Author Note

Tami L. Moore, Higher Education and Student Affairs Program, Oklahoma State University–Tulsa; Michael D. Stout, Human Development and Family Science, Oklahoma State University–Tulsa; Patrick D. Grayshaw, Human Development and Family Science, Oklahoma State University–Tulsa; Autumn Brown, Social Foundations of Education, Oklahoma State University–Main Campus; Nadia Hall, Higher Education and Student Affairs Program, Oklahoma State University–Main Campus; C. Daniel Clark, Higher Education and Student Affairs Program, Oklahoma State University–Main Campus; Jonathan Marpaung, Higher Education and Student Affairs Program, Oklahoma State University–Main Campus.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Tami L. Moore, Associate Professor of Higher Education and Student Affairs, Oklahoma State University–Tulsa, Main Hall 2439, 700 N. Greenwood Avenue, Tulsa, OK 74106. Phone: (918) 549-1172. Email: tami.moore@okstate.edu

Abstract

Public deliberation, as a general approach to exploring complex issues facing geographically defined communities as well as increasing student civic engagement, has gained standing in recent years as a civic engagement tool on college campuses. Everyday Democracy’s Dialogue to Change (D2C) program provides a process through which participants deliberate and, most importantly, act toward change to address locally identified issues of concern in the campus-as-community. The purpose of this article is twofold: to describe Cowboys Coming Together, a local implementation of D2C at Oklahoma State University, and to present findings from the initial research exploring the influence of change-oriented deliberative approaches on individual participants and the campus-as-community.

Cowboys Coming Together: Campus-Based Dialogues on Race and Racial Equity

On March 21, 2019, President Donald Trump signed an executive order calling for federal agencies to ensure freedom of speech at public colleges and universities (McMurtrie, 2019, para. 2). Over the subsequent few days, journalists and other commentators writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education drew explicit connections between the order and the administration’s earlier critiques of campus officials who had cancelled or otherwise interfered with public speeches to be delivered by individuals holding politically or religiously conservative points of view, or limited the ability of students to disseminate information representing such views. Nicholas Dirks, former chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley, framed these moves as part of a larger “assault on the university” (Fischer, 2019, para. 4) reflecting increased public skepticism and mistrust. Much of the debate around this issue has centered on the line between protected speech and hate speech, a difficult distinction. For instance, a social-media post including racial slurs does fall within an individual’s right to free speech; however, these same words are also detrimental to efforts to build community and promote working across differences to address wicked problems.

Public deliberation, as a general approach to exploring complex issues facing geographically defined communities as well as increasing student civic engagement, has gained standing in recent years as a civic engagement tool on college campuses (Harriger & McMillan, 2007; Harriger et al., 2016; Shaffer et al., 2017; Thomas & Levine, 2011). The goal of public deliberation is to achieve progress toward a shared sense of direction or purpose, not consensus or complete agreement on particular solutions. Deliberation also emphasizes the common good rather than the individual, resulting in policy outcomes that benefit a wider range of the population (Harriger & McMillan, 2007, p. 22). College campuses—both as learning and relational spaces, and as physical communities and spaces in and of themselves[1]—comprise fertile environments for building understanding and common purpose. Yet, what is missing from the deliberative approach, as it has typically been employed as a civic engagement tool, is a specific push to act toward change based on new shared understandings. In an increasingly polarized political climate (Dionne, 2012; Fiorina, 2013; Galston, 2010; Mendelsohn & Pollard, 2016; Wolfson, 2006), students and community members need opportunities to not only hear one another’s views, but also explore differences productively and then act together toward the common good (DeLaet, 2015; Shaffer et al., 2017). Everyday Democracy’s Dialogue to Change (D2C)[2] program offers a process through which participants deliberate and, most importantly, act toward change to address locally identified issues of concern in the campus-as-community. The purpose of this article is twofold: to describe Cowboys Coming Together (CCT), a local implementation of D2C at Oklahoma State University (OSU), and to present findings from the initial research exploring the influence of change-oriented deliberative approaches on individual participants and the campus-as-community.

Employing Dialogue to Change

Cowboys Coming Together 2018 used D2C to support a community dialogue on race and racial equity addressing the tense environment around race and ethnic relations on campus resulting from two incidents of racially charged hate speech posted to social media by OSU students on the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday in 2017, and a third similar post by a student in mid-January 2018. “Hate speech” is the language frequently used in the OSU community—particularly by African American people and their allies—to describe these incidents. Such an application of this term would align, for example, with the American Library Association’s (ALA’s) definition: “Generally, . . . hate speech is any form of expression through which speakers intend to vilify, humiliate, or incite hatred against a group or a class of persons.” However, according to the ALA, “under current First Amendment jurisprudence, hate speech can only be criminalized when it directly incites imminent criminal activity consisting of specific threats of violence targeted against a person or group.” Social-media posts featuring racist tropes, such as those posted by OSU students in 2017 and 2018, do not meet the legal standard for hate speech, where those exist. There is no definition of hate speech under U.S. federal law. Both the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation define hate crimes[3]; however, “neither go[es] so far as to provide a distinct definition of hate speech, with the FBI stating ‘hate itself is not a crime’—and the FBI is mindful of protecting freedom of speech and other civil liberties” (S. Perez, personal communication, May 26, 2020). Oklahoma State Statute §21-850 (“Malicious intimidation or harassment because of race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin or disability”) does address hate crimes, emphasizing “the intent to incite or produce, and which is likely to incite or produce, imminent violence.”[4]

Those establishing law and legal precedent in Oklahoma have taken a similar position, balancing protection from hateful language with freedom of speech. Writing in the Oklahoma Bar Journal, Rick Tepker (2017) began an examination of cultural and legal precedents related to hate speech by pointing out the deep commitment to tolerance found in U.S. culture/history:

America is a culture that is more committed to tolerance of extremist speech than any other in the history of the world. And many citizens do not understand why . . . “thoughts we hate” deserve any respect, much less constitutional protection. But we the people learn . . . from “extremist” speech. . . . Hopefully, we can learn that bigotry and paranoia offer nothing that serves the welfare of the United States. (p. 943)

Following a review of 100 years of U.S. case law, Tepker offered this summary: “A dominant consensus supports a libertarian theory of expressive liberty. Existing doctrine developed over the past half-century stands in the way of overzealous regulation. Our law protects the thoughts we hate, including thoughts of hate” (p. 943).

The careful work of defining hate speech here contextualizes OSU officials’ response to these actions. University leaders prioritized the right to free speech in their statements following each event. In 2017, OSU president Burns Hargis referred to the posts as “racially-insensitive,” praised students’ silent protest as “an example of how to address inclusion, diversity and equality on campus,” and issued a formal statement denouncing “intolerance or discrimination of any person or group” as “unacceptable on this campus or in our society” (Jones, 2017). Following the 2018 incident, Hargis’ statement included slightly stronger language, calling the “racially charged social media post . . . unacceptable and disturbing.” Hargis continued, “It is a shame that [the student] would exercise his right of free speech in a hurtful and insensitive way” (OSU, 2018). Students, staff, and faculty received these official statements with a range of emotions, from frustration to anger. Their emotions may be best understood against the backdrop of the 2015 expulsion of two University of Oklahoma students who were recorded leading a chant that included racist language (Fernandez & Perez-Pena, 2015). Many in the OSU campus-as-community expected the same decision in the Stillwater cases and expressed frustration when the students were not disciplined through the university’s student conduct process.

Beyond the capacity to respond to specific events or persistent issues within the campus-as-community, CCT met a need within the OSU community to address difficult issues using an approach aimed at sustainable change. More generally, CCT also presents an ideal opportunity to explore the effectiveness of a campus deliberative dialogue program in facilitating civil discourse and engagement among diverse groups around issues that affect the learning environment and campus climate at a large land-grant university.

The Cowboys Coming Together dialogue program reflects four fundamental assumptions: (1) the preponderance of empirical evidence about how college affects students underscores the critical importance of fostering an inclusive campus climate, particularly for students who identify with historically minoritized racial/ethnic, gender, and other identities (Mayhew et al., 2016); (2) institutions of higher education have an opportunity to support students’ development as change agents in communities and workplaces (Hoffman, 2015; Moore, 2014; Ramaley, 2016); (3) anyone within the campus-as-community can create change; but (4) how they go about this work should differ according to the desired outcome (Kezar, 2018).

