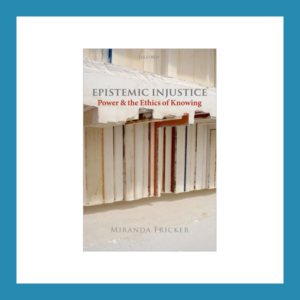

Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing, by Miranda Fricker. New York: Oxford University Press. August 2007. ISBN: 9780198237907. 192 pages.

Author Note

Star Plaxton-Moore, Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, University of San Francisco.

Correspondence regarding this book review should be addressed to Star Plaxton-Moore, Director of Community-Engaged Learning, Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, University of San Francisco, 2130 Fulton Street, San Francisco, CA 94117-1080. Phone: (415) 422-2156. Email: smoore3@usfca.edu

Since November 2018, my colleagues and I at the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good at the University of San Francisco have been working with a few long-time community partners to update our professional development curriculum. Our efforts led recently to the launch of the Community Partner Co-Educator Fellowship, a series of six 2-hour workshops designed to deepen nonprofit staff members’ understanding of community-engaged learning and to develop practices for cultivating reciprocal partnerships and fostering students’ civic learning. As we moved through the program design process, we were committed to integrating community voices into this fellowship, but we struggled to find publications that emanated purely from community expertise. Though community partners have participated in some qualitative studies, their voices are often shared by researchers as short quotes to illustrate overarching themes (Bacon, 2002; Blouin & Perry, 2009; Cronley, Madden, & Davis, 2015; Sandy, 2007; Sandy & Holland, 2006; Tinkler, Tinkler, Hausman, & Tufo-Strouse, 2014; Worrall, 2007). In fact, we could only find one peer-reviewed article authored by a community partner (Reyes, 2016). Is it truly the case that so few resources reflect the perspectives of those community-based wisdom-holders meant to be collaborators in the work of community-engaged learning?

Knowing that peer-reviewed journals were designed as competitive outlets for scholars to share their knowledge in a rigidly defined written format, we asked: What other resources might be more accessible for community partner voices to permeate the field of community engagement? At the McCarthy Center, our strategy for including community partner voices has involved inviting (and compensating) partners as guest lecturers, panelists, committee members, and contributors to outreach and orientation media. However, while we have found a way to invite these voices into our institution, it seems that the broader field still fails to honor the reciprocal exchange of knowledge needed to create new knowledge with community partners.

This particular gap in the community engagement literature highlights myriad questions that I have wrestled with in my 14 years as a community engagement professional, and I know many others are asking and attempting to answer similar questions. Indeed, I believe it is our responsibility as community engagement scholars and practitioners to explore such questions as:

- If we look to the literature on community engagement, whose voices shape the field, and whose voices are missing or on the margin?

- How is knowledge actually exchanged across campus-community boundaries, and how is that knowledge used and valued?

- To what extent are community partners positioned as co-educators of students and collaborators in scholarship and research?

- In what ways are students’ various learning styles, strengths, and limitations accommodated in community-engaged courses, and how are they encouraged to demonstrate learning beyond the creation of traditional work products?

- How are faculty recognized and rewarded for teaching and scholarship that emanate from a commitment to creating community change?

I have found the framework of “epistemic in/justice”—described in Miranda Fricker’s Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing—to be useful in analyzing these big, complex questions about the limitations and aspirations of higher education community engagement. I have had the privilege of working with colleagues from institutions across the United States and with our community partners to apply and adapt this framework in professional development venues and in the literature. (To learn more about this ongoing project, please visit https://epistemicjusticeiarslce2018.wordpress.com/.) Indeed, I see this book review as one more opportunity to enliven and extend critical conversations about higher education community engagement.

In order to situate an examination of community engagement in light of the epistemic in/justice framework, I think it is helpful to briefly zoom out to acknowledge the higher education context. Higher education originated as a bastion for the production and dissemination of elite knowledge for the primary benefit of wealthy White men. Though today’s colleges and universities have become far more accessible for students and faculty across diverse genders, races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic statuses, the legacy of elitism and exclusion within higher education continues to shape what knowledge is valued, shared, and celebrated. Looking to the discipline of philosophy as an example, one finds that, as of 2015, only 13% of authors of articles in the top five philosophy journals were women (Schwitzgebel, 2015), and between 2003 and 2012, only .32% of authors featured in the top 15 philosophy journals identified as Black (Bright, 2016). Further, as of 2014, women made up only 10% of the 267 most cited contemporary authors in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and only 3% of cited authors identified as people of color (Schwitzgebel, 2014). These statistics indicate a lack of diversity in the epistemological content of higher education texts, even as faculty and student demographics have become more diverse. To be fair, this problem pervades most academic disciplines. Scholars have argued that underrepresentation of women and people of color in top-tier publications is due to myriad factors, including implicit bias and stereotype threat (Saul, 2013). Implicit bias shapes how scholars and editors select publications to be featured, and stereotype threat prevents people from underrepresented groups from pursuing particular career paths and practices that are not traditionally seen as inclusive.

The previous publication and citation statistics illustrate that identity-based bias blocks collective access to valuable knowledge because certain groups of people are left out of the academic conversation. However, given that the central mission of academia is to produce and disseminate knowledge, scholars and practitioners have an obligation to take issues of epistemic exclusion seriously and seek proactive approaches to ensuring equity and inclusion of diverse forms of knowledge. Moreover, because exclusion of certain types of knowledge is based on dominant conceptions of which types of knowledge are valuable, and because these conceptions are inextricably linked to aspects of scholars’ identities, the imperative to address this injustice is also an ethical one. How does one attend to the epistemic and ethical harms that have been baked into higher education since its inception?

Enter Fricker’s work on epistemic injustice, which focuses on the manifestation of injustice in two everyday human practices: conveying knowledge and making sense of experience. From this starting point, Fricker diagnoses how identity-based power and prejudice harm individuals in their capacities as knowers, and keep them from accessing essential truths about human experience. She then offers practical approaches for building individuals’ capacity to be more just in their epistemic interactions with others, and in their cultivation and stewardship of collective knowledge.

Though the concept of identity-based oppression is neither new in academe nor uniquely theorized in philosophy, Fricker’s analysis of identity-based oppression as having both ethical and intellectual dimensions warrants attention because it offers fresh insight into the multifaceted and cumulative nature of harms committed in daily communication and meaning-making. Drawing upon the work of critical social theorists, philosophers, and scholars, including Iris Marion Young (1992), Fricker posits that epistemic injustice is one facet of the status quo of identity-based domination and highlights many examples of how it plays out in casual social situations as well as high-stakes contexts like courtrooms and classrooms. In essence, epistemic injustice manifests as the exclusion of people with marginalized identities from (1) being heard and understood by others in interpersonal communications (i.e., testimonial injustice), and (2) contributing to broader and deeper social understandings of the human experience (i.e., hermeneutical injustice).

Fricker introduces testimonial injustice in the first chapter of Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing and elaborates on the nature and manifestations of the concept in Chapters 2 and 6. Testimonial injustice occurs interpersonally when the hearer/receiver of knowledge allows identity prejudice to undermine the credibility of the speaker/knowledge-holder. The result is a dysfunction in knowledge dissemination that leads simultaneously to three types of harm. Epistemic harm results when important knowledge is not integrated into the hearer’s understanding, meaning untruth is perpetuated to the detriment of both the immediate discussion parties and potentially others to whom they transmit knowledge. Ethical harm results when the knower’s knowledge is devalued and, because knowledge transmission is an essential aspect of what it means to be human, their humanity is degraded. The cumulative effect can be a growing sense of self-doubt that inhibits the knower’s participation in social interactions. Practical harm results from dysfunctional knowledge transmission that shapes actions and events to exclude, censure, or dismiss the knower. As an example of this harm, Fricker highlights the instance of an individual’s self-defense testimonial not being believed by a judge or jury, resulting in jail time.

In the context of a service-learning course, practical harm might manifest in the experiences of low-income students who must prioritize paid work over service activities connected to their course in order to maintain financial stability. When the student approaches their instructor to express concern about schedule conflicts and articulate the need to maximize paid work hours, the instructor may dismiss these concerns as the student not having their priorities straight or as if they are trying to get out of course assignments. Instead of validating the student’s assessment of their own situation and working with them to come up with alternative ways to fulfill the community-engaged component of the course, the instructor adopts a hard line, forcing the student to choose between a passing grade and financial stability. While this may happen in interpersonal interactions within discreet service-learning classrooms, scholars have also pointed to this as a systemic issue related to service-learning not being designed to include and accommodate low-income students (Butin, 2006; Cruz, 1990; Mitchell, 2014), thereby exemplifying hermeneutical injustice.

