Abstract

The societal struggles in American higher education have intensified in recent years, impacting various facets of academic life. Enrollment declines, rising costs, student debt, and emerging alternatives pose significant threats to colleges and universities. The COVID-19 pandemic further strained institutions, leading to deeper budget cuts and potential closures.

Falling tuition revenue coupled with culture wars and political polarization have led to prolonged institutional trauma in higher education institutions. Conservative-leaning states have restricted faculty tenure, courses dealing with social and political inequity, and DEI initiatives, while progressives emphasize universities’ role in fostering critical thinking and truth.

Organizational trauma can significantly impact an organization’s well-being. It can arise from a single catastrophic event or persistent issues such as workplace biases, discrimination, and poor communication. For many campuses, this manifests as chronic stress, apathy, and mental health challenges, leading to turnover of faculty and staff and low productivity. Understanding and addressing organizational trauma is crucial. Strategies include fostering resilience through supportive leadership, trust-building, and inclusive practices.

Thoughtful solutions and collective efforts are needed to heal and strengthen American democracy. The 2024 elections remain uncertain, raising questions about the future of not only higher education, but American democracy. Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to bridge divides, promote critical thinking, and uphold the purpose of higher education. The path forward remains complex, but collective action is essential to repair and strengthen American civic health.

Introduction

Like most institutions in this country, Western Kentucky University (WKU)—a public, midsized regional comprehensive institution—has hit some rough patches over the past 10 years. WKU has endured cuts to state budget allocations, massive turnovers in senior leadership, and decreases in enrollment across the board. Additionally, the proposal of state legislation across the country which could impact faculty tenure, annihilate DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) initiatives, and change performance-based funding models has sparked sweeping, intense debates and concerns about autonomy and government overreach (Goldman, 2024; Horsley, 2024). Furthermore, these pieces of legislation reflect broader societal debates about the purpose and direction of higher education in the “court of public opinion.” It seems the polarization in the United States has impeded the consideration of long-term implications and muted engagement in thoughtful discussions to find balanced solutions.

A Campus Example

The story unfolds in mid-spring of 2024 after an announcement about an upcoming campus speaker spread across social media, eliciting a wide range of emotional responses. Although the university wasn’t directly sponsoring the speaking engagement, the campus and community erupted in outrage as the administration faced criticism for what was perceived as a “lack of action” and anticipation of the event mounted. WKU has hosted controversial speakers in the past and navigated numerous clashes of ideologies, dissent, and impassioned debates that challenge the foundations of the First Amendment; however, this time felt distinctly different. As the event date neared, discussions grew more intense. Some advocated for First Amendment rights, emphasizing the value of diverse perspectives. Meanwhile, others worried about potential harm the speaker’s viewpoints may have on historically marginalized populations. The campus buzzed with anticipation, uncertainty, and a sense that this event would have a lasting impact on our campus.

On the night of the event, WKU’s Emergency Operations Team—comprised of police, emergency responders, communications personnel, and other campus administrators—carefully monitored both the event taking place in a small room within the student union and the counter-protests by community and campus members outside the venue. Their objective was to detect any potential confrontations within the crowds and prevent them from escalating. As the team watched the events unfold, a single question silently loomed in the air: How much more can we endure? The collective psyche of everyone involved that evening bore the scars of the turmoil the campus has faced over the past few years—a testament to the relentless challenges that weighed heavy on the campus. It was more than individual exhaustion; it was shared organizational trauma. Ultimately, the speaker arrived, and the event proceeded without any incidents, thanks to the excellent work of the leadership team before and during the speaking engagement. The aftermath has been negligible, but reflections on the boundaries of freedom of expression, the role of universities in fostering dialogue, the proper conduits of communication, and the responsibility to protect against harm still linger—a reminder that, even among the smallest of ripples, there are forces that can reshape the landscape, resulting in continued trauma to the organization.