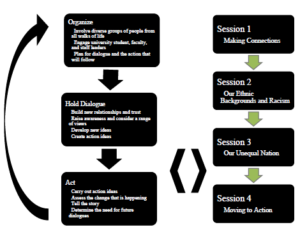

Participants in the CCT program met over time (in this case, 4 weeks), allowing people to develop trust, build relationships, and gain a shared understanding of the issue under discussion. In the 2018 dialogues described in this article, trained facilitators guided and managed the discussions, making room for all voices as group members worked through an issue discussion guide designed specifically for the OSU community to develop an action plan intended to address racism and racial equity on campus. In the first session, group members created ground rules and a framework to help make the conversation work for everyone. People began with personal stories and then moved on to a discussion of the impact of systemic racism, incorporating U.S. Census data and other relevant factual material into the conversation. The CCT utilized the guide published by Everyday Democracy, Facing Racism in a Diverse Nation (Abdullah & McCormack, 2008), in which the authors do not define racism or systemic racism but rather provide examples. In Session 2, facilitators led participants in an exercise aimed at developing a common understanding within the group of keywords, including racism, institutional racism, discrimination, stereotyping, and prejudice. As noted in the facilitator notes for Part 3 of this session, “If more information is needed,” participants are invited to “bring definitions of the words to the next session” (p. 15), along with examples of these words from radio, television, and newspapers. Facilitators introduced Session 3, entitled “Our Unequal Nation,” in the following way: “For next week’s session, the group will take part in an activity about advantages and disadvantages based on race or ethnicity.” This third session included a discussion based on 2000 U.S. Census data reflecting the extent to which “people in our country are (still) behind in areas like education, health, and employment.” Dialogue participants examined these issues from diverse viewpoints, considered many possible approaches, and ultimately developed ideas and plans for action and change in order to improve the campus climate for all community stakeholders. Figure 1 illustrates the three phases of the CCT dialogue to change program.

Figure 1

Overview of the Dialogue to Change Process

Organize

- Involve diverse groups of people from all walks of life

- Engage university student, faculty, and staff leaders

- Plan for dialogue and the action that will follow

Hold Dialogue

- Build new relationships and trust

- Raise awareness and consider a range of views

- Develop new ideas

- Create action ideas

Act

- Carry out action ideas

- Assess the change that is happening

- Tell the story

- Determine the need for future dialogues

Session 1

- Making Connections

Session 2

- Our Ethnic Backgrounds and Racism

Session 3

- Our Unequal Nation

Session 4

- Moving to Action

Studying Dialogue to Change

What we learned from the Cowboys Coming Together experience, and the program evaluation and research efforts, speaks to the current and traditional scholarship about students’ civic development (Battistoni & Longo, 2011; Bryant et al., 2012; Colby et al., 2010; Longo & Gibson, 2011; Mayhew et al., 2016) as well as organizational change for social transformation in higher education (e.g., see Barnhardt, 2017; Dugan, 2017; Kezar, 2018; Kovacheff-Badke, 2017). An interdisciplinary and intergenerational research team including masters- and doctoral-level students-as-[research] colleagues (Longo et al., 2016), staff, and faculty worked alongside CCT organizers to design and implement the first phase of a longitudinal research project exploring the impact of deliberative dialogues on student success and campus climate. Three research questions (RQs) guided the design of this multi-phase convergent parallel mixed-methods study (Creswell, 2014):

RQ1: What is the impact of participation in a dialogue to change program on members of a land-grant university community?

RQ2: How does participation in a deliberation program impact campus culture and student experiences?

RQ3: How does deliberative dialogue impact a university community’s capacity for change?

Empirical findings in this article explore the impact of the CCT program on students as measured by changes in social capital, civic agency, and knowledge and attitudes related to issues of race and racial equity in the OSU community. The conclusions presented in the article emerged from a contextualization of the empirical analysis within a historical narrative of race, integration, and racial equity in the OSU campus-as-community.

Data and Methods

This ongoing study employs multi-phase convergent parallel mixed methods (Creswell, 2014) in examining the impact of participation in Cowboys Coming Together on student success, campus climate, and the institution’s capacity for organizational learning and change. Researchers collected data representing multiple perspectives on these phenomena: oral histories and archival documents related to the experiences of students of color at OSU; individual and group interviews with members of the OSU community who volunteered to participate in the CCT dialogue program; and survey data exploring changes in participants’ civic attitudes, behaviors, and networks associated with participation. The following sections summarize the methods.

Historical Methods

Harvey (1993) argued that it is impossible to separate what happens from the place where it happens; in the context of the Cowboys Coming Together program, place extends to the historical, sociopolitical, and cultural aspects of a particular locale. Further, the stories that institutions tell about themselves influence nearly every aspect of a campus community (Clark, 1972). With these two ideas in mind, the two members of the research team who are trained historians explored a variety of primary and secondary sources, including oral histories, archived student publications, contemporary and retrospective stories from area media outlets, and the university’s Centennial Series volumes, which tell the story of OSU’s first 100 years. Drawing from these diverse primary and secondary sources allowed us to contextualize CCT vis-à-vis not only OSU’s telling of its own history (e.g., Kamm, 1990; Kopecky, 1990; Murphy, 1988; Rulon, 1975), but also the stories that former students and faculty have told (e.g., Davis, 2009; Latimer, 2008; Wetzel, 2010) about their time at OSU.

Participant and Facilitator Surveys

Two surveys were administered to participants, and one survey was administered to facilitators. Data on participant demographics, their involvement in campus organizations, indicators of social capital and civic participation, and their evaluation of the CCT program were collected using two online surveys administered using Qualtrics. Facilitator experiences were captured using a paper evaluation survey that was administered at the action forum following the completion of all five CCT dialogue sessions.

The post-dialogue participant survey was used to gather demographic information, to evaluate the outcomes of the CCT program, and to measure participant civic engagement outside of CCT. Civic engagement was measured through 12 questions adapted from the Social Capital Community Survey (Saguaro Seminar, 2006). These questions asked about CCT participant behaviors such as whether they attended a rally or a speech, signed a petition, and/or volunteered. Slightly less than half, or 30 of the 74, CCT participants completed evaluations at the event, representing a 41% response rate. Appendix A includes the participant evaluation instrument.

A second survey was administered to gather the campus organizational affiliations of CCT participants which were used to determine the organizations that were central to the CCT network. The second survey also included questions on participants’ self-efficacy and trust which were adapted from the Social Capital Community Survey. Participants shared the number of campus organizations they were currently actively involved with, as well as how many they had been involved with during their overall time at OSU. Appendix B includes the second survey instrument.

The social network portion of the second survey was an open-ended bipartite questionnaire (Borgatti et al., 2018). Each respondent was also asked to provide the names of the campus organizations in which they were actively involved. Open-ended surveys can produce errors due to respondents’ memory and accuracy, but in this study, using them meant that the researchers did not need to provide a closed list of every campus organization to participants. Because the program was developed to address an immediate need, the survey was not able to gather information about how well participants knew each other; instead, organizational memberships were the only network-related data gathered.

Facilitator experiences were captured using an evaluation survey administered at the action forum. Six of the eight facilitators attended the action forum and completed evaluations, representing a 75% response rate. Survey questions asked about their perceptions of how the dialogues went, their satisfaction with the experience of serving as a facilitator, and their thoughts about the future of the CCT program. Appendix C includes the complete facilitator survey.

Individual and Group Interviews

Student, faculty, and staff representing all five dialogue groups took part in one of two 60- to 90-minute group interviews (n = 8) and individual interviews (n = 1) of 7–10 minutes on the day of the action forum, 1 week following the end of the dialogue phase. Researchers conducted a third group interview with six of the 10 facilitators 2 weeks after the conclusion, using the group interview protocol included in Appendix D. Audio recordings of the group interviews were transcribed verbatim, with reference to the video recording to identify/confirm the identity of a speaker or otherwise check the accuracy of the transcription. Researchers prepared written summaries of the interviews, and video recordings of the individual interviews will be used to promote future rounds of the dialogue program.