Fricker describes hermeneutical injustice in the culminating chapter of the book (Chapter 7). Whereas testimonial injustice plays out at the interpersonal level, hermeneutical injustice occurs at the systemic level through identity-based marginalization, keeping whole groups of knowers from participating in shaping social understandings of the human experience. Society excludes groups either because the knowledge they hold does not comport with the dominant worldview—and therefore cannot be understood using existing cognitive frames—or because marginalized peoples’ methods of expressing certain kinds of knowledge are not accepted as legitimate by the dominant culture. Fricker uses the example of how women were historically confined to their households, limited to discussing what was deemed polite or appropriate and labeled as non-rational, emotionally-driven beings in an effort to prevent them from generating a collective understanding of their experiences of gender-based oppression and acting against it. Experiences of post-partum depression or domestic violence were common and consequential, but they were not identified or addressed until somewhat recently in human history because of systems and structures excluding women as valid knowledge producers and disseminators. Similar to the impacts of testimonial injustice, the harms of hermeneutical injustice have implications for emotional and psychological well-being, but also for social and economic status. Because of the systemic nature of hermeneutical injustice, the harms impact entire identity-based groups.

Extrapolating this phenomenon to the experiences of faculty in higher education highlights how community-engaged scholarship continues to be marginalized in high-stakes tenure and promotion review processes. Though not necessarily defined as an identity-based group, many community-engaged scholars are faculty of color and women (Evans, Taylor, Dunlap, & Miller, 2009; Sturm, Eatman, Saltmarsh, & Bush, 2011). These scholars have professional commitments, engage in pedagogical practices, and disseminate scholarly products that emanate from engagement with community (e.g., teaching service-learning courses, conducting community-based participatory research, etc.). Their scholarly work is grounded in transdisciplinary conceptions of knowledge (i.e., knowledge that transcends disciplines and the campus) and is characterized by asset-based qualities of reciprocity, mutual respect, shared authority, and co-creation of goals and outcomes. This orientation to knowledge and scholarship leaves them occupying the margins of what is traditionally accepted in terms of teaching, research, and service. Thus, there is a high likelihood that their faculty peers (who do not do community-engaged teaching and research) may misunderstand, distrust, or devalue the work products and narratives they present in their dossiers. It is common for community-engaged scholarship to be deemed less rigorous and less valuable than traditional positivist approaches, which prioritize pure research methodologies and the discovery of new knowledge (Eatman et al., 2018). One reason for the persistence of this problem is the gap in knowledge about how to properly define and assess high-quality community-engaged scholarship. Though guidelines and standards exist (Jordan et al., 2009), they have not been widely adopted across colleges and universities. Therefore, faculty members who “communicate” with the world through community-engaged practices may find themselves to be misunderstood within the dominant cognitive constructs of what constitutes high-quality faculty performance and therefore not selected for tenure or promotion.

Fricker also illuminates examples of what is possible when typically marginalized knowers are heard and understood by those in power. In Chapters 3 and 4, she places the onus on individuals to cultivate a practice of reflection and analysis when taking on the role of knowledge-receivers, such that they can intentionally subvert their prejudicial tendencies from impeding epistemic and ethical connections to knowledge-givers. Doing this facilitates testimonial justice, which occurs when knowledge is communicated interpersonally, unfettered by identity-based bias, in a way that affirms the credibility (and by extension the humanity) of the knower and builds the understanding of the knowledge-receiver. In Chapter 5, Fricker discusses the genealogy of testimonial injustice, referencing foundational philosophical theories and concepts to situate her framework in the broader field. In particular, she describes the “state of nature,” as imagined by Williams (2002) and Craig (1990), as the condition for the inevitable emergence of identity-based prejudice (a pre-cursor to testimonial injustice). She also highlights virtues of truth, accuracy, and sincerity as necessary for humans to be able to overcome identity-based prejudice in order to effectively pool knowledge necessary for human survival.

As an antidote to hermeneutic injustice, Fricker, at the end of Chapter 7, provides only a brushstroke of her vision of hermeneutical justice. Individuals enact hermeneutical justice as a corrective virtue by displaying context-sensitive judgment in their interactions, recognizing that their lack of understanding in response to another’s testimony may be a result of systems of knowledge that delegitimize certain ways of knowing, and not a deficiency within the speaker, and potentially taking responsibility for seeking additional evidence in support of the speaker’s testimony. Writ large, hermeneutical justice occurs when society holds space for and values diverse ways of making sense of the human experience.