The weight of budget cuts, dwindling enrollments, COVID-19, and pending anti-DEI state legislation has slowly taken a toll on WKU’s once-vibrant spirit. On the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic and the night before the 2021 fall graduation, WKU also endured the devastation of an EF3 tornado that ripped through the city, including the WKU campus; the December 11, 2021 tornado ultimately killed 17 community members (Garcia, 2021; Ramsey, 2022). While no students were injured, the campus was shaken to the core by the destruction and loss to the community.

In addition, like many universities across the United States, WKU’s halls echo with whispered grievances that have been triggered by the loss of cherished programs, the fading vibrancy of our arts, and the hollowing of the university’s academic core. Each cut and each reduction have mounted until our way forward seems dim. Some faculty and staff cling to rhetoric associated with their memories of better days, others mount protests, but the majority just simply disappear. While campus leadership handled this crisis with expertise and grace, healing still must be done to restore the cherished spirt of the institution. There is no doubt that the 2024 election season (and election seasons going forward) will bring about continued disruption and division to campuses across the nation, including WKU. How leaders and administrators handle this divisiveness is crucial to the institution’s ability to move forward and thrive.

Organizational Trauma as a Construct

While faculty, staff, and students on college campuses are personally affected by catastrophic events in varying ways, many overlook the notion that traumatic experiences can impact institutions as a whole. Organizational trauma therefore refers to the collective impact of traumatic events on the entire system that can disrupt the internal and external core functions (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). The goal of the organization is to become resilient; the question is how can leaders help their organizations heal and grow? Just as childhood survivors can experience post-traumatic growth, organizations can also respond to trauma in ways that allow them to surpass the pre-trauma state (Alexander et al., 2021). This notion doesn’t minimize the suffering or psychological challenges that survivors encounter but taps into the potential resilience of the human spirit (Kaye-Tzadok & Icekson, 2022).

Organizational trauma refers to significant adverse events or experiences within an organizational context that profoundly affect the psychological well-being and functioning of individuals and the collective (Vivian & Hormann, 2015). Organizational trauma, distinct from cyclical change and crisis, resembles a natural disaster that disrupts members’ sense of the world and their collective place in it, leaving them temporarily vulnerable or even permanently damaged (Kramer et al., 2022). All organizations are subject to growth and change, such as planned adaptations to market shifts or the implementation of new technological software, but organizational crises are unforeseen events impacting the organization’s survival if not immediately remedied (Pearson & Clair, 1998). For example, the loss of a funding stream or beloved leader can lead to uncertainty. If not addressed, this uncertainty can result in long-term problems like systemic distrust, generalized apathy, and low employee morale.

Whether short or long term, traumas debilitate organizations. Organizational trauma can result from a single devastating incident like COVID-19 or persistent harms that occur due to workplace biases, discrimination, bullying, or lack of communication and transparency. (Cunningham & MacGregor, 2000; van Dijke & De Cremer, 2013). Systematic dysfunction, toxic culture, and ineffective leadership are almost always the root of organizational trauma (Lindsay, 2021; Hormann, 2017). For individual employees, this trauma may appear as chronic stress and other mental health issues. This psychological distress can lead to high turnover, chronic absenteeism, and low productivity. Organizational trauma not only serves as a major impediment to individual employee performance, but the organization’s comprehensive efficacy as well (Cooper, 2023). Understanding the nature and impact of organizational trauma is essential for implementing effective strategies to address and mitigate its consequences.

In recent years, the United States has experienced significant societal struggles that have fractured various aspects of American life and impacted higher education. The student loan debt burden has surged, racism and violence against people of color persist, social mobility is declining, income inequality is widening, and affordable housing remains a significant challenge (Danaby, et al., 2024; Kang, et al., 2024; Zeiders, et al., 2021). Political division has added to the crisis by exacerbating social tensions, hindering effective policy-making, and deepening mistrust of the government and public institutions. Additionally, the polarization of radical ideologies has led to social gridlock, making it challenging to address critical issues. These culture wars playing out on the national stage have had direct repercussions on higher education institutions as well. Conservative-leaning states have passed legislation to abolish tenure and promotion for faculty (Bauer-Wolf, 2023), restricted “controversial and divisive” courses, and dismantled university DEI initiatives (Gretzinger, et al., 2024). Progressives, however, view universities as essential drivers of societal change, emphasizing their role in fostering critical thinking and promoting truth. Any efforts to restrict what and how classes are taught undermine the sole purpose of higher education. Despite their differences, both conservatives and progressives recognize that the current political climate poses challenges to intellectual discourse. As a result, the rising tensions at the intersections of politics, culture, and academia have raised important ideological discussions about the directives of education and their impact on society.