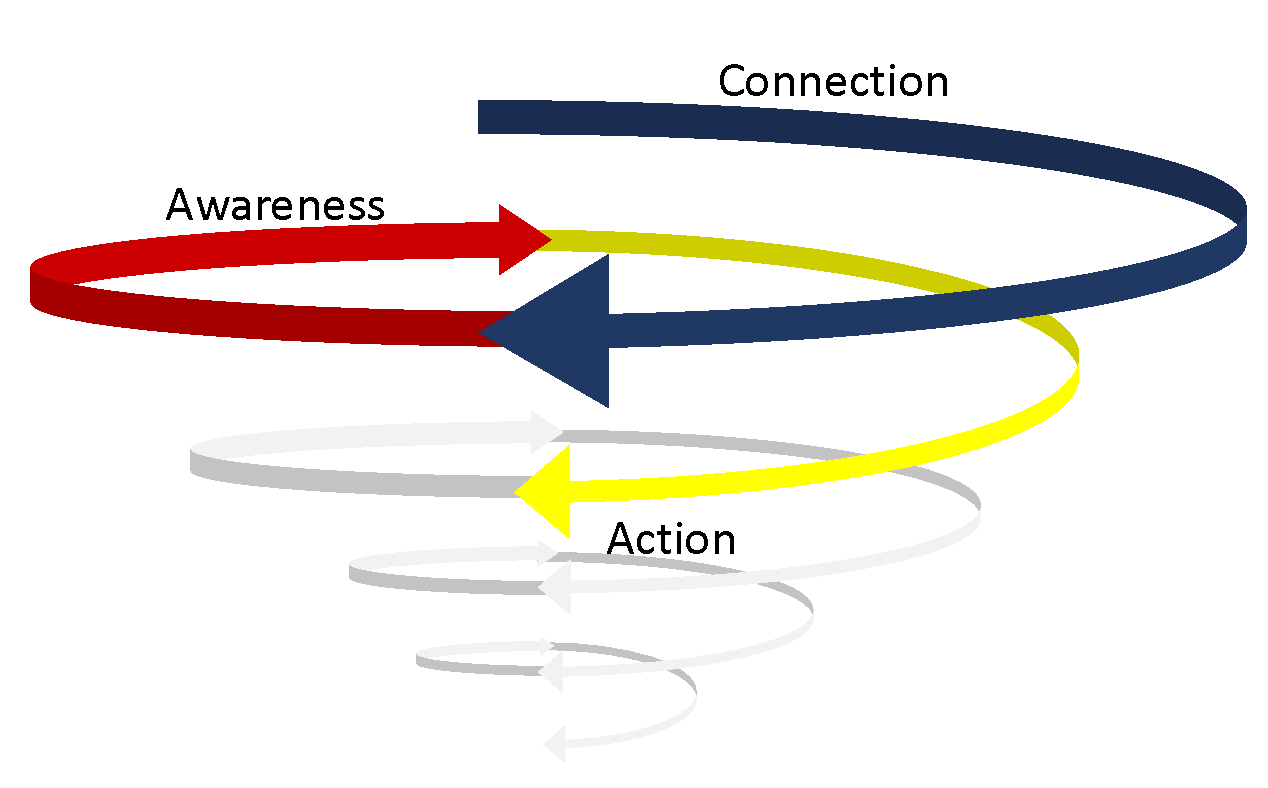

Three of the seven authors analyzed the qualitative data, working together in phases. An initial round of in vivo coding (Saldana, 2009) conducted by one author revealed eight emergent codes, which collapsed into five categories. The other two researchers read the complete dataset, developing initial impressions of “the story of the data” (Moore et al., 2013, p. 31; see also Taylor & Bogdan, 1998) as it began to emerge The team first engaged in a prolonged discussion about the consistencies and inconsistencies among each member’s initial understandings. Careful attention to participants’ use of language and the application of Jackson and Mazzei’s (2012) “thinking with theory”—grounded in hermeneutics (von Zweck et al., 2008), identity development and race relations on campus (Cabrera, 2018; Harper, 2013; Linley, 2018; Mayhew et al., 2016), and deliberative democracy (Harriger et al., 2016; Longo & Gibson, 2011; McCauley et al., 2011)—suggested that categories could be further synthesized. This revealed patterns of deepening engagement by participants in the deliberative process: coming together for connection, expanding awareness, and moving into action.

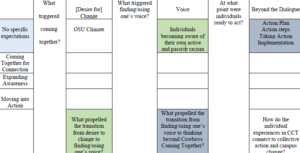

Scholarship related to the experiences of students of color at predominantly/historically White institutions, such as OSU, suggested that Black participants’ experiences may have been qualitatively different from those of the White participants (Harper, 2013; Ledesma, 2016; Linley, 2018). The team then conducted a second round of coding to uncover whether or how participants’ experiences differed according to their racial identity and/or their role/status within the university. Responses to interview prompts differed very little among students, staff, and faculty participants. Race, however, did prove to be a salient distinction among participants. In this second analytical phase, three themes emerged, connecting a specific and iterative sequence of experiences (von Zweck et al., 2008) across differences in racial identity and role/status within the OSU community: (the desire for) change; (finding/using one’s) voice; and thinking/moving beyond the dialogue experience. A third phase of the analysis consisted of bringing together the patterns and themes. How, for example, did participants explain the influence of their expanding awareness of self or others on a deepening commitment to call out discrimination and hate speech within themselves and others? Figure 2 reflects the patterns of deepening engagement as a drilling down through any one specific category, thereby encouraging the individual to shift focus to a new aspect of the experience. Finally, researchers conducted a fourth round of analysis using the cells shown in Figure 2 as categories for the data.

Figure 2

Patterns of Deepening Engagement by Participants in Three Aspects of the Dialogue to Change Model

|

What triggered coming together? |

[Desire for] Change |

What triggered finding/using one’s voice? |

Voice |

At what point were individuals ready to act? |

Beyond the Dialogue |

|

|

No specific expectations |

OSU Climate |

Individuals becoming aware of their own active and passive racism |

Action Plan Action steps Taking Action Implementation |

|||

|

Coming Together for Connection |

||||||

|

Expanding Awareness |

||||||

|

Moving into Action |

||||||

|

What propelled the transition from desire to change to finding/using one’s voice? |

What propelled the transition from finding/using one’s voice to thinking beyond Cowboys Coming Together? |

How do the individual experiences in CCT connect to collective action and campus change? |

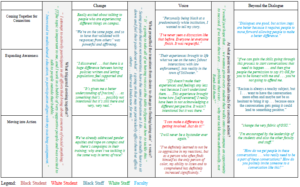

In a final round of qualitative data analysis, we refined the definitions of the categories to more accurately represent participants’ experiences and attitudes about participating in the dialogues and how this experience would potentially influence their future involvement on campus. Three themes as well as common patterns in participant experiences emerged from the data. Figure 3 illustrates excerpts from the dataset which illustrate the progression from connections with other concerned community members through a desire for action based on the dialogue experience.

Figure 3

Participants’ In Vivo Descriptions of Deepening Engagement and Desire for Action as a Result of CCT Participation

|

What triggered coming together? “I attempt to actively participate in all efforts that bring about concern of racial anything.” “[T]he topic is important to me, and I work in a bubble of very supportive people and was excited to talk to people outside that bubble.” “Interested in multicultural education, so participation aligns with my teaching assignment.” |

Change |

What propelled the transition from desire to change to finding/using one’s voice? “It’s going to take all of us having voices at the table to figure out how to tackle this.” “Seeing people that are not minorities, have the same frustration as I do. . . . to actually have to sit down and feel their pain about what’s going on that may not particularly affect them but affects others . . . that was kinda new for me.” |

Voice |

At what point were individuals ready for concrete action? “I would just hope that . . . we wanna given every student that walks onto this campus an opportunity to succeed. If we know there are . . . problems that exist . . . why not tackle them authentically, not Band-Aid them?” |

Beyond the Dialogue |

|

|

Coming Together for Connection |

Really excited about talking to people who are experiencing different things on campus. “We’re on the same page, and so to have that validated with responses from others” was powerful and affirming. |

“Personally being black at a predominantly white institution, I wanted to tell my story. “I’ve never seen a discussion like that before. Everyone let everyone finish. It was respectful.” |

“Dialogues are good, but action steps are better because it requires people to move forward allowing people to make a better difference.” |

|||

|

Expanding Awareness |

“I discovered . . . that there is a huge difference between having policies written and letting populations feel supported and included.” “It’s given me a better understanding of [racism] . . . as something that’s . . . possibly not intentional but it’s still there and very, very real.” |

“Their experiences brought to life what we see on the news [about interactions with law enforcement], into reality in the town of Stillwater.” “[I]t doesn’t make their experiences and feelings any less real because I can’t understand them. . . .This experience brought home how [self-centered] I really have been in not acknowledging a different perspective. It wasn’t intentional but it was there.” |

“if we can gain the skills going through this process to start conversations that need to happen . . . and then give people the permission to say it’s OK for you to be honest with me and . . . you’re not going to offend me. “Racism is always a touchy subject, but I . . . want to have the conversation more often and maybe not be as hesitant to bring it up . . . because once the conversation gets going it could lead to something positive.” |

|||

|

Moving into Action |

We’ve already addressed gender equities and rape on campus and there’s campaigns in their training; why aren’t we tackling it the same way in terms of race? |

“I can make a difference by getting involved. Just do it!” “I will never be a bystander ever again.” “I’ve definitely learned to not be so aggressive in my reactions, but as a person who often finds himself as the only person of color, my ability to listen and to comprehend has definitely increased significantly.” |

“change the very fabric of OSU.” “I’m encouraged by the leadership of the students and also the other faculty and staff.” “How do we get people in these conversations . . . who really need to be a part of these conversations? How do you politely invite someone to a conversation like this?” |

Legend: Black Student White Student Black Staff White Staff Faculty

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of CCT participants. The majority of CCT participants identified their gender as female (57%), and the groups were racially/ethnically diverse: a plurality of participants were White (47%), followed by African American (27%), multiracial (17%), Latinx (7%), and Native American (3%) participants. Politically, the majority of participants identified as liberals (63%), followed by moderates (20%) and conservatives (3%).

