They create a draft strategy proposal, each student taking the lead on one of four sections: They refine their analysis of cultural challenges in the Needs section; map community resources in Strengths; propose a cultural intervention and a plan to sustain cultural change over time in Model; and articulate a long-term vision tied to short-term benchmarks in the final Impact section. Over the final five weeks of the course, as they explore case studies and special themes, groups evolve their proposals in response to several rounds of feedback—first to their peers and the participants in their qualitative interviews, then to their professor, and finally to local practitioners and community members.

Every student completes a set of final exam essays requiring them to synthesize concepts in practical contexts, but the capstone of the course is the Strategy Summit during which they present their proposals in public, demonstrating cultural competency gained through cultural action research. The event brings together a range of professionals, family, and community members to engage and celebrate students as they present their respective strategies from needs and strengths to model and impact. The faculty in the CaSIG at Cal State LA all hold similar events with shared goals: (1) to share substantive ideas to help real people and communities; (2) to improve the quality of student work with clear real-world stakes of learning; and (3) to build lasting connections between and among students, practitioners, and community members. Faculty encourage students to use these events to build their networks as professionals and agents of change, and they encourage community partners to come; as a result, it is not uncommon for students to leave a Strategy Summit with internships and job opportunities.

There is no formal requirement to put models in action—just extra credit—but many teams create a pilot project to test their strategy in the context of the institutions and communities they aim to serve. For instance, one group interested in education designed a program to help undocumented students thrive at their old high schools, studying the institutional culture of their schools, identifying a coalition of allies through their interviews, and creating a set of support materials to change the perception of these students on campus. Another team crafted a plan to assist nonprofits with their social media presence as part of a campaign to fight stigma against homeless people; one student parlayed that plan into a social media position at one of the nonprofits. In each case, intersectional analysis strengthened cultural analysis, complicating easy answers and requiring interventions to be dynamic and to adapt to the needs and strengths of specific contexts.

Practical Tools: Activities, Readings, and Routines

Because this course moves quickly through topics, it relies on a relatively stable weekly routine to create clear expectations and a sense of consistency. The week begins with a conceptual introduction and a close reading of the toughest texts of the week, opening up the authors as subjects of cultural analysis and unpacking the symbols and schemas that matter most to their analysis. Students generally skim the readings before the first meeting and then circle back, engaging them more deeply in posts to the online course forums and in responses to each other’s posts. Each day includes a mix of lecture, group work, and reflective writings, which are graded in the first few weeks as an opportunity to give guidance on quality and then simply become part of the routine.

Generally the week culminates in a practical challenge that references readings and concepts in the context of scenarios students might encounter in their lives as professionals, advocates, and cultural workers after graduation. The following is an outline of three resources I have found helpful along the way.

Intersectional Identity Maps

This early project aims to give students personal experience of how identities form from the intersection of social classifications, aligning with calls to ground the development of cultural competency in critical self-awareness (Chao, Okazaki, & Hong, 2011). Weekly readings are anchored by classic self-analyses of intersectional cultural difference (Anzaldúa, 1987; Montoya, 1994). It begins with an identity breakdown of the professor: I start a list of categories with race, class, and gender, and solicit more, modeling an analysis of the ways I hold privilege or disadvantage in each category—with a little self-deprecating humor often helping here to facilitate student engagement.

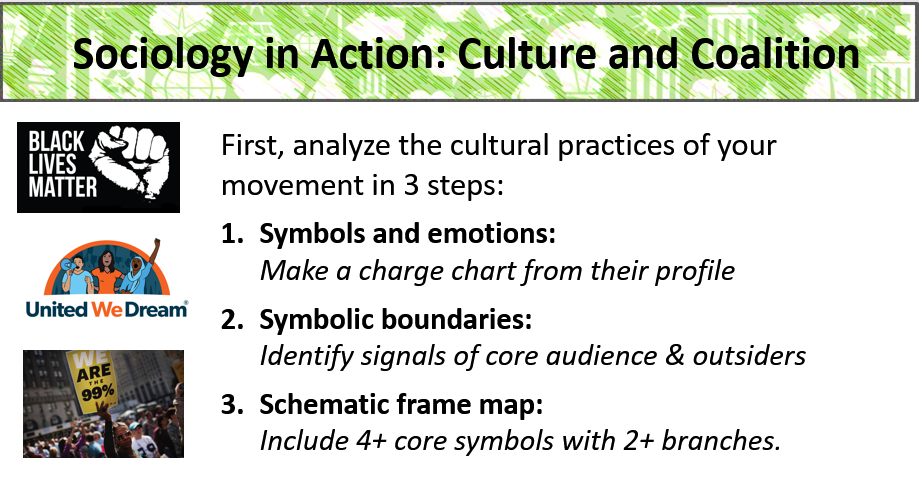

The activity continues with a quick review of intersectionality and schemas, leading to an introduction of the idea of mapping identities: showing how a complex identity can aggregate from roles, how roles build from beliefs and values, and how beliefs and values arise from symbols and experiences. We choose an example together—generally students call out a list of celebrities and vote on their favorite, which has ranged from Beyoncé to Donald Trump—and I place the celebrity’s name in a word bubble at the top of the board as they write their own name at the top of a graphic organizer (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Excerpt from the graphic organizer for Intersectional Identity Maps activity.

The process from there begins with a basic insight of intersectional studies—that identities build from roles corresponding to different lines of social categorization—and uses cultural sociology to investigate the schemas that give those roles meaning and the charged experiences that anchor those schemas. For each role we break down associated beliefs (e.g., about what Whiteness means to Donald Trump) and values (e.g., charge-carrying words like “nurturing” attached to the mother role). Finally, we pick a single belief and discuss charged memories (from past interaction rituals) that might anchor it; students complete their identity maps as they do the same. The students then break into pairs, walk each other through their maps, and offer peer review, leading to individual reflective writing on a prompt that challenges them to consider how their complex identity would play out in the context of public service.

Practical Scenarios

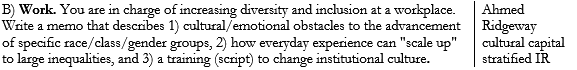

The final day of each week often puts students in a scenario that challenges them to use cultural analysis of intersectional difference to analyze and address social problems. One example is an exercise called Culture and Coalition, in which students work in teams to analyze the charged symbols, core audiences, and frames of a social movement to gain insight into the cultural dynamics of coalitions. Analyzing the collective identity and institutional culture of movements rather than abstract social categories—like race, gender, or class groups—enables students to push past stereotypes and explore shared schemas in specific historical contexts. Readings in prior weeks covered cultural activism (Ibrahim, 2017) and how movements seek resonance in social fields (Husu, 2013); this week’s readings are anchored by Hancock (2013) and how an intersectional lens can reveal new opportunities for previously separate movements to collaborate.

The activity starts with a simplified discourse analysis of three movement mission statements, modeling the work culturally competent professionals do in gleaning information about frames and values from textual data. I hand out the statements to students sitting in groups of three; we discuss the basic history and strategy of the movements, and each student chooses one of the three movements as their focus for the day. The discourse analysis begins with making a charge chart, a simple heuristic tool whereby students collect emotionally charged words and phrases in two columns corresponding to positive and negative valence. We pause to debrief, building a comprehensive charge chart for one movement together on the board.

With charged phrases identified, we launch into the work of mapping how symbols connect to perform the cultural work of inclusion, exclusion, and mobilization for each movement. From the charge chart on the board, I highlight two examples of a charged phrase involved in the construction of symbolic boundaries, one signaling the movement’s core audience and the other signaling outsiders. Students follow on this example to write about the signals of inclusion and exclusion in their own movement profile. They then complete their profile by identifying the four symbols most important to their movement’s collective identity and placing them in a schematic frame map—essentially a concept map showing the links between key components of a frame. To flesh out their frame map, they connect the four core symbols to additional symbols, emotions, and experiences that contribute to their meaning and resonance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sample slide from Culture and Coalition activity.

The activity closes with an analysis of how cultural difference relates to the challenges and opportunities of coalition. After a brief discussion of lessons learned from the study of past movements, students produce an intersectional strategy to intervene in inequality based on their research throughout the term. At each step, we examine the unique characteristics of race and use multiple cross-cutting categories to understand racial formation as a unique example of general processes of the formation of social and symbolic boundaries.

Exams as Synthetic Essays

Because the course balances practical training in cultural competency against sociological content knowledge, I use exams as an opportunity for students to pause and synthesize their knowledge of core concepts and authors at key points in the semester. The exams, however, use no multiple-choice or short-answer questions; they are synthetic essays that continue the course emphasis on using intersectional analysis and cultural knowledge to decode practical scenarios. The midterm questions draw from a list of roughly 30 key terms and 10 readings; students see a list of three on the day of the exam and assess how the terms can be useful to their ongoing Research to Action projects.

The final exam is take-home, delivered online, allowing students an opportunity to pull together complex concepts into coherent responses to practical challenges. The students receive five essay prompts, each with three sections challenging them to analyze a specific setting of their choice, place it in broader social context, and design an intervention that changes culture. Each question comprises a mix of four key concepts and authors to be referenced in the response (see example in Figure 4), and the concepts include an encouragement to repurpose, expand, or disagree with them. We make generic outlines for several questions together in class, ensuring that each student has the resources to engage the concepts and generate their own unique approach. When students take the exam, they see three randomly chosen questions and choose two to complete.

Figure 4. Sample synthetic essay prompt. Students enrich their answers with a detailed analysis of a specific workplace they choose, using the keyphrases at right.

Throughout the course, assessment aims to emphasize the development of practical tools; accountability comes primarily from peers and from the audience of professionals, community members, and peers who attend the Strategy Summit. All major assignments are tailored to student interest and go through multiple drafts and rounds of review from peers and community members, making plagiarism a non-issue and improving the final product. A consistent stream of small graded assignments helps to quickly identify when students might be going off track, but even more helpful has been the work students do to support and encourage the members of their teams.

Conclusion

This field report collects tools from one pilot project to support faculty and programs that seek to equip their students with an intersectional cultural competency adequate to the dynamic and complex diversity of the modern world. The redesign of the Cultural Emotions course has proven promising in evaluations, in high rates of successful course completion, and, most of all, in the quality of student work (all capstone projects are available online at praxicalsoc.org). This particular redesign is easily adaptable to any course in the social sciences relevant to cultural analysis, but the general approach of using action research and practical intervention to enrich course content has a substantially broader application. The Civic and Social Innovation Group at Cal State LA has already adapted a similar approach in political science, sociology, and education courses, and the group stands ready to support anyone interested in similar movements. For courses in the social sciences and humanities, this is not an add-on but a pivot, a way to simultaneously deepen content learning, help students build pathways to meaningful careers, and work alongside local communities to address pressing needs.

Still, some challenges remain. The most common complaint from students has been that the mix of theory, history, method, and practical intervention is a lot to process in one semester. Future paths of development may include a follow-on course allowing students to develop their proposals for implementation in partnership with local organizations, or certificate programs that support a deeper engagement with cultural competency in social change. As we build out these new supports, CaSIG is working to connect student teams with mentors who can help bring ideas from the Strategy Summit into their communities.

This course redesign aimed explicitly to engage and empower students who often find themselves marginalized and disempowered in traditional classrooms. Though its tools were created to serve a diverse student body of predominantly first-generation college students, faculty and programs serving privileged populations may want to consider adopting or adapting these tools for intersectional cultural competency, for two reasons: (1) They help privileged students decenter their own perspectives, understanding culture through careful listening in the context of action research; (2) these strategies may help to even the playing field for the marginalized students who do enter privileged spaces. When cultural competency assumes to teach the beliefs and values of marginalized groups by rote, it carries the danger of dehumanization, oversimplification, and stereotype (Sears, 2012). The vision of intersectional cultural competency presented here helps students invite themselves, their peers, and ultimately the communities they may serve to the same process of cultural analysis.

Because intersectional cultural competency asks students to shift their perspectives and adopt new ways of thinking and feeling, it is best considered as a long-term growth process offering students multiple opportunities to gain skills and knowledge, test them in the real world, reflect critically, and refine their approaches (Waldner, Roberts, Widener, & Sullivan, 2011). Students will emerge not just as culturally competent professionals but as creators of meaningful change when programs incorporate these tools across multiple courses within programs (Lopez-Littleton & Blessett, 2015) and throughout the university (Levin & Greenwood, 2001). Because new curriculum initiatives so often fail to navigate cultural differences inside and outside the academy, the methods of careful, humble cultural learning explored here are vital for curriculum reform movements as well. By challenging ourselves as faculty and practitioners to foster intersectional cultural competence and build coalitions that bridge historical divides—within and across disciplines, methodological approaches, universities, and communities—we model the forms of leadership and advocacy we hope to see from the students we serve.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Amodio, D. M. (2014). The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(10), 670-682. doi:.10.1038/nrn3800

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands / la frontera: The new mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Armstrong, E. A., & Bernstein, M. (2008). Culture, power, and institutions: A multi-institutional politics approach to social movements. Sociological Theory, 26(1), 74-99. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00319.x

Atkinson, M. P., & Hunt, A. N. (2008). Inquiry-guided learning in sociology. Teaching Sociology, 36(1), 1-7. doi:10.1177/0092055X0803600101

Bird, A., Mendenhall, M., Stevens, M. J., & Oddou, G. (2010). Defining the content domain of intercultural competence for global leaders. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(8), 810-828. doi:10.1108/02683941011089107

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carrizales, T. (2010). Exploring cultural competency within the public affairs curriculum. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 16(4), 593-606.

Carrizales, T., Zahradnik, A., & Silverio, M. (2016). Organizational advocacy of cultural competency initiatives: Lessons for public administration. Public Administration Quarterly, 40(1), 126-155.

Chao, M. M., Okazaki, S., & Hong, Y. (2011). The quest for multicultural competence: Challenges and lessons learned from clinical and organizational research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(5), 263-274. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00350.x

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785-810. doi:10.1086/669608

Choo, H. Y., & Ferree, M. M. (2010). Practicing intersectionality in sociological research: A critical analysis of inclusions, interactions, and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociological Theory, 28(2), 129-149.

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1-20. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Collins, R. (2014). Interaction ritual chains and collective effervescence. In C. Scheve & M. Salmella (Eds.), Collective emotions: Perspectives from psychology, philosophy, and sociology (pp. 299-311). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Contreras, F., & Contreras, G. J. (2015). Raising the bar for Hispanic serving institutions: An analysis of college completion and success rates. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 14(2), 151-170. doi:.org/10.1177/1538192715572892

Fals Borda, O. (2013). Action research in the convergence of disciplines. International Journal of Action Research, 9(2), 155-167.

Ferree, M. M. (2003). Resonance and Radicalism: Feminist framing in the abortion debates of the United States and Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 109(2), 304-344. doi:10.1086/378343

Fisher-Borne, M., Cain, J. M., & Martin, S. L. (2015). From mastery to accountability: Cultural humility as an alternative to cultural competence. Social Work Education, 34(2), 165-181. doi:.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.977244

Flaherty, C. (2014, February 27). Cal State LA faculty split on changing diversity requirement. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/02/27/cal-state-la-faculty-split-changing-diversity-requirement

Gamson, W. A. (2009). My life-long involvement with games. Sociological Forum, 24(2), 437-447. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01108.x

Garran, A. M., & Rozas, L. W. (2013). Cultural competence revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22(2), 97-111. doi:10.1080/15313204.2013.785337

Gibbs, P., Cartney, P., Wilkinson, K., Parkinson, J., Cunningham, S., James-Reynolds, C., … Pitt, A. (2017). Literature review on the use of action research in higher education. Educational Action Research, 25(1), 3-22.

Goodwin, J., Jasper, J. M., & Polletta, F. (2009). Passionate politics: Emotions and social movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hancock, A.-M. (2007). When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on Politics, 5(1), 63-79. doi:10.1017/S1537592707070065

Hancock, A.-M. (2013). Solidarity politics for millennials: A guide to ending the oppression Olympics (2011 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hogg, M. A. (2016). Social identity theory. In S. McKeown, R. Haji, & N. Ferguson (Eds.), Understanding peace and conflict through social identity theory (pp. 3-17). Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29869-6_1

Hollinsworth, D. (2013). Forget cultural competence; ask for an autobiography. Social Work Education, 32(8), 1048-1060. doi:10.1080/02615479.2012.730513

Husu, H.-M. (2013). Bourdieu and social movements: Considering identity movements in terms of field, capital and habitus. Social Movement Studies, 12(3), 264-279. doi:10.1080/14742837.2012.704174

Ibrahim, A. (2017). Arab Spring, Favelas, borders, and the artistic transnational migration: Toward a curriculum for a global hip-hop nation. Curriculum Inquiry, 47(1), 103-111. doi:10.1080/03626784.2016.1254498

Irazabal, C., & C. Harris, S. C. (2011). Transforming subjectivities: Service that expands learning in urban planning. In T. Angotti, C. Doble, & P. Horrigan (Eds.), Service-learning in design and planning: Educating at the boundaries (pp. 107-124). Oakland, CA: New Village Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt21pxmfs.12

Jasper, J. M. (2017). The doors that culture opened: Parallels between social movement studies and social psychology. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 20(3), 285-302. doi:10.1177/1368430216686405

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., & Napier, J. L. (2009). Political ideology: Its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 307-337. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600

Jost, J. T., Nam, H. H., Amodio, D. M., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2014). Political neuroscience: The beginning of a beautiful friendship. Political Psychology, 35, 3-42. doi:10.1111/pops.12162

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lamont, M. (2012). Toward a comparative sociology of valuation and evaluation. Annual Review of Sociology, 38(1), 201-221. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120022

Levin, M., & Greenwood, D. (2001). Pragmatic action research and the struggle to transform universities into learning communities. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp. 103-113). London: Sage.

Levin, M., & Greenwood, D. J. (2016). Creating a new public university and reviving democracy: Action research in higher education. New York: Berghahn Books.

Lopez-Littleton, V., & Blessett, B. (2015). A framework for integrating cultural competency into the curriculum of public administration programs. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 21(4), 557-574.

Mattsson, T. (2014). Intersectionality as a useful tool: Anti-oppressive social work and critical reflection. Affilia, 29(1), 8-17. doi:10.1177/0886109913510659

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30(3), 1771-1800.

McNiff, J. (2013). Action research: Principles and practice. New York: Routledge.

Montoya, M. E. (1994). Mascaras, Trenzas, y Grenas: Un/masking the self while un/braiding Latina Stories and legal discourse. Chicano-Latino Law Review, 15, 1-37.

Norman-Major, K. A., & Gooden, S. T. (2012). Cultural competency for public administrators. New York: Routledge.

Saldivar, K. M. (2015). Team-based learning: A model for democratic and culturally competent 21st century public administrators. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 21(2), 143-164.

Sears, K. P. (2012). Improving cultural competence education: The utility of an intersectional framework. Medical Education, 46(6), 545-551. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04199.x

Sewell, W. H. (2005). Logics of history: Social theory and social transformation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sharp, G., & Lee, B. A. (2017). New faces in rural places: Patterns and sources of nonmetropolitan ethnoracial diversity since 1990. Rural Sociology, 82(3), 411-443. doi:10.1111/ruso.12141

Strickland, D., & Strickland, C. (2013). My sociology: The challenge of transforming classroom culture from a focus on grades to a focus on learning. Journal of Public and Professional Sociology, 5(2). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jpps/vol5/iss2/4

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Waldner, L., Roberts, K., Widener, M., & Sullivan, B. (2011). Serving up justice: Fusing service learning and social equity in the public administration classroom. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 17(2), 209-232.

Williamson, M. (2017). Solving social problems: Service learning in a core curriculum course. Journal of Public and Professional Sociology, 9(1). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jpps/vol9/iss1/1

Wynn, J. R. (2009). Digital sociology: Emergent technologies in the field and the classroom. Sociological Forum, 24(2), 448-456. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01109.x

Zuberi, T., & Bonilla-Silva, E. (2008). . White logic, White methods: Racism and methodology. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Author Biography

Dmitri Seals is a cultural sociologist of inequality, completing a PhD in Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Lecturer in Sociology and founding member of the Civic and Social Innovation group at California State University, Los Angeles. He researches intersections of symbolic, political, and material inequality using methodological tools from participatory action research to computational social science. His current work examines political disengagement and polarization, intersectionality in symbolic boundary work online, and the impact of cultural difference on inequalities of income and wealth.