Numerous campuses in Kentucky and across the country have endured challenges to freedom of speech, protests and counter-protests, and, more recently, pro-Palestinian encampments, all igniting doubts about campus management. The geopolitical Israel-Hamas war has found its way to both public and private universities across the nation. Pro-Palestinian activists demanding schools divest from companies who do business with Israel set up encampments at more than 70 campuses across the United States in the spring of 2024 (Kottke, 2024). The nationwide movement has led to clashes with police, confrontations with counter protesters, and frustrations about campus administrators’ management of the crises. At the same time, antisemitism has exponentially increased and violence against Jewish students has risen (Josef & Hagen, 2024). Attempts by university presidents to respond and mitigate the outrage were met with scrutiny, forced resignations, and threats of defunding from alumni and donors (Fischer, 2023). Media coverage of the five-hour congressional hearing where lawmakers pressed the presidents of Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, and MIT on the topic of antisemitism in December 2023 drew unprecedented public attention and discourse (Ma, 2023).

These situations remain complex as universities continue to navigate seemingly impossible challenges while balancing the rights of protesters and maintaining a safe and respectful environment for all members of their communities. These struggles underscore the need for thoughtful solutions and collective efforts to heal, repair, and strengthen American democracy. But is that possible? Will it ever get better? What does this mean for college and university campuses? Mounting political conflicts have compounded the complexity of campus dynamics and further strained efforts to maintain safe and respectful environments for all. Political and civic divide has found a stage and audience, once again, in educational institutions.

Through not a widely known concept, civic health is defined as “the ways in which residents of a community (or state) participate in activities that strengthen well being, enhance interconnections, build trust, help each other, talk about public issues and challenges, volunteer in government and non-profit organizations, stay informed about their communities, and participate directly in crafting solutions to various social and economic challenges”

(Moore-Vissing et al., 2023, p.5). While the authors discuss civic health in the context of the broader community, the same concept applies to organizations. Conflicts on college campuses, fueled by national crises, uniquely endanger the civic health of our institutions. Diminished efforts to promote civil discourse, classroom censorship, and internal conflicts between faculty and administration all threaten campus well-being. Despite varying circumstances, there are general best practices for restoring community and institutional health. Organizations can promote resilience by facilitating structures and processes and providing proactive, supportive, positive, and energetic leadership to promote resilience. Building a culture of trust and support are essential to mitigating organizational trauma. Intentional inclusive practices also serve to increase organizational resilience (Brown et al., 2021).