Table 1

CCT Participant Demographics

|

Characteristic |

Total |

% |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

13 |

43.3 |

|

Female |

17 |

56.7 |

|

Political Ideology |

||

|

Liberal |

19 |

63.3 |

|

Moderate |

6 |

20.0 |

|

Conservative |

1 |

3.3 |

|

Don’t Know |

4 |

13.3 |

|

Race |

||

|

White |

14 |

46.7 |

|

Black |

8 |

26.7 |

|

Native American |

1 |

3.3 |

|

Latinx |

2 |

6.7 |

|

Multiracial |

5 |

16.7 |

|

M |

SD |

|

|

Age |

31.83 |

11.474 |

Note. n = 30. Respondents were asked to check all racial categories that applied to them. Respondents were collapsed to “multiracial” if they checked multiple categories.

Table 2 summarizes participants’ levels of trust, self-efficacy, and campus group involvement. In general, participants reported fairly high levels of self-efficacy, with 81% of respondents believing they could at least make a moderate impact in their community. Participants also reported high levels of social trust, with 62% of respondents indicating that they believed most people can be trusted. Participants were also likely to be active in campus groups and organizations. In total, 76.2% of respondents indicated being a member of a campus group, and 52.4% of respondents indicated they were actively involved in a campus group. Those respondents who were members of campus organizations participated in an average of 2.79 groups during their time at OSU. Of those active members, respondents indicated participating in an average of 1.21 groups.

Table 2

Efficacy, Trust, and Participation in Campus Groups

|

Variable |

Total |

% |

|

Overall, how much impact do you think PEOPLE LIKE YOU can have in making your community a better place to live? |

||

|

A small impact |

8 |

19.0 |

|

A moderate impact |

18 |

42.9 |

|

A big impact |

16 |

38.1 |

|

In general, do you think that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful when dealing with people? |

||

|

You can’t be too careful |

11 |

26.2 |

|

Most people can be trusted |

26 |

61.9 |

|

M (N) |

SD |

|

|

Number of campus groups a participant had been a member of since being at OSU |

3.16 |

2.754 |

|

Number of campus groups with which a participant was currently actively involved |

1.59 |

1.341 |

Note. n = 42. For missing data related to the number of groups, an adjusted n appears.

Table 3 reports participant involvement in political and non-political engagement per the post-dialogue survey. A majority reported volunteering in the community (80%), voting in an election (60%), and working informally with others to solve a community problem (63.3%) in the previous year. The lowest reported engagement activities included writing a letter to a newspaper (6.7%) and working for a political party (6.7%).

Table 3

Civic Participation

|

Form of Engagement |

Total |

% |

|

Have you written to one of your elected representatives in the past year? |

9 |

31.0 |

|

Have you attended a rally or speech in the past year? |

12 |

40.0 |

|

Have you attended a public meeting on town or school affairs in the past year? |

10 |

33.3 |

|

Have you signed a petition in the past year? |

15 |

50.0 |

|

Have you served on a committee for some local organization in the past year? |

10 |

33.3 |

|

Have you voted in an election in the past year? |

18 |

60.0 |

|

Have you volunteered in the past year? |

24 |

80.0 |

|

Have you written a letter to the paper in the past year? |

2 |

6.7 |

|

Have you worked for a political party in the past year? |

2 |

6.7 |

|

Have you been a member of some group like the League of Women Voters or some other group which is interested in better government in the past year? |

4 |

13.3 |

|

Have you served as an officer of some club or organization in the past year? |

12 |

40.0 |

|

Have you worked informally with others to solve a community problem in the past year? |

19 |

63.3 |

Note. n = 29. One respondent did not answer the set of questions on civic participation.

Network Characteristics

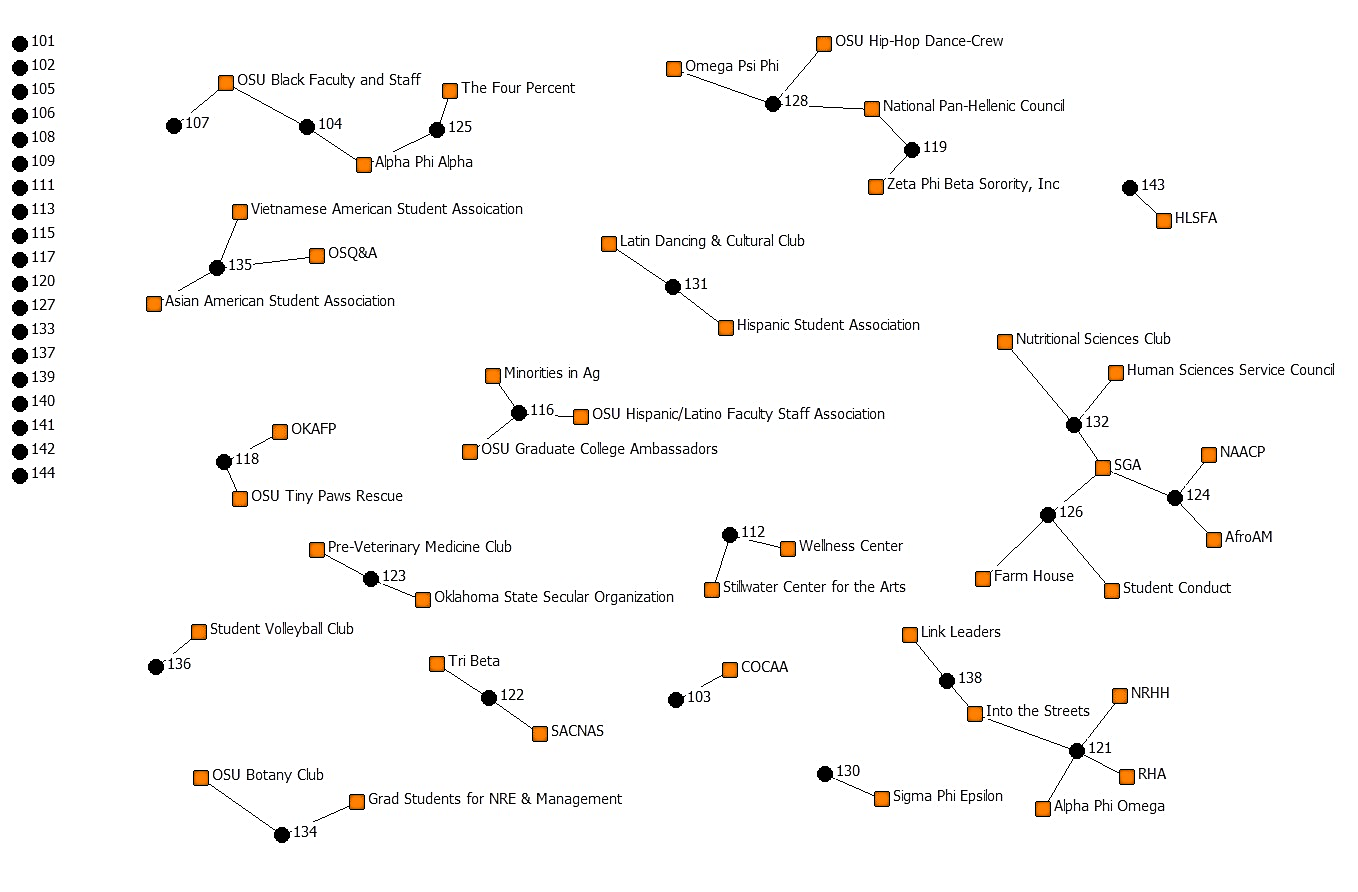

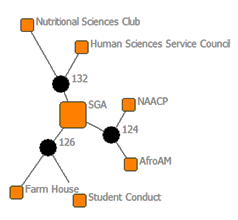

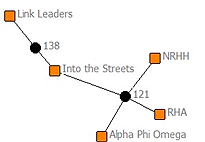

The results of the social network survey provided a unique perspective on the network structure of CCT. The bipartite network map (shown in Figure 4) offers an overview of the participants’ connections to various campus organizations. Furthermore, bipartite network centrality was calculated for the organizations in order to determine which campus organizations were most connected through CCT. Finally, the individuals in the network were examined to determine how they potentially bridged campus organizations through their participation in the CCT program.

