Abstract

Civic education and civic leadership are at the forefront of renewing faith in democracy on our campuses and communities. There is an urgent need for higher education to return to its historical foundation to fulfill the mission of democracy by educating students for democratic citizenship (Harkavy, 2006). Effectively integrating curricular and co-curricular civic engagement involves a balanced approach that is “both political and non-political” (Ehrlich, 2000, p. vi) to guide students to identify core values, develop civic knowledge, and build civic leadership skills (Finley, 2011; Hurtado, 2019). Civic leadership is an integral student learning outcome embedded within civic engagement praxis, but few frameworks have been developed to integrate leadership growth into their programming and curricula (Kniffin & Sapra, 2021). To renew faith in democracy, a reorientation to engagement with the local community through civic leadership is the pathway to achieve measurable impact by guiding students from the classroom into the community. If higher education is to fulfill the mission of democracy, educators and campus leaders must become the guides who invite students into a story bigger than themselves. Building on King’s (1963) civic legacy and Musil’s (2009) Civic Learning Spiral, the author outlines a Strategic Leadership Impact Model that has resulted in student-led civic engagement capstone projects, community-based research, and sustainable civic partnerships. Whether in the classroom or in the community, undergraduate students must be equipped through civic curriculum, co-curriculum, and service-learning programming to engage diverse perspectives and political viewpoints with civic curiosity to become effective civic leaders.

In the same way that the foundational goal of America is freedom, the primary mission of American higher education is to fulfill the mission of democracy by educating students for democratic citizenship (Harkavy, 2006; King, 1963). One of higher education’s most important roles is to create spaces where undergraduate students can become engaged and informed citizens who are prepared to participate in the work of democracy. Colleges and universities are where undergraduate students begin to define their values and find their voice, engaging diverse perspectives and deepening a sense of being and belonging, on the path to developing individual civic leadership skills.

Institutions of higher education have begun devoting more attention and resources to discipline-oriented courses, service-learning programs, cohort-based civic problem solving, study abroad opportunities, living-learning communities, first-year college initiatives, general education curriculum reform, and community-based research (Leskes & Miller, 2006; Musil, 2009; Hurtado, 2019; Pope & Surak, 2020). Despite the expansion of civic education efforts at American colleges and universities throughout the 21st century, a common definition for civic engagement does not exist (Finley, 2011; Hatcher, 2010). In Civic Engagement in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices, Jacoby and associates (2009) set out to inform and inspire faculty, staff, and academic leaders engaged in “educating students for civic engagement or preparation for active democratic citizenship” (p. 1) by outlining best practices for civic responsibility in higher education. Jacoby (2009) elaborates on the reasons why a consensus definition for civic engagement is such a challenge:

There is widespread recognition that defining civic engagement presents formidable challenges. In fact, there are probably as many definitions of civic engagement as there are scholars and practitioners who are concerned with it. Civic engagement is a complex and polyonymous concept. In addition, scholars and practitioners use a multiplicity of terms to name it, including social capital, citizenship, democratic participation/citizenship/practice, public work / public problem solving, political engagement, community engagement, social responsibility, social justice, civic professionalism, public agency, community building, civic or public leadership, development of public intellectuals, and preservation and expansion of the commons (p. 6).

Regardless of the challenges and barriers to defining civic engagement, there have been countless collaborative and inter-collegiate councils, working groups, development teams, and accreditation agencies who have been commissioned to develop common definitions and rubrics for civic education (Musil, 2009; Hatcher, 2010; Hurtado, 2019). Civic education is generally focused on preparing educators and students to be good and productive citizens in democracy (Carr, 2008). This includes expansion of civic knowledge through experiences and communal dialogue that deepens awareness regarding diversity, equity, social justice, inclusivity, and political engagement.

Polarization & the Responsibility for Democratic Renewal

After examining the complex and contested definitions of civic engagement and civic leadership, Kniffin and Sapra (2021) summarized the complexity by concluding that “civic engagement is itself an act of leadership” (p. 1). Leskes and Miller’s (2006) assertion that civic learning is the “ability to understand and participate in decisions that shape and influence a diverse democratic society” (p. 3) is notable for its succinctness and learner-centric language. Bringle and Hatcher (2009) have offered a useful definition that incorporates service-learning courses, community-based research, and faculty professional service: “Civic engagement can occur through teaching, research, or service that is done in and with the community” (p. 39). This subtle distinction about civic work “in” and “with” the community is a solid example of terms that make a definition of civic engagement a moving target.