Risk and Resilience

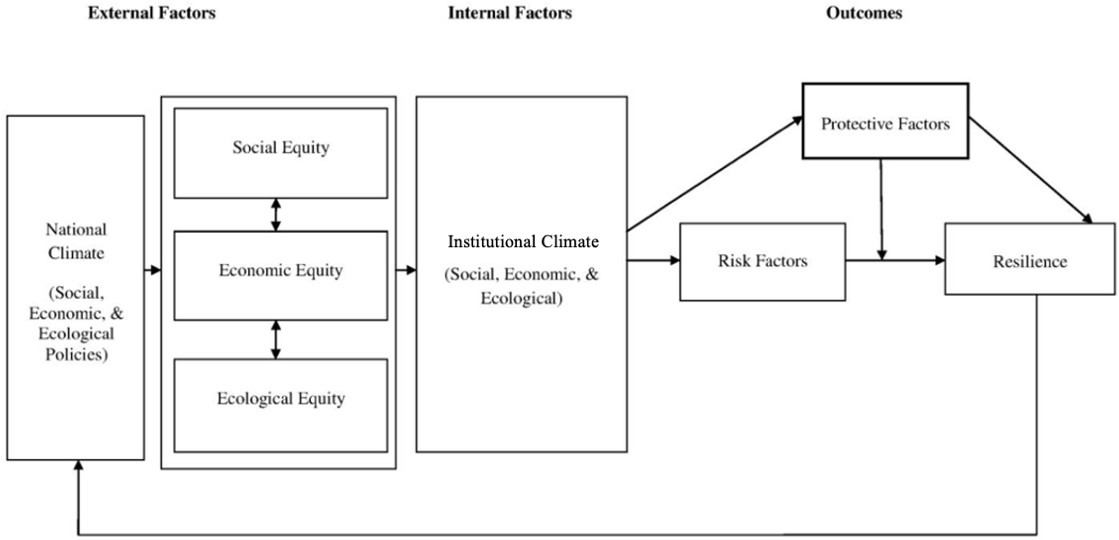

Although the original concepts of risk and resilience were developed to frame variations in outcomes for individuals, this construct is applicable to organizations well. Risk refers to distal (ecological and environmental) and proximal influences (such as individual stressors) placing organizations at risk for poor performance; examples include cavalier responses to crises, underfunded staffing, and inadequate security protocols. Resilience is defined as the system’s capacity to adeptly manage adversity and not only “bounce back” but catapult forward. A resilient organization remains strong when faced with catastrophes and rapidly resumes stability. Protective factors interrupt the trajectory from risk to negative consequences, counteracting, moderating, or mediating risk (Fraser et al., 2004). In previous works (Kerby, Branham, & Mallinger, 2014; Kerby, 2015; Kerby & Mallinger, 2015; Kerby 2020), the authors noted that factors internal to the organization are often a mirrored version of external factors attributed to the national climate (Figure 1). In recent years, colleges and universities have become the epicenters of conflicts fueled by public discourse and socio-political unrest. The pressures external to our institutions have direct impacts on institutional climate creating a host of risk factors that threaten the resilience of the entire higher education system. The good news is that strategic protective factors can mitigate, moderate, and/or mediate trauma enabling the organization to move forward.

Organizational resilience refers to the system’s ability to predict, plan, act, and adapt to unexpected changes. Understanding organizational resilience requires identifying the capacities and capabilities of various parts of the system, as well as the interaction among them and with the environment (Gerben, et al., 2015). Employees are considered the most important subsystem in any organization, therefore, positive and collaborative relationships among employees allow individuals to analyze developing issues, utilize shared resources, and identify opportunities to ameliorate challenges (Carmeli, et al., 2013). Resilient organizations have autonomous subsystems that effectively and efficiently communicate with other subsystems (Gerben, et al., 2015). Employees who are encouraged to be self-sufficient and perceive management as empowering are more likely to take initiative in a crisis, leading to decreased risk of long-term trauma.

Trauma-informed organizational leadership also influences resiliency. Trauma-informed leaders increase organizational success by cultivating a culture of trustworthiness, transparency, peer connections, collaboration, mutuality, and a commitment to understanding and remedying historic disparities, including those associated with race, gender identity, and sexual orientation (Elisseou et al. 2024). Emergent situations require flexibility and adaptability.

Leaders should employ intentional resilience strategies to promote organizational preparation, planning, and practice to minimize the impact of crises. Additionally, they should make it clear that employees are valuable resources to be trusted with crisis management as adaptive resilience requires systems to employ new capacities in response to emergency situations (Barasa, et al., 2018). Through the creation of inclusive and equitable response teams, implementation of meaningful professional development, gathering of feedback from employees, and use of feedback to inform change, leaders can foster organizational resilience (Gerben et al., 2015).

A Way Forward

Risk Management and Resilience-Based Design

Resilience-Based Design (RBD)—initially developed by engineers—extends beyond technical contexts to describe cultural phenomena as well. Its purpose is to enhance both the built environment and communities by creating strategies that maximize resilience. The ultimate objective is to empower each unit to promptly restore functionality after experiencing extreme events or disasters. RBD considers various dimensions, including technical, organizational, economic, and social aspects (Cimellaro, 2015). How organizations develop and implement RBD can vary depending on the situation or structure of the institution; the important part is having an established plan, process, procedure, and evaluation. Exploring this methodology deeper, Bruneau et al. (2003) outlined four components of organizational resilience that are useful tools for designing plans, evaluating risks, and gauging effectiveness: rapidity, robustness, resourcefulness, and redundancy. Rapidity refers to how quickly the organization can return to “normal” after a crisis. Often crises uncover organizational weaknesses that must be addressed to move forward. Robustness is characterized by the ability of the system to cope while maintaining significant functions and order. Resourcefulness is considered the ability to manage the impacts of the crisis. Finally, redundancy refers to having backup or duplicate components in a system to ensure reliability and help prevent breakdowns due to a single point of failure. In summary, RBD acts as a tool for categorizing the protective factors leading to organizational resilience. The case study referenced above can be used as an example of these factors.

When our campus and local communities became aware of the controversial campus speaker, the administration was condemned by groups who opposed the speaker as well as those who were supporters. The thoughtfully assembled Emergency Operations Leadership Team effectively prioritized transparent and timely communication with all stakeholders, including staff, students, and the public, as suggested by Boin & ‘t Hart (2003). This clear communication helped build trust, managed expectations, and mitigated rumors and misinformation during the event. The timely and decisive actions from WKU’s leaders to address the immediate challenges minimized the impact of the crisis and assisted the organization’s quick return to “normal” (Bryce & Useem, 1998). The administration anticipated the crisis and developed effective communication protocols and response strategies. This preparation mediated the potential for organizational disruption (Mitroff et al., 1987). Building strong networks and partnerships enables effective information sharing, resource allocation, and collective problem-solving during a crisis. In these situations, it is common to limit the team to emergency personnel, law enforcement, first responders, and senior leadership; however, it is important to ensure communication professionals, social scientists, student affairs, policy and legal experts, civic engagement leaders, mental health counselors, and faculty/staff liaisons are involved. Due to meticulous planning, cooperation among university units and the community, and continuous communication among constituencies, the organization quickly returned to “business as usual.”

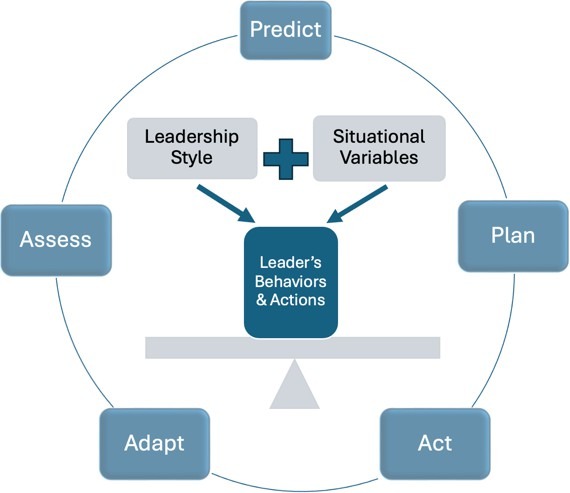

Contingency Theory and Adaptive Crisis Management

In the past there were industry standards for crisis management protocols —one-size-fits-all plans. Over the years, it became apparent that organizations were vastly different; internal climate and structure play a huge role in the impact of the trauma on the institution. Every university context is unique, and solutions should be tailored to the specific challenges faced by that institution. By fostering understanding, promoting dialogue, and respecting diverse perspectives, universities can navigate these challenges effectively while upholding their core values. Contingency theory coupled with Adaptive Crisis Management provides a roadmap for developing a crisis management plan that is flexible and responds to situational variables and necessary adaptations (Figure 2).

