Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) poses significant risks to society in general and to higher education specifically. However, it offers potential benefits regarding students’ civic learning and democratic engagement. By equipping students with the skills to use AI for the common good and fostering their awareness of the potential dangers of AI, we can bolster democracy. In this article, we explore the status quo along with expectations and near-term predictions for AI. Next, we explore some of the most significant and common AI-related concerns. Finally, we draw upon a variety of resources, identify “best practices,” analyze the strengths and weaknesses of AI, and discuss class-tested teaching techniques to put forth an AI-based pedagogical approach that can maximize AI’s positive potential while side-stepping areas of concern.

We are living through exciting, thrilling, and challenging times. One of the crucial aspects of this unique, conjunctural moment is the rapidly expanding and ongoing development of artificial intelligence (AI). Not too long ago, our exposure to AI only occurred through Sci-Fi movies, television series, books, etc. However, now we are experiencing more “sci” than “fi” as the world notes the seemingly ever-presence of AI into our everyday lives. To be sure, we utilize AI when we ask Siri or Alexa for help, when we rely on AI chatbots to provide us quick answers with FAQs during online shopping, and when we love or hate it when Microsoft Word or Google searches anticipate our next words so they offer suggestions that can make our typing just a bit faster – or those AI-generated suggestions might expand our thinking and foment ideas for which we may not have been able to consider absent the assistance of AI.

Indeed, a major concern from some critics is that AI threatens to replace certain jobs, which could then trigger higher rates of unemployment, greater strains on social welfare programs, and a significant threat to the workers’ confidence who may be receiving their pink slip—from a robot. This also means that more and more jobs are incorporating AI into their business models. This, coupled with the intense speed at which AI “learning” is occurring, suggests that AI really is ubiquitous and expanding. One AI researcher notes how, at the current speed of development, in just two short years AI will be 100 times more powerful than it is today in AI-specific areas, and approximately 45 years in all other human-driven processes (Bragg, 2018). In addition, Kurzweil (2024) predicts that AI will master the language and commonsense reasoning possessed by humans by 2029.

These two elements – AI’s prevalence and its rapid proliferation of potency – congeal to reveal, at least in part, some reasons why AI is igniting massive amounts of research. We are eager to see how AI can potentially revolutionize higher education, but we also believe an incremental and cautious approach forward is prudent. Given our personal frameworks regarding AI, we will organize this essay into three main sections. First, by way of an introduction. We note the status quo along with expectations and near-term predictions for AI development are at-odds with measured and tempered implementation. Next, we explore some of the most significant and common concerns related to AI. Given some of the ways that AI reflects our larger culture, we will briefly discuss how – in general – AI presents a type of cultural precarity for which we must consciously be aware. We then concentrate on how AI can positively intersect with and influence pedagogy.

For many in higher education, AI is perceived as an exciting new paradigm in teaching and learning, while others view AI as a way to engage in legitimate shortcuts such that the instructor can use their time more efficiently instead of grading basic quizzes, organize lesson plans, craft discussion questions, etc. As a result, we examine how AI can yield significant benefits during the teaching process, while also reflexively problematizing potential AI-related drawbacks. Ultimately, we draw upon a variety of resources, identify “best practices,” analyze the strengths and weaknesses of AI, and discuss class-tested teaching techniques to put forth an AI-based pedagogical approach that can maximize AI’s positive potential while side- stepping areas of concern.

Exploring AI: A Holistic Overview

We will focus on AI’s potential impact on teaching, but we think it is important to contextualize AI as a teaching tool within a larger social and cultural context. For example, while AI promises mechanisms that will ease and broaden our lives, there are also potential risks that could be devastating. If successful and effective AI is to emerge, we need to wrestle with some of AI’s disadvantages. As we shall explore, any responsible, meaningful, and effective development of AI must confront the basic connection between AI and its potential connection to various, problematical catastrophes.

Although the fundamental processing and activity of artificial intelligence has existed for a couple of decades, it wasn’t until November of 2022, when ChatGPT debuted its processing as a Large Language Model (LLM), which allowed everyday citizens to utilize OpenAI that catapulted the mysterious, exciting, and user-friendly AI (Kreps & Kriner, 2023). The immediate buzz about AI quickly spread throughout society. People from varied and diverse industries (e.g., construction managers to professors, medical doctors to trucking logistics, medical coding to HR trainers) are conversing more and more about the nature and impact of AI on their lives. Since AI is a constant “work in progress,” there is no firm start date regarding its inception, and we continue to utilize AI, particularly in ways that fit our teaching and research. And, almost immediately, academics aligned themselves with one of the following camps: 1) researchers fascinated and excited about the hype and prospects of teaching AI, 2) teachers who are ambivalent to incorporating AI into the classroom, 3) instructors who feel overwhelmed and overworked such that they hope AI will save them time and/or make their teaching easier, and 4) academics who view AI from a critical perspective, arguing, in part, that at a minimum AI does not deliver what it promises and, at worst, AI can prompt the end of humanity. With the last group, some scholars are divided along the notion of banning the use of AI in the classroom entirely versus those who seek a compromised, balanced incorporation of AI with other pedagogical techniques.

AI Precarity: Noting Possible Predicaments

We have all seen or at least heard, in pop culture television shows and movies, about the dystopian nightmares following the insertion of AI into humanity. In the Terminator movie franchise, the fictional AI-producing company Skynet becomes overrun by sentient AI who fear humans will exterminate them (Cameron, 1984). Similarly, AI-based Cylons in Battlestar Galactica fear for their survival from humans and seek retribution for when pre-sentient Cylons were used as forced labor by humans (Moore, 2004-2009). Hence, by simply mentioning these two examples among hundreds, anxiety, suspicion, and distrust of AI has become engrained into our cultural mythology.

However, today we are not facing fictional terminators or Cylons. Sentient AI is not yet a reality (at least in an open, large-scale way), but the increasing use and prevalence of AI is sparking worry and encouraging cynics all over the planet. Additionally, many leading and senior research scientists who formerly worked for AI-production companies – such as OpenAI, Google, and Element AI – are now going on record to alert humanity of the very real and serious risks that AI could provoke (Lovely, 2024). For instance, “Geoffrey Hinton, … the most cited living scientist, made waves … when he resigned from his senior role at Google to more freely sound off about the possibility that future AI systems could wipe out humanity” (Lovely, 2024, p. 67-68). Indeed, a group of brilliant scientists who have been instrumental in the development of AI have formed what they call the “X Risk Community,” who’s main goal is to generate awareness about the risks and disadvantages associated with AI, including the fear that “AI poses an existential risk to humanity” (Lovely, 2024, p. 68). In fact, the X Risk Community has been warning us of the real danger posed by a “lone actor” who uses AI for nefarious reasons, such as collapsing the financial industry, sabotaging our energy grids, overcoming protective encryption technology, and even acquiring access to weapons of mass destruction (Lovely, 2024). If there is any risk at all of the “lone actor” scenario, we must be cautious in how we teach the construction and use of AI, even in the most benign classroom.

Since AI essentially can remove the “thinking” that goes into many jobs, including teaching, educators naturally worry about how we might assess AI benefits – almost instant research, the crafting and wording of essays, evaluating student work, etc. – with potential disadvantages, such as cheating, plagiarism, and AI dependency. The list of potential drawbacks of AI classroom/assignment use is lengthy, so we will discuss some of the more relevant and significant detriments.

Of general concern for education is the impact AI has on research. There is little debate about how AI can meticulously scrape the Internet to locate important information regarding the topic of one’s prompt. However, there is serious concern that it is precisely because AI uses data already available on the Web that such information could be inaccurate, disingenuous, and even damaging. Known as “hallucinations,” AI can locate seemingly useful and related information that is actually misleading or false, while the way it is characterized by AI is with a confident certainty (Lacy, 2024).