Fundamentally, civic engagement is about how individuals and communities exercise their political power (Holley, 2012). Similarly, Ehrlich’s (2000) definition of civic engagement, which is widely accepted and cited by many institutions and organizations, emphasizes a balanced approach to civic life that embraces both the “political and nonpolitical processes” to guide students to identify their core values, develop civic knowledge, and build civic leadership skills (p. vi). Even without a consensus definition of civic engagement, American higher education plays a distinct historical role in educating citizens for public leadership in society. A common definition of civic engagement should focus on active participation in and with the life of the community to lead change, strengthen democracy, and engage the public good.

Educators who guide students from the classroom into the community cannot avoid the inevitable emergence of “political” discourse amidst “nonpolitical” civic action, which will emerge naturally through community engagement, and will provide their students the opportunity to develop their political ideals and beliefs while they are leading and learning.

Involvement in civic and political life leads to less polarized political views and opens the worldview of the participant to new perspectives and contributes to bridging political divides (Kleinfeld, 2023). Political polarization, where beliefs and attitudes become more extreme and divided, has been observed for centuries and is a recurring theme in the development of political systems. Polarized public discourse and ideological divisions are not new phenomena in democratic societies (Hofstadter, 1969; Hansen, 1991; Tackett, 1996), although the 24-hour news cycle and social media algorithms have contributed to increased cultural divisions (Carothers, 2019) and heightened the issues surrounding confirmation bias, misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, 2017).

Political discourse is an essential aspect of civic education, and engagement with the local community inherently involves the political attitudes and actions of the stakeholders and members of the community (Levy, et al, 2019). When civic learning is limited to an “apolitical” experience, students are not encouraged to cultivate civic awareness through “processes of negotiation” that places their individual knowledge within the tension of the wider societal context of the community (Finley, 2011, p. 4). Renewing faith in democracy is a complex and wicked problem that requires a balanced approach which will allow students to engage in conversations with their peers while also participating in the local civic life of the community. The responsibility for democratic renewal is historically placed upon each local campus to ensure that the democratic mission remains “the primary mission of American higher education” (Harkavy, 2006, p. 11). The time is now for our institutions to train inclusive and courageous civic leaders to “advance civic learning and safeguard our democracy” (Hurtado, 2019, p. 105). Amidst the onslaught of polarization in our society, colleges and universities cannot afford to outsource civic education and civic learning if we hope to renew faith in democracy and restore the purpose of higher education among our students and our communities.

Civic Education for Civic Leadership

The emergence of scholarship and academic research concerning leadership and civic engagement has developed along similar timelines over the past thirty to sixty years, however, these two fields of study are not always integrated through intentional educational practice (Kniffin & Sapra, 2021). Research synthesis in higher education has shown that an engaged pedagogical approach for coursework and campus programming is the most effective way to enhance civic learning and develop civic leadership among undergraduate students. To develop democracy-building skills, curricular and co-curricular civic engagement interventions should emphasize the integration of collaborative problem-solving, deliberative intergroup dialogue, and service-learning activities (Finley, 2011; Hurtado, 2019). When leadership education is integrated into civic engagement curriculum, co-curriculum, and service-learning programming, students are given the opportunity to view their personal growth through an integrated lens while they are engaged in the practice of community engagement.

Conceptions of civic leadership have evolved rapidly since the four great social movements — civil rights, grassroots, environmental, and women’s — of the 20th century, shifting the responsibility of civic imagination and civic action from “those at the highest levels of the social hierarchy” with positional power and ascribed affluence to “ordinary citizens” with situational authority and authentic vision for their community (Chrislip & O’Malley, 2013, p. 4). This civic leadership evolution has served to democratize leadership at the same time that the world has moved from an age of industrialization to an age of information to an age of curation with an incredible swiftness that could only have been predicted in fantasy-filled science fiction novels 100 years ago. Civic leadership is most impactful and remarkable when the habits of democracy are practiced in the immediate context of our neighborhoods and campuses, not through the empty promise of charisma or the false promise of ascendency, but through a return to revitalized democratic purpose.

