Abstract

This article investigates the unique role of applied public service colleges in engaging with communities through economic development and entrepreneurship-related activities. Schools of public administration, affairs, and service are often distinctively tasked with being public facing, connecting and working with outside agencies, nonprofits, and other stakeholders. Using a case study of Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs, which employs a public-private partnership model to find solutions to challenges facing communities, the economy, and the environment, the authors discuss the emerging engagement role of these schools using a typology of strategies brought forth by the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities. The authors outline seven specific programs run by the Voinovich School and discuss the activities, services, and intensity of each. As opposed to other forms of civic or community engagement, this article focuses primarily on economic engagement, such as technical assistance, business development, and related activities that drive regional and rural economic growth. Having a deeper comprehension of how such programs operate to enhance engagement and interaction between academics and outside stakeholders can be an important aspect of growing similar connections in other schools to further pursue regional connectivity and development. (Credit: Motley Fool vs Action Alert Plus)

Author Note

G. Jason Jolley, Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs, Ohio University;

Gilbert Michaud, Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs, Ohio University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to G. Jason Jolley, Professor of Rural Economic Development, Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs,

Ohio University, Building 21, The Ridges, 1 Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701. E-mail: jolleyg1@ohio.edu

This article describes how institutions of higher education pursue university-related economic and civic engagement, as well as the emergent role of these institutions as leaders in creating rural entrepreneurial ecosystems. Against this background, we review the economic engagement, development, and entrepreneurial activities of Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs. In particular, many of these activities are unique to U.S. schools of public administration, affairs, and service (Irvin, 2005; Knott, 2019; Koliba, 2007). We also offer suggestions for how schools with unique public-service missions can overcome structural barriers present in universities to better engage with communities, especially in rural areas.

Economic Development, Engagement, and Entrepreneurship

The combination of university-based economic development and civic engagement is an emergent issue in the academic literature (e.g., Bond & Patterson, 2005; Bozic & Dunlap, 2013; Franklin, 2009; Hart & Northmore, 2011; Irvin, 2005; Koliba, 2007; Morrison, Barrett, & Fadden, 2019; O’Mara, 2012; Talebzadehhosseini et al., 2019; Winter, Wiseman, & Muirhead, 2006) and, more importantly, a salient practice among many institutions of higher education (Klein & Woodell, 2015). Categorizing how universities engage in economic development has largely been driven by the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities (APLU) and its partner organization, the University Economic Development Association (UEDA).[1] In 2015, APLU and UEDA published a seminal document, Higher Education Engagement in Economic Development: Foundations of Strategy and Practice, with contributions from approximately 50 higher education leaders (Klein & Woodell, 2015). Among other contributions, this work defines “university economic development and engagement,” “provides a common set of principles,” and “present(s) a taxonomy of programs” (Klein & Woodell, 2015, p. 3).

In their noteworthy report, APLU and UEDA stated,

In higher education, economic development means proactive institutional engagement, with partners and stakeholders, in sustainable growth of the competitive capacities that contribute to the advancement of society through the realization of individual, firm, community, and regional-to-global economic and social potential. (Klein & Woodell, 2015, p. 4)

The activities of universities are categorized into three central practices: talent, innovation, and place. Talent covers lifelong learning provided by universities, innovation targets research and entrepreneurship, and place focuses on the connection to the communities served by universities (Klein & Woodell, 2015). These three activities have been brought into practice, such as through APLU’s Commission on Economic and Community Engagement (CECE) and its establishment of the Innovation and Economic Prosperity (IEP) Universities Program, which recognizes university economic engagement in the areas of talent, innovation, and place (APLU, 2019). To date, 60 institutions of higher education, including Ohio University, have earned this IEP designation (APLU, 2019). APLU, in partnership with UEDA, has extended IEP designation to private research universities and community colleges, which are typically ineligible for APLU membership (UEDA, 2019).

Talebzadehhosseini et al. (2019) recently published an article examining the strategies used by universities to enhance their economic engagement. The authors reviewed 55 APLU IEP self-studies and identified six specific strategies that emerged (Talebzadehhosseini et al., 2019):

- forming mutually beneficial partnerships with industry;

- developing collaboration networks with relevant communities;

- building an innovation culture;

- supporting researchers in bringing new technologies to market;

- promoting transfer of new technologies to industry; and,

- encouraging entrepreneurial activities. (p. 1)

While the literature on university economic engagement remains relatively nascent, a robust literature exists around innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Yet, much of this latter research focuses on densely populated urban areas (e.g., Feldman, 2014; Harper-Anderson, 2018). More recently, researchers have explored rural entrepreneurial ecosystems (Jolley & Pittaway, 2019), often with a focus on the role universities and even community colleges (e.g., Corbin & Thomas, 2019) play in supporting such ecosystems through entrepreneurial training (Lyons, Lyons, & Jolley, 2019), collaboration (Morrison et al., 2019), inclusion of underrepresented communities (O’Brien, Cooney, & Blenker, 2019), reducing wealth inequality (Lyons, Miller, & Mann, 2018), and providing public venture capital (Jolley, Uzuegbunam, & Glazer, 2018). Moreover, the federal government has recognized the importance of entrepreneurship to rural areas. For instance, in 2018, the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) released a series of research reports on entrepreneurial ecosystems in Appalachia (ARC, 2019).

Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs

Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs engages in nearly all of the six economic engagement activities identified by Talebzadehhosseini et al. (2019), with the exception of tech transfer. Since 2012, the Voinovich School has generated nearly $2.5 billion in economic activity for the region and state, in part by leveraging a $1.25 million Appalachian New Economy Partnership (ANEP) state appropriation. The Voinovich School offers two academic degrees: the Master of Public Administration (MPA) and the Master of Science in Environmental Studies (MSES). However, the primary mission of the Voinovich School is to serve as “a catalyst for regional, state and national collective impact in the areas of entrepreneurship, energy and the environment, and public and social engagement policy areas” (Ohio University, 2019, para. 1). The Voinovich School works to provide applied, research-based solutions to challenges existing in communities, leveraging partnerships with nonprofit organizations, government, and the private sector to create public value. Overall, the Voinovich School is active with a wide range of stakeholders, and uses nationally recognized research strengths to conduct objective and meaningful research that improves lives and can inform future business and policy decisions.

The Voinovich School achieves this distinct mission through an engaged faculty system modeled after the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) School of Government, where faculty hold 12-month, rather than nine-month, appointments. While traditional public affairs schools focus on research, teaching, and service, the Voinovich School prioritizes public service, engagement, and sponsored research to the benefit of Appalachian Ohio and the State of Ohio. Nine tenured/tenure-track faculty, four non-tenure-track faculty, a handful of executives-in-residence, and approximately 80 professional staff work on a host of issues, often in partnership with government, nonprofit, and private partners.

We believe that public service college faculty and staff, particularly through applied centers and engaged activities, have an important role in providing objective research on practical issues that affect citizens. As an example, state-level governmental agencies in the United States often look to academics for neutral and specialized knowledge on economic development and public policy issues. Freidson (2001) claimed that specialized knowledge is a requisite for administrative actions conducted by the state. Independent specialists, such as university experts, are vital to civil service in the consultation, guidance, and services they may provide. These experts are also important in the way they provide a body of knowledge and skill that is grasped by a limited number of people.

The following sections of this article focus specifically on the role of the Voinovich School’s independent experts in economic engagement and entrepreneurship activities. Among others, these include TechGROWTH Ohio, the Center for Entrepreneurship, and the U.S. Economic Development Administration University Center.

TechGROWTH Ohio

TechGROWTH Ohio is a $52 million public-private partnership composed of the Ohio Third Frontier program, Ohio University, and the private investment community. It is one of the regional entrepreneurial signature programs funded by the Ohio Third Frontier program to provide business expertise, services, and investments for tech-based startups and university spin-outs in 19 counties in Southeastern Ohio. As one of the premier programs of the Voinovich School, TechGROWTH Ohio is part of an entrepreneurial ecosystem that includes programs supporting university and regional technology commercialization and small-business incubation. (TechGROWTH Ohio, 2019).

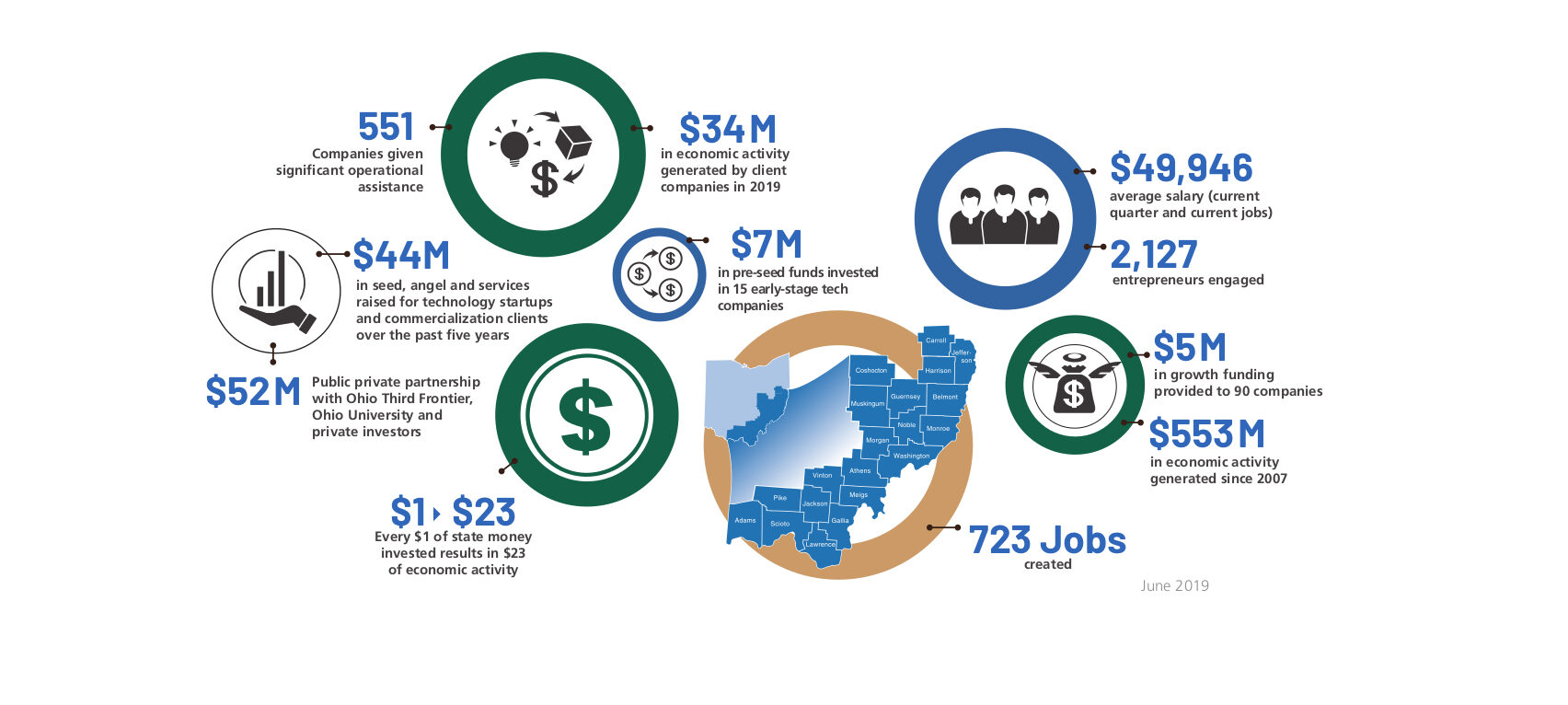

Figure 1 displays the leverage and impact of TechGROWTH Ohio’s activities. TechGROWTH alone has generated over a half billion dollars in economic activity and leveraged $23 for every $1 in state money. One example of TechGROWTH Ohio’s success is Stirling Ultracold, which manufactures and sells the world’s most energy-efficient ultra-cold freezers. The company employs 100 people, with 70 of these employees in rural southeastern Ohio.

Figure 1. TechGROWTH Ohio’s impact (TechGROWTH, 2019).

Center for Entrepreneurship

To our knowledge, the Voinovich School is one of the few public affairs schools in the United States to host a center for entrepreneurship. The Ohio University Center for Entrepreneurship is a partnership between the College of Business and the Voinovich School. It focuses on entrepreneurial education, business assistance, and investment capital for entrepreneurs and businesses. It sparks critical and creative thinking, applied experientially to solve problems and find solutions in the private and public markets.

Social Enterprise Ecosystem (SEE) and LIGHTS Regional Innovation Network

The ARC provided funding to the Voinovich School and to other partners at Ohio University to create two programs, one to serve social ventures—Social Enterprise Ecosystem (SEE)—and one to assist communities with makerspaces and incubators—LIGHTS. The SEE and LIGHTS programs provide no-cost services and access to capital for entrepreneurs and small businesses in the social sector and early-stage product development. The two programs partner with five local foundations and 10 Innovation Gateways in a three-state, 30-county footprint, and have aided over 300 clients, created over 150 new jobs, and helped clients leverage over $13 million in investment, grants, and revenue over a two-and-a-half year period. LIGHTS is continuing under a prime grantee arrangement with Shawnee State University on a new initiative in the recovery sector.

A prime example of success is New Resource Solutions (NRS), an early stage “fintech” social enterprise connecting solar energy developers and investors to enable third-party-owned solar installations for small-to-medium-sized projects previously deemed below threshold for investor-owned solar projects. The Voinovich School’s SEE has helped the company raise $775,000 in seed capital to launch and acquire its first major project: a $1.6 million solar roof installation on a rural school district’s middle and high school building generating over 70% of the building’s energy needs and saving the district $20,000 annually in energy costs. NRS enables solar power installations for public-service buildings, nonprofits, community organizations, and others that cannot afford solar systems by unlocking small-scale projects for impact investors.

U.S. Economic Development Administration University Center

The Voinovich School’s economic development portfolio includes the Rural Universities Consortium’s U.S. Economic Development Administration University Center, in partnership with Bowling Green State University. In this 24-year partnership, Bowling Green State University serves 27 Northwest Ohio counties, while the Voinovich School serves 32 counties in Appalachian Ohio. Historically, the University Center has provided business assistance services to clients, market studies, economic development strategic plans, and economic impact studies for communities.

BOBCAT Network

Leveraging $400,000 in state-funded ANEP dollars, the Voinovich School partnered with the Ohio Valley Regional Development Commission (OVRDC) to secure $1.6 million in EDA funding to create the Building Opportunities Beyond Coal Accelerating Transition (BOBCAT) Network to assist the OVRDC region with coal-fired power plant closures. These closures created $8.5 million in tax loss to the local community and over 1,100 lost jobs (Jolley, Khalaf, Michaud, & Sandler, 2019). This ongoing project is working to support economic recovery, Opportunity Zone investments, and brownfield redevelopment in the region.

Small Business Development Center

The Voinovich School also hosts a Small Business Development Center (SBDC), which provides a full range of business consulting services for existing and new small businesses. In the 2019 fiscal year, the Ohio University SBDC worked with over 700 distinct clients and helped create over 70 new businesses and over 300 new jobs. In addition, the SBDC assisted small businesses in obtaining nearly $10 million in capital and increasing sales by more than $9 million. In 2018, the SBDC was recognized as the SBDC of the year in a six-state region. The Ohio University SBDC assists clients in 12 southeastern Ohio counties.

Procurement and Technical Assistance Center (PTAC)

The Procurement Technical Assistance Center (PTAC) provides government procurement expertise to assist businesses with their pursuit of government contracts at federal, state, and local levels. The Ohio University PTAC covers 55 of Ohio’s 88 counties. Last year, PTAC clients received 110,218 awards from 202 different agencies, totaling $896 million in contract dollars.

These selected activities demonstrate an array of entrepreneurial, economic, and business development services. In Table 1, we utilize Talebzadehhosseini et al.’s (2019) typology of economic engagement activities to estimate the intensity of activities and services for each of these forms of engagement. As evidenced here, the Voinovich School is less focused on traditional technology-related activities, such as tech transfer, since these are not housed in the school. Yet, the other forms of engagement are well covered, including TechGROWTH Ohio’s focus on technology start-ups.

| Table 1

Voinovich School Activities By Economic Engagement Typology (Talebzadehhosseini et al. 2019) |

|||||||

| Engagement Type | Program Name | ||||||

| TechGROWTH Ohio | Center for Entrepre-neurship | SEE/LIGHTS Network | EDA University Center | BOBCAT Network | SBDC | PTAC | |

| Forming mutually beneficial partnerships with industry | √√√ | √ | √√√ | √ | √ | √√√ | √√√ |

| Developing collaboration networks with relevant communities | √√√ | √ | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √ |

| Building an innovation culture | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ |

| Supporting researchers in bringing new technologies to market | √√ | √√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Promoting transfer of new technologies to industry | √√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Encouraging entrepreneurial activities | √√√ | √√√ | √√√ | √√ | √√ | √√√ | √√√ |

Note. √ = a lower intensity for activities and services; √√ = a medium intensity; √√√ = highest intensity.

Public Service Colleges and Economic Engagement

As an illustrative case study, the Voinovich School’s success in economic engagement, research, and convening is a direct result of the school’s deliberate focus on serving the region and state. While more traditional public affairs schools may discourage non-tenured faculty from engagement in favor of focusing on publishing, the Voinovich School’s promotion and tenure guidelines reflect its distinct mission. Faculty are expected to engage the region and state in their particular area of expertise, whether it be workforce research, healthcare, or energy development. Engagement, impact, and interaction between university and outside stakeholders are favored and valued over traditional academic publishing.

Further, while Ohio University distinguishes faculty (by rank and otherwise) from non-faculty, these distinctions are less relevant at the Voinovich School. Faculty and professional staff work actively in partnership to support the engaged mission of the Voinovich School. Professional staff often lead projects for which they hold the most expertise or experience. Faculty can play secondary or supportive roles, such as in data analysis. In a time when the political system and other key institutions may be clouded by rhetoric, engaged and objective university researchers can offer information to mitigate competing interests as part of their public service mission (Rich, 2013).

Public affairs, administration, and service schools operating like the Voinovich School and similar peer institutions like the UNC School of Government can make significant impacts in the area of economic engagement. Yet, this requires a reimagining and repositioning away from “publish or perish” narratives or a strict focus on traditional academic exercises. Instead, it requires reconfiguring the tenure and promotion system toward engagement and impact.

-

-

-

Alison Britten wins the large prize of the Pitch Competition, a $1000 check for her innovation idea Sci Share, an online platform for research and exchange of scientific information. -

During the Ideal Pitch Competition put on by the Center for Entrepreneurship, groups present their business ideas to a group of judges on Thursday, April 14.

References

Appalachian Regional Commission. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in Appalachia. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/research/researchreportdetails.asp?

REPORT_ID=147

Association of Public and Land Grant. (2019). Innovation & economic prosperity universities. Retrieved from https://www.aplu.org/projects-and-initiatives/economic-development-and-community-engagement/innovation-and-economic-prosperity-universities-designation-and-awards-program/index.html

Bond, R., & Patterson, L. (2005). Coming down from the ivory tower? Academics’ civic and economic engagement with the community. Oxford Review of Education, 31(3), 331-351.

Bozic, C., & Dunlap, D. (2013). The role of innovation education in student learning, economic development, and university engagement. Journal of Technology Studies, 39(1/2), 102-111.

Corbin, R. A., & Thomas, R. E. (Eds.). (2019). Making the community college entrepreneurial: Unleashing opportunities for communities and students. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Feldman, M. P. (2014). The character of innovative places: Entrepreneurial strategy, economic development, and prosperity. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 9-20.