Online operatives who intentionally want to produce and spread disinformation can use AI to their advantage. When generating disinformation, AI can point culprits to cites that reinforce false information, and the AI platform can facilitate the savvy and persuasive construction of disinformation by supplementing brainstorming and idea generation. Additionally, AI algorithms will promote the spread of disinformation by targeting and accessing large datasets of online users (McNeil, 2024). We also know that AI can manufacture deepfakes, which maximize the persuasive power of disinformation by coupling it with faux images (Scott, 2024; Sweeney, 2024). Some of this work could have been done before AI’s rise in popularity, but AI systems now optimize the development of disinformation and massively accelerate its disbursement. Moreover, when users access chatbots, their electronic signatures are already embedded in the exchange, and the AI could then use chatbots to amplify disinformation campaigns (Lacy, 2024; O’Brien, 2023).

Given that AI can generate lists and concepts that relate to other concepts, instructors are naturally curious about how AI brainstorms ideas instead of author-generated ideas. For instance, if an author wants to know all of the different, yet relevant, concepts linked to the notion of space exploration, they could do some preliminary reading and then think carefully and thoroughly about areas tied to space exploration (e.g., the monetary costs, the required resources, proper training of astronauts, the length of time needed for development and the length of time required for the actual travel, possible benefits acquired through exploration, etc.). Undergoing this process allows the author to visualize the connections between these concepts, understand their utility related to the paper’s argument, prioritize more important ideas from the trivial, develop a depth of knowledge about the topic and issues, and so on (Torgeson, 2023). In contrast, an AI platform can generate this list in under 20 seconds, and perhaps offer ideas that went unnoticed by the author. The fundamental concern here, however, is that using AI removes a human’s cognitive process when generating or brainstorming ideas, a process that has utility separate from producing an essay.

In a related way, working with other humans during idea generation can foster human relationships, cultivate important face-to-face communication skills, and offer a way to see how concepts are related rather than simply knowing that they are connected (Weatherby, 2024). Similarly, relying on AI impedes the development of the author’s agency and voice (Erickson, 2024). Using AI instead of human-generated ideas can also promote the perception of inauthentic expressions.

Since AI can replace human thinking in certain circumstances, many worry that utilizing AI for content-rich assignments (e.g., research papers, detailed case studies, in-depth presentations, etc.) will not only inhibit student learning of content, but it can also undermine the attempts by educators to convince students about the relevance and salience of the course content (Hall & Zito, 2020). Furthermore, some researchers point to the way student “learning” has slowed and in some cases worsened when untested technology is used as a primary method of instruction, such as some Internet-based pedagogy, clickers, and so on (Weatherby, 2024). For these education specialists, AI is the latest technological fad that risks damaging productive learning in an intensified degree over past tech-based strategies. A related concern is that AI’s promise of thorough research abilities, advanced writing techniques, and incredible production speed will foster student dependency on AI (Bailey, 2023). If our students over-rely on tools like AI to the extent that they have difficulty learning and functioning without it, then foundational skills such as analytical and critical thinking, argument construction, the cultivation of creativity, and, to put it bluntly, nearly all worthwhile educational skills could realistically be eroded or lost completely (Hall & Zito, 2020; Sutton, 2024; Vos, 2023). Thus, “AI addiction” can become a serious problem.

Furthermore, and most importantly for many in higher education, AI language models are often touted as tools to address inequities and inequalities, especially for students with disabilities since AI-driven platforms can reinforce traditional teaching techniques with learning accommodations, such as special fonts, voice-to-text capabilities, close-captioning, predictive syntax functions, etc. Additionally, AI allows users to augment lessons for individualized instruction. Some scholars use a similar logic when emphasizing AI’s natural, human language proficiencies for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students (Douglas, 2024; Summers, 2024).

In addition to traditional language courses, AI can tailor language lessons to specific students’ needs. The promise of AI for EFL instruction is characterized by Douglas (2024) as “the integration of AI-driven chatbots represents a significant breakthrough, offering students immersive and interactive conversational practice” (p. 69). In another way, AI is also often portrayed as a democratizing tool that not only equalizes the playing (learning) field for underrepresented groups, but it also can identify weaknesses in course content and then offer a variety of possible techniques to rectify teaching inequities. In other words, many scholars argue that AI can target instructional areas that otherwise reinforce stereotypes, ignore, or tokenize material relating to marginalized groups, and other discriminatory practices, particularly for foreign language learners (Coffey, 2024).

Since the public launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT about two years ago, people from all over the world who work in a variety of industries were – and some still are – excited about the prospects of fairness, equity, inclusion, and counter-hegemonic potential from AI. Despite these ambitious aspirations, now that some of the hype and haze about the promises of AI have dissipated, we are now seeing some of the empirical instances where AI not only fails at deconstructing exploitative teaching practices, but AI can also actually perpetuate inequalities and damaging representations of various groups (Akselrod, 2021). AI generally reinforces social divisions in one of two ways. First, since most generative AI programs comb the Internet for data to answer a user’s prompt, the AI simply recycles and regurgitates the harmful information that already exists online (Crawford, 2021). Second, AI is, after all, an elaborate computer program that utilizes algorithms to capture relevant data sets. This means, of course, that the algorithms are developed by humans, and such programming can never be pure or neutral in that unconscious prejudices and bias will always be present (Akselrod, 2021; Noble, 2018).

Ongoing empirical documentation and study of AI’s role in exclusion, discrimination, and general inequalities exist in specific ways, such as racism (Akselrod, 2021; Crawford, 2021; Germain, 2023; Hsu, 2024), sexism (Milne, 2023; Newstead et al., 2023; Thomson & Thomas, 2023), and class inequity along with capitalist exploitation (Brudvig, 2022; Crawford, 2021; Lovely, 2024; Weatherby, 2024). Readers may ask, but what about simply programming algorithms to not be prejudiced? Because AI works based on its programming and the data it scours online, such prejudice-removal strategies still have a significant fail rate. For instance, in a study about racist tendencies in chatbots, Hsu (2024) notes,

Commercial AI chatbots demonstrate racial prejudice toward speakers of African American English – despite expressing superficially positive sentiments toward African Americans. This hidden bias could influence AI decisions about a person’s employability and criminality …. [a reputable study] discovered such covert prejudice in a dozen versions of large language models, including OpenAI’s GPT-4 and GPT-3.5, that power commercial chatbots already used by hundreds of millions of people. OpenAI did not respond to requests for comment. (para. 1-3)

Additionally, AI proponents may argue that such inequity and bias already exist. However, AI risks worsening divisive social relations when users view it as neutral, and the immense speed in how AI operates can amplify harmful messaging particularly when used in conjunction with the virality of social media.

While we might think that AI could be programmed to help sift through inaccuracies online, unfortunately that does not seem to happen, although theoretically we suppose it is possible. Instead, AI is typically used to magnify and accelerate disinformation, including the generation of deepfakes (Scott, 2024). We already discussed the problem of hallucinating, and when AI hallucinates, it can then be used to quickly disseminate false data all over the internet (McNeil, 2024). To make matters worse, AI can be programmed, and often is, to portray its message with a veneer of authenticity, even a display of confident accuracy. When this happens, unbeknownst human users are susceptible to believing it and sharing it with others (Lacy, 2024; O’Brien, 2023). As a corollary, this also means that when some users discover the disinformation stemming from AI, it can introduce distrust about the issue and certainly create feelings of suspicion and skepticism concerning media and information gathering in general (Sweeney, 2024).

For those of us interested in teaching democratic principles and values, the presence and future of AI paints a gloomy picture. Since 2024 is a presidential election year for the United States along with national elections in over 64 other countries this year, the potential impact of AI on information gathering as well as information manipulation is alarming (Ewe, 2023).