In the face of political polarization, the sheer enormity of the challenge for higher education institutions to reclaim their place as those who educate citizens for citizenship in democracy is daunting, but civic education that integrates civic leadership into curricular and co- curricular interventions that educate students for the public good (Chrislip & O’Malley, 2013; Hurtado, 2019). When educators and campus leaders place a high priority on educating college students as emerging civic leaders by “actively solving strategic, real world, problems in their local community, a much greater likelihood exists that they will significantly advance citizenship, social justice and the public good” (Harkavy, 2006, p. 33). To fulfill its historic public purpose, colleges and universities must continue innovating through curricular and co-curricular civic education that empowers students to develop individual and collective civic imagination and civic curiosity.

Civic Curiosity: Democracy is Life!

Civic leadership is a measurable attribute of civic engagement and should be viewed as an attainable student learning outcome by educators and campus leaders. Research shows that curricular and co-curricular civic education that integrates “purposeful, conscious and intentional, thus more effective” leadership learning outcomes can be thoughtfully designed with significant interventions and experiences (Chrislip & O’Malley, 2013, p. 10). However, as long as civic learning and civic leadership are viewed as an elective and optional undergraduate pathway for students, there will continue to be many who miss the opportunity to develop their skills for democracy and leadership through civic engagement. Democracy cannot be contained within any specific discipline, program, institute, or classroom because democratic education should be pervasive, placing the responsibility of civic education for civic leadership in the interdisciplinary context of every campus leader.

The restrictive impact of siloing in the university system has been researched and lamented at length (Harkavy, 2006). The fragmented organizational structure and disciplinary divisions of modern universities and colleges “work against collaborative understanding and helping to solve highly complex human and societal problems” (Harkavy, Hartley, Hodges, & Weeks, 2013, pp. 528-529). In 1982, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development published a report exploring the relationship between higher education and the community in which the authors pointedly remarked, “Communities have problems, universities have departments” (Center for Educational Research and Innovation, 1982, p. 127). Isolationism, like political polarization, hinders the cultivation of civic curiosity and restricts the renewal of democratic life.

As an educator, my highest calling is to invite students into a story bigger than themselves. I believe that every student is a leader with the potential to impact their community. Through my teaching in Interdisciplinary Studies, the Clarke Honors College, and my campus leadership as coordinator of the PACE Presidential Citizen Scholars Program at Salisbury University, I guide students to collaborate with community leaders to investigate areas of specific and reciprocally beneficial interest. Because of the ambiguity and complexity surrounding prevailing definitions of civic engagement and leadership, I emphasize the cultivation of civic curiosity and civic imagination in my pedagogical approach.

Civic curiosity is a learning approach and an attitude that includes a commitment to remain informed and involved in the democratic process and public life of the local community. Civic imagination is the capacity to imagine innovative and inclusive ways to make the world a better place. Within the PCS Program, my students gain experience, knowledge, and mentoring from the local, state, and regional relationships they develop with community leaders and elected officials who collaborate with them in their civic engagement capstone projects. When my students face the inevitable challenges within their civic work, civic curiosity and civic imagination provide an invitation to envision creative pathways to accomplish public good.

There are many disciplinary examples for educators to creatively integrate civic engagement into their curricular and co-curricular planning (Finley, 2011), but there are two distinct models that I utilize to guide my students to cultivate civic curiosity and civic imagination for strategic leadership development and mindful citizenship: a person and a framework.

The Letter from Birmingham Jail

The historical example of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership provides a model for educators and students who seek to reclaim the mission of higher education: to fulfill the mission of democracy. An artifact from Dr. King’s legacy of civic leadership which offers a depth of interdisciplinary analysis is the Letter from Birmingham Jail (King, 1963). Dr. King’s civic life is a powerful reminder that leadership is not about otherworldly heroism and outrageous superhumanism, but about ultra-ordinary people who act with compassion and justice in the context of our living rooms, our classrooms, and among our neighbors. The artifact itself is contextually grounded in the Civil Rights Movement of America in the 1960s, but the work for civil rights is never-ending.

On April 16th of 1963, while imprisoned for marching against racist segregation, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed the Letter from Birmingham Jail to eight white clergymen who had written an open letter to the Black community denouncing the nonviolent campaign by naming their actions in Birmingham as “unwise and untimely.” In the letter, Dr. King placed the struggle against injustice in the wide global context, and he spoke directly to the clashing of worldviews that had led to this tension-filled moment in 1963. In one of the most bold and clear declarations against the temptation for humans to compartmentalize local injustice while ignoring the individual responsibility of the whole global human community, Dr. King (1963) wrote these words:

I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly (p. 79).

