Abstract

In the study discussed in this article, a group of six faculty members from Weber State University’s Telitha E. Lindquist College of Arts and Humanities tested and applied the Self-Assessment Rubric for the Institutionalization of Community Engagement at the Level of the College Within a University as part of a pilot program. Based on this application of the rubric, the group found that the college tended toward the “Emerging” stage (i.e., Stage 1) for most items, indicating a need to continue developing programs and practices that center on community engagement (CE) within the college. The primary finding from this activity was that CE is fragmented in the college, within its constituent departments, and at the university level. This fragmentation limits the effectiveness of community-engaged learning, teaching, and scholarship. The authors discuss the group’s findings and interpretations of the rubric elements and offer recommendations for future use of the engaged college rubric.

Author Note

Becky Jo Gesteland, Department of English, and Center for Community Engaged Learning, Weber State University; Christy Call, Department of English, Weber State University; Alexander L. Lancaster, Department of Communication, Weber State University; Kathleen “K” Stevenson, Department of Visual Art and Design, Weber State University; Amanda Sowerby, Department of Dance, and Lindquist College of Arts and Humanities, Weber State University; Isabel Asensio, Department of Foreign Languages, Weber State University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Becky Jo Gesteland, Professor of English and Executive Director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning Weber State University, 3910 West Campus Drive, Department 2113, Ogden, UT 84408-2113. E-mail: bgesteland@weber.edu

Community engagement (CE) among higher education institutions remains a topic of particular interest for scholars, with a variety of focuses and outcomes presented in the current literature (e.g., Saltmarsh et al., 2009; Sandmann, Thornton, & Jaeger, 2009). Despite this interest, there is a veritable dearth of scholarly examination of CE at the college level, as the vast majority of the literature centers on the institutional (i.e., university) unit (Saltmarsh, Middleton, & Quan, 2019, in this issue).

One may speculate as to the various causes of this lack of focus on college-level CE. Eckel, Green, Hill, and Mallon (1999) offered a possible explanation by noting that small entities within a university (e.g., a single college) may not have enough influence to affect overall institutional change. According to this view, a college-level focus may be too granular in the larger institutional landscape. Yet, Jaeger, Jameson, and Clayton (2012) made the important argument that lasting change within an institution “will be sustainable only if it is pervasive throughout the institution’s colleges and departments” (p. 152), suggesting the necessity of granular levels of focus. With this view as a basis, we maintain that an analysis of college-level participation in CE offers an essential piece in the overall portrait of institutional practices.

Colleges and departments within institutions of higher education should align with university-level initiatives because the degree of college-level adherence to these initiatives provides a vital index for the coherence and permeation of the university vision. The Telitha E. Lindquist College of Arts and Humanities at Weber State University (WSU) employed Saltmarsh and Middleton’s Self-Assessment Rubric for the Institutionalization of Community Engagement at the Level of the College Within a University (see Saltmarsh, Middleton, & Quan, 2019) to better understand the extent of community-engaged practices during the 2016-2017 academic year. The goal was to elaborate upon the ways that the college unit can help establish and support institutional-level policies and efforts for enhanced community-engaged learning and scholarship.

Literature Review

Before discussing how a college can serve as a focal point for community engagement, it is important to establish some context. Community-engaged scholarship (CES) appears to be an accepted label, with sufficient scope for identifying the diverse ways universities and constitutive colleges approach work that is focused on engaging the learning of a campus within surrounding communities. CES emerged from service-learning, which Bringle and Clayton (2012) defined as

a course or competency-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students (a) participate in mutually identified service activities that benefit the community, and (b) reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of course content, a broader appreciation of the discipline, and an enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility. (pp. 114-115)

Yet, the term service-learning does not fully encompass the goals of CES, which Saltmarsh, Middleton, and Quan (2019) defined as “creative intellectual work based on a high level of professional expertise, the significance of which peers can validate, and which enhances the fulfillment of the mission of the campus/college/department” (p. 3). CES, then, offers a more complete understanding of what may be considered acceptable in community-engaged work among university faculty and students.

CES involves an array of collaborative projects that combine elements of teaching, service, and research, and that focus centrally “on the collaborative development and application of scholarly knowledge to address pressing social issues” (da Cruz, 2018, p. 149). On a micro level (e.g., in a single class or a single publication), CES may focus on a particular community-related issue (see Warren & Mapp, 2011). Arguably, however, CES may also be integrated into larger academic units, including a college or the entire university.

Background

Like many institutions, WSU has largely been driven by initiatives at the university level. In fact, WSU has a rich history of community engagement, especially since the June 2007 creation of the Center for Community Engaged Learning (CCEL), formerly known as the Community Involvement Center. Relying on a strategic partnership between Academic Affairs and Student Affairs, CCEL provides both curricