By Elizabeth L. Sweet | Cultural humility can help planning faculty, students, and practitioners commit to ongoing self-reflection and critique of their social, cultural, racial, gendered, and other identities in an effort to identify how they are implicated in inequity, especially in relation to working in communities of color. While cultural competence has become an increasingly popular way to encourage more equitable relationships between professionals and communities, the author suggests that the colonial underpinnings of its logic make it not only less desirable than cultural humility but also a potential facilitator of inequity in planning work. Drawing from her experience as a planning theorist and faculty member, the author shows how the philosophical origins of Western colonial thinking have influenced planning. She also outlines concrete ways journal editors can relinquish their status as experts and gatekeepers of accepted knowledge, thereby decolonizing planning theory and the canon more generally. Finally, by describing two reflection activities—“What?/So What?/Now What?” and “Locating Oneself”—the author provides tools that planning educators can use to guide and reinforce reflection on students’ social, cultural, gendered, and racial identities, and to highlight injustices committed by planners. By injecting cultural humility, as opposed to cultural competency, into planning theory literature, and education, planning practice could be transformed, preventing the often-destructive history of planning practices in communities of color from being repeated.

Author Note

Elizabeth L. Sweet, Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Elizabeth L. Sweet, Assistant Professor of Instruction, Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, 325A Gladfelter Hall, 1115 Polett Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19122. Phone: (215) 204-2960. E-mail: bsweet@temple.edu

Graduate planning programs tend to emphasize professionalism, knowledge acquisition, and proficiency development in specific areas within the discipline, such as housing, economic development, or transportation. Graduates are then expected to use the expertise gained from their training to make cities, towns, and communities better in some way. Professional status and validity depend on expert status, and power is contingent on a planner’s perceived superior knowledge in relation to the communities in which they work. However, from this place of superior knowledge—and because expertise naturally leads one to prioritize one’s own perspective—it may be difficult for a planner to understand, value, or cultivate the diverse knowledge, history, or experiences of community members. Indeed, doing so may diminish a planner’s perceived power and status as a professional.

Graduate planning programs tend to emphasize professionalism, knowledge acquisition, and proficiency development in specific areas within the discipline, such as housing, economic development, or transportation. Graduates are then expected to use the expertise gained from their training to make cities, towns, and communities better in some way. Professional status and validity depend on expert status, and power is contingent on a planner’s perceived superior knowledge in relation to the communities in which they work. However, from this place of superior knowledge—and because expertise naturally leads one to prioritize one’s own perspective—it may be difficult for a planner to understand, value, or cultivate the diverse knowledge, history, or experiences of community members. Indeed, doing so may diminish a planner’s perceived power and status as a professional.

Several components of planning curriculum and theory, including advocacy planning (Clavel, 1994; Davidoff & Gold, 1970; Peattie, 1968), the reflective (deliberative) practitioner (Forester, 1999; Schön, 1987, 2017), equity planning (Krumholz, 1982, 2011), and collaborative planning (Healey, 1997; Innes & Booher, 1999), have helped to deemphasize the exclusivity of the power and knowledge of professional planners in practice. Nevertheless, these approaches do not urge planners to engage in self-reflection beyond their performance as planners. More specifically, they do not promote an analysis and critique of the planner’s own social, cultural, racial, or gendered position and power in society.

One attempt at encouraging professionals to identify and account for social, cultural, racial, and gendered differences has been through cultural competency training. Practitioners learn about other cultures in order to engage with or provide services to communities in a respectful manner. By virtue of practitioners’ presumed learning about different or “Other” cultures, they will be better prepared to help facilitate more effective interactions and understand difference (Betancourt, Green, Carrillo, & Owusu Ananeh-Firempong, 2003).

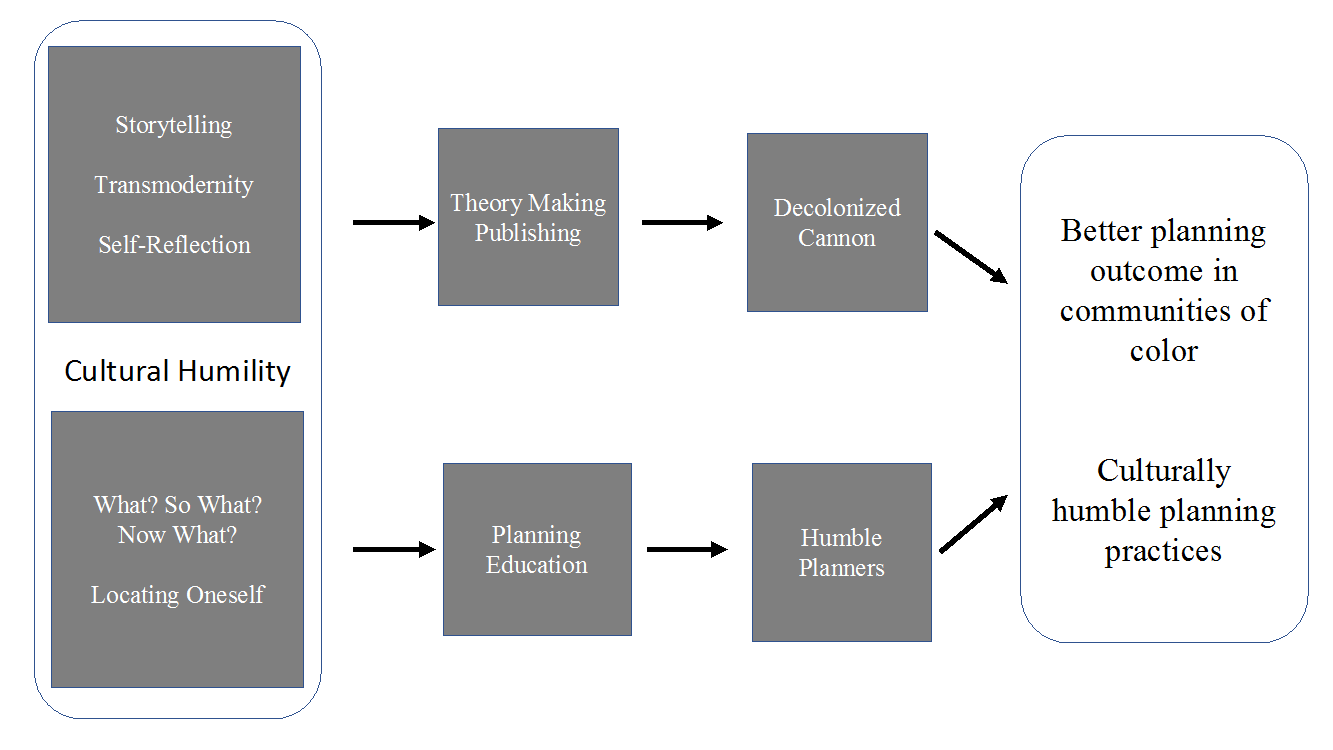

In this article, I question the underpinning logic of cultural competency in the context of planning and suggest that cultural humility represents a more productive approach to engaging with communities, especially communities of color. Specifically, I suggest that if planning educators and the gatekeepers of planning publications—and therefore of the planning canon—embraced cultural humility, a decolonial process could occur within the planning discipline (see Figure 1). Cultural humility can illuminate the prevailing power position of experts in the field and their boarder positionality vis-a-vi the communities with which they work. The planning profession, with its long history of racial, cultural, and gendered discrimination (see Squire, 2018 on racialized housing policy; Ross & Leigh, 2000 on structural racism in planning), has an opportunity to transform itself by embracing cultural humility in theory, education, and practice.

Figure 1. Logic model for cultural humility in planning education and theory.

Developed by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia (1998), the concept of cultural humility contests the belief that one can actually become competent in another culture; rather, it is a practice of and ongoing commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique by professionals for the purpose of rebalancing power inequities. The goal of cultural humility is for practitioners to develop “nonpaternalistic” collaborations with communities (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998, p. 117) and to “relinquish” their position as expert (Ross, 2010, p. 318). Institutional accountability through cultural humility is also an important component of system change (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia 1998). In order for planning departments in universities and city halls as well as publishing institutions to embrace cultural humility, they too, must engage in self-reflection and self-critique, asking questions such as, Who is getting published, hired, retained, and tenured, and who is not? Who is getting grants and awards, and is generally seen as knowers in the field, and who is not? Do the answers to these questions represent the diversity that cultural humility demands? While cultural humility was originally developed with medical practitioners and social workers in mind, the concept might shift the dynamics of planners’ interactions with the public in such a way as to support and embrace diversity rather than simply manage it through a demonstrated competence or knowledge about the Other. This latter outcome represents the overarching goal of cultural competency (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Central to my argument is an interrogation of the prevailing nature of planners as “experts” and the identification of ways to decenter expertise in order to facilitate more equitable planning theory, education, and practice (Ross, 2010). In a letter to the editor in the Journal of Planning Education and Research, Alexander (2011) claimed that my co-authored article about insurgent planning in Russia (Sweet and Charkars, 2010) was really not about planning at all and that every time we used the word planning it could have been switched to activism, and the meaning of the article would not have changed. He was concerned that the definition of planning was being watered down and that it should be considered in more specific terms. I interpreted his letter as a call to leave planning to the professionals since insurgent planning by nature is practiced by non-professional planners. I responded to his letter (Sweet, 2011), arguing that insurgent planning and other similar types of planning challenge the boundaries established in previous iterations of planning theory (primarily by White men). I also maintained that planners must reassess and rethink the canon—replete with racism, sexism, and power dynamics—which has historically wreaked havoc on many communities of color (Kerns, 2002; Ross & Leigh, 2000; Shepard, 2015) and limited opportunities for women’s health, safety, and economic attainment (Sweet and Ortiz Escalante, 2010; Spain, 2014). Alexander (2016), in a footnote, acknowledged that my argument was valid (p.101). The point of recounting this relatively recent exchange is to highlight the difficulty of challenging the narrow conception of planning as being practiced exclusively by trained professionals. It also speaks more broadly to the need for self-reflection, soul searching, and repentance within the discipline. I propose cultural humility as a process and vehicle for addressing this need, and as an antidote to the historical and current racial, gendered, and other inequities imbedded in planning theory, teaching, and practice.

To set the context for my argument, I begin with a detailed discussion of cultural competence and its colonial legacy via vestiges of Eurocentric philosophy. I then describe cultural humility and how it could guide or frame planning theory, be taught in planning schools, and subsequently be practiced by professional planners. I use several examples of my own experiences as a planning faculty member, practitioner, and theorist to support these ideas and suggest concrete ways for planners to become less “expert” and more humble.

Recognizing the Colonial in Competence

In many professions, competencies are seen as the gold standards for the acquisition of knowledge and skills. If students can demonstrate that they have acquired sufficient knowledge and skills, they are recognized officially as professionals. Cultural competence embodies “knowledge about diverse people and their needs, attitudes that recognize and value difference, and flexible skills to provide appropriate and sensitive care to diverse populations” (Kools et al., 2014, p. 52). It signifies competence in “particular skill or ability implying its completion” (Kools, Chimwaza, & Macha, 2014, p. 52). Cultural competence views cultural differences as a kind of knowledge that can be learned, and its proponents hold that once practitioners (and the institutions they work in) become culturally competent, they will be able to direct action and engage with people from different cultures in a way that is efficient, respectful, and effective.

Using the word competence implies that culture can be learned and, by extension, is finite and static—like the process of learning how to do a linear regression. Some of the literature on cultural competence counteracts this interpretation by suggesting that cultural competence is also a commitment to “building on dynamic experiences over time” (Kools et al., 2014, p. 52); some have even argued that cultural humility is a subset of cultural competence (Betancourt et al., 2003). Language is important here because it puts competence in the hands of professionals and their institutions. Said another way, it positions the Other as knowable and the professional as the knower, reflecting the colonial histories of Latin America, Asia, and Africa. To illustrate this point, it is worth reviewing the observations of some Latin American theorists on decolonializing thinking[1] as it relates to universalism, modernity, and truth.

The idea of culture is enveloped by a rhizomic structure of Eurocentric philosophy that is dominated by several phenomena, namely universalism, modernity, and truth. Universalism emerged from Descartes’ declaration of “I think therefore I am,” or the “God-eyed view” of knowledge (Grosfoguel, 2011, p. 5), extensively deliberated in the minds of the mostly White male philosophers in Europe. Castro-Gomez (2003) referred to this way of seeing and understanding as “point zero,” the perspective that obscures its viewpoint; it “represents itself as being without a point of view” (Grosfoguel, 2011, p. 5), that is, objectivity. Often, when I ask students in my undergraduate classes to read traditional mainstream perspectives about economics or the environment and then ask them to read alternative perspectives, many of them suggest that the alternatives are biased. They fail to see the bias within mainstream ideas since those ideas are presented from point zero, which students have been socialized to accept and recognize as balanced and unbiased. Eurocentric universalism, the Gods-eye view, or point zero perspectives are understood in Western thought as a-spatial, a-temporal, and a-relational, and therefore objective. The majority of students in my classes associate objectivity with mainstream point-zero content. Within this dominant view, all Other cultures and their worldviews and values are seen as subjective/biased and, I would argue, inferior, especially in the context of modernity. For example, I ask students to read Ranney’s (2002) chapters on economic restructuring in which he recounts stories about his work as a mechanic in Solo Cup and other Chicago factories to explain how workers of color and women have experienced economic change. After reading Ranney’s chapters, however, students frequently suggest that he is biased because he is writing about his own experience and observations in the factory. Conversely, when they read Arndt’s (1989) chapter on economic development history, which focuses exclusively on European ideas, students rarely identify any bias in Arndt’s writing.

While objectivity denies the subjectivity of difference, modernity is overvalued regarding cultural diversity. Since the 1960s, Dussel has struggled to decenter European thinking, specifically in relation to modernity. He argued that non-Western people have been “blinded by the dazzling ‘brightness’—in many cases only apparent—of Western culture and modernity” (Dussel & Fornazzari, 2002, p. 221). Similarly, Fanon (1963) reminded us that not only are non-Western cultures obscured by the dazzle of the West, but modern Western interventions on colonial or former colonial subjects were ineffective and at times even disastrous. The notion that Western interventions are necessary to modernize the Other reeks of superiority and disdain, in a kind of false or, at best, misguided benevolence. Concepts like the “smart city” or “new urbanism” are mired in overdetermined modernity or newness that perpetuates inequality via the growing digital divide (Wiig, 2016) or high-priced entry (Harrison 2010). Dussel’s (2011, 2012) concept of transmodernity emphasizes a process whereby traditional and premodern ways of living and thinking are coupled with modern and postmodern systems rather than being replaced by them. More specifically, traditional, indigenous, and Other cultures and ways of knowing are valued and combined with, rather than superseded by, modernity. Transmodernism is humble. It recognizes the best in many traditions and offers an opportunity to embrace the value and usefulness of many approaches to urban planning theory.

According to the dualistic Western thinking that dominates planning practice, if the planner is competent, then the subjects of the planning are not competent, requiring the expert to fix them and their communities. The power dynamics such a competent/incompetent framework are socially constructed but have real-world consequences for the subjects of planning. A risk of cultural competence in planning is the preservation of the status quo and a lack of acknowledgement of the impacts of Western cultural imperialism. Indeed, cultural competence resembles colonial experiences in communities, especially communities of color and other marginalized communities. As Grosfoguel (2007) suggested, maintaining a colonial (i.e., Western) approach constrains and limits the “radicality” (p. 212) of questions or critiquing Eurocentric epistemologies, such as, Who is a knower and who is known? Moving away from planners as knowers and communities as known, opens an opportunity for transformation, for relationships between planners and communities to be more equal.

A Decolonial Turn in Planning Theory with Cultural Humility

Cultural humility is a way to practice transmodernism. It enables professional planners to uncover, through self-reflection, the overreliance and unjustifiable value placed on Euro/U.S. knowledge, perspectives, and beliefs, and provides a process for planners to assess how their positions of power and privilege have impacted planning practice. Within this framework, professionals acknowledge that, while they cannot gain competence in another culture, they are obligated to examine their own culture and professional position in an effort to disclose their biases, limited vision, and privilege, and to understand “the ways their culture influences their personal attitudes, values and beliefs” (Hook et. al. 2013, p. 353). Self-reflection lays the groundwork for cultural humility and strengthens the potential for “radicality”—opening opportunities to create equal partnerships and decenter the power of the expert.

As my earlier story about the letter writer demonstrates, the halls of planning theory have been tightly managed and monitored. As Grosfoguel (2012) pointed out, not only is Descartes’ philosophical motto “I think therefore I am” (with its a-spatial, a-temporal, and a-relational origins) a foundation of Western thought, but it is also a justification for the expert, for superior thinking, and power positions. Had the letter writer been one of the journal’s peer reviewers, our article may not have seen the light of day since it was not bound by the point-zero, objective, professional planning model. Indeed, in other of my experiences, editors have used their professional power as experts to oppose work about women and communities of color that does not follow colonial logic but employs storytelling instead. These experts have used their gatekeeping powers to exclude non-Western cultural ideas and theories from the planning canon.

In one instance, I submitted an article about Latina Kitchen Table Planning Saving Communities: Intersectionality and Insurgencies in an Anti-Immigrant City (Sweet, 2015) to one of the top planning journals. The article offered a cultural humility argument, without using that particular phrase, related to professional planners working in Latino/a immigrant communities. It was both theoretical and methodological, and also used storytelling to represent the realities within the community. The peer reviewers recommended the article for publication, but the editor rejected it. The editor wrote, “You just have to be more analytical and focused about it. Lecturing and hectoring don’t replace rational argument.” What the editor referred to as “lecturing” was in fact storytelling, which is not always linear or rational. Storytelling often traverses time and space and can delve deeply into relationships and how they shape and mold realities. Stories are often filled with twists and turns that, from a God’s-eye view, could be interpreted as unfocused but nonetheless represent experiences in everyday life. Storytelling is itself an analytical framework (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). In the case of my submitted article, storytelling about women of color and how professional planners could engage at a kitchen table with them was rejected as an inappropriate and unfocused mode of analysis. The editor’s call for “rational argument” precisely exposes colonial thinking separating bodies, minds, space, and time. It embraces European/U.S. reason (“I think, therefore I am”) and rejects Others’ emotions and experiences as valueless. Planning theory needs to embark on a decolonial turn by fundamentally rethinking reason as a benchmark since time, place, and relationships are not always governed by reason but do constitute life outside of the point-zero perspective.

Cultural humility is a concrete and widely documented approach to acknowledging and contesting colonial thinking and practice within the academy (Cordova, 1998). If incorporated into planning theory and education, it will positively impact practice. What if the editor had suggested a conference call with the reviewers? What if the editor, before writing the long justification for rejecting my article, reflected on their power and privilege relative to the author and the community with whom the author was working? What if the editor analyzed how their own culture and background influenced their attitude, values, and beliefs? While I am not naïve about the amount of work editors do, one cannot ignore that they are the main arbiters of planning theory; thus, by embracing cultural humility, they would do much decolonialize planning theory.

Locating Cultural Humility in Planning Education

Planning education is central to cultural humility as well. In this section, I suggest two classroom activities that would encourage both self-reflection and reflection on the field of planning. The first is the “What?/So What?/Now What?” reflection tool described by the Northwest Service Academy (https://www.servicelearning.msstate.edu/files/nwtoolkit.pdf); the second is the “Locating Oneself” process developed by the NoVo Foundation (https://www.movetoendviolence.org/resources/racial-equity-liberation-week-1-locating-oneself/). These activities not only comprise a process for students to incorporate as they enter the profession but also help them to reflect on the history and theory of planning. Students are able to recognize the inequities and the often dysfunctional ways in which planning has occurred, and intentionally move toward a decolonized model with cultural humility as a basis for action.

Ross (2010) used the “What?/So What?/Now What?” tool as a way for students to reflect on their community engagement while conducting community-based activities. Throughout the semester, students were asked to write three reflection papers using this model and to assess their role and that of their student colleagues in the project. First, they asked themselves “what” questions: What happened? What did I observe? What issues are being attended to or groups are being served? What were the outcomes of the project and for whom? What events or significant incidents occurred? What was of particular notice? How did I feel during the process? (Watson, 2001, p. 4). They were then asked “so what” questions: What was the meaning and significance of the activity for me? How did I feel about the service activity? What ideas were generated by the service activity for me? What is my analysis of the service experience? (Stuart, 2001, p. 4). Finally, in the “Now what?” phase, students were asked to think about what comes next: How will I think or act in the future as a result of this experience? What are the broader implications of the service experience? How can I apply learning from this experience in future activities? (Stuart, 2001, p. 4). This process has the potential to help students in studio or service-learning classes to “tune in” to who they are and what impact their work has on communities. Ross (2010) concluded that while this approach to teaching cultural humility is promising, an intentional and ongoing conversation about privilege is needed to reinforce the goal of cultural humility practice.

The NoVo Foundation’s Move to End Violence program has developed “Locating Oneself,” a process of intentional and intersectional exploration of privilege and position that responds well to Ross’s (2010) recommendation. In a virtual learning presentation, Monica Dennis and Rachael Ibrahim lead participants through the process of “Locating Oneself” (https://www.movetoendviolence.org/resources/racial-equity-liberation-week-1-locating-oneself/), which they describe as an internal and external practice of self-reflection, a way to repair, and a liberatory practice challenging systems of oppression that strip individuals of their power. They suggest a five-step process in which participants do the following:

- Get grounded or re-grounded via a short breathing activity.

- Practice acknowledgements related to place and people (e.g., Who are the previous inhabitants of this land? Who are the people who have made our work and life possible?)