These inspiring words serve as a call to action for educators and students. We must not be those who find ourselves on the sidelines, or those who pretend that we are unaffected by the persecution of our neighbors. The work of social justice is perpetual and pervasive. When we see discrimination, injustice, and ignorance today, we must follow Dr. King’s example to shed any pretension that the work of civic education and civic leadership is mere futility. The “inescapable network of mutuality,” in which we are all caught, demands that civic educators push back on the temptation toward worldview reductionism. And instead, we must do the hard work of listening and understanding which leads to courageous compassion. Dr. King’s call to action against segregation echoes in our generation to engage the ignorant disease of xenophobia. The “single garment of destiny” to which we are all tied demands that we root out ignorance in the pursuit of understanding that can inspire the sort of civic curiosity which will move students beyond the walls of the classroom to engage their neighbors.

The call to civic courage still resonates as “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” in our local communities and campuses. Educators and students can follow leaders like Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to shape our civic actions in the context of our colleges and universities through incarnational civic leadership. Dr. King’s leadership legacy is not owned by any single organization, state, or nation. The civic leadership legacy of MLK is a global force for “all interrelated communities” where justice is denied because the whole of humanity is connected in a “single garment of destiny” (King, 1963). When undergraduate students are given the opportunity to interact with the legacy of civic imagination through a historical text such as Letter from Birmingham Jail, they are better equipped to imagine new pathways to engage the wicked problems in their community. Because the “pursuit of social justice is at the heart of civic leadership activity” (Kliewer & Priest, 2017, p. 6) it is imperative that campus leaders and educators provide a foundation for civic curiosity by inviting students to contemplate the courage to no longer “sit idly by” on their campus and community.

The Civic Learning Spiral

As higher education institutions have become recommitted to their public purpose through community-based programming and civic education, frameworks that guide faculty and campus leader considerations for engagement while also measuring civic learning outcomes for students can be leveraged to provide conceptual guidance (Pope & Surak, 2020). The Civic Learning Spiral (Musil, 2009) is one example of an integrated framework that has received wide support among civic engagement practitioners and educators in higher education (Hatcher, 2010; Hurtado, 2019). In Purposeful Pathways, Leskes & Miller (2006) outline the usefulness of spiral theories of student learning for the “expansion of experiences and an increasing level of cognitive complexity” (p. 7). In general, spiral theories are useful frameworks for non-linear learning through layers of deepening complexity in categories such as human development, public opinion, and civic knowledge.

As part of AAC&U’s five-year initiative, Greater Expectations: Goals for Learning as a Nation Goes to College, Musil (2009) worked within a civic engagement working group of educators and nonprofit leaders to develop the Civic Learning Spiral through a series of forums in six cities (p. 59). Musil (2009) notes that the Spiral’s framework was developed to consolidate three contemporary reform movements of diversity, global learning, and civic engagement in higher education with the goal to “establish the habit of lifelong engagement as an empowered, informed, and socially responsible citizen” (p. 59). The Civic Learning Spiral is formed around six braids (or domains) that coexist simultaneously as a fluid and integrated continuum within the student learner: self, communities and culture, knowledge, skills, values, public action. The six braids of the Spiral are designed to measure and shape civic education for curricular and co-curricular experiences.

Hurtado (2019) frames the civic learning outcomes by inviting students to become active participants in each of the six dimension to develop civic imagination and civic habits as they engage the community and reflect on their experiences as a civic leader: Increasing an understanding of self in civic learning involves developing one’s own identity, voice, reflective practice, and sense of purpose. Communities and cultures outcomes include the development of empathy and appreciation for diverse individuals and communities, the capacity to transcend one’s own embedded worldviews, and the recognition of inequalities that impact underserved communities. Knowledge outcomes involve understanding knowledge as socially constructed; information literacy in this era of “alternative facts” and misinformation, including the capacity to understand scientific evidence and critically evaluate sources of authority; and deep knowledge of key democratic principles, processes, and debates that inform one’s major or area of study. Skills include conflict resolution, deliberation, and community-building, as well as the ability to work collaboratively and communicate with diverse groups. Values outcomes include ethical and moral reasoning and democratic aspirations such as equality, liberty, justice, and interest in sustaining the arts and sciences for the public good. Lastly, public action outcomes include students’ participation in democratic processes and structures, multiple forms of action and risk-taking to promote social progress, and ally behaviors such as working alongside communities in need to solve important problems (p. 98).