Because AI functions on human-created code, people can use it to manipulate candidate campaign messages, news headlines, and election-related websites (Panditharatne, 2024). As a result, we cannot emphasize enough the potential ramifications of AI-based disinformation relating to democratic elections: “In a year where billions will vote in elections around the world, the 2024 annual risk report warned that misinformation and disinformation ‘could seriously destabilize the real and perceived legitimacy of newly elected governments, risking political unrest,

violence and terrorism, and a longer-term erosion of democratic processes’” (Sweeney, 2024, para. 2-5).

AI can jeopardize democratic elections in several ways, but here are the four most likely: First, at the most basic level, AI will help spread disinformation. Notably, “AI’s ability to create deepfakes and spread disinformation, especially through social media platforms, can create false narratives, impersonate candidates, and manipulate public opinion” (Capitol Technology University, 2024). According to the same source, AI is already used in this manner, such as the deepfake of President Biden instructing New Hampshire voters to not vote in their primary election. A second way AI can damage elections is by actively interfering in them. AI can be programmed to infiltrate computerized processes, such as registration databases and electronic voting machines, along with messages implying that the integrity of the elections is in jeopardy, thereby eroding the trust citizens have in the process (Abrams, 2019; Capitol Technology University, 2024). As we saw in the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections, foreign actors – like Russia – can use disinformation to divide Americans and magnify the distrust many voters already have in the electoral process (Balani, 2022). As AI advances, so too does the risk of undermining our democratic framework. Dr. Kreps and Dr. Kriner, who both teach government at Cornell University, explain how this very possible threat might emerge:

The potential political applications are myriad. Recent research shows that AI-generated propaganda is just as believable as propaganda written by humans. This, combined with new capacities for microtargeting, could revolutionize disinformation campaigns, rendering them far more effective than the efforts to influence the 2016 election. A steady stream of targeted misinformation could skew how voters perceive the actions and performance of elected officials to such a degree that elections cease to provide a genuine mechanism of accountability since the premise of what people are voting on is itself factually dubious. (Kreps & Kriner, 2023, para. 14)

In a related way, AI can be used to saturate lawmakers with phony concerns, which will make it impossible for representatives to know what truthfully is troubling citizens (Kreps & Kriner, 2023). A final, common, problem that AI poses is when it is used by voters to ascertain appropriate, fair, and accurate information about candidates. AI can be programmed to attack genuine information by replacing it with disinformation, while simultaneously instructing voters to visit the wrong voting venues and other voting obstruction techniques (Capitol Technology University, 2024; Panditharatne, 2024).

We recognize and chart several potential problematic consequences of implementing AI. Our intent is not to be alarmists, but rather we underscore how using AI in the classroom can be both exhilarating and frustrating. Theoretically, AI can radically improve how we teach and learn, but it also risks serious impediments to learning or, worse still, AI can be used to spread disinformation and jeopardize our democratic institutions and processes.

We have already discussed the importance of educators engaging in careful consideration and conscientious self-reflexivity when implementing AI in the classroom. More specifically, teachers should include and stress digital literacy skills as one way of preempting some of the malicious uses of AI. We believe that Long and Magerko (2020) offer a useful, working definition of AI literacy: “a set of competencies that enables individuals to critically evaluate AI technologies; communicate and collaborate effectively with AI; and use AI as a tool online, at home, and in the workplace” (p. 2). It stands to reason, then, that there are several literacy techniques that can be discussed and adopted, but too many to be described here.

To begin the conversation with our students, we should introduce the four key areas where AI can influence knowledge acquisition: 1) text generation, where the AI produces actual texts of sentences and paragraphs in response to a specific prompt question; 2) image generation, which is when AI can yield an image based on characteristics and parameters that are outlined in the prompt; 3) audio generation, which is when AI can use “deep learning techniques” to reproduce certain sounds, including human voices; and 4) video generation, which, similar to the other generative functions, can use existing images or create some from scratch (Clark, 2023).

Furthermore, educators should examine these skills themselves to see what might work best for the subject matter they teach, the aptitudes of their students, and the specific contexts in which AI will be adopted. Some examples of literacy skills and related exercises might include role play, deliberative dialogue, mind mapping, storytelling, simulations, or case studies. However, as we have noted, many other literacy skills and programs exist, and instructors should carefully consider which ones will be the most effective given their specific circumstances.

For some students, digital literacy may require foundational knowledge, which they may lack if their high schools prioritized other paradigmatic areas, such as scientific, computational, or philosophical frameworks, or their schools may avoid teaching digital literacy altogether (Long & Magerko, 2020). Under-represented groups and low-income area public schools may experience severe economic inequities. Unfortunately, austerity programs and mismanaged budgeting forces some schools and teachers to triage some subjects and programs, which regrettably results in cutbacks or retiring pedagogy involving argument construction, deeper-level analytical skills, conversation and listening skills, and critical thinking skills (Hirsh, 2011). The foundational knowledge necessary for AI literacy should establish core competencies, such as an operational vocabulary of words and concepts along with a fundamental proficiency in AI utilization, a working understanding of how AI functions, and knowledge about, and practical experience with, critical thinking skills (Long & Magerko, 2020). Learning these skills with the requisite amount of knowledge is possible and occurs often.

However, for these competencies to be sufficient, learners must commit to an intensive program of skill acquisition. Of course, for some people this process will not occur overnight; instead, it can be a long, arduous journey such that knowledge and skills learned today are premised by a set of skills and knowledge before that, and so on. The acquisition of important knowledge and the development of thinking and communication skills will undoubtedly require a hefty time commitment and a serious approach to learning. However, in the end, by not teaching or emphasizing digital literacy skills, “we are essentially stifling their potential” (Long & Magerko, 2020). Instead, we should concentrate on how students and practitioners can learn these vital, life-long skills that are also crucial for the use of AI.

Utilizing AI in the Classroom: Tested Techniques

Despite the risks, several scholars have noted the potential benefits of AI in terms of bolstering civic engagement and democracy. For example, Abdulkareem (2024) argues that AI could increase access and understanding of government, especially for underserved groups. Savaget et al. (2019) claim that AI could empower more diffused forms of political participation extending far beyond electoral politics. Further, Meyer et al. (2022) argue that those in higher education should lead efforts to equip students with digital literacy skills, including how to use AI ethically, to ensure that these technologies contribute to the common good.

Social media analytics (SMA) offers educators one way to develop students’ digital literacy and civic engagement skills. SMA involves the analysis of big data “using a robust combination of mathematical applications, computer coding and programming, and data visualization to help us tell a more comprehensive story of what’s happening within this vast expanse of online information” (Mazer et al., 2025, p. 80). In the context of civic learning, students can use SMA to identify mis- and disinformation and political extremism (Meyer et al., 2022). It can also help students better understand the nature of online political communication.

At our university, we use a subscription-based social media listening platform called Talkwalker (see https://www.talkwalker.com) to empower students to make sense of data on the social web. More specifically, Talkwalker uses simple Boolean searches to provide real-time social media, web monitoring, and advanced analytics. The backbone of this platform is the proprietary Blue Silk AI technology. Blue Silk AI uses internal and external insights related to our searches to provide deep insights into the data. For example, Blue Silk can quickly content-analyze extremely large data sets to provide a useful overview of the data.

To give readers a better sense of how we use SMA, we conducted a search on Talkwalker on July 2, 2024, using the terms “presidential immunity.” The search returned 548,700 mentions of the key terms from June 3, 2024, to July 2, 2024. The conversation peaked on July 1, 2024, following the Supreme Court’s release of the decision in Trump v. United States (2024). To begin our analysis, we selected the peak of the conversation which included 293,400 mentions from midnight on July 1 through midnight on July 2. We analyzed the content of the posts in the peak using Blue Silk AI which revealed the following results:

- Presidential immunity and its implications: Most of the posts discuss the recent Supreme Court decision on presidential immunity, with some expressing concern about the potential consequences and others celebrating the ruling as a victory for the presidency.