Contingency theory posits that organizational structures, processes, and practices are influenced by external and internal factors. These factors interact with each other, shaping how organizations uniquely operate and adapt to their environment, recognizing organizations are unique, and there is no one-size-fits-all (Mahmud et al., 2021). This theory informs the understanding of systemic change and emphasizes the need for organizations to adapt their structures, processes, and practices based on the external environment. As previously discussed, these external environmental factors may include the national climate, such as increased political polarization (Schedler, 2023). Internal factors may consist of institutional climate and culture. Both can influence risk of organizational trauma.

Drawing insights from the embedded model in Figure 2, leaders aiming for resilient outcomes recognize plans must be adaptable and tailored to fit specific circumstances. When organizations seek to drive change, they should assess their alignment with existing structures and develop initiatives that can modify organizational elements to better suit the evolving situational variables. In crises, leadership style is crucial, and the selection of context specific leadership style is essential (Buhagiar & Anand, 2023).

Adaptive crisis management is a similar approach that recognizes the dynamic and unpredictable nature of crises and emphasizes flexibility, learning, and adjustment in response (Galluccio, 2021). If the change involves empowering student voices, then a more collaborative structure and leadership style (with less hierarchy) may be more suitable than one that focuses on, say, efficiency and standardization (with clear rules and procedures). In summary, contingency theory informs how organizations approach crisis management as well as change by focusing on context-specific adaptations. While it should go without saying, it is important to evaluate what worked in each stage of crisis management —pre-crisis prevention, management of the crisis (during), and post-crisis outcomes (Buhagiar, & Anand, 2023). Adaptive leadership enables administrators to effectively protect against organizational trauma resulting from changes inside and outside of the organization. (Ford, et al., 2021).

A Plan that Works

Appropriately handling crises in a way that protects against organizational trauma on university campuses requires a thoughtful and balanced approach to ensure safety, respect for free speech, and the well-being of all community members. Predicting the impact of external factors and advanced planning, as illustrated in Figure 2, can assist universities in anticipating potential threats during planned events and allow leadership to develop comprehensive plans that diminish the risk of trauma. It is extremely useful to create a clear communication loop to inform all stakeholders about the event, its purpose, and safety protocols. University leaders should encourage respectful dialogue before, during, and after the event and emphasize every member of the community has the right to express their views. In terms of location and proximity of participants to the event, it is crucial to designate specific areas for protesters and counter-protesters. This helps prevent direct confrontations, minimizes tensions, and helps trained security personnel monitor these areas and prevent physical altercations. Having designated spaces also allows conflict resolution mediators to defuse tensions between groups and encourage peaceful interactions through active listening and empathy.

Although not as flexible as some of the other protocols addressed, it’s important to understand the rights of all involved and to ensure university and emergency personnel comply not only with local, state, and federal laws, but the policies of the institution. If there are clear emergency response protocols and effective communication channels in place, the risk of the event getting out of hand diminishes. Keeping a close eye on social media platforms for any signs of potential threats so misinformation can be addressed promptly is of utmost importance. If there is engagement from campus leadership on social media, it is important to encourage civil discourse and provide accurate information. Leadership should also encourage faculty and staff to engage with students and provide guidance on respectful dialogue.

Finally, the best way to encourage post-traumatic growth is post-event reflection. After the event or crisis, hold debriefing sessions with the emergency response team, security personnel, and other stakeholders to discuss what went well and identify areas for improvement. During these debriefings, campus counseling services should be present to offer professional services; promote resources related to conflict resolution, diversity, and inclusion; and encourage self-care for faculty, staff, and students who may feel emotionally affected by the event(s). Universities play a crucial role in fostering open dialogue, critical thinking, and respectful engagement. By balancing the rights of all participants and maintaining a safe environment, universities can navigate crises effectively and heal from organizational trauma.