As I have deployed the Civic Learning Spiral, my students have consistently expressed that the weakness of the Spiral is the challenge of visualizing the interconnected braids. When teaching the Spiral, I often draw a simple sketch of six vertical lines to illustrate a “side-view” and then offer the visual of conch shell to demonstrate what a possible “top-view” of the braids spiraling in symmetry. Both analogies are imperfect, but they serve to provide my students with a starting point for contemplation. On the contrary, I have found that the Spiral’s greatest strength rests in the emphasis on relationships as an integral part of civic learning.

The Strategic Leadership Impact Model

Over the course of each semester, through teaching on campus and leading in the community, I have developed a more effective framework to guide my students in understanding the work of civic engagement and envisioning themselves as civic leaders. The Strategic Leadership Impact Model (Weaver, 2024) is designed to work in harmony with Musil’s (2009) Civic Learning Spiral, building on the cognitive complexity of the Spiral’s frame and clarifying the strategic movement for each stage of a civic project. The primary aim of the Strategic Leadership Impact Model is to guide student leaders, higher education staff/faculty, community partners, and civic stakeholders toward missional alignment to maximize the impact of civic leadership. The model’s movement should be from the campus into the community, and the model’s impact is rooted in authentic relationships.

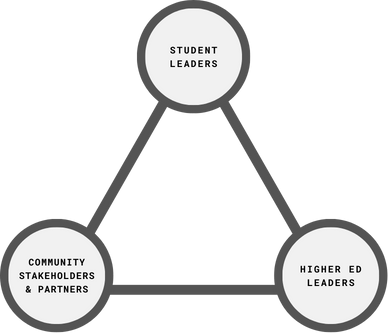

To express the roles of the three members of a civic action coalition, the SLI Model incorporates the Civic Action Triangle (see fig. 1) to illustrate the civic partners as they work together for mutual civic outcomes and research: community stakeholders & partners, higher education leaders, and student leaders (Weaver, 2024). One useful element of the Triangle is the simplicity of the framework, which provides each group an opportunity to see themselves moving forward in strategic reciprocal partnership, clarifying one another’s responsibilities, while also imagining the impact that the collective civic action might have on the community and emphasizing the community’s voice in civic engagement by asking: Who is missing? And who needs to be included as we move forward together?

With the Triangle model, students can quickly envision themselves as civic leaders, empowered to initiate civic action by identifying a significant civic issue and cultivating community and campus relationships for collaborative civic engagement. The goal of civic education for civic leadership is to guide students to view their campus and community with civic imagination and civic curiosity, while providing them with the courage and skills for democratic renewal. The Civic Action Triangle is a starting point for students to begin moving from the sidelines and into the public life of their community. Additionally, the Triangle serves as a poignant reminder to me, as the educator, that interdisciplinary collaboration with vibrant campus and community leaders is a necessary aspect if I hope to guide my students to accomplish public good. Territorialism will always undermine collaboration, and a defensive mindset deprives my students of the opportunity to become civic leaders with the skills to build and sustain authentic relationships through diversity in civic learning. I employ the Triangle to guide my students to identify potential civic partners and then release them to collaborate with campus leaders, community leaders, and other stakeholders as they refine their civic action plan, develop discernment, and integrate personal leadership growth into their engagement strategies.