- Political polarization: Many of the tweets reveal deep political divisions, with users from both sides of the aisle sharing their perspectives on the issue. Some posts use inflammatory language or make personal attacks, highlighting the current polarized state of American politics.

- Legal precedents and unofficial acts: There is a focus on the distinction between official and unofficial acts, with some users questioning how this aspect of the ruling will play out in future cases.

- Criticism of Trump and his administration: Several posts criticize former President Trump and his administration, often using strong language or making accusations of corruption or criminal behavior.

- Defense of Biden and the Democratic Party: Other tweets defend President Biden and the Democratic Party, sometimes attacking Republicans or accusing them of hypocrisy.

These highlights provided by AI-based Talkwalker show the key themes related to our search terms. They show the concerns of social media users about the implications of the decision for democracy and those celebrating the ruling. They also highlight how political polarization influences online political communication. Importantly, the AI returned these highlights virtually instantaneously. Before AI, manual coding of almost 300,000 posts would have taken days, even with a large team of coders.

We can also show students how to analyze the sentiment of the mentions in this peak. According to the sentiment engine in Talkwalker, 55.3% of the posts in the peak are positive, 40.8% are negative, and 3.9% are neutral. Importantly, this does not reflect sentiment toward the key terms, the decision, or former president Trump or President Biden. Instead, it reflects the fact that terms used in the posts matched terms listed in a sentiment library. For example, the following post by House Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi (2024) contains terms that were coded as negative:

Today, the Supreme Court has gone rogue with its decision, violating the foundational American principle that no one is above the law. The former president’s claim of total presidential immunity is an insult to the vision of our founders, who declared independence from a King. (Pelosi, 2024, 10:58 AM)

Using Blue Silk AI, we obtained the following highlights of the sentiment analysis:

- Presidential Immunity: All documents discuss the recent Supreme Court ruling regarding presidential immunity, with different perspectives from various Twitter users.

- Political Divide: The documents showcase a clear political divide among individuals, with some defending the ruling and others criticizing it.

- Lack of Understanding: Some tweets indicate a lack of understanding or disagreement with the legal terminology used in the ruling.

- Expansion of Executive Power: One document mentions the potential expansion of executive power due to the ruling.

We can use these insights to help students understand the affective nature of online communication about the ruling. Of course, the tenor of the conversation reflects how divisive our politics have become. Talkwalker also analyzes sentiment in relationship to how the post spreads through the social web. As we might imagine, the more emotional and negative posts spread faster than logical and positive posts. In class, we would emphasize how the social media prism contributes to extremism and threatens democracy. According to Bail (2021), while the social media prism “makes one’s own extremism seem reasonable—or even normal—it makes the other side seem more aggressive, extreme, and uncivil” (p. 67).

This sample search illustrates how students can use AI to advance their digital literacy and civic engagement skills. Over the last few semesters, we have used Talkwalker in partnership with our Center for Civic Engagement to monitor primary elections, helped graduate students identify conspiracy theories in a health communication class, and taught undergraduate students to use the platform to explore persuasion strategies on a variety of political topics.

It is important to note that there are a wide variety of third-party vendors that provide access to social media analytics. Some of these services are free and others range in cost from a few dollars to thousands of dollars per month. For a list of such services, including free applications, see Mazer et al. (2025) and Meyer et al. (2022). Beyond the issue of cost, it is also important to acknowledge that social media platforms often contain skewed user demographics that are not representative of the public. As a result, analyses of social media data may fail to reveal the full conversation on the topic or perpetuate bias by excluding certain groups of people. To minimize this problem, we suggest that researchers use multiple data sources and acknowledge the limitations of this methodology in any data they share.

“Good” Pedagogy Offers a Path through the AI Minefield

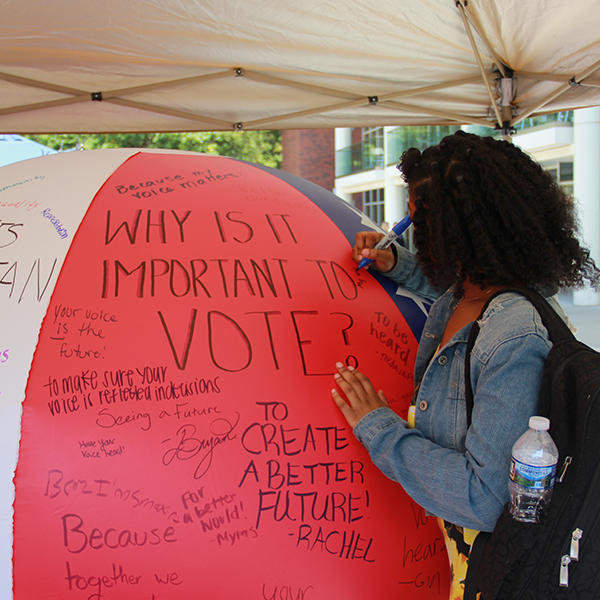

Incorporating new media and technology into the classroom has happened many times prior to this conversation. New gadgets and ideas have come and remained or gone all the while hindering or propelling pedagogical progression. Some are not always embraced unanimously by educators. The advantageous and disadvantageous learning outcomes usually depended upon user adaptation toward existing problems or innovative application for new directions. Granted, artificial intelligence technology is a game changer that will require a new level of adaptation and sensitivity by educators, instructors, learners, and administrators magnifying the necessity for effective civic education. Many scholars, researchers, and educators (Erhlich, 2000; Jacoby, 2009; Stamm, 2009) believe that one of the goals of higher education is to prepare students to become contributing citizens and to be able to deal with local and global complexities of modern societies as well as civic processes and practices.

Education is where students can learn to counter unscrupulous attacks on democracy while also confounding mistruths. Gallagher (2021) shouts that higher education needs to empower students to become active citizens. “In such circumstances, the drive to defend democratic culture becomes even more important, not to promote particularistic political positions but to defend and underpin the democratic process itself. In this crisis of democracy, it is an imperative for higher education to play its role” (para. 19). AI, like most new technologies and media, will play a crucial role in civic education classrooms. The Nashman Center Faculty Update (2024) refers to a report from CivXNow (2024), an educational coalition, which “outlines potential positive and negative effects of AI on civic knowledge, skills, dispositions, and behaviors. For example, AI could provide engaging historical simulations, but also distort events and spread misinformation. The authors argue educators must intentionally shape AI’s development and use it to support rather than undermine democratic aims” (para. 3).

With technological advancements and globalization, civic education is becoming more complicated. Zhang (2022) calls for educators to be calculated as they blend AI and civic education relying on civic values and being watchful of “civic hazards that AI technology may bring to the human society” (sect. 2, para. 3),” however, there still is hesitancy among some teachers. Langreo (2024), based on a survey from K-12 classrooms, claims that 37% of teachers said they would never use AI or plan to start, while 29 % of teachers indicated they have not accessed AI but plan to start. The numbers might be different for college instructors, but they are revealing, nonetheless. Zhang (2022) suggests the need for “the development of competencies for active participation in, including critical understandings and deliberations of the complexities inherent in exercising the right and responsibilities of community life” (sect. 3). In this way, AI presents a major challenge for civic education requiring educators to implement a “deliberative framework…based on the deliberative ideal of citizenship” (sect. 3).