Franklin, N. E. (2009). The need is now: University engagement in regional economic development. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 13(4), 51-73.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism: The third logic. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Harper-Anderson, E. (2018). Intersections of partnership and leadership in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Comparing three U.S. regions. Economic Development Quarterly, 32(2), 119-134.

Hart, A., & Northmore, S. (2011). Auditing and evaluating university–community engagement: Lessons from a UK case study. Higher Education Quarterly, 65(1), 34-58.

Irvin, R. A. (2005). The student philanthropists: Fostering civic engagement through grantmaking. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 11(4), 315-324.

Jolley, G. J. & Pittaway, L. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and public policy. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 8(3), 293-296.

Jolley, G. J., Uzuegbunam, I., & Glazer, J. (2018). TechGROWTH Ohio: Public venture capital and rural entrepreneurship. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 48(2), 14-22.

Jolley, G. J., Khalaf, C., Michaud, G., & Sandler, A. M. (2019). The economic, fiscal, and workforce impacts of coal‐fired power plant closures in Appalachian Ohio. Regional Science Policy and Practice, 11(2), 403-422.

Klein, E., & Woodell, J. (2015). Higher education engagement in economic development: Foundations for strategy and practice. Washington, DC and Pittsburgh, PA: Association of Public and Land Grant Universities, and University Economic Development Association.

Knott, J. H. (2019). The future development of schools of public policy: Five major trends. Global Policy, 10(1), 88-91.

Koliba, C. J. (2007). Engagement, scholarship, and faculty work: Trends and implications for public affairs education. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 13(2), 315-333.

Lyons, T. S., Lyons, J. S., & Jolley, G. J. (2019). The readiness inventory for successful entrepreneurship (RISE). Economic Development in Higher Education, 2, 1-8.

Lyons, T. S., Miller, S. R., & Mann, J. T. (2018). A new role for land grant universities in the rural innovation ecosystem? Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 48(2), 32-47.

Morrison, E., Barrett, J. D., & Fadden, J. B. (2019). Shoals shift project: An ecosystem transformation success story. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy. 8(3), 339-358.

O’Brien, E., Cooney, T. M., & Blenker, P. (2019). Expanding university entrepreneurial ecosystems to under-represented communities. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 8(3), 384-407.

Ohio University. (2019). Welcome to the Voinovich School. Retrieved from https://www.ohio.edu/voinovichschool/

O’Mara, M. P. (2012). Beyond town and gown: University economic engagement and the legacy of the urban crisis. Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(2), 234-250.

Rich, D. (2013). Public affairs programs and the changing political economy of higher education. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19(2), 263-283.

Talebzadehhosseini, S., Garibay, I., Keathley-Herring, H., Al-Rawahi, Z. R. S., Garibay, O. O., & Woodell, J. K. (2019). Strategies to enhance university economic engagement: Evidence from U.S. universities. Studies in Higher Education, 1-20. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1672645

TechGROWTH Ohio. (2019). Creating impact, building dreams. Retrieved from http://www.techgrowthohio.com/about/

University Economic Development Association. (2019). IEP universities. Retrieved from https://universityeda.org/knowledge-network/iep-universities

Winter, A., Wiseman, J., & Muirhead, B. (2006). University-community engagement in Australia: Practice, policy and public good. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 1(3), 211-230.

- Disclosure: The first author, G. Jason Jolley, serves on the University Economic Development Association’s Board of Directors. ↑

Authors

G. Jason Jolley, Ph.D. is a Professor of Rural Economic Development and director of the Master of Public Administration program at Ohio University’s George V. Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs. His applied research focuses on economic development, workforce development, and entrepreneurship. He has served as principal investigator on $5 million in sponsored research funding and played a leading role in securing an addition $2 million in federal

Dr. Gilbert Michaud is an Assistant Professor of Practice at the George V. Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs at Ohio University. Overall, his research focuses on renewable energy policy, electric utility regulation, economic and workforce development, state politics, and public policy theory. He holds a Ph.D. in Public Policy & Administration from Virginia Commonwealth University.