Author Note

Laura E. Martin, McLean Institute for Public Service and Community Engagement, University of Mississippi.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Laura E. Martin, Associate Director, McLean Institute for Public Service and Community Engagement, University of Mississippi, P.O. Box 1848, University, MS 38677. Phone: (662) 915-2078. Email: lemartin@olemiss.edu

Abstract

This article explores how a national service program, the Mid-South VISTA Project (MSVP), has impacted community partner organizations through capacity-building activities. Housed at Mid-South University (MSU, a pseudonym), MSVP extends the community-engaged activities of campus units while building capacity at partner organizations. The project takes into account dimensions of nonprofit capacity building and how to navigate the community–campus partnership process in the context of the AmeriCorps VISTA program. The data presented in this article are part of a larger case study focusing on the impact of MSU’s community engagement center programs on community partner organizations. Findings from interviews with 15 VISTA supervisors guided the development of an evaluation plan that uses logic model domains to center mission alignment and reciprocity as outcomes of the partnership process.

Keywords: community engagement, national service, capacity building, higher education, case study

As the community engagement field evolves, there remains a consensus around the importance of elevating community voices from the margins (Littlepage et al., 2012; Sandy & Holland, 2006; Stoecker & Tryon, 2009), alongside an acknowledgment of the challenges inherent in assessing impact at the community level (Cruz & Giles, 2000). Researchers at the Urban Institute noted that “although enhancing the capacity of nonprofit groups is not synonymous with building healthy communities, there are important linkages that need to be explored” (De Vita et al., 2001, p. 5). The activities of nonprofit organizations—and the organizational capacity underpinning their ability to implement their missions—offer a framework for evaluating the impact of community engagement in higher education. This article explores how a national service program, the Mid-South VISTA Project (MSVP), has impacted community partner organizations through capacity-building activities. Findings from interviews with 15 VISTA supervisors guided the development of an evaluation plan that uses logic model domains to center mission alignment and reciprocity.

The Mid-South VISTA Project

MSVP is housed at the Center for Community Engagement at Mid-South University (MSU, a pseudonym). VISTA members complete full-time, yearlong terms of indirect national service during which they work to advance poverty alleviation, capacity building, sustainable solutions, and community empowerment (AmeriCorps, 2021). In contrast to direct service, or hands-on volunteer activities, indirect service builds capacity for host sites through activities such as volunteer management, partnership development, public communications, and fundraising.

MSVP partners with nonprofit organizations, Title I school districts, and community-engaged units on campus. The communities where VISTA members serve contend with persistent poverty, and disparities in income and educational attainment have resulted from centuries of disenfranchisement at the individual and structural levels; in these communities, legacies of racism and persistent underfunding for public education loom large (Duncan, 2014; Myers Asch, 2008). In the state, poverty and unequal access to resources and opportunities fall along racial lines, with power, resources, and influence being historically concentrated among White residents to the exclusion of Black residents (Duncan, 2014).

Many MSVP partner sites operate with very limited resources and staffing. It is imperative for MSVP to attend to the power asymmetries inherent in developing community–campus partnerships since the university can be perceived as a center of wealth, power, and influence (Dempsey, 2010). MSU also carries the burden of its legacy of forced integration (Cohodas, 1997; Eagles, 2009), which can create suspicion among prospective partners that have not historically felt welcome on campus.

Green (2013) conducted an initial program evaluation of MSVP in 2013, and researchers at the Center for Community Engagement completed a follow-up evaluation in 2017 using a survey and interviews. That process surfaced questions around mission alignment and how the university partnership could effectively guard against dependency. The interview data presented in this article were part of that larger study.

Literature Review

The VISTA program was initiated in 1964 as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty (Bass, 2013). Unlike with highly visible public works projects, data for measuring the effectiveness of VISTA were more elusive (Bass, 2013). While it was possible to count the number of VISTA members and beneficiaries enrolled in related programs, there was no consistent benchmark or approach for measuring the changes in attitudes and motivations of those beneficiaries (Bass, 2013). At the organizational level, a 1976 VISTA project survey identified an intriguing paradox, in which community self-reliance had increased yet organizations remained dependent on VISTA members (Bass, 2013).

Asymmetrical power relationships and resource dependency are key concerns in the community engagement literature (Kindred & Petrescu, 2015), in addition to unmet expectations (Sandy & Holland, 2006), the need to provide cultural competency training for students (Srinivas et al., 2015), and confusion about how to navigate the complex bureaucracy of higher education (Enos & Morton, 2003; Weerts & Sandmann, 2008). VISTA programs housed within higher education institutions can translate and bridge some of those divides, and building the capacity of community partners is one way to safeguard against power asymmetry and dependency.