- Set up community agreements including, for example: be active listeners, be present; silence the internal chatter; push through our growing edge; recognize that there are no quick fixes; trust the process; talk in terms of “racism and” (to make sure racism is not watered down in a sea of diversity); recognize the intersection of identities; focus on the impact of us—acknowledge the impacts we have had on Others, no matter our intentions.

- Set up a framework for discussion that describes our current state and our goals, moving from systems of oppression to liberatory practices. Systems of oppression include but are not limited to four phenomena: (a) they disconnect us from our source (divine, people, creations, purpose, land bases)—so, we need to reconnect; (b) they disassociate us from our bodies (control of having or not babies, value work from our bodies or not, labor paid for or not)—so, we need to reclaim our bodies; (c) they distance us from our emotions (emotions are not acknowledged as a way of knowing, we are discouraged from talking about what we feel)—so, we need to re-engage with our feelings; (d) they distort our stories (stories are created that do not center or represent peoples’ actual realities)—so, we need to restore our stories. Understanding how systems of oppression impact us is key to unyoking ourselves from them.

- Locate ourselves by answering these questions: What do I know about myself and my people? Who are my people? What are the impacts my people and I are having and experiencing? How do my identities intersect with racism? When, where, and how do I enter conversations? How are my stories connected to the stories of others? It is important to understand and acknowledge our histories because history shapes experiences, history shapes relationships, and history structures approaches to everyday practice and professional practice.

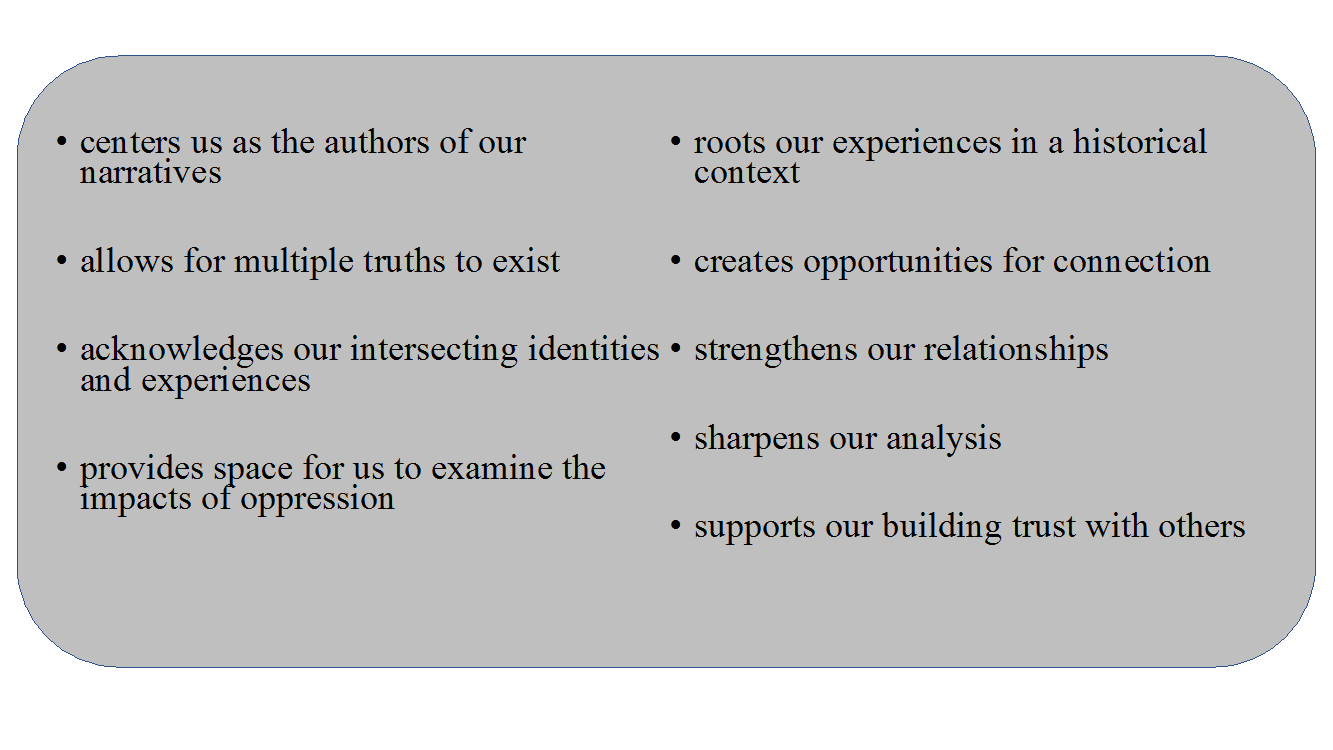

Locating oneself is where liberatory practice occurs (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impacts of “Locating Oneself.”