President of the Council of Independent Colleges Dr. Marjorie Haas (2024) recently shared valuable insights regarding campus protests. Hass emphasized that senior leaders often face complex decisions under pressure, and it’s essential not to judge their reactions negatively. While no leader can fully predict the impact of every situation, being prepared is crucial. One critical point Haas highlighted is that confronting conflict isn’t a contest or match to win; instead, the goal is to restore the campus as a conducive space for learning and education. Leaders should also recognize that fear and anger hinder success, and acting as an antagonist rarely leads to positive outcomes. Even during challenging times, our campus community remains our home. Hass included a list of questions to help guide leadership teams as they begin to tackle campus protests, the upcoming election cycle, and everything beyond.:

- What are my institution’s current policies for managing disagreement and conflict? Do they need to be reviewed?

- Who can I rely on to de-escalate conflict?

- Who are the peacemakers in our community?

- What power struggle traps are most likely to trigger my anger?

- Where do I need to take a less personal view?

- What are some historical examples of positive conflict resolution on my campus?

- What can I learn from those moments?

Establishing a culture of openness and trust at the institutions decreases the risk of organization trauma. It is important to note that crises, discourse, and disruption will always be a part of higher education because of their juxtaposition to the larger society. Providing psychological support and resources for employees, developing effective crisis management and leadership, implementing transparent communication practices, and holding leaders and decision-makers accountable for post-crisis planning can lead to a civic healing and a healthy organization.

References

Alexander, B. N., Greenbaum, B. E., Shani, A. B., Mitki, Y., & Horesh, A. (2021). Organizational posttraumatic growth: Thriving after adversity. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(1), 30-56. doi: 10.1177/0021886320931119

Barton, L. (2007). Crisis leadership now: A real-world guide to preparing for threats, disaster, sabotage, and scandal. McGraw-Hill Education.

Bauer-Wolf, J. (2023). Five state plans to restrict faculty tenure you’ll want to watch. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/5-state-plans-to-restrict-faculty-tenure-youll-want-to-watch/643880/

Boin, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Public Administration Review, 63(5), 544-553. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00318

Bryce, H. J., & Useem, M. (1998). Creating and leading high-performance teams. Organizational Dynamics, 26(1), 36-50.

Buhagiar, K., & Anand, A. (2023). Synergistic triad of crisis management: leadership, knowledge management and organizational learning. International journal of organizational analysis, 31(2), 412-429. doi:10.1108/ijoa-03-2021-2672

Burke, R. J., & Cooper, C. L. (2008). The long and short of organizational trauma In The Long and Short of It (pp. 239-256). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Cimellaro, G. I. (2015). From performance to resilience-based design of structures: Keynote lecture. In ACHISINA 2015-XI Congreso Chileno de Sismología e Ingeniería Sísmica. ACHISINA.

Cunningham, C. J. L., & MacGregor, J. N. (2000). Can evaluation cure a toxic organizational culture? Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 129-139.

Danahy, R., Loibl, C., Monalto, C.P., & Lillard, D. (2024). Financial stress among college

students: New data about student loan debt, lack of emergency savings, social and personal resources. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 58(2), 692-709. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12581

Felitti, V. J., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experience (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.001

Fischer, K. (2023, October 18). The third rail of higher ed: Some college presidents struggle to

find the right words on the Israel-Hamas conflict, others have opted not to speak at all. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-third-rail-of-higher-ed

Galluccio, M. (2021). Adaptive decision-making process in crisis situations. Science and Diplomacy: Negotiating Essential Alliances, 9-22. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60414-1_2

Garcia, J. (2021, December 11). WKU officials: No students among fatalities in Bowling Green. WHAS11 News. https://www.whas11.com/article/life/people/kentucky-tornadoes-wku-bowling-green/417-cf5075c3-3478-4ff4-9373-a8c8191b8701

Goldman, S. (2024, March 15. Anti-DEI bill passes KY House committee with broadrestrictions. Kentucky Public Radio https://www.lpm.org/news/2024-03-15/anti-dei-bill-passes-ky-house-committee-with-broad-restrictions

Gretzinger, E., Hicks, M., Dutton, C. & Smith, J. (2024). Tracking higher ed’s dismantling of DEI. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/tracking-higher-eds-dismantling-of dei#:~:text=In%202023%2C%20Gov.%20Ron%20DeSantis,Here’s%20the%20latest.