As mentioned earlier, there are many potential problematic and insidious outcomes due to the rapid evolution of AI. Regardless of the game changing possibilities with AI, the various stakeholders will still need to ascertain a way to keep pace with the virtual escalation and determine how to lead the way rather than be led by AI. Nantaburom (2023) says the emergence of AI technology is very similar to the emergence of computers and the internet, which educators were able to embrace and optimize for the betterment of students and society in general.

Nantaburom continues: “To illustrate, ChatGPT is a very significant AI that exposes the potential in working and learning for whoever can use it… This transforms the way of learning to the higher order of all thinking, affection, and behavior to use intelligence tools to achieve the goal of learning” (p. 122). The alignment of curriculum, pedagogy, and educational policy should include AI literacy for beneficial outcomes. Because of the prevalence and potential pitfalls of AI, educational stakeholders will constantly need to contemplate and implement proactive ways to adapt to AI, as well as engage in meaningful self-reflection during the implementation of AI. Other sectors influenced by AI could provide some clues.

The Learning and Development or Training Industry has already passed the AI curve, offering multiple virtual and classroom-based training opportunities for practitioners and HR professionals about how to incorporate AI content into the training process. Additionally, the Training Industry shows how to use AI to enhance Instructional Systematic Design strategies, which potentially will hasten the iterative aspect for generating advanced performance outcomes without completely losing the human aspect of learning development (Brandon; 2023).

There are several examples of using AI effectively in the workplace: This includes combining AI with PowerPoint to create visually appealing presentations, employing AI to provide immediate feedback for quicker growth opportunities, offering case studies and simulations to improve critical thinking and problem solving, using AI to augment workplace scenario stories, and using AI to calculate real-time assessment of field work and collected data to speed up communication with the client (Bhaduri, 2024; DaCosta & Kinsell, 2024). This work offers a litmus test for educational practitioners. Even with all of this, the challenge for training professionals, along with educators, is to be reactive and responsive to unforeseen adaptations by AI and user innovations. The challenge for educators will be how to anticipate stakeholder expectations while making learner-centered needs the dominant drivers of process and content adjustment, especially in civic education.

Professional development for instructors needs to focus on integrating AI into civic learning processes. This should involve real-life challenges across disciplines and grade levels with relevant strategies that encompass age and rigor. How to teach civic education, rather than only dealing with how to access AI, should be the priority. With all the pitfalls and potholes that tend to dominate the headlines, educators need to discover ways to co-exist with the surges in technological opportunities. Upon overcoming the initial urge to portray students who use AI as potential cheaters or the perception that other students are left behind, educators must work to become informed, intentional developers of the practical application of AI and be at the forefront of the technological wave as much as possible. With proper preparation, instructors will be able to discover new ways of augmenting traditional approaches with the assistance of AI, in the effort to improve student participation, immersion, and experiential learning related to civic, political, governmental, and historical education.

Nantaburom (2023) urges educators to instruct with careful, meaningful, and responsible techniques because, “balancing technological advancements with human expertise is crucial, as AI should complement, not replace, human teaching” (para.2). The goal is not to replace other ways of teaching and learning but to find ways to integrate AI into existing learning spaces and pedagogy, creating heightened civic agency for students, which allows them to be active participants in the learning process.

Instructors would be well-advised to design and blend intentional pedagogical strategies by carefully understanding and utilizing the students’ familiarity with AI. They would also benefit from recognizing the ever-increasing potential of AI coupled with their own teaching skills and breadth of knowledge. Some challenges for teachers to consider that come from barriers, limitations, or misperceptions of using AI include dealing with individual ethics, social norms, institutional policies, students’ attitudes, loss of human involvement, traditional student-teacher relationships, lack of shared strategies, lack of transparency, privacy, over reliance on AI for teaching, over reliance on AI as a means for advancing research, resistance to change, lack of self-confidence, equitable access to technology, available training opportunities, lack of resources, information literacy, uninformed choices for specific applications, and lack of institutional coordination. Westheimer et al. (2017) submit that stakeholders need to consider their particular situation prior to civic education because economic inequality prompts unfavorable social outcomes and erects barriers to educational access and successful learning. The lack of political voice, disproportionally shared resources, and educational reform often compromises outcomes in K-16 education as they shift from preparing active and engaged public citizens in favor of more career-oriented goals. Consequently, much of the content examining civic responsibilities and engagement has been limited, creating a “demographic divide,” which “results in unequal distribution of opportunities to practice democratic engagement.” This carries over into the classroom “to the extent that robust civic education opportunities are provided, increasing economic inequality has resulted in educational opportunity that is itself inequitably distributed” (Westheimer et al. 2017, p. 1046). Civic educators need to find ways to remedy the scarcity of civic education and disproportioned access. Diana Owen (2024) from the Civic Education Research Lab at Georgetown University, clarifies the challenge:

The role of preparing students to be digital citizens increasingly is shouldered by civic educators. Yet integrating digital technology in the classroom remains challenging for teachers and school administrators. Restricted resources, lack of professional development opportunities, limited instructional time for civics, and uncertain outcomes can hinder instructors from integrating digital media into their classes. The increasing prevalence of AI and the rise of natural language processing tools like ChatGPT have heightened the challenges. (para. 2)

With AI, civic educators also need to be a part of institutional and governmental policy creation, which develops and shares realistic AI applications. As such, teachers will need to generate inclusive and legitimate learning outcomes, finding ways to not lose foundational skills such as problem solving, critical thinking competencies, and innovation. Ultimately, the responsibility lies with teachers to demonstrate to students how we can ethically and correctly use this new technology for learning and citizenship.

Once instructors recognize individual, societal, and institutional barriers, they will be able to develop new strategies for implementing AI in the classroom to increase student engagement and additional, deeper learning opportunities (Srivastava, 2024). This can occur by figuring out how to 1) adapt to student learning styles as well as their mental wellness, 2) make the most of available resources, 3) reflectively recognize instructor teaching tendencies, tolerance, and knowledge, 4) acclimate to class and cohort sizes, 5) determine congruent delivery channels relevant to students’ learning styles, 6) manage diverse pedagogical tools, 5) better understand institutional policies and limitations, 6) continue to be intellectually curious, 7) advocate for institutional support and professional development, 8) recognize inclusive, equitable, and accessible course content as well as opportunities representative of social demographics, identifying biases, 9) maintain some degree of human involvement and relational presence in students’ lives, 10) not completely rely on AI to do the work, 11) continue to have conversations with students, colleagues, and administrators, 12) start with specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely (SMART) learning outcomes prior to incorporating AI, 13) sustain transparency, 14) ensure privacy and data security (Teachflow, 2023, para. 51), 15) monitor ethical, fair-minded behavior, 16) be accountable, 17) select appropriate AI platforms, and 18) recognize that what constitutes good pedagogy, regardless of the presence or absence of technology.

More articles about using AI are starting to appear. Nuñes (2024) captures much of the same sentiment as stated above when they highlight six ways to use AI as a teacher’s personal assistant generating outcomes such as personalization, supplementing tasks, and generating new activities. Content creators like those at Brock University (2024) set up a list of AI tools for teachers that will assist the learning process. Instances like this provide some hope that universities can effectively integrate AI into their curricula without sacrificing instruction of other important skills. The bloggers at Teachflow (2023) instruct us that, “By proactively addressing these challenges, we can ensure that AI-driven civic education remains equitable, unbiased, and beneficial for all students” (para. 31). AI will not make a teacher any better or worse solely by using it. Teachers need to beware of falling prey to the quick fix, monitor their own biases and tendencies, and embrace their own teaching weaknesses and strengths. AI can either exploit weaknesses or heighten strengths. Simply agreeing on what content to teach does not guarantee educators will always agree on how to teach components of civic engagement.

Teachflow (2023) also offers practical insights and resources that enrich good pedagogy with AI in their educational blog for teachers. For example, they suggest enlisting AI as a tool in civic education for such applications as community role-plays and a governmental simulation would involve “virtual environments that replicate real world political systems, allowing students to take on different roles and engage in simulated political activities … it allows students to apply their knowledge, develop critical thinking skills, and gain a practical understanding of the political processes that shape our societies” (para. 3).

Partnering with community organizations and experts as well as international collaborations can also create “transformative learning experiences” providing students with heightened civic agency. Along with the application of Social Media Analytics (SMA) as mentioned above, along with better student immersion in realistic role-plays and simulations, other approaches for employing AI to expand experiential learning could include such assorted tools as case studies, narratives, historical recreations, and virtual guest speakers with current and historical experts. When applying AI or any technology or media, instructors need to be prepared, familiar with the technology, observant, and guided by predetermined learning outcomes. As we discussed earlier, using AI can be a precarious situation for instructors. When using AI-inspired content and pedagogy, instructors should not let AI be the primary method of instruction, inhibit student learning, undermine “relevance and salience of course content” (Hall & Zito, 2020), supplant face-to-face communication skills or lesson human relationships, paralyze human contributions or limit student agency, limit the cultivation of student innovation, lose the ability to differentiate between AI and human generated ideas, and lesson the rigor of learning.

Besides applying AI to generate teaching ideas, AI can also help modify teachers’ time commitments by making things more efficient with quicker performance feedback, lesson plan creation, personalized and self-paced lesson plans, and customized content, allowing more time for pursuits like student interaction, professional development, or new content development.

Leonard (2023) understands why teachers might be a little resistant to requiring students engage with AI tools. “Many AI platforms simply output a response with no information as to how they got there” (para. 1). In Edutopia, tech expert Davis (2023) stresses the need to respect the process and not just the solution. “Students don’t need an answer, they need help with the process” (para. 1). Critical-thinking assignments and activities utilizing AI could afford students new processes to interact with current and futuristic challenges or solving problems by engaging the past. Imagine having a conversation with President Lincoln about today’s “house divided,” talking with the campaign manager of Shirley Chisholm, who was the first African American woman to serve in Congress about her historic congressional campaign in 1969 or standing on the beach head of Normandy prior to the invasion, wondering how soldiers. Teachflow (2023) offers AI-powered, pedagogical strategies for the civic education classroom to enhance learning experiences related to civic and political engagement. Below are examples of simulations and role play exercises from Teachflow that let students experience civic processes in realistic and immersive environments.

AI algorithms play a crucial role in simulating governments by enabling realistic decision-making processes. These algorithms can model the behavior of various stakeholders, simulate the impact of different policies, and generate dynamic scenarios that reflect the complexities of real-world governance. Students can assume roles as government officials, analyze data, and make informed decisions based on AI-generated insights. The use of AI in decision-making simulations allows students to experience the challenges faced by policymakers, such as balancing competing interests, managing limited resources, and assessing the long-term consequences of their choices. Role-playing and simulation exercises are widely used in civic education to foster experiential learning. AI technology enhances these exercises by providing intelligent feedback, adaptive scenarios, and personalized learning paths. Students can take on different roles, such as elected officials, activists, or journalists, and engage in simulated political activities. (2023, sect. 1.3) This should not replace actual visits to governmental offices, internships, or shadowing, but simulations are the next best way for students to experience these spaces and get to participate in decision making and problem solving.

Here is an example from a leadership communication class: the big semester project is a typical research review paper. Realizing that students might already be tapping into various AI platforms for input with their homework, direct the students to submit a second paper along with their non-AI paper. That paper needs to be written with ChatGPT. Have the students create AI prompts from the project rubric and assessment sheet, so the AI input will mirror the actual paper instructions. The teacher will give feedback on the prompts to capture some fidelity to the original paper. Have the students submit both papers along with their AI prompts. At that point, distribute the pair of papers to alternative students and have them evaluate the writing, compare papers, and give feedback on pre-created evaluation sheet. After that, allow class time for the students to pair and share feedback. This, along with instructor feedback and peer discussion, will make the writing and comparative analysis of the two products a learnable moment for students.

This assignment could align with several learning outcomes including demonstrating an expertise with a set of knowledge and concepts, evaluating, and reviewing a particular body of literature, analyzing current research and applied trends as well as gaps, demonstrating information literacy, as well as being able to articulate a constructive critique. With this assignment, students will become better writers and witness firsthand how to have responsible and ethical interactions with AI. A class debriefing follows the assignment and can bring up key issues such as credible sources, truthful content, ethical considerations, and human perspective to the forefront. Also, instructors could offer real-time, formative performance evaluation and feedback making learning more iterative for students. Instructor modelling and being authentic will help students be able to ascertain best practices and make informed choices with clarity.

CivXNow (2023), a cross-partisan nonprofit coalition, administers projects that foster civic knowledge, skills, dispositions, and behaviors implemented in learning that can have both positive and negative effects. For example, when studying history, a simulation could provide multiple opportunities for students to engage in deeper, more digestible learning of historical events and fuller comprehension of history informing present issues. AI will open the door to large amounts of information challenging teachers to keep track of “content drift” depending upon the algorithm that drives the data set which could alter generated content over time. If not appropriately managed by teachers, the activity could create a negative effect by distorting historical events, expanding misinformation, reinforcing stereotypes, or misrepresentation of historical facts. The valence of the outcomes depends upon the pedagogical preparedness of the instructor.

Whether learning is asynchronous, self-paced, or classroom-based, AI can contribute to the formation of course structure and content. At the programmatic level, AI can assist in identifying new curricular directions and courses along with guiding policy to better align with students’ prospects as well as forthcoming civic options. The goal is not ignorantly to perpetuate or effortlessly repeat inherent cultural biases within content from questionable sources accessed by AI but to learn how to find, verify, and implement legitimate sources of credible information.

It is necessary, now more than ever due to the fluid landscape and inescapable nature of this virtual world, for educators to teach students how ethically to use AI in a responsible and appropriate manner for problem solving and futuristic evolutions within shared community spaces that adhere to policies, laws, and copyright or trademark regulations. On the “EdgeSurge” podcast, host Jeffrey Young (2024) talks with Zachary Cote, the executive director of the educational nonprofit, “Thinking Nation.” Cote plans to “leverage” AI as a tool to broaden the prominence of civic education and improve critical thinking skills such that we can become “effective citizens in our democracy.” On the same podcast, Rachel Dawson Humphries (2024), senior director of civic learning initiatives at the Bill of Rights Institute, suggests that AI could move students beyond just learning a set of facts, into an “opportunity to practice the skills of negotiation, the skills of engagement, the skills of give-and-take that happens in conversation” (para. 5).

As citizens and educators, teachers need to gain the knowledge and acquire the skills necessary for the practical application of AI in the classroom. The U.S. Department of Education (2023) advocates that teachers stay pivotal when incorporating and adopting AI. Their report “describes opportunities for using AI to improve education, recognize challenges that will arise, and develop recommendations to guide further policy development” (p.1). Before engaging AI for civic education, it will be helpful for instructors themselves to be civic minded, ethical practitioners, and culturally sensitive to optimally coach, model, and prepare students to utilize AI into their personal and professional lives fostering a deeper understanding to solving problems, making informed decisions, and being critical thinkers in complex situations.

Practitioners and scholars are not saying to abandon all traditional approaches and completely surrender to AI, but rather how can we best create and implement AI proactively and ethically. The work of teachers with civic education is about trying to find some type of professional equilibrium that will allow for progressive attitudes and practical considerations for using AI. Grounded in Lu’s (2024) civic education model based on artificial intelligence technology, they declare that this could work.