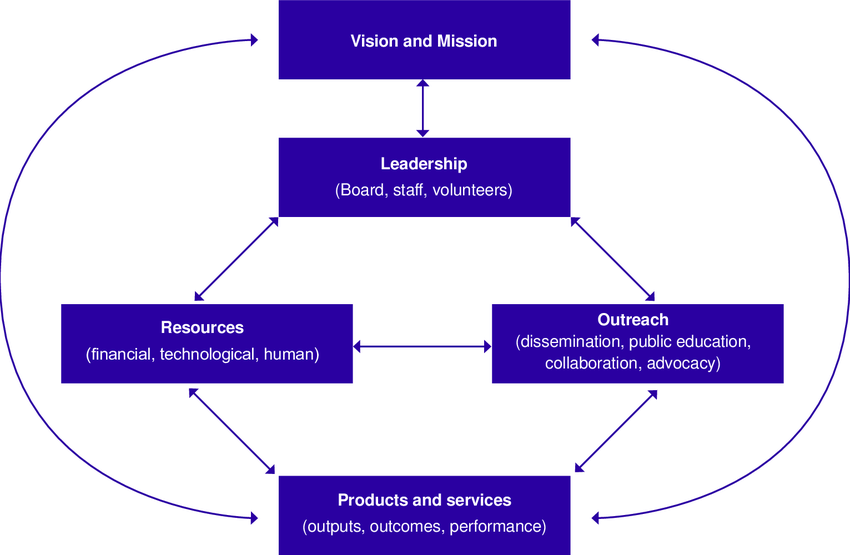

The concept of nonprofit capacity encompasses vision and mission, leadership, resources, outreach, and products and services (De Vita et al., 2001). Figure 1 shows the interconnectedness of these dimensions of capacity. VISTA members are positioned to contribute to nearly all of these areas, including volunteer management, resource development, outreach, and performance evaluation.

Figure 1

A Framework for Addressing Nonprofit Capacity Building

Note. Source: De Vita et al. (2001, p. 17).

Partnerships are central to how VISTA members build capacity for their organizations; community–campus partnerships also underpin community engagement activities in higher education. One of the fundamental dialectics in community–campus partnerships is that the time required to invest in the partnership—frequently a limiting factor for under-resourced nonprofit organizations—can also be the critical element that leads to transformative and growth-oriented partnerships (Clayton et al., 2010; Littlepage et al., 2012). Partnerships that build organizational capacity, such as VISTA placements, can alleviate those time constraints.

Community engagement researchers have also been clear that community voices are underrepresented in the literature (Littlepage et al., 2012; Sandy & Holland, 2006; Stoecker & Tryon, 2009) and that there is a need for empirical evidence demonstrating how these partnerships benefit community organizations (McNall et al., 2009). Recently, scholars have also focused on partnership processes that most benefit community partners (Adams, 2014; Srinivas et al., 2015; Tinkler et al., 2014). For instance, community partners have suggested that campus partners “learn how to talk together about racial, ethnic, and economic inequities and their causes with candor, and incorporate those discussions into community/campus partnership-building work” (Leiderman et al., 2002, p. 17), underscoring the importance of relationship building and partnership process.

Cruz and Giles (2000) distinguished between the partnership process and its outcomes. Process considerations include the equitable distribution of power and decision-making authority (Schulz et al., 2003), which enhances a sense of reciprocity. Citing Henry and Breyfogle (2006), Petri (2015) defined reciprocity in this way:

Two or more parties … take collective action toward a common purpose and in the process the parties are transformed in a way that allows for increased understanding of a full variety of life experiences, and over time works to alter rigid social systems. (p. 95)

Bringle et al. (2009) identified the importance of closeness, equity, and integrity in a partnership. Closeness involves the frequency of interactions, a range of collaborative activities, and mutual influence; equity ensures that outcomes are in proportion to investment; and integrity signals alignment between values and approaches. In the VISTA program, these process-oriented considerations must be balanced with performance measurements to justify grant funding and appropriations.

AmeriCorps (2019) currently assesses performance through capacity-building and poverty-alleviation metrics; the capacity-building measures presented in Table 1 were of particular interest in the present study.

Table 1

Capacity-Building Performance Measures

|

Strategic Plan Objective |

Outputs |

Outcomes |

Interventions |

|

Capacity Building and Leverage |

G3-3.4: Number of organizations that received capacity-building services |

G3-3.10A: Number of organizations that increase their efficiency, effectiveness, and/or program reach |

Volunteer management Training Resource development Systems development Donations management |

|

G3-3.1A: Number of community volunteers recruited or managed |

|||

|

G3-3.16A: Dollar value of cash or in-kind resources leveraged |

The preceding performance measures connect to the leadership, resources, outreach, and products and services domains identified by De Vita et al. (2001), and they flow into a logic model framework for developing a plan for evaluating organizational capacity building through national service and community engagement.

Methods

A logic model is a framework for facilitating program planning, implementation, and evaluation (Kellogg Foundation, 2004). As shown in Table 2, components of a logic model include: resources, which are used to accomplish activities; activities, which are actions to address the problem or challenge of interest; outputs, which provide evidence of service delivery; outcomes, which are changes that result from activities in the short term (1 to 3 years) and long term (4 to 6 years); and impacts, which are changes resulting from program activities in 7 to 10 years (Kellogg Foundation 2004).

The qualitative data presented in this article are drawn from a convenience sample of 15 in-depth interviews with VISTA supervisors which took place as part of MSVP site visits. The interview data are part of a larger data collection effort that has been ongoing since 2017, which was approved as exempt by the Institutional Review Board at MSU. Site visit interviews are conducted annually to explore how VISTA members contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of operations at their host sites. The 13 interview questions probe areas such as expectations, successes, challenges, mission alignment, impact, workplace environment, and MSVP partnership (see Appendix for the interview protocol). Qualitative data were analyzed using a constructivist approach to understanding the Center for Community Engagement as a case study and MSVP as the data source for understanding dimensions of capacity building among community partners (Creswell, 2007).

Participants and Analytic Process

The supervisors who participated in the site visit interviews represented the plurality of MSVP project partners during the 2017–2018 program year. Four additional interviews from the 2019–2020 year are included as they reflect perspectives of newer partners. Interview participants represented the following organizations, which have been de-identified to preserve anonymity:

- MSU campus-based

- School of Education

- Community engagement office at the medical center

- Residential college

- Gender equity center

- Material culture center

- STEM education center

- Community-based

- Afterschool and summer enrichment program in the Delta region

- Arts organization

- Boys and Girls Club in the Delta region

- Coalition of nonprofit organizations

- Community development office at a historically Black college

- Community farmers market supporting local farmers and low-income consumers

- Literacy-based organization

- Nonprofit organization supporting homeless families

The interview findings were analyzed inductively, and the coding process sought to maintain fidelity to the words spoken by respondents (Hycner, 1985; Thomas, 2006). A total of 454 codes emerged across the 15 interviews which reached a saturation point to reveal 19 categories (Hycner, 1985). The categories were mapped onto a logic model framework, in which each domain served as a theme. An overarching theme of alignment highlighted process-based dimensions of reciprocity which can help strengthen the quality of MSVP placements and partnerships.

Findings

The themes included the following: High Potential Placements (Inputs), Indirect Service and Direct Supervision (Activities), Extending Reach and Organizational Change (Outputs), and Dimensions of Alignment, construed as an overarching theme of reciprocity. Themes, categories, and code totals are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

MSVP Supervisor Interview Categories and Themes

|

Inputs: |

# of Codes |

Activities: Indirect Service and Direct Supervision |

# of Codes |

Outputs: |

# of Codes |

Reciprocity: Dimensions of Alignment |

# of Codes |

|

Goals and expectations |

15 |

Organization is doing more |

49 |

Organizational partnerships and outreach |

24 |

Host site mission alignment with MSVP |

32 |

|

Scope of VISTA role |

13 |

Volunteer engagement |

9 |

Broader community reach |

31 |

Supervisor investment in MSVP network |

25 |

|

Staff of 1 |

12 |

Resource development |

10 |

Validation of university partnership |

10 |

Member connection to VISTA and MSVP |

17 |

|

Qualities of a high- performing VISTA |

49 |

Role and orientation of VISTA supervisor |

40 |

Institutional change at MSU |

20 |

Support from MSVP |

21 |

|

Characteristics of a well-aligned VISTA placement |

28 |

Challenges when VISTA placement is not going well |

24 |

MSVP reporting and mechanics |

25 |

||

|

Total Codes |

117 |

132 |

85 |

120 |

Inputs: High Potential Placements

The High Potential Placements theme, construed as Inputs, frames how partner organizations can maximize a VISTA placement. Preparation for recruiting and placing a VISTA member requires the Center for Community Engagement and host site to identify common goals and shared resources, working toward partnership characterized by closeness, equity, and integrity (Bringle et al., 2009).

Supervisor interviewees shared a range of expectations for the VISTA term, from progress on specific tasks, such as volunteer management and issue research, to abstract contributions around program expansion and deepening partnerships. Some supervisors viewed capacity building through indirect service as a constraint for their understaffed organizations. One supervisor revealed that the VISTA had worked directly with third graders on test preparation, while another reflected that a previous VISTA probably would have preferred a direct service role.

Expansive expectations along with the narrowly tailored VISTA role can pose challenges for organizations that identify themselves as a “staff of one”—a frequent refrain among supervisors. A supervisor with the afterschool and summer enrichment program reflected that “at a small nonprofit, the expectation that each person does more than their job description is a given.” As the first VISTA at this nonprofit supporting homeless families, the member quickly learned about the programs and clients, overhauled financial education resources, and assembled his own desk. A dedicated VISTA member can be transformative for organizational initiatives, as the residential college director reflected: “We are a small office, so there is less time to set up community partnerships. It is a big deal to have a representative who is the face of service and connecting with the community.”

Multiple supervisors highlighted the ability of high-performing VISTA members to take direction and initiative, work independently, write well, communicate with supervisors, and stay organized. The director of the community engagement unit at the medical center reflected that a “VISTA needs baseline knowledge in order to know what questions to ask.” Ultimately, a high-performing VISTA in the right placement will increase the efficiency and effectiveness of their projects and overall operations. A VISTA can assume responsibilities that other colleagues at the organization have not had the capacity to take on; in the best case scenario, this creates sustainable new initiatives.

The director of the coalition of nonprofit organizations shared that “the [local campaign for grade-level reading] is now sustainable” after the hire of a full-time executive director funded by the local school districts. VISTA members supported these efforts over multiple years, and the development of the grade-level reading campaign as a standalone 501(c)(3) is a significant success and demonstration of sustainability. This director also addressed the tension between fighting poverty—a sustained effort—and a 1-year term of service: “In 1 year we are not going to witness gains; we must support members to trust the foundation” that they are building.

Activities: Indirect Service and Direct Supervision

The theme of Indirect Service and Direct Supervision represents the Activities domain of the logic model. The tension that emerged relates to the volume of activity that VISTA members can generate alongside the active supervision required to maximize those efforts.

For instance, the supervisor of the farmers market described capacity building in this way: “Now that [the VISTA member] is here, it’s not that I’m doing less work, it’s that the market can do more.” VISTA members drive organizational activity by developing new programs, events, partners, and beneficiaries; leading marketing and communications; collecting data; developing curriculum; conducting research; fundraising; and building systems to track donors and program participants. These activities align with several areas of nonprofit capacity identified by De Vita et al. (2001), such as resources, outreach, and products and services.

There is pressure to sustain initiatives created by VISTA members. Volunteer management and resource development can contribute to sustainability. The supervisor in the School of Education recognized the need for additional volunteers to support the expansion of a collegiate mentoring program started by a previous VISTA. While volunteer management is a very common activity for VISTA members, one supervisor noted the “challenging and sporadic” nature of volunteers in college towns. Other supervisors reported that VISTA members contributed to sustainability by conducting research to support fundraising; some had secured grants with minimal guidance.

Interviews revealed that the role of the VISTA supervisor influences success just as much as the qualities of the VISTA member. Many supervisors hold regular check-ins with VISTA members, generally on a weekly basis, to discuss progress. Beyond regular communication, many supervisors embraced a mentorship role, expressing sentiments such as, “VISTAs have given of their time to be part of the organization. We want to invest in them because they have invested in us,” and “I encourage the VISTA to ask more questions—to approach surface versus systemic fixes.” While MSVP asks supervisors to commit 5%–10% of their time to supervision, interview responses suggested that many supervisors invest far in excess of that benchmark.

The intensity of supervision was apparent for high-performing VISTA members and for those who needed more guidance. Multiple campus-based supervisors noted the challenge of VISTA start dates in September and January, introducing VISTA members at times in the academic calendar when supervisors are less available. Other supervisors addressed their own lack of availability (likely a function of expansive missions and small staff) as well as the need to intercede when VISTA members were “not as polished as the administration might have expected.” Multiple supervisors understood that the VISTA role was likely a first professional experience, and they shared processes they had developed to correct misspellings, grammatical errors, and other typos in emails. One supervisor noted the challenge of tracking performance measures when the VISTA member was not familiar with spreadsheets. Finally, the director of the community engagement unit at the medical center noted that the VISTA serving 2 hours from campus missed out on the camaraderie of other VISTAs serving on campus, signaling the importance of building rapport not only within placements, but also across the MSVP network.

Outputs: Extending Reach and Organizational Change

The Outputs theme of Extending Reach and Organizational Change reveals program expansion and a tangible increase in organizational capacity, which can be reinforced by the enhanced prestige of VISTA as a visible community–campus partnership.

The supervisor at the Boys and Girls Club shared that “there were no community events before the VISTA came on board.” The VISTA member increased parent engagement through a back-to-school night and a health fair. Similarly, the supervisor at the medical center noted that the VISTA member had taken leadership of a community health advocates program by featuring it at an engagement fair and developing a partnership with the K–12 school district to promote health careers among underrepresented groups. VISTA members also lead social media engagement, which was a focus of the VISTA member serving at the community development office at a historically Black college.

Increased outreach drives program engagement. The supervisor at the farmers market credited the VISTA member with “our best spring ever in terms of customer traffic, events, and social media.” Likewise, campus-based supervisors attested to an uptick in requests from local schools to provide enrichment programming, and credited the VISTA members with “allowing us to keep up with requests from teachers” and “allowing our center the opportunity to serve our state.” The director of the arts organization reflected that, historically, previous VISTA members had “launched programs and engaged new people,” and that now “people are reaching out to [us].” This director also shared their organization’s vision to “increase diverse artists and representation on the [organization’s] board.”

The topic of representation also surfaced in the discussion around partnerships and outreach. The VISTA member serving with the School of Education was a Black female who had graduated from a public school system in the Delta. In reflecting on efforts to build credibility at school districts where the majority of students are African American, the supervisor noted the positive impact of a “VISTA [who] looks like the people we are trying to impact.” The supervisor recounted a story about the VISTA member running into a former teacher when visiting the partner district. These personal connections enhanced the credibility of the School of Education and its efforts to make inroads in the Delta, where they had previously “encountered pushback against White people from the university trying to ‘save’ a school.” This account illustrates an opportunity to discuss racial inequity and power asymmetries while establishing new partnerships (Leiderman et al., 2002).

Community partners also referenced the credibility they had gained from aligning with MSVP. The farmers market director noted that “small nonprofits are regular people who want to do good, not survey methodologists.” This statement highlights how academic partnerships can support program evaluation, among other areas. The nonprofit coalition also expressed an interest in tapping university awareness, charitable giving, and volunteerism. In a similar vein, the director of the afterschool enrichment program in the Delta noted that “VISTA and the Center for Community Engagement have been our ‘in’ and a connection that has helped to access educational opportunities on campus.” This statement reinforces the role of MSVP as both a bridge and a conduit to forming additional partnerships on campus.

Other considerations relating to MSU were not always cast in a positive light. The nonprofit coalition receives many requests for financial assistance from MSU students who are not eligible for services at local agencies because they are not considered residents. Despite the organization’s status as a VISTA partner, they had not advanced conversations on campus around the need for additional resources for students facing financial insecurity. Taking a more active role in advocating for students experiencing poverty would require institutional change and commitment beyond VISTA. On campus, some VISTA supervisors spoke of a move, albeit a halting one, to institutionalize community engagement.

One supervisor noted that “faculty love the idea [of VISTA], but they are not as supportive as they could be.” This suggests that community engagement initiatives may be used for positive publicity rather than as instruments of institutional change. Another supervisor working to link a service-learning initiative across multiple schools at the medical center reflected on the importance of an “institutional understanding of how much work is required” to do effective community engagement, and that the “increased value-add to campus-based organizations was good for the administration to see.” Finally, the supervisor at the afterschool enrichment program in the Delta shared an outside perspective on how VISTA was slowly effecting change at MSU:

I am hopeful because this hasn’t historically been the work of Mid-South University. It’s great to partner with the Center for Community Engagement and VISTA. [The director of the Center for Community Engagement]’s connection to the Delta also strengthens the connection. The right people can institutionalize these structures.

Reciprocity: Dimensions of alignment

The overarching theme of Reciprocity encompasses Dimensions of Alignment, highlighting the partnership process. When mission alignment deepens to an integration of goals, partners move along the relationship continuum toward transformational partnerships by increasing closeness, equity, and integrity (Bringle et al., 2009).

Mission alignment resounded in the comments of many supervisors who identified education as a pathway out of poverty. As one community partner said, “We work to improve lives and meet needs by uniting people and resources—it’s an easy fit. VISTAs embody connection and a passion to make a difference.” Another commented, “It’s the same mission. [The VISTA host site] is focused on [Delta] county, while MSVP is a statewide partner in the work, doing the same work.”

Mission alignment also led to supervisor investment in the MSVP network. The interview with the farmers market director resulted in a potluck at the market to build relationships among VISTA members. Numerous supervisors expressed an interest in connecting with other VISTA partner sites, particularly those with similar focus areas. One supervisor addressed the “university and non-university divide,” and believed it would be “helpful to have working sessions with best practices, networking and an opportunity to plug in with other organizations.” These comments suggest that MSVP could operationalize as a network unto itself, providing a platform to transcend the community–campus divide under the auspices of national service.

During the interviews, supervisors requested resources from MSVP, such as model performance measures, survey templates, data collection tools, and technical assistance for VISTA members. This underscores the opportunity to leverage campus resources to support host sites. This became a two-way street when the supervisor at the afterschool program in the Delta offered to share readings the organization uses to orient new staff and volunteers about the history of civil rights struggles in Mississippi. Supervisors also provided feedback on reporting and aspects of the program prescribed by MSVP or AmeriCorps, and several campus-based supervisors emphasized the importance of aligning VISTA start dates with the academic calendar.

Inputs, Activities, and Outputs

The initial section of the proposed VISTA supervisor survey will inquire about service areas and organizational dynamics, including staffing, volunteers, reach, and funding. These questions will indicate baseline capacity to maximize the role of a VISTA. The activities section will mirror the work of Green (2013), with supervisors rating VISTA contributions to research, volunteer engagement, planning events and programs, communications, resource development, program evaluation, and partnership development. The outputs will align with the AmeriCorps performance measurements for capacity building.

Outcomes

The outcomes section will help identify longer-term changes that result from VISTA member activities. The following statements are drawn from the interview findings and address organizational development, scope, and reach due to the VISTA partnership. Supervisors will indicate their agreement with a series of statements and provide optional supporting narratives:

- My organization is more visible to the community as a result of this partnership.

- My organization is more visible to the university as a result of this partnership.

- My organization has additional credibility as a result of this partnership.

- My organization has formalized processes and procedures as a result of this partnership.

- My organization has increased its ability to conduct research as a result of this partnership.

- My organization receives additional requests for service as a result of this partnership.

- My organization has expanded its fundraising base as a result of this partnership.

- My organization has created new programming as a result of this partnership.

- My organization has completed additional projects as a result of this partnership.

- The VISTA member has been able to learn and grow as a result of my supervision and my organization’s role in this partnership.

These statements evoke an ideal scenario, in which an individual VISTA member’s growth influences organizational development and supervisors serve as a gateway to unlocking this potential.

Process Dimensions

The dimensions of process are drawn from the literature on community–campus partnerships and the interview findings. The following statements were crafted to cohere with the final theme of Dimensions of Alignment, signaling partnership reciprocity. In this final section, supervisors will note their agreement with the following statements and provide an optional supporting explanation:

- My organization has strong mission alignment with our campus partner(s) (Bringle et al., 2009).

- My organization and our campus partner(s) have common goals (Bringle et al. 2009).

- I feel a sense of investment in the strength and success of the MSVP network.

- The support that my organization receives from MSVP makes a positive impact on our work.

- The amount of time invested in the community–campus partnership is worth the results (Gazley et al., 2013; Srinivas et al., 2015).

- My organization has developed additional connections on campus (Srinivas et al., 2015)

- Decision making is shared equitably between my organization and our campus partners (Bringle & Hatcher, 2002; Schulz et al., 2003; Sandmann et al., 2014).

- My organization and the campus partner are working with shared resources (Bringle et al., 2009).

- Sufficient planning has been devoted to this community–campus partnership (Bringle et al., 2009).

- I have the opportunity to evaluate the VISTA’s work in a meaningful way (Gazley et al., 2013; Petri, 2015; Sandy & Holland, 2006).

- I believe that this community–campus partnership will be sustainable over time.

- If I had it to do all over again, I would pursue this community–university partnership (Srinivas et al., 2015).

These statements address process dimensions that reach for reciprocity, shared resources, and common goals. While there is power inherent in MSU sponsoring MSVP and selecting VISTA partner sites, eliciting supervisor feedback on the partnership process can shift the program toward greater equity by elevating supervisor concerns and perspectives.

Limitations

As a community engagement program housed at a university, MSVP offers lessons for higher education, with the caveat that VISTA members are not students. While some members of MSVP are recent college graduates, others are retirees or community members seeking a career change. The lessons from MSVP can be applied to community engagement insofar as they pertain to intensive capacity-building activities carried over a calendar year.

It is also important to note that nearly half of respondents represented campus-based supervisors extending community engagement activities through MSVP. These insights, however, illuminate an institutionalization process at MSU which contributed to a successful application for the 2020 Carnegie Community Engagement Classification, a competitive designation based on data collection and institutional practices that contribute to the public good (Public Purpose Institute, 2021).

Conclusion

A resource-scarcity mindset can pervade places that contend with persistent poverty. VISTA can help reframe that narrative by emphasizing capacity building—doing more in partnership than any organization can do in isolation. VISTA can be a powerful tool for colleges and universities working to institutionalize their community engagement missions while strengthening the operations of community partner organizations. Doing so while elevating the voice of community partners can ensure that these efforts attend to partnership process, mission alignment, and reciprocity.

MSVP uses VISTA supervisor interview findings to create an evaluation plan to understand dimensions of capacity building and partnership process through the project. A logic model provides a useful frame for organizing organizational resources, VISTA activities, and AmeriCorps performance measures with dimensions of partnership process and mission alignment. The data surface an important dialectic raised by VISTA supervisors: the promise of a new colleague at an understaffed organization versus the burden of actively supervising that VISTA member. This underscores the value of time as a precious commodity at nonprofit organizations and parallels findings around the burden of supervision for service-learning courses (Clayton et al., 2010; Littlepage et al., 2012). While a VISTA member can bring tremendous resources to an organization, sustaining a capacity boost remains a challenge.

MSVP holds great promise as a network: Supervisors on and off campus acknowledge the community–campus divide, despite their aligned missions. MSVP can help bridge that divide, both in the form of campus-based outreach driven by VISTA members as well as network facilitation by the Center for Community Engagement.

References

Adams, K. R. (2014). The exploration of community boundary spanners in university–

community partnerships. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 18(3), 113–118. https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/1140/1139

AmeriCorps. (2019). CNCS performance measures: AmeriCorps VISTA, FY 2019–2020. https://www.nationalservice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/VISTAPMInstructions_2019_010319_508.pdf

AmeriCorps. (2021). AmeriCorps VISTA annual program guidance for current and potential project sponsors: Fiscal Year 2022. https://www.americorps.gov/sites/default/files/document/2021_09_03_FY22%20AmeriCorps%20VISTA%20Annual%20Guidance_VISTA_0.pdf

Bass, M. (2013). The politics and civics of national service: Lessons from the Civilian Conservation Corps, VISTA, and AmeriCorps. Brookings Institution Press.

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (2002). Campus–community partnerships: The terms of engagement. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 503–516. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slcepartnerships/23

Bringle, R. G., Clayton, P. H., & Price, M. (2009). Partnerships in service learning and civic engagement. Partnerships: A Journal of Service Learning & Civic Engagement, 1(1), 1–20. http://libjournal.uncg.edu/prt/article/view/415

Clayton, P. H., Bringle, R. G., Senor, B., Huq, J., & Morrison, M. (2010). Differentiating and assessing relationships in service-learning and civic engagement: Exploitative, transactional, or transformational. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 16(2), 5–21. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0016.201

Cohodas, N. (1997). The band played Dixie: Race and the liberal conscience at Ole Miss. The Free Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications.

Cruz, N. I., & Giles, D. E. (2000). Where’s the community in service-learning research? Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7(1), 28–34. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.spec.104

Dempsey, S. E. (2010). Critiquing community engagement. Management Communication Quarterly, 24(3), 359–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318909352247

De Vita, C. J., Fleming, C., & Twombly, E. C. (2001). Building capacity in nonprofit organizations. Urban Institute. http://research.urban.org/UploadedPDF/building_capacity.PDF?q=capacity#page=10

Duncan, C. M. (2014). Worlds apart: Poverty and politics in rural America. Yale University Press.

Eagles, C. W. (2009). The price of defiance: James Meredith and the integration of Ole Miss. University of North Carolina Press.

Enos, S., & Morton, K. (2003). Developing a theory and practice of campus–community partnerships. In B. Jacoby and Associates (Eds.), Building partnerships for service-learning (pp. 20–41). Jossey-Bass.

Gazley, B., Bennett, T. A., & Littlepage, L. (2013). Achieving the partnership principle in experiential learning: The nonprofit perspective. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19(3), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2013.12001751

Green, J. J. (2013). Mississippi community service initiatives research project: Research and evaluation to inform community–campus partnerships [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Mississippi.

Grisham, V., & Gurwitt, R. (1999). Hand in hand: Community and economic development in Tupelo. https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/images/csg/Resource%20Hand%20in%20Hand%20Tupelo%20Story.pdf

Hycner, R. H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies, 8(3), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00142995

Kellogg Foundation (2004). W.K. Kellogg Foundation logic model development guide. https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resources/2004/01/logic-model-development-guide

Kindred, J., & Petrescu, C. (2015). Expectations versus reality in a university–community partnership: A case study. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(3), 823–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9471-0

Leiderman, S., Furco, A., Zapf, J., & Goss, M. (2002). Building partnerships with college campuses: Community perspectives. Council of Independent Colleges.

Littlepage, L., Gazley, B., & Bennett, T. A. (2012). Service learning from the supply side: Community capacity to engage students. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(3), 305–320. https://hdl.handle.net/2450/5845

McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R., & Allen, A. (2009). Brokering community–university engagement. Innovative Higher Education, 33(5), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-008-9086-8

Myers Asch, C. (2008). The senator and the sharecropper: The freedom struggles of James O. Eastland and Fannie Lou Hamer. University of North Carolina Press.