Bipartite Network Map

Figure 4 depicts a bipartite network map of responding participants’ organizational memberships, with squares representing campus organizations and circles representing CCT participants. Generally, bipartite network maps reveal how participants are connected to each other through the organizations with which they are involved (Borgatti & Everett, 1997). Respondents included students, staff, and faculty who participated in CCT[5]; 52.4% of participants indicated being actively involved in a campus organization (represented as circles attached to a square), while 46.7% of participants were not actively involved in an organization (represented by unattached circles to the side of the map). In total, 42 campus organizations were represented in the first round of CCT, ranging from student governance (i.e., Student Government Association [SGA], Residence Hall Association, National Pan-Hellenic Council [NPHC]) to fraternities, sororities, and academic clubs. Multicultural or cultural organizations were common, representing historically Black fraternities and sororities (i.e., Omega Psi Phi, Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Alpha Phi Alpha) and their governing council (NPHC), and solidarity groups such as the OSU Black Faculty and Staff Association, Asian American Student Association, and The Four Percent,[6] an emerging organization of Black students. Additionally, it should be noted that the OSU Black Faculty and Staff Association is an exclusively faculty/staff advocacy group, which was connected to student organizations through participants.

Figure 4

Bipartite Network Map of CCT Participant Membership in Campus Organizations

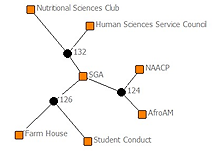

Network Centrality

Within a campus-as-community such as OSU, one might reasonably expect students and staff to interact with one another in specific student organizations and activities but not all activities. In other words, not every student/participant who is active in a campus organization will know all staff who work in particular student affairs offices. Students also connect with staff and faculty through their academic pursuits, but these relationships are somewhat localized around academic advising and coursework required for a particular degree, connecting other individuals who are in turn connected to other organizations. We used the concept of network centrality to determine the structural importance of a specific node—an organization populated by combinations of students, staff, and/or faculty—based on its position within the larger network (Borgatti et al., 2018). The most central organizations in the OSU campus-as-community social network are part of the SGA cluster, as highlighted in Figure 5. Centrality, here, represents how close an organization is to a central node, connecting multiple individuals. These are the organizations that have the most access to other organizations within the CCT network. The SGA is the most central organization in the larger network, connecting the remaining most central organizations (see Table 4). In turn, these relationships create a cluster of centrality. In light of the SGA’s centrality, the CCT program will be less important to the SGA than other organizations for establishing new connections and partnerships. The SGA cluster, in turn, is less impacted by CCT compared to less central organizations such as the Greek-letter organizations or student organizations affiliated with an academic department or college.

Figure 5

Central Organization Cluster, with Larger Sizes Representing Greater Centrality

Central Organization Cluster, with Larger Sizes Representing Greater Centrality

Table 4

CCT Central Organizations

|

Organization |

Eigenvalue |

|

Student Government Association |

0.775 |

|

FarmHouse |

0.258 |

|

Student Conduct |

0.258 |

|

NAACP |

0.258 |

|

Afro-AM [Afro-American Student Association] |

0.258 |

|

Human Sciences Service Council |

0.258 |

|

Nutritional Sciences Club |

0.258 |

People Bridging Organizations

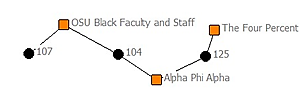

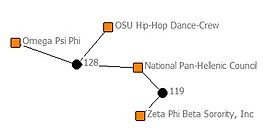

As Figure 6 shows, the CCT participants bridged certain campus organizations. These bridging individuals connected two or more campus organizations into a cluster. For example, an SGA cluster pulled together three students who were all connected to additional organizations (i.e., FarmHouse Fraternity, Student Conduct, Nutritional Sciences Club, Human Sciences Service Council, NAACP, and AfroAM). Other clusters, such as participants 125, 104, and 107, showed a connection of three organizations focused on cultural issues or solidarity (i.e., The Four Percent, Alpha Phi Alpha, and the OSU Black Faculty and Staff Association). Omega Psi Phi, a historically Black male fraternity, and Zeta Phi Beta, a historically Black sorority, were connected through their governing council, the National Pan-Hellenic Council.

A number of organizations bridged the connection between two participants, as highlighted in Figure 6. The SGA was the most prominent bridging organization, connecting five student organizations. Alpha Phi Alpha bridged two African American organizations, while the NPHC bridged the male NPHC fraternity (Omega Psi Phi) with the female NPHC sorority (Zeta Phi Beta).

Figure 6

Clusters of Campus Bridging Organizations

Participant Outcomes

Participants responded to four survey questions about outcomes resulting from participation in the CCT (see Table 5). In general, respondents felt that participation in CCT had a positive effect on them, and no one indicated that they had a negative experience. It is particularly noteworthy that 93% of respondents felt that participation had increased their understanding of others’ attitudes and beliefs, and 90% felt that participation had increased their ability to communicate more effectively with people who have beliefs different than their own.

Table 5

Participant Outcomes

|

Outcome |

Total |

% |

|

What effect, if any, has CCT had upon your ability to discuss issues openly and frankly? |

||

|

No change |

8 |

26.7 |

|

Increased |

21 |

70.0 |

|

What effect, if any, has CCT had upon your understanding of your own attitudes and beliefs? |

||

|

No change |

6 |

20.0 |

|

Increased |

23 |

76.7 |

|

What effect, if any, has CCT had upon your understanding of others’ attitudes and beliefs? |

||

|

No change |

1 |

3.3 |

|

Increased |

28 |

93.3 |

|

What effect, if any, has CCT had upon your ability to communicate more effectively with people who may have different beliefs? |

||

|

No change |

2 |

6.7 |

|

Increased |

27 |

90.0 |

Note. n =29. One respondent did not answer the set of questions on civic participation.

Findings from the Historical Analysis

Cowboys Coming Together began, in part, in an effort to provide a space for members of the OSU campus-as-community to process thoughts, feelings, and ideas for change in response to the second instance of racially charged social-media posts on the MLK holiday in 2017 and 2018. To understand the culture and climate of the OSU Main Campus, located in Stillwater, Oklahoma, in spring 2018, one would be well served to consider the history of race, integration, and racial equity since the integration of the OSU campus in 1949 by Nancy Randolph Davis. This brief and incomplete history[7] of the experiences of Black students in the OSU community is unsettling in the sameness of many of the stories recorded from one day to the next, much less one decade to the next.

Consider, for example, Patrice Latimer, the first African American president of OSU’s Student Government Association elected in 1973. On March 8, 2017, Latimer spoke with Erica Stephens, the second African American SGA president who had just been elected 2 days earlier. During their call, the two women found many similarities between their campaign experiences: Both had White male running mates at a time when the OSU campus and the United States were experiencing long-dormant political divisions, and both offered a campaign message of unity to a campus community recently divided by racially insensitive incidents (Medill, 2017). In 2002, the Southern Poverty Law Center included on its website photographs from an OSU fraternity party as an example of hate crimes occurring in the United States. At the time, a senior OSU administrator rationalized the fraternity members’ costumes depicting a lynching as the result of “ignorance,” a word that resonates in the present. Wilbanks Smith, the OSU football player who delivered a violent tackle against Drake University fullback Johnny Bright in 1951, insisted in a 2012 interview that the famous incident was not motivated explicitly by any racist attitudes of his own, but rather by instructions from his head coach (Fredrickson, 2012). Those responsible for the 2017 and 2018 social-media posts apologized the next day, taking “full responsibility” for their “thoughtless” post, even though it was “never [their] intention to cause harm” (Britton, 2017), and acknowledged “showing an extreme lack of character . . . [for which they were] truly sorry” (Gregory, 2018). OSU’s president responded via Twitter in 2017, calling the Instagram post “thoughtless and insensitive.” His statement following the 2018 SnapChat post including a racial slur expressed sadness that the student responsible “would exercise his right of free speech in a hurtful and insensitive way” (Gregory, 2018). Each year, OSU’s president spoke forcefully about the OSU community’s commitment to fighting intolerance (Britton, 2017; Gregory, 2018).