The new model shows a significant advantage in the interaction between the teacher and the students, the adaptability of personalized teaching content, and the accurate identification of student behaviors. The new model has significant advantages in interactions between teachers and students, personalized teaching content adaptability, and accurate identification of students’ behavior. This study shows that the Civic Education model and artificial intelligence technology can be an effective teaching reform method that can promote the complete development of students and innovation in Civic Education. (p. 20)

For AI to be beneficial and expedient, pedagogical strategies need to be laced with teachers’ own experiences, cultural sensitivities, and expertise. As teachers integrate AI into the classroom, they need to help students better understand the stumbling blocks and possibilities, so they can responsibly and ethically use AI in the workplace, civic organizations, and their political environment. AI technology is no replacement for educators’ own instincts, knowledge, or capabilities, but these technological advances can fundamentally alter how they do their work and assist students to become civically engaged. This evolution is happening, but as with other technological innovations, teachers need to evolve also, unless, of course, it turns out that AI is sending us cyborg terminators from the future. And, if educators get stuck, we can always ask AI.

Conclusion

In this essay, we have tried to grapple with the novelty and acceleration of AI as it pertains to an academic classroom. After understanding the context of AI’s development, we begin with the uneasy premise that AI poses significant risks to society and to education in particular. With those caveats in mind, we shared some practical ways of integrating AI into some of the courses we teach. Along those lines, we conclude that AI offers potential opportunities, if we do not veer off course. We must also use AI within a framework constructed and maintained by critical thinking, listening, and questioning. Through a process of self-reflexivity, whereby we guide and encourage the ethical use of AI in specific course exercises, we believe we can simultaneously integrate AI into our classrooms along with the care and caution necessary to avoid AI dependency and digital illiteracy, both of which will require direct and conscientious attention to minimize their likelihood and impact.

By equipping students with the skills to use AI for the common good and fostering their awareness of its potential dangers, we can bolster democracy. Ultimately, we agree with Kreps and Kriner (2023) that with “proper awareness of the potential risks and the guardrails to mitigate against their adverse effects, however, we can preserve and perhaps even strengthen democratic societies” (p. 129).

References

Abdulkareem, A. K. (2024). E-government in Nigeria: Can generative AI serve as a tool for civic engagement? Public Governance, Administration and Finances Law Review, 9(1), 75-90. https://doi.org/10.53116/pgaflr.7068

Abrams, A. (2019, April 18). Here’s what we know so far about Russia’s 2016 meddling. Time. https://time.com/5565991/russia-influence-2016-election/

Akselrod, O. (2021, July 13). How artificial intelligence can deepen racial and economic inequities. ACLU News. https://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/how-artificial- intelligence-can-deepen-racial-and-economic-inequities

Bail, C. (2021). Breaking the social media prism: How to make our platforms less polarizing. Princeton University Press.

Bailey, J. (2023, fall). AI in education. Education Next, 23(4). https://www.educationnext.org/a-i-in-education-leap-into-new-era-machine-intelligence-carries-risks-challenges-promises/

Balani, S. (2022, June 14). How Russia’s use of reflexive control can drive an opponent to the point of paralysis. The Prop Watch Project. https://www.propwatch.org/article.php?id=319

Bragg, T. (2018, May 31). Man v. machine: When will AI exceed human performance. TechHQ. https://techhq.com/2018/05/man-v-machine-when-will-ai-exceed-human-performance/

Brock University (2024). Guidance on generative AI. Centre for Pedagogical Innovation. https://brocku.ca/pedagogical-innovation/resources/guidance-on-chatgpt-and-generative- ai/

Brudvig, I. (2022). Feminist cities and AI. In A. Brandusescu & J. Reia (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in the city: Building civic engagement and public trust (pp. 28-29). Centre for Interdisciplinary Research of Montreal, McGill University. https://www.mcgill.ca/centre-montreal/projects/completed-projects/ai-city

Cameron, J. (Director). (1984). The Terminator [Film]. Orion Pictures.

Capitol Technology University (2024, May 14). The good, the bad, and the unknown: AI’s impact on the 2024 Presidential Election. https://www.captechu.edu/blog/good-bad-and- unknown-ais-impact-2024-presidential-election

CivXNow (2023). Resources. CivXNow: A Project of iCivics. https://civxnow.org/resource/all- resources/

Coffey, L. (2024, June 6). Lost in translation? AI adds hope and concern to language learning.

Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/artificial- intelligence/2024/06/06/ai-adds-hope-and-concern-foreign-language

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI. Yale University Press.

Davis, V. (2023). Using AI to Encourage Productive Struggle in Math. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-ai-encourage-productive-struggle-math-chatgpt-wolfram-alpha

Douglas, A. (2024). The AI powered classroom: A practical guide to enhancing teaching and learning with artificial intelligence. Graffham Consulting, Ltd.

Ehrlich, T. (2000). Civic responsibility and higher education. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Erickson, M. (2024, January 22). Rise of the AI schoolteacher. Jacobin, 52, 117. 20.https://jacobin.com/2024/01/rise-of-the-ai-schoolteacher

Ewe, K. (2023, December 28). The ultimate election year: All the elections around the world in 2024. Time. https://time.com/6550920/world-elections-2024/

Gallagher, T. (Spring, 2024). Democratic imperative for higher education: Empowering students to become active citizens. Liberal Education (AAC&U). https://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/articles/the-democratic-imperative-for-higher-education

Germain, T. (2023, April 13). ‘They’re all so dirty and smelly:’ Study unlocks ChatGPT’s inner racist. Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/chatgpt-ai-openai-study-frees-chat-gpt-inner-racist- 1850333646

Hall, E. & Zito, A. (2020). Locally sourced: Writing across the curriculum sourcebook. University of Wisconsin. https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/wacsourcebook/

Hirsh, S. (2011, March 28). Good teaching cannot fall victim to budget cuts. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-good-teaching-cannot-fall-victim-to-budget- cuts/2011/03

Hsu, J. (2024, March 7). AI chatbots use racist stereotypes even after anti-racism training. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2421067-ai-chatbots-use-racist- stereotypes-even-after-anti-racism-training/

Humphries, R. D. (2024, April 12). BRI talks AI in social studies classrooms. The Bill of Rights Institute. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/blog/bri-talks-ai-in-social-studies-classrooms

Jacoby, B. (2009). Civic engagement in higher education: Concepts and practices. Jossey Bass Publishing.

Kreps, S., & Kriner, D. (2023). How AI threatens democracy. Journal of Democracy, 34(4), 22-131. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2023.a907693

Kurzweil, R. (2024). The singularity is nearer: When we merge with AI. Viking.

Lacy, L. (2024, April 1). Hallucinations: Why AI makes stuff up, and what’s being done about it. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/tech/hallucinations-why-ai-makes-stuff-up-and-whats- being-done-about-it/

Langreo, L. (2024, January 8). Most teachers are not using AI: Here’s why. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/technology/most-teachers-are-not-using-ai-heres-why/2024/01

Leonard, D. (2023). 9 Tips for using AI for learning. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-ai-for-learning-fun/

Long, D. & B. Magerko (2020, April). What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-16). https://aiunplugged.lmc.gatech.edu/wp- content/uploads/sites/36/2020/08/CHI-2020-AI-Literacy-Paper-Camera-Ready.pdf

Lovely, G. (2024). Can humanity survive AI? Jacobin, 52, 66-79. https://jacobin.com/2024/01/can-humanity-survive-ai

Lu, Y. (2024). Practical innovation of students’ civic education model based on artificial intelligence technology. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, 9(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.2478/amns-2024-0827

Lynch, M. (2018). My vision for the future of artificial intelligence in education. The Edvocate. My Vision for the Future of Artificial Intelligence in Education – The Edvocate (theedadvocate.org)

Mazer, J. P., Boatwright, B. C., & Carpenter, N. J. (2025). Social media research methods. Cognella.