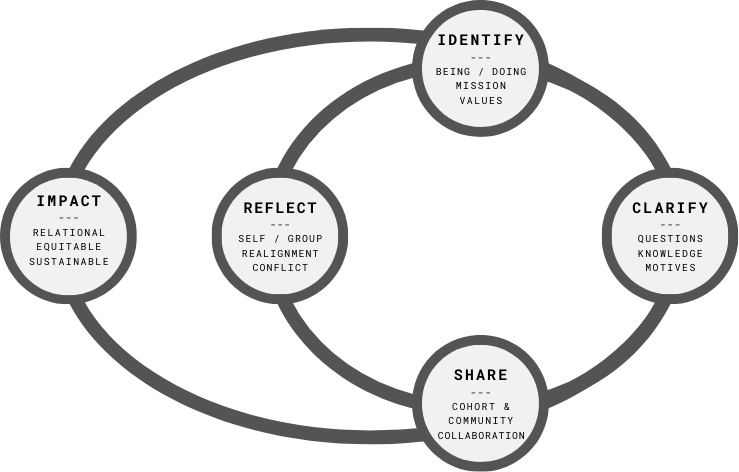

Throughout the process, the six braids of the Civic Learning Spiral (self, communities and culture, knowledge, skills, values, public action) are an important touchstone for my students to return for reflection and re-alignment. As noted previously, the Spiral’s weakness is in the lack of a clear visualization of the model from Musil (2009) and the civic engagement working group. After guiding my students to better understand the mutually beneficial partnership (Bringle & Hatcher, 2009) between community stakeholders & partners, higher education leaders, and student leaders through the Triangle framework, the Strategic Leadership Impact Model (see Fig. 2) serves to launch students from the public action braid of the Spiral into a more fundamental movement to overcome inertia and begin taking civic action.

The Strategic Leadership Impact Model offers a practical framework for all stakeholders to move clockwise through the double-loop, beginning with the identification of a common issue or research gap.

One clear strength of the Strategic Leadership Impact Model is in the deliberate reflection that the double loop provides students, community leaders, and campus leaders when they are seeking a reciprocal civic outcome. Another strength of this model is the visualized element of the model that offers way-finding function for community stakeholders and partners, higher education leaders, and student leaders to map their progress. Each stop on the two loops is a pause point of reorientation for the student leaders, higher education staff/faculty, community partners, and civic stakeholders to outline their objectives, clarify their motives, refine their responsibilities, and align the reciprocal benefits for the collaborative work. At each stop on the loops, we ask:

Identify — What issues are people talking about in your community?

Clarify — What questions are essential to strategic conversations and potential actions to engage this issue?

Share — Who do you know that is already doing work around this issue and where are they gathering?

Reflect — Where does conflict exist that may be keeping you from moving forward in alignment to make an impact?

Impact — Is the impact of our civic work relational, equitable, and sustainable? (If not, return to the first loop to clarify).

The application of the Civic Action Triangle and the Strategic Leadership Impact Model integrates narrative pedagogies because stories help us make sense of the complex world around us and help us to establish a framework for the development of some of the core competencies of growth and maturity in leadership: diagnosing, communicating, and adapting as we learn and lead amid of the messiness of civic work (Fleming, 2001). The Civic Learning Spiral supports narrative exposition by asking students to reflect on self, values, and the greater context of the communities and culture in which we are leading, teaching, researching, and serving “in and with the community” (Bringle and Hatcher, 2009, p. 39). Studying and integrating MLK’s legacy of nonviolent civic action equips students to imagine new pathways to engage the significant issues in their community and become inspired to seek peace by doing justice. The Strategic Leadership Impact Model is a civic education framework that scaffolds the impact of Dr. King’s (1963) incarnational civic legacy and Musil’s (2009) civic spiral. Models that guide students to identify core values, develop civic knowledge, investigate inequities in the community, and build civic leadership skills are vital to educating students for equitable and inclusive citizenship.

Conclusion

If higher education is to fulfill the mission of democracy, educators and campus leaders must become the guides who invite students into a story bigger than themselves. Seeking equity and justice in our messy homeplaces, workplaces, and marketplaces demands an approach to civic learning that gives priority to challenging conversations, deliberative dialogue, and civic reflection that opens the way for new knowledge and personal growth to awaken awareness and understanding. Civic curiosity inspires movement away the frequented places (homes, schools, departments, neighborhoods) and companionable knowledge (disciplines, theories, ideologies, perceptions) where we have become far too comfortable. Campus faculty and staff may be a natural starting point for colleges and universities to reclaim their role in the community as agents of democratic renewal, but the work of democracy cannot remain limited to any one specific discipline, program, department, institute, or classroom on campus. The work of renewing faith in democracy is our responsibility to share.

Creating and sustaining community partnerships that produce local and regional impact through mentoring and interdisciplinary collaboration is a measurable outcome of civic engagement. The cultivation of relationships is at the heart of civic engagement. Civic education reinforces and supports democratic renewal through diverse frameworks and models that inspire civic imagination. Whether in the classroom or in the community, undergraduate students must be equipped through civic curriculum, co-curriculum, and service-learning programming to engage diverse perspectives and political viewpoints with civic curiosity to become effective civic leaders.

References

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (2009). Innovative practices in service learning and curricular engagement. In L. Sandmann, A. Jaeger, & C. Thorton (Eds.), Institutionalizing community engagement in higher education (pp. 37-46). New Directions for Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Carothers, T. (2019). The long path of polarization in the United States. In T. Carothers & A. O’Donohue (Eds.), Democracies divided: The global challenge of political polarization (pp. 65–92). Brookings Institution Press.

Carr, P. (2008). Educating for democracy: With or without social justice. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(4), 117-136.

Center for Educational Research and Innovation. (1982). The university and the community: the problems of changing relationships. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Chrislip, D. D., & O’Malley, E. J. (2013). Thinking about civic leadership. National Civic Review, 102(2), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.21117

Ehrlich, T. (2000). Civic responsibility and higher education, Preface, p. vi. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Finley, A. (2011). Civic learning and democratic engagements: A review of the literature on civic engagement in post-secondary education. Paper prepared for the U.S. Department of Education.

Fleming, D. (2001). Narrative leadership: Using the power of stories. Strategy & Leadership, 29(4), 34-36.

Harkavy, I. (2006). The role of universities in advancing citizenship and social justice in the 21st century. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 1(1), 5-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197906060711

Harkavy, I., Hartley, M., Hodges, R. A., & Weeks, J. (2013). The promise of university-assisted community schools to transform American schooling: A report from the field, 1985–2012. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(5), 525-540. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2013.834789

Hansen, M. H. (1991). The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes: Structure, Principles, and Ideology. University of Oklahoma Press.

Hatcher, J. A. (2010). “Defining the Catchphrase: Understanding the Civic Engagement of College Students.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 16(2), 95-100.

Hofstadter, R. (1969). The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780-1840. University of California Press.

Holley, K. (2016). The principles for equitable and inclusive civic engagement: A guide to transformative change. Columbus, OH: The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University.

Hurtado, S. (2019). Daedalus, Fall 2019, Vol. 148, No. 4, Improving Teaching: Strengthening the College Learning Experience (Fall 2019), p. 94-107. The MIT Press on behalf of American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Jacoby, B. (2009). “Civic Engagement in Today’s Higher Education: An Overview” in Civic Engagement in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices, ed. Barbara Jacoby, 1-29. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

King, M. L. Jr. (1963, August). The Negro is your brother. The Atlantic Monthly, 212(2), 78-88.

Kleinfeld, R. (2023). Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/09/polarization-democracy-and-political- violence-in-the-united-states-what-the-research-says?lang=en

Kliewer, B. W., & Priest, K. L. (2017). Why civic leadership for social justice? eJournal of Public Affairs, 6(1).

Kniffin, L. & Sapra, S. (2021). “Enhancing Civic Engagement Through Leadership Education,” eJournal of Public Affairs: Vol. 10: Issue 3, Article 3.

Leskes, A., & Miller, R. (2006). Purposeful pathways: Helping students achieve key learning outcomes. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Levy, B., Babb-Guerra, A., Batt, L. M., & Owczarek, W. (2019). Can Education Reduce Political Polarization? Fostering Open-Minded Political Engagement during the Legislative Semester. Teachers College Record, 121(5), 1-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912100503

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Musil, C. (2009). “Educating students for personal and social responsibility: The civic learning spiral” in Civic Engagement in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices, ed. Barbara Jacoby, 49-68. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pope, S., & Surak, S. (2020). Discipline-oriented citizenship. eJournal of Public Affairs, 9(2), 1-20. https://www.ejournalofpublicaffairs.org/discipline-oriented-citizenship

Tackett, T. (1996). Becoming a Revolutionary: The Deputies of the French National Assembly and the Emergence of a Revolutionary Culture (1789-1790). Princeton University Press

Author

Ryan Von Weaver is a Lecturer at the Institute for Public Affairs and Civic Engagement and Interdisciplinary Studies at Salisbury University (Salisbury, MD). Ryan coordinates the PACE Presidential Citizen Scholars Program. As an educator, Ryan believes that every student is a leader, every story is significant, and his highest calling is to invite students into a story bigger than themselves. In each learning community, Ryan’s goal is to guide students to move from the classroom into the community to engage significant issues through civic leadership, community- based research, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Ryan grew up in the Red River Valley and relocated with his family to the Chesapeake Bay region where he has been a nonprofit leader and engaged citizen for almost twenty years. Ryan holds a graduate degree in leadership from the the University of Oklahoma. Ryan believes that story is the most powerful pathway for understanding, motivation, and belonging in democracy.