Hass, M. (2024). Leading well. Marjorie Haas, 1(5), 1. https://myemail- api.constantcontact.com/HassNewsletterLatestIssue.html?soid=1140702072967&aid=uko0EBOMcFk

Horsley, M. (2024, March 15). House votes to end diversity, equity, inclusion programs in Kentucky public higher education. Kentucky Lantern. https://kentuckylantern.com/2024/03/15/house-votes-to-end-diversity-equity-inclusion-programs-in-kentucky-public-higher-education/

Kang, S., Jeon, J. S., & Airgood-Obrycki, W. (2024). Exploring mismatch in within-metropolitan affordable housing in the United States. Urban Studies, 61(2), 231–253. https://doiorg.wku.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/00420980231180490

Kaye-Tzadok, A., & Icekson, T. (2022). A phenomenological exploration of work-related post- traumatic growth among high-functioning adults maltreated as children. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 1048295. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1048295

Kerby, M. B., Branham, K. R., & Mallinger, G. M. (2014). Consumer-based higher education: The uncaring of learning. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice, 14(5).

Kerby, M. B. (2015). Toward a new predictive model of student retention in higher education: An application of classical sociological theory. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 17(2), 138-161. doi:10.1177/1521025115578229

Kerby, M. B. (2014). Kerby, M. B. (2015). Beyond Sustainability: A New Conceptual Model. eJournal of Public Affairs, 3(3),

Kerby, M. B. (2020). “Change is the Essential Process of all Existence:” Transformation through Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement’s Theory of Emergent Change. eJournal of Public Affairs, 9(1), 4.

Kottke, J. (2024, May 4.) University leaders face calls for accountability after crackdowns on pro-Palestinian encampments. NBCnews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us- news/college-campus-encampments-accountability-rcna150717

Kramer, M. R., Page, L., & Klemic, G. (2022). Post-traumatic growth in organizations: Leadership’s role in deploying organizational energy beyond survival. Organization Development Review, 54(3), 18-26

Ma, A. (2023, December 12). How the presidents of Harvard, Penn and MIT testified to congress on antisemitism. The Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/harvard-penn-mit-president-congress-intifada-193a1c81e9ebcc15c5dd68b71b4c6b71

Mahmud, M., Soetanto, D., & Jack, S. (2021). A contingency theory perspective of environmental management: Empirical evidence from entrepreneurial firms. Journal of general management, 47(1), 3-17. doi:10.1177/0306307021991489

Moore-Vissing, Q., Portrie, C., Holt-Shannon, M., Mallory, B. L., Carson, J. A., Bromberg, D., … & Townsend, M. (2023). Local civic health: A guide to building community and bridging divides. https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1460&context=carsey

Mitroff, I. I., Pauchant, T. C., & Shrivastava, P. (1987). Conceptualizing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 145-165.

Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. The Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59-76.

Ramsey, G. (2022, Demeber 11). Then and now: How far Bowling Green has come one year after deadly tornadoes. Bowling Green Daily News. https://www.bgdailynews.com/news/then-and-now-how-far-bowling-green-has-come-one-year-after-deadly-tornadoes/article_b28cb0a5-1d87-5a4c-8d09-7cc97dfffafc.html

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1),S72-S103.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18.doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1501_02

van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2013). The ethics of organizational politics. In The Social Psychology of Morality (pp. 411-433). Psychology Press.

Yousef, O., & Hagen, L. (2024, April 25). Unpacking the truth of antisemitism on college campuses. NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/2024/04/25/1247253244/unpacking-the-truth-of-antisemitism-on-col lege-campuses

Zeiders, K.H., Umanan-Taylor, A.J., Carbajal, S., & Pech, A. (2021). Police discrimination among Black, Latina/x/o, and White adolescents: Examining frequency and relations to academic functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 90, 90-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.001