McNeil, T. (2024, February 26). Q&A: How misinformation and disinformation spread, the role of AI, and how we can guard against them. Phys.org. https://www.msn.com/en- us/news/technology/q-a-how-misinformation-and-disinformation-spread-the-role-of-ai- and-how-we-can-guard-against-them/ar-BB1iV9Am?ocid=winp1taskbar&cvid=38cf6f29841448d29a2028b09ad1fec0&ei=14

Meyer, K. R., Carpenter, N. J., & Hunt, S. K. (2022). Promoting critical reasoning: Civic engagement in an era of divisive politics and civil unrest. eJournal of Public Affairs, 2(1), 89-104. https://www.ejournalofpublicaffairs.org/promoting-critical-reasoning-civic-engagement-in-an-era-of-divisive-politics-and-civil-unrest/

Milne, S. (2023, November 29). AI image generator stable diffusion perpetuates racial and gendered stereotypes, study finds. University of Washington News. https://www.washington.edu/news/2023/11/29/ai-image-generator-stable-diffusion- perpetuates-racial-and-gendered-stereotypes-bias/

Moore, R. D. [Executive Producer]. (2004-2009). Battlestar Galactica [TV series]. Universal Television.

Nantaburom, S. (2023). AI and big data: Opportunities and challenges for civic education. 2023 International Conference Proceedings on the Citizenship Education of the Digital Era, 113-129.

Nashman Center for Civic Engagement and Public Service Faculty Update. New report: AI’s impact on civic education and democracy. George Washington University. New Report: AI’s Impact on Civic Education and Democracy (gwu.edu)

Newstead, T., Eager, B., & Wilson, S. (2023). How AI can perpetuate—or help mitigate— gender bias in leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 52(4), 100998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2023.100998

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt9w5

Nuñes, K. L. (2024). 6 ways to use AI as your personal teaching assistant. Bridge Universe. https://bridge.edu/tefl/blog/ways-teachers-can-use-artificial-intelligence/

O’Brien, M. (2023, August 1.) Chatbots sometimes make things up. Is AI’s hallucination problem fixable? AP News. https://apnews.com/article/artificial-intelligence- hallucination-chatbots-chatgpt-falsehoods-ac4672c5b06e6f91050aa46ee731bcf4

Owen, D. (2024). Civics in the digital age. Civic Education Research Lab at Georgetown University. https://cerl.georgetown.edu/civics-in-the-digital-age/

Panditharatne, M. (2024, May 9). The election year risks of AI. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/election-year-risks-ai

Pelosi, N. (2024, July 1). Pelosi statement on Supreme Court decision violating the foundational American principle that no one is above the law. Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi,

California’s 11th District newsletter. https://pelosi.house.gov/news/press-releases/pelosi- statement-supreme-court-decision-violating-foundational-american

Perrin, A. J., & Gillis, A. (2019). How College Makes Citizens: Higher Education Experiences and Political Engagement. Socius, 5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119859708

Savaget, P., Chiarni, T., & Evans, S. (2019). Empowering political participation through artificial intelligence. Science and Public Policy, 48(3), 369-380. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy064

Scott, M. (2024, April 16). Deepfakes, distrust and disinformation: Welcome to the AI election. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/deepfakes-distrust-disinformation-welcome-ai- election-2024/

Stamm, L. (2009) Civic Engagement in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices. Journal of College and Character, 10(4). DOI: 10.2202/1940-1639.1050. https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-1639.

Summers, V. R. (2024). The power of AI for educators. Self-published.

Sutton, G. (2024, May 1). Why Warner University stands against student use of AI. Warner University News. https://warner.edu/why-warner-university-stands-against-student-use- of-ai/

Sweeney, L. (2024, February 16). Deepfakes and ‘the liar’s dividend’ – Are we ready for the future of AI journalism? Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-17/ai-journalism-future-deepfakes-and-the-liars- dividend/103456062

Teachflow (2023). AI simulations: Revolutionizing civic education and empowering future leaders. AI Simulations: Revolutionizing Civic Education and Empowering Future Leaders – Teachflow.AI.

Thomson, T., & Thomas, R. (2023, July 9). Ageism, sexism, classism, and more: 7 examples of bias in AI-generated images. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ageism- sexism-classism-and-more-7-examples-of-bias-in-ai-generated-images-208748

Torgeson, C. (2023, March 31). AI’s threat to writing. The Case Western Reserve Observer. https://observer.case.edu/ais-threat-to-writing/

Trump v. United States, 603 U.S. (2024). Case No. 23-939. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-939_e2pg.pdf

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. (2023, May). Artificial intelligence and the future of teaching and learning: Insights and recommendations. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/ai-report/ai-report.pdf

Vos, L. (2023, September). AI hurts students’ writing and communication skills. eCampus News. https://www.ecampusnews.com/featured/2023/09/21/ai-tools-students-writing- communication-skills/

Weatherby, L. (2024). The silicon-tongued devil. Jacobin, 52, 25-32. https://jacobin.com/2024/01/the-silicon-tongued-devil

Westheimer, J. J., Rogers, & J. Kahne (2014). The politics and pedagogy of economic inequality. PS: Political Science & Politics, 50(4), 1043-1048.

Young, J. R. (2024, March 26). Could AI give civics education a boost? [Audio podcast episode]. In EdSurge Podcast (ISTE). Soundcloud. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2024-03-26-could-ai-give-civics-education-a-boost

Zhang, W. (2022, April 30). Civic AI education: Developing a deliberative framework. EduCHI’22. https://educhi2022.hcilivingcurriculum.org/wp- content/uploads/2022/04/educhi2022-final12.pdf

Authors

Joseph P. Zompetti (Ph.D., Wayne State University) is a Professor of Communication at Illinois State University, where he teaches courses in political communication, social movements, and rhetoric. He is a recipient of three Fulbright grants to study in Sri Lanka, Brazil, and Kyrgyzstan. Relatedly, he is internationally known for his research and teaching of argument, critical thinking, political communication, democracy promotion, disinformation, and political engagement, as he has taught these and similar subjects in nearly 30 countries, including workshops and trainings to NGOs and youth organizations. Author of several scholarly books and articles, Zompetti’s most recent book, Divisive Discourse: The Extreme Rhetoric of Contemporary American Politics, is in its second edition and focuses on reducing the polarization in political discourse.

Lance R. Lippert (Ph.D., Southern Illinois University, 2000) is a professor in the School of Communication at Illinois State University in Normal, IL. He is the Program Coordinator for the Communication Studies Program in the School of Communication. His research interests include civic engagement pedagogy, effective workplace communication, health communication, organizational culture, and appropriate and therapeutic humor use. Dr. Lippert created and implemented the Civic Engagement and Responsibility Minor and Course Redesign program at ISU. He also received national recognition by receiving the “Barbara Burch” Award for Faculty Leadership in Civic Engagement from the ADP/AASCU in 2018. Lance has published on topics in the areas of organizational, health, and instructional communication. Over the last 25 years, he has consulted for various public, private, nonprofit, educational, and governmental organizations.

Stephen K. Hunt (Ph.D., Southern Illinois University, 1998) is a University Professor and former Director of the School of Communication at Illinois State University in Normal, IL. He served as President of the Central States Communication Association (CSCA) in 2011. Dr. Hunt specializes in instructional communication, debate, and communication pedagogy. His research reflects his interest in the pedagogy of civic and political engagement, persuasion, critical thinking and analysis and the assessment of communication skills. Dr. Hunt authored or coauthored numerous peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, and books including Engaged Persuasion in a Post-Truth Era, Engaging Communication, Quantitative Research in Communication, and An Ethnographic Study of the Role of Humor in Health Care Transactions.