Since January 2017, African American students and their allies have organized in multiple groups to call for changes by university administrators to address what they see as either causes or effects of racism and hate speech. All groups have called for establishing mandatory diversity training for students; other ideas have included amending the Student Code of Conduct to address “racially insensitive and/or racist rhetoric and behavior,” hiring more faculty of color, and a joint statement from senior administration “detail[ing] plans to enhance race relations” (Britton, 2018, para. 4) on campus.

Connection, Awareness, and Action: Findings from the Qualitative Analysis

Students, faculty, and staff (n = 8) representing all five dialogue groups, and six of the 10 facilitators, took part in group and individual interviews following the dialogue phase of CCT. As a result of in vivo coding (Saldana, 2009), a unique set of patterns and themes emerged from the data, reflecting attitudes, emotions, and experiences shared among participants, independent of their role within the campus-as-community.

Three themes emerged from the data as a result of in vivo coding (Saldaña, 2009): a common desire to effect change, finding/using one’s voice to influence plans for change, and a desire to move beyond the initial dialogue, either by broadening or changing the topic, or moving toward action based on the work of the dialogue group. Data analysis further revealed a specific pattern in participants’ experience of the dialogue process present in each of the three themes. The data suggest that many people initially chose to participate in the Cowboys Coming Together dialogue program because they were concerned about the impact of recent incidents on individuals and the campus-as-community as a whole, and they wanted to be part of making a change. The commitment to making change may have been more deeply held by some participants than others, but all of them spoke to a strong interest in connecting with others who shared their concerns and a desire to see something different Figure 7 depicts a progression from making a personal connection to awareness of others’ experiences, to a desire for action.

Figure 7

Patterns in Participants’ Experience of the Dialogue to Change Process

Within the three themes—desire for change, finding/using one’s voice, and thinking/acting beyond the dialogues—we found evidence of individual and collective movement through a pattern of connection, awareness, and action (see Figure 3 for excepts from the dataset which further illustrate participants’ progression). Connections were made and, in the process, individuals expanded their awareness of themselves and others, and—since they felt more connected and had tapped into a richer awareness of issues and possibilities—they deepened their commitment to the dialogue to action model.

The Evolution of a Campus-Based Dialogue Initiative

The empirical findings presented earlier reflect research conducted as part of a systematic evaluation of the inaugural dialogues funded by Campus Compact’s Fund for Positive Engagement. The research and evaluation team included members of the core organizing team as well as other faculty and graduate student partners with intersecting research interests.[8] We anticipate that some readers came to our work out of an interest in starting a similar initiative or learning from the successes and challenges that Cowboys Coming Together faced over time. We would be remiss not to offer an overview of the core team’s[9] work to sustain dialogue on campus as well as an honest assessment of the challenges we continue to navigate. Therefore, in this article, we explore barriers to and supports for the work of promoting a dialogue to change approach to strengthening campus culture, key takeaways from these experiences, and some practical recommendations for sustaining campus-based dialogue to change initiatives.

Sustaining the Initiative

As of this writing, the campus-based dialogue initiative discussed here is 3 years old. Since January 2018, the core organizing team for Cowboys Coming Together has hosted three annual dialogue cycles. Through evaluations and the findings reported earlier, participants indicated their belief in the necessity of continuing the focus on facing racism in Year 2. Based on the low participation numbers for the 2019 dialogues, the CCT core team members decided in 2020 to shift the focus of topics to the impact of social media on the campus-as-community. The team conducted a National Issues Forum-style concern-collecting process (Rourke, 2014),[10] soliciting input on three questions:

- When you think about the influence of social media on the OSU community, what concerns do you have?

- What concerns do you hear others around you expressing about the influence of social media on the OSU community?

- What do you think should be done to address the influence of social media on the OSU community?

Initial interest in this topic was high: 459 people responded to the three-question survey distributed through the all-campus email listserv. Approximately 30 members of the OSU community, primarily students, participated in one of three focus groups hosted by CCT core team members, using these three questions as the group interview protocol.[11]

Core team members and OSU faculty who study social media worked together, following the NIF process outlined by Rourke (2014), for the initial analysis of the data. Upon identifying groups of like concerns, or themes, in the data, we drew on these themes to inform the focus for sessions designed according to Everyday Democracy’s dialogue to change model. The result was a four-session dialogue series including sessions on the role of technology in individual lives, exploring attitudes about social media expressed by members of the OSU campus-as-community; deepening understanding of how concerns in the OSU community relate to concerns expressed in the media about what happens when people across the United States and around the world connect via social-media platforms; and setting priorities for action.

Thirty students, staff, and faculty registered for the 2020 dialogues, which began as face-to-face events and—in response to the university’s cancellation of all in-person events during the first phase of the COVID-19 restrictions—moved to virtual gatherings beginning in Week 3. The implementation of shelter-in-place precautions drastically reduced participation in the action forum and effectively undermined the action phase of these third dialogues. Those who did participate in the forum agreed that the dialogues themselves could be an effective response to the social isolation associated with social-media platforms as the primary venue for interacting with others. Two participants have joined the core team, investing their efforts toward change in strengthening the infrastructure for this primarily volunteer effort.

Supports for Dialogues

Everyday Democracy’s dialogue to change model begins with an organizing phase, a time for leaders to build support by engaging with a broad representation of the campus-as-community to recruit leaders and participants from around the campus. At OSU, the dialogue initiative known as Cowboys Coming Together and then as OSU Dialogues4Change benefited from support by administrators around campus to secure adequate funding and to support participant recruitment, and from participation by individuals with broad-based connections.

Ultimately, the dialogue process yields the most impactful results when people who do not ordinarily interact with one another come together. Cowboys Coming Together emerged from the independent efforts of individuals in two academic colleges and the Division of Student Affairs. Beginning in January 2016, students, professional staff, and faculty with connections to OSU’s Higher Education and Student Affairs program started a book discussion group focused on student leadership development. In spring 2017, Mike Stout[12] began conversations with colleagues in the College of Human Sciences about introducing the dialogue to change approach as a way to bring community-driven change to the OSU community. These two sets of actors coalesced around the Campus Compact Fund for Positive Change grant in July 2017.

In the initial organizing work, participation skewed heavily toward student affairs personnel, students, and individuals with connections to the Higher Education and Student Affairs degree program (i.e., current students and alumni). This relatively homogeneous group made intentional efforts to reach beyond their immediate functional areas when recruiting facilitators and participants. We were somewhat successful, based on the social-network analysis reported earlier.

Startup funding for the dialogues came in the form of a Fund for Positive Engagement grant from Campus Compact, awarded in August 2020. Only current members of Campus Compact were eligible to apply. After receiving notification of the award, the co-principal investigators learned that, due to financial exigencies, many administrative units within OSU had recently discontinued institutional memberships in various professional organizations, including Campus Compact. Thus, the first task upon award notification was to identify funding to renew this commitment. CCT core team members are grateful to Dr. Jason Kirksey, vice president for institutional diversity, for covering this expense, without which there would have been no Cowboys Coming Together in its current form. The Division of Institutional Diversity has continued to fund the initiative. In summer 2020, a donor established an endowed fund to provide this support in perpetuity.

Upon hearing about the initiative at a meeting of OSU’s University Network for Community Engagement, several college deans offered to underwrite the cost of the dialogues for 1 year. The core team chose to politely refuse one-time funding in lieu of maintaining a long-term relationship with Campus Compact. Several months later, when the dialogues were announced, Dr. Thomas Coon, vice president and dean of the Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources (including the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service) forwarded the announcement through the all-division listserv, including a note of his enthusiastic support for the initiative and encouraging all in the division to participate per their interest.

This strong show of support and encouragement from senior administrators secured the success of the first round of CCT dialogues. Core team members built on this success by inviting participants from Year 1 onto the core team as well as recruiting facilitators from among the first-year participants.

Challenges to Expanding Dialogue to Change

Organizers chose the dialogue to change model specifically because it was designed to facilitate a process whereby 12 to 15 people come together to create a shared understanding of a particular issue, decide upon options for action to address a root cause of the problem, and ultimately work together to enact change. The core team has, at the time of this writing, hosted three rounds of dialogues, but we have yet to witness the completion of an action item recommended by one of the groups.