Petri, A. (2015). Service-learning from the perspective of community organizations. Journal of Public Scholarship in Higher Education, 5, 93–110. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1120304.pdf

Public Purpose Institute (2021). Community engagement classification. Retrieved from: https://public-purpose.org/initiatives/carnegie-elective-classifications/community-engagement-classification-u-s/

Sandmann, L. R., Jordan, J. W., Mull, C. D., & Valentine, T. (2014). Measuring boundary-spanning behaviors in community engagement. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 18(3), 83–96. https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/1137/1136

Sandy, M., & Holland, B. A. (2006). Different worlds and common ground: Community partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13(1), 30–43. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ843845.pdf

Schulz, A. J., Israel, B. A., & Lantz, P. (2003). Instrument for evaluating dimensions of group dynamics within community-based participatory research partnerships. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00029-6

Srinivas, T., Meenan, C. E., Drogin, E., & DePrince, A. P. (2015). Development of the community impact scale measuring community organization perceptions of partnership benefits and costs. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 21(2), 5–21. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0021.201

Stoecker, R., Tryon, E. A., & Hilgendorf, A. (Eds.). (2009). The unheard voices: Community organizations and service learning. Temple University Press.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American journal of evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Tinkler, A., Tinkler, B., Hausman, E., & Tufo-Strouse, G. (2014). Key elements of effective

service-learning partnerships from the perspective of community partners. Partnerships: A Journal of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement, 5(2), 137–152.

Weerts, D. J., & Sandmann, L. R. (2008). Building a two-way street: Challenges and opportunities for community engagement at research universities. The Review of Higher Education, 32(1), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.0.0027

Appendix: Interview Protocol for VISTA Supervisors and Members to Assess the Community Impact of MSVP

VISTA Supervisor Interview Questions

Introductory Questions / Checking In

- What was your initial expectation of how a VISTA would contribute to your organization?

- How is the VISTA term going so far? What are some successes you have had?

- What are some challenges you have faced in working with a VISTA and/or MSVP? (Probes: time constraints of VISTA term, time commitment to VISTA, trust/confidence in VISTA, supervision challenges, resources required for VISTA, training/orientation of VISTA, communication with MSVP.)

Mission Alignment and Impact

- To what extent does the VISTA member demonstrate a connection to the national service movement?

- How does the Mid-South VISTA Project’s mission align with your organization’s mission? How does the VISTA’s role impact that connection?

- What benefits has the VISTA produced for your organization? (Probes: increased visibility/awareness, resource development, etc.)

Workplace

- What challenges, if any, have you encountered in training and supervising the VISTA? (Probes: Is the expectation that supervisors devote 10% of their time to supervision too burdensome? Has the VISTA required additional training to fulfill the requirements of the VAD?)

- How do you ensure that the VISTA member is staying focused on the VISTA Assignment Description (VAD) and not displacing the work of staff members?

- How are you integrating the VISTA member into your staff?

MSVP Partnership

- What improvements can be made to the reporting mechanisms for the VISTA (i.e. timesheets and monthly reporting)?

- How would you characterize the support that you receive from MSVP? What additional support do you need?

- How can the Center for Community Engagement improve partnerships and strengthen the MSVP network?

- Have there been other outcomes of this partnership for your organization not captured in the questions above?

Author

Dr. Laura Martin brings nearly 15 years of experience working on poverty alleviation programs at the grassroots and public policy levels. After college, she facilitated service-learning trips and managed a community development project in rural Nicaragua. Most recently, Laura worked as a Policy and Research Coordinator at the Texas Association of Community Health Centers, where she analyzed legislation and regulations impacting health centers, and coordinated trainings for a federal grant to conduct CHIP and Medicaid outreach and enrollment in the Rio Grande Valley. As Legislative Director for Texas State Representative Armando Walle, Dr. Martin developed legislation regarding juvenile justice and stemming the high school dropout rate.

Dr. Laura Martin brings nearly 15 years of experience working on poverty alleviation programs at the grassroots and public policy levels. After college, she facilitated service-learning trips and managed a community development project in rural Nicaragua. Most recently, Laura worked as a Policy and Research Coordinator at the Texas Association of Community Health Centers, where she analyzed legislation and regulations impacting health centers, and coordinated trainings for a federal grant to conduct CHIP and Medicaid outreach and enrollment in the Rio Grande Valley. As Legislative Director for Texas State Representative Armando Walle, Dr. Martin developed legislation regarding juvenile justice and stemming the high school dropout rate.

At the McLean Institute, Dr. Martin works to engage faculty, staff, students, and community partners in mutually beneficial efforts to improve quality of life in Mississippi. She directs M Partner, a university-wide community engagement initiative, and supervises staff and graduate assistants leading the North Mississippi VISTA Project.

Dr. Martin holds dual undergraduate degrees in Hispanic Studies and International Relations from Brown University, where she graduated with honors. Additionally, she holds a Master of Public Affairs degree from the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where she completed a Portfolio Program in Nonprofit and Philanthropic Studies, and a Doctorate of Higher Education from the University of Mississippi.