Considering the frequency and scale of interpersonal knowledge exchange in society, Epistemic Injustice has significant ramifications for transforming identity-based oppression. Fricker offers a coherent theory for a very particular, but common, human experience of identity-based injustice and a useful prescription for correcting it. Fricker is not the first or only scholar to name and describe the phenomenon of power relations inhibiting particular people’s opportunities to participate fully in society and how to address it. Indeed, she references a number of scholars in other fields who have offered theoretical frameworks for exposing and interrogating unjust actions and systems. Rather, Fricker’s framework is a worthy addition to the myriad bodies of theory that transcend purely disciplinary and scholarly application to help individuals analyze and ultimately dismantle oppression in practice. In making the case that exchanges of knowledge are fundamental to what it means to be human and to be part of society, and then connecting the inhibition of knowledge exchange to intellectual, ethical, and practical harms, Fricker makes a strong argument for why all people should care about and bear responsibility for creating a more epistemically just world. Further, Fricker fosters optimism that change is possible by suggesting how one might grow one’s capacities for being a more virtuous knowledge-receiver and ultimately galvanize others to elevate this practice to the level of hermeneutical transformation.

As someone who does not have a scholarly background in philosophy but who is immersed in the culture of academia, I found this book to be compelling and accessible. Fricker offers clear and well-reasoned definitions of complex concepts and illustrates them with multiple practical examples. Further, she explicitly renders the relationships between the theoretical components of her argument into a comprehensive framework. I admit that I struggled somewhat with the chapters on the “Genealogy of Testimonial Injustice” and “Original Significances” because of my lack of familiarity with foundational philosophical canons, but I was still able to glean the essential arguments from both chapters.

For readers operating in a higher education context, where the creation, synthesis, application, and dissemination of knowledge are core functions, and where dominant cultural norms shape everything from student admissions to faculty tenure and review policies, Fricker’s text provides both an ethical imperative and a framework for how we, as professionals within that context, might transform our institutions to be more epistemically just. If we mean to be virtuous in our individual dealings as professionals and participate in virtuous institutions, then we would do well to reflect upon the following questions in light of Fricker’s theory and act in accordance with her prescriptions: How can we create space for students, faculty, and staff to demonstrate and disseminate knowledge in diverse ways? How can we design courses that benefit from the diversity of epistemic traditions? How can we provide faculty development opportunities that build capacity to enact epistemic justice in teaching, advising, research, and service? What skills and information do students need to prepare to engage ethically across epistemic differences in the higher education context and beyond? To what extent are the voices of diverse staff, faculty, and students able to guide institutional agendas and priorities? What institutional values and virtues are likely to foster epistemic justice in how policies and practices are designed and implemented?

Zeroing in on the practice of community engagement in higher education, implementation of an epistemically just framework becomes even more imperative because of the relational nature of the work (both at the interpersonal and institutional levels) and its focus on employing knowledge to address contemporary social and environmental problems. If we as community-engaged scholars and practitioners believe that the condition of epistemic injustice is the status quo, as Fricker asserts, then it follows that we are likely to cause harm by conducting business as usual. By drawing exclusively on existing bodies of academically legitimate knowledge to guide our understandings of justice issues, and by employing traditional positivist and extractivist methods to guide community interventions, we might easily reinforce neo-colonial dynamics between “town and gown.” On the other hand, community engagement holds great potential as an incubator for higher education’s burgeoning efforts to diversify its epistemological universe. Under the rubric of community engagement, pedagogical frames are rooted in a desire to democratize the exchange of knowledge in and out of the classroom, and research methodologies are participatory, oriented toward addressing community-identified problems.

Given this, our call to action as community-engaged scholars and practitioners is to strive for greater alignment between the aspirational vision for community engagement and practice. What changes are needed for community engagement processes, practices, and policies to reflect equitable participation of diverse constituencies? How can the outcomes of this work achieve epistemic justice by perpetuating more nuanced understandings of both universal and unique aspects of the human condition? What commitment can we make to demonstrate humility, intellectual curiosity, and empathy in our daily interactions? In which situations might we abdicate our roles as experts when working with community in order to amplify voices of expertise and wisdom not traditionally legitimized in academia? How might we create space for students to grapple with their own limitations and aspirations as they navigate community-engaged experiences? How do we infuse the virtue of epistemic justice into the culture of our community-engaged departments and centers? I suggest boldly that, armed with frameworks like Fricker’s, we draw closer to answering these questions and achieving a more epistemically just vision for our work.

References

Bacon, N. (2002). Differences in faculty and community partners’ theories of learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9(1), 34–44.

Blouin, D. D., & Perry, E. M. (2009). Whom does service learning really serve? Community-based organizations’ perspectives on service learning. Teaching Sociology, 37(2), 120–135.

Bright, L. K. (2016). Publications by Black authors in Leiter top 15 journals 2003-2012 [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2016/01/publications-by-black-authors-in-leiter.html

Butin, D. W. (2006). The limits of service-learning in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 29(4), 473–498.

Craig, E. (1990). Knowledge and the state of nature: An essay in conceptual synthesis. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Cronley, C., Madden, E., & Davis, J. B. (2015). Making service-learning partnerships work: Listening and responding to community partners. Journal of Community Practice, 23(2), 274–289.

Cruz, N. (1990). Principles of good practice in combining service and learning: A diversity perspective. St. Paul, MN: Author.

Eatman, T. K., Ivory, G., Saltmarsh, J., Middleton, M., Wittman, A., & Dolgon, C. (2018). Co-constructing knowledge spheres in the academy: Developing frameworks and tools for advancing publicly engaged scholarship. Urban Education, 53(4), 532–561.

Evans, S. Y., Taylor, C. M., Dunlap, M. R., & Miller, D. S. (Eds.). (2009). African Americans and community engagement in higher education: Community service, service-learning, and community-based research. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Jordan, C., Wong, K., Jungnickel, P., Joosten, Y., Leugers, R., & Shields, S. (2009). The community-engaged scholarship review, promotion, and tenure package: A guide for faculty and committee members. Metropolitan Universities, 20(2), 66–86.

Mitchell, T. D. (2014) Structures of inclusion: Lynton Colloquium [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCFKZvf8nFI

Reyes, R. (2016). Engaged pedagogy: Reflections from a Barriologist. Engaging Pedagogies in Catholic Higher Education, 2(1), Article 1.

Sandy, M. (2007). Community voices: A California Campus Compact study on partnerships. San Francisco, CA: California Campus Compact

Sandy, M., & Holland, B. A. (2006). Different worlds and common ground: Community partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13(1), 30–43.

Schwitzgebel, E. (2014). Citation of women and ethnic minorities in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2014/ 08/citation-of-women-and-ethnic-minorities.html

Schwitzgebel, E. (2015). Only 13% of authors in five leading philosophy journals are women [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2015/12/only-13-of-authors-in-five-leading.html

Saul, J. (2013). Implicit bias, stereotype threat and women in philosophy. In F. Jenkins & K. Hutchison (Eds.), Women in philosophy: What needs to change? (pp. 39–60). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sturm, S., Eatman, T., Saltmarsh, J., & Bush, A. (2011). Full participation: Building the architecture for diversity and public engagement in higher education (White paper). New York, NY: Columbia University Law School, Center for Institutional and Social Change.

Tinkler, A., Tinkler, B., Hausman, E., & Tufo-Strouse, G. (2014). Key elements of effective service-learning partnerships from the perspective of community partners. Partnerships: A Journal of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement, 5(2), 137–152.

Williams, B. A. O. (2002). Truth and truthfulness: An essay in genealogy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Worrall, L. (2007). Asking the community: A case study of community partner perspectives. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(1), 5–17.

Young, I. M. (1992). Five faces of oppression. In T. Wartenberg (Ed.), Rethinking power (pp. 174–195). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Author

Star Plaxton-Moore is the Director of Community-Engaged Learning at the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good at the University of San Francisco. Star directs institutional support for community-engaged courses and oversees public service programs for undergraduates, including the Public Service and Community Engagement Minor. She designed and implements an annual Community-Engaged Learning and Teaching Fellowship program for USF faculty, as well as other professional development offerings that bring together faculty and community partners as co-learners. Her scholarship focuses on faculty development for community-engaged teaching and scholarship, student preparation for community engagement, assessment of civic learning outcomes, and community engagement in institutional culture and practice. Star holds an MEd from George Washington University and is currently completing course work for an EdD in organizational leadership at USF.

Star Plaxton-Moore is the Director of Community-Engaged Learning at the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good at the University of San Francisco. Star directs institutional support for community-engaged courses and oversees public service programs for undergraduates, including the Public Service and Community Engagement Minor. She designed and implements an annual Community-Engaged Learning and Teaching Fellowship program for USF faculty, as well as other professional development offerings that bring together faculty and community partners as co-learners. Her scholarship focuses on faculty development for community-engaged teaching and scholarship, student preparation for community engagement, assessment of civic learning outcomes, and community engagement in institutional culture and practice. Star holds an MEd from George Washington University and is currently completing course work for an EdD in organizational leadership at USF.