More than two times as many participants engaged in Cowboys Coming Together in the first dialogue cycle as compared to the subsequent two cycles, declining from nearly 80 participants in 2018 to 30 in 2019 and 28 in 2020. Anecdotal exchanges between core team members and prospective participants during recruitment efforts in 2019 revealed some instructive patterns. Conversations about possible participation in CCT seemed more often to occur in same-race small groups than in mixed-race dyads or groups. For instance, when Black core team members staffed the information table in the student union, other Black people approached the table more readily than did Whites or their counterparts of other racial/ethnic identification. Even when a limited CCT marketing campaign did reach them, many indicated disinterest in engaging in more talk about race and what could or should be done about it within the OSU campus-as-community.

Black students in particular described experiences regarded by scholars as symptoms of racial battle fatigue, “the physiological, psychological, and behavioral strain exacted upon racially marginalized and stigmatized groups” (Smith et al., 2011, pp. 66–67).[13] To use a colloquialism, some students, staff, and faculty at OSU, by 2019, sympathized with voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s comments at the 1964 Democratic National Convention: “All my life I’ve been sick and tired. Now I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” (as cited by Browne-Marshall, 2007, p. 131).

The ad hoc nature of the dialogues has undoubtedly limited the reach and effectiveness of Cowboys Coming Together, particularly in relation to implementing action ideas following the dialogue portion of the series. Only one action group has made appreciable progress in its efforts to add the CCT dialogue to the list of professional development opportunities recognized by OSU Human Resources to satisfy requirements for a staff leadership training program. Even this work stalled when the team leader left OSU. The one idea generated through the third dialogue cycle, held in spring 2020, seems likely to succeed. Two people have been working to develop a podcast series exploring diverse perspectives on current events. Coincidentally, OSU’s student newspaper has recently expressed interest in developing its own podcast; dialogue organizers will facilitate connecting the newspaper initiative to the dialogue for change participants for collaboration. The potential for success in this possible collaboration is instructive in the similarities and differences between it and other action ideas that did not come to fruition. Groups that did not make progress usually started with equal enthusiasm and creativity, and their ideas were also directly related to some aspect of the problem as they had come to understand it through dialogue. However, these other groups were not able to gain immediate access to individuals with the resources, social capital, or authority to help effect the desired change.

Human and fiscal resources to sustain the campus dialogue initiative have been somewhat limited after the initial Campus Compact grant in Year 1. We employ food—that is, coming together for meals—as a tool to support dialogue, making the cost of small meals or snacks the primary cost of the program; the planning team gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Division of Institutional Diversity for this primary cost and for travel for conference presentations about the program.

Another very important consideration for replicating the approach to addressing racial equity described here is how and by whom the work will be done. Dedicated staff time is the most challenging aspect of sustaining this effort. The lead organizer is a (tenured) faculty member whose scholarship includes a focus on deliberative democracy as an aspect of campus civic engagement; she lists her involvement with CCT as internal service to the university. Conference presentations and refereed publications such as this one are required to make this time count in the university’s tenure and promotion process.[14] Other team members volunteer time beyond their primary roles/functions within the university community (i.e., their job responsibilities). As a result, the bulk of the work to actualize planning for the dialogues has fallen on a very small number of people. Most dialogue group members have also participated on their own time. The CCT program relies on the personal commitments of individual team members to power the initiative in the sense that there is no formal requirement or recognition for participation on the part of organizers or dialogue group members.

In fall 2020, CCT—renamed OKState Dialogues4Change (D4C)—will partner with leaders of an equity initiative within the College of Education and Human Sciences (CEHS) to offer dialogue circles for members of the CEHS community focused on addressing systemic inequities in the college. Organizers anticipate more effective change to emerge from this dialogue cycle because of the early involvement of the dean and senior administrators in D4C planning. An associate dean has been charged with overseeing activities of the initiative, and the senior leadership team announced its commitment to make change prior to entering into the collaboration with D4C. Future research should explore the ways this formal commitment supports or hinders the change component of the dialogue model.

Parameters of the Study

Following the tradition of qualitative inquiry, we set parameters for the study by addressing the positionality of the research team members. Considering the mixed-methods design employed in the study described here, we see relevance in addressing positionality in three domains: designing the dialogue experience; designing and implementing the research protocol and the research protocol; and interpreting the data.

Mike introduced the dialogue to change model to OSU/Cowboys Coming Together based on his previous experience with this approach in a community setting at another university. Tami came to this collaboration focused on exploring the connection between democratic practice, student development, and the purpose/impact of college on students as emerging civic actors. Two faculty colleagues joined this small team, contributing their expertise in educational psychology and program evaluation, respectively.

The research team that designed the study and collected and interpreted the data included a collection of individuals who differ along a number of demographic categories, including campus status, education level and experience, academic specialization and primary methodological approach, and length and depth of relationship with the institution. Seven members of the team identify as White, two as Black, and one as Asian/Pacific Islander. Two tenured and two not-yet-tenured faculty members and six doctoral students represent four fields of study. Two researchers hold degrees in history, one is trained as a sociologist, a second draws on social psychology, and a third grounds her work in qualitative methodologies. Three students currently work as university administrators in academic (n = 1) and student (n = 2) affairs; one of the faculty members previously served as a student affairs administrator on five different university campuses. One student researcher has an educational and professional background in student affairs, particularly with student organizations and civic engagement at multiple institutions. His educational background and professional experience informed the interpretation of the social network analysis and provided depth of understanding related to the nuances of the relationships among campus organizations, fraternity and sorority life, and student government.

Of the six doctoral students pursuing terminal degrees, two also hold Master of Science degrees from OSU. Tami earned her first two degrees from the institution, and she is the daughter of a spring 1957 graduate of Oklahoma A&M College; OAMC became Oklahoma State University in fall 1957. While she rejects “Cowboy Family”—a common term used on campus to describe all associated with OSU—as an identity group, her own family did speak of bleeding orange. She participated in her first efforts to change campus culture during protests following a 1990 decision by the OSU A&M Board of Regents limiting free speech on the Stillwater campus by canceling the showing of a movie, a decision she and other members of the Committee for the First Amendment considered to be based upon on the film’s perceived violation of Christian norms and traditions. Her involvement in Cowboys Coming Together, and this research, aligns closely with a deep and long-standing commitment to challenging and supporting students and others to develop civic skills. She extends challenge and support also to her alma mater, calling for and contributing to the institutional efforts to do and to be better vis-à-vis issues of free speech, campus climate, and addressing systemic inequities. In this way, she reflects the stated opinions of many members of the planning team and participants in the dialogues: CCT—the initiative itself and the individual organizers and planners—leans heavily into the space of change and, at the same time, holds itself in dynamic tension with the challenges that have lessened our ability to effect that change as quickly or as thoroughly as any one individual may hope.

Delimitations and Limitations

Cowboys Coming Together was originally a program responding to an immediate community need. As the program developed, the scope changed to intentionally include faculty and staff. Therefore, many of the survey methods used were designed to capture the original scope. Faculty and staff were not surveyed intentionally; instead, they were included among general participants.

Additionally, campus programming always requires adaptive measures to adjust for participant interest and attrition. Ideally, the social network survey would include a list of participants for each person to identify with whom they were familiar prior to the start of CCT. Participants would also be able to indicate their networks before and after the dialogue program. However, due to assignments happening very close to the start of the program, there was no social network survey administered prior to CCT. It was also not possible to produce a list of participants for individuals to select as part of their individual networks.

Due to the quick recruitment of participants at the beginning of the semester, the first cohort likely did not reflect the diversity of experiences at OSU. The recruitment process was conducted using actively engaged campus organizations which yielded participants who were also engaged. Particularly, ideological differences were not represented among the participants; that is, politically conservative individuals were largely not represented.

Finally, when measuring self-efficacy, the researchers found that participants were highly trusting and had high self-efficacy in participating in political and non-political engagement. These participants were likely more amenable to having conversations across differences. Therefore, it is difficult to measure whether, or the extent to which, participation in CCT changed those attitudes due to a recruitment ceiling effect.

Future Directions for Moving Dialogue to Change in Campus-as-Community Settings

Using social network analysis techniques, researchers have described CCT participants as individuals who not only trust others, but also have faith in their own ability to express themselves in conversations exploring diverse opinions on contentious subjects. No one reporting conservative political beliefs participated in the dialogues, and most individuals were already active in one or more organizations on campus. As a group, the participants did not represent the diversity of the OSU main campus-as-community. They likely did have something in common with people who are drawn to dialogue-based approaches to community problem solving in general; and OSU as a whole is typical of a large campus in a college town. Accordingly, the previous discussion offers reflection points for scholars and practitioners seeking to advance deliberative dialogues in the campus-as-community.

In Dialogue with Deliberative Democracy

The success of this dialogue to change program offers an opportunity to learn and develop more intentional dialogue programs in the future. Overwhelmingly, participants viewed their participation in CCT as a positive experience. Additionally, their participation increased their understanding of others’ attitudes and beliefs, and their ability to communicate with people who hold beliefs different from their own. Therefore, future dialogue programs can and should build on these strengths

A relatively large number (n = 42) of campus organizations were represented in the first round of CCT. The most prominent groups focused on student governance, fraternity and sorority life (especially historically Black fraternities and sororities), and campus organizations centering on racial/ethnic solidarity and justice issues. However, most CCT participants responded to the invitation to join the dialogues based on an individual decision they had already made to prioritize addressing racial issues on campus. While the dialogue to change process could engage greater viewpoints, the social network analysis revealed that racial/ethnic identity groups were connected within similar identities (e.g., NPHC fraternities and sororities), and cross-group connections were not present. CCT still has the opportunity to bridge the differences between and among the underrepresented identity groups on campus. This can occur by piloting affinity groups, which often focus on bringing together individuals of a particular identity to discuss a topic before coming together in a larger group. However, the network suggests there may be natural affinity groups based on membership in campus organizations. The Student Government Association could have an affinity group in this network, as could NPHC.

There were other areas of the campus-as-community from which CCT did not capture a diverse pool of participants. Students who were not already engaged on campus made up less than half of the participants in CCT. Additionally, most students who did engage were largely trusting and engaged civically prior to the program. Preparing for future CCT dialogues, it will be necessary to recruit participants who are unengaged in order to continue creating new social networks. Furthermore, recruiting students who are less trusting is important because this type of dialogue program can foster increased trust and confidence. In addition, political ideology was largely moderate to liberal, with only one participant identifying as conservative. Given the politicized nature of racial issues in the United States, a diversity of political ideologies is critical.

The unexpectedly strong participation by administrative staff members in CCT 1.0 and 2.0 suggests an opportunity to think more deeply about the role that professional staff play in the campus-as-community, particularly regarding organizational culture change and student success goals. Many of the staff had connections to multicultural groups and could therefore serve as effective bridges, connecting other students to resources. Because the participation of faculty and staff was unexpected, their experience was not surveyed differently than that of student participants. Therefore, there is an opportunity to study the faculty and staff networks as well as their ideological and attitudinal changes through programs such as CCT.

Finally, CCT can build on the strengths of the organizations represented. The SGA is the most central organization in the larger network, connecting the remaining most central organizations. Other central organizations, such as Alpha Phi Alpha and the National Pan-Hellenic Council, bridge organizations and should be included in the development of future CCT programming. Previous research and our experience with CCT at OSU have shown that dialogue programs hold promise in changing individuals’ understanding and attitudes about race and racial equity. However, there were many significant takeaways regarding the process and the evaluation that we used, and we will use that information to improve future iterations of the CCT program.

Recommendations

Because CCT was responding to an immediate need on campus, complete pre-dialogue data were not collected to compare to the post-dialogue results. In particular, understanding the network characteristics of both individuals and organizations before and after the dialogue would offer a better understanding of how the dialogues shape connections between individuals and groups.

The dialogue to change program does not occur in isolation. Therefore, incorporating a longitudinal component to examine the impact of participation in CCT on participants—and change in the campus-as-community—over time would be beneficial. In particular, understanding how participants utilize newly formed networks following the dialogues would help guide the development of future dialogue guides.

Finally, if future dialogue cycles recruit more participants who are hard to reach on campus and are not active or engaged in their community, these participants can be compared with more active participants. Understanding the scope of CCT to foster new behaviors of civic and/or political and non-political engagement (Jacoby, 2009; Saltmarsh & Zlotkowski, 2011), as well as campus leadership, would lend greater clarity to the additional outcomes of the dialogue program.

References

Abdullah, C. M., & McCormack, S. (2008). Facing racism in a diverse nation. The Paul J. Aicher Foundation.

American Historical Association. (1998). Why study history? (1998). https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/historical-archives/why-study-history-(1998)

Barnhardt, C. (2017). Challenges to diversity: Engaged administrative leadership for transformation in contested domains. In B. Overton, P. A. Pasque, & J. C. Burkhardt (Eds.), Engaged research and practice: Higher education and the pursuit of the public good (pp. 109–133). Stylus.

Battistoni, R., & Longo, N.V. (2011). Putting students at the center of civic engagement. In J. Saltmarsh & M. Hartley (Eds.), “To serve a larger purpose”: Engagement for democracy and the transformation of higher education (pp. 199–216). Temple University Press.

Borgatti, S. P., & Everett, M. G. (1997). Network analysis of 2-mode data. Social Networks, 19(3), 243–270.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2018). Analyzing social networks. Sage.

Britton, D. (2017, January 19). OSU students apologize for “thoughtless” Instagram post. Stillwater NewsPress. https://www.stwnewspress.com/news/osu-students-apologize-for-thoughtless-instagram-photo/article_b6185f0a-8eb4-5d26-a3c0-21dc9e6af34b.html

Britton, D. (2018, January 26). OSU president responds to Four Percent student group demands. Stillwater NewsPress. https://www.stwnewspress.com/news/osu-president-responds-to-four-percent-student-group-demands/article_4cfea084-02e4-11e8-bb9f-ff03568f6900.html#utm_campaign=blox&utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social

Browne-Marshall, G. J. (2007). Race, law, and American society: 1607 to present. Routledge.

Bryant, A. N., Gayles, J. G., & Davis, H. A. (2012). The relationship between civic behavior and civic values: A conceptual model. Research in Higher Education, 53, 76–93.

Cabrera, N. L. (2018). White guys on campus: Racism, white immunity, and the myth of “post-racial” higher education. Rutgers University Press.

Clark, B. R. (1972). The organizational saga in higher education. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(1), 178–184.

Colby, A., Beaumont, E., Ehrlich, T., & Corngold, J. (2010). Educating for democracy: Preparing undergraduates for responsible political engagement. John Wiley & Sons.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Davis, N. R. (2009, February 19). Interview by Jerry Gill [Video recording]. O-State Stories, Digital Collections @ OKSTATE Library.

DeLaet, D. (2015). A pedagogy of civic engagement for the undergraduate political science classroom. Journal of Political Science Education, 12(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2015.1063434

Dionne, E. J. (2012). Our divided political heart: The battle for the American idea in an age of discontent. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Dugan, J. P. (2017). Leadership theory: Cultivating critical perspectives. Jossey-Bass.

Fasching-Varner, K. J., Albert, K. A., Mitchel, R. W., & Allen, C. A. (Eds.). (2015). Racial battle fatigue in higher education: Exposing the myth of post-racial America. Rowman & Littlefield.

Fernandez, M., & Perez-Pena, R. (2015, March 10). As two Oklahoma students are expelled for racist chant, Sigma Alpha Epsilon vows wider inquiry. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/11/us/university-of-oklahoma-sigma-alpha-epsilon-racist-fraternity-video.html

Fiorina, M. P. (2013). America’s polarized politics: Causes and solutions. Perspectives on Politics, 11(3), 852-859. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9984/9068a5ed7c38019a43247c66254a39ef29eb.pdf

Fischer, K. (2019, February 17). “It’s a new assault on the university.” Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/its-a-new-assault-on-the-university/

Fredrickson, K. (2012, October 18). Without rules: The untold story of the Johnny Bright incident. Daily O’Collegian. http://www.ocolly.com/sports/football/without-rules-the-untold-story-of-the-johnny-bright-incident/article_1f5c49e2-198d-11e2-9689-001a4bcf6878.html

Galston, W. (2010). Why a hyper-polarized party system weakens America’s democracy. Hedgehog Review, 12(3), 57–60.

Gregory, D. (2018, January 18). OSU student who posted racist Snapchat issues apology. Daily O’Collegian. http://www.ocolly.com/news/osu-student-who-posted-racist-snapchat-issues-apology/article_df7c18e2-fc77-11e7-b5ea-0775a1c3fdb0.html.

Harper, S. R. (2013). Am I my brother’s teacher? Black undergraduates, racial socialization, and peer pedagogies in predominantly white postsecondary contexts. Review of Research in Education, 37(1), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X12471300