In the “Locating Oneself” process, an individual sometimes needs to grieve some aspects of their identities and histories, which is not about guilt but acknowledging how their histories and people might have negatively impacted others or been negatively impacted by others. By locating themselves and understanding what that location means—that is, their positionality[2]—they are better equipped to practice cultural humility. They have a better sense of who they are at that moment and are able to engage in an ongoing analysis as they change and understand more about themselves and their relations to others, in different places, times, and circumstances. Through this practice, a person rejects “I think, therefore I am” and acknowledges that their existence and experiences are the results of history, time, space, and relationships. By locating themselves, they engage in a decolonial practice that would serve planning theorists, students, faculty, and practitioners as a check on privilege, diminish expert positions, and ground them in cultural humility.

Since cultural competence is linked to colonial thinking and Western dominance, specifically in placing practitioners in the position of knower and Others in the position of known, cultural humility is a better approach. As the logic model (Figure 1) conveys, if editors and other gatekeepers of the planning canon embrace cultural humility, they will help to reduce the philosophical grip that Euro/U.S. colonial beliefs and values have on the field. If planning curricula incorporate activities such as “What?/So What?/Now What?” and “Locating Oneself” to train planners how to engage in ongoing self-reflection and self-critique not only of their work, but of who they are—their social, cultural, and racial identities—there is a chance that the often destructive history of planning in communities of color will not be repeated.

References

Alexander, E. R. (2011). Letter to the Editors: Insurgent Planning in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(2), 220.

Alexander, E. R. (2016). There is no planning—only planning practices: Notes for spatial planning theories, Planning Theory, 15(1), 91-103.

Arndt, H. W. (1989). Economic development: The history of an idea. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., & Owusu Ananeh-Firempong, I. I. (2016). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports, 118(4), 293-302.

Castro-Gómez, S. (2004). La Hybris del Punto Cero: Biopolíticas imperiales y colonialidad del poder en la Nueva Granada (1750-1816) [Hybris of point zero: Imperial and colonial biopolitics of the power of New Granada (1750-1816)]. Tabula Rasa, 4, 339-346.

Clavel, P. (1994). The evolution of advocacy planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(2), 146-149.

Córdova, T. (1998). Power and knowledge: Colonialism in the academy. In C. Trujillo (Ed.), Living Chicana theory (pp. 17-45). Berkeley, CA: Third Woman Press.

Davidoff, L., & Gold, N. N. (1970). Suburban action: Advocate planning for an open society. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 36(1), 12-21.

Dussel, E. (2011). From critical theory to the philosophy of liberation: Some themes for dialogue. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(2), 16-43

Dussel, E. D. (2012). Transmodernity and interculturality: An interpretation from the perspective of philosophy of liberation. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(3), 28-59.

Dussel, E. D., & Fornazzari, A. (2002). World-system and” trans”-modernity. Nepantla: Views from South, 3(2), 221-244.

Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. New York: Grove.

Forester, J. (1999). The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn: Beyond political-economy paradigms. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 211-223.

Grosfoguel, R. (2011). Decolonizing post-colonial studies and paradigms of political-economy: Transmodernity, decolonial thinking, and global coloniality. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(1), 1-38

Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies. British Columbia: University of British Columbia Press.

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington E. L., Jr., & Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 353-366

Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (1999). Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: A framework for evaluating collaborative planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 65(4), 412-423.

Kerns, J. K. (2002). A social experiment in Greenbelt, Maryland: Class, gender, and public housing, 1935-1954 (Doctoral dissertation). University of Arizona.

Kools, S., Chimwaza, A., & Macha, S. (2015). Cultural humility and working with marginalized populations in developing countries. Global Health Promotion, 22(1), 52-59.

Krumholz, N. (1982). A retrospective view of equity planning: Cleveland 1969-1979. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(2), 163-174.

Krumholz, N. (2011). Making equity planning work: Leadership in the public sector. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Porter, L., Sandercock, L., Umemoto, K., Umemoto, K., Bates, L. K., Zapata, M. A., … & Sletto, B. (2012). What’s love got to do with it?: Illuminations on loving attachment in planning. Planning Theory and Practice, 13(4), 593-627.

Peattie, L. R. (1968). Reflections on advocacy planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 34(2), 80-88.

Ranney, D. (2002). Global decisions, local collisions: Urban life in the new world order. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Rose, G. (1997). Situating knowledges: Positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography, 21(3), 305-320.

Ross, C. L., & Leigh, N. G. (2000). Planning, urban revitalization, and the inner city: An exploration of structural racism. Journal of Planning Literature, 14(3), 367-380.

Ross, L. (2010). Notes from the field: Learning cultural humility through critical incidents and central challenges in community-based participatory research. Journal of Community Practice, 18(2-3), 315-335.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Higher Education Series.

Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Routledge.

Shepard, A. (2015). Hurricane Sandy and urban planning in New York City’s minority neighborhoods: An unanticipated outcome (Doctoral dissertation). Long Island University, The Brooklyn Center.

Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative inquiry, 8(1), 23-44.

Spain, D. (2016). Constructive feminism: Women’s spaces and women’s rights in the American city. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Squire, H. (2018). A brief-ish history of housing policy in the United States [Blog entry]. Retrieved from https://heathersquire.com/2018/04/24/a-brief-ish-history-of-housing-policy-in-the-united-states/

Sweet E. L. (2011). Response to letter to editors: Action and planning—Where do we draw the line? Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(2), 221-222.

Sweet, E. L. (2015). Latina kitchen table planning saving communities: Intersectionality and insurgencies in an anti-immigrant city. Local Environments: International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 20(6), 728-743.

Sweet, E. L., & Chakars, M. (2010) Identity, culture, land, and language: Stories of insurgent planning in the Republic of Buryatia in Russia. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 30(2), 198-209.

Sweet, E. L., & Ortiz Escalante, S. (2010). Planning responds to gender violence: Evidence from Spain, Mexico, and the Unites States. Urban Studies, 47(10), 2129-2147.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117-125.

Watson, S. (2001). Northwest Service Academy Reflection Toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.servicelearning.msstate.edu/files/nwtoolkit.pdf

Wiig, A. (2016). The empty rhetoric of the smart city: From digital inclusion to economic promotion in Philadelphia. Urban Geography, 37(4), 535-553.

Author Biography

As an expert in planning theory and qualit ative research methodologies, Dr. Elizabeth L. Sweet teaches at Temple University in the Department of Geography and Urban Studies. Dr. Sweet engages in collaborative community economic development with a focus on the links between economies, violence, and identities. Using feminist and anti-racist frameworks, her work in Latino communities in the U.S. and in Latin America has led to long term collaborations and inclusive projects that both push the boundaries of planning theory and methods while at the same time provides practical intervention practices for planners. In recent publications she has proposed the use of body map storytelling and community mapping as innovative ways to co-create data with communities on a wide range of issues and solutions to urban problems. Theoretically, these methods create awareness that enables planners and communities to re-envision the relationships between people and their environments and see the visceral, historical, and spiritual bonds. These new understandings promote new practices. Dr. Sweet has also been very active in promoting diversity and inclusion within university settings through organizing events, student recruitment, and publishing both research and teaching articles on the same. She is popular among students to whom she provides extensive mentorship and guidance.

ative research methodologies, Dr. Elizabeth L. Sweet teaches at Temple University in the Department of Geography and Urban Studies. Dr. Sweet engages in collaborative community economic development with a focus on the links between economies, violence, and identities. Using feminist and anti-racist frameworks, her work in Latino communities in the U.S. and in Latin America has led to long term collaborations and inclusive projects that both push the boundaries of planning theory and methods while at the same time provides practical intervention practices for planners. In recent publications she has proposed the use of body map storytelling and community mapping as innovative ways to co-create data with communities on a wide range of issues and solutions to urban problems. Theoretically, these methods create awareness that enables planners and communities to re-envision the relationships between people and their environments and see the visceral, historical, and spiritual bonds. These new understandings promote new practices. Dr. Sweet has also been very active in promoting diversity and inclusion within university settings through organizing events, student recruitment, and publishing both research and teaching articles on the same. She is popular among students to whom she provides extensive mentorship and guidance.

-

-

See also Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; Hall, S., Held, D., & McGrew, A. G. (Eds.). (1992). Modernity and its futures. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ↑

-

-

Feminist geographers, among others, have argued that knowledge is a product of the biases, privileges, and power of its creator, and that these positions constitute their positionality and make all knowledge partial knowledge. For a review of positionality as it relates to knowledge creation see Rose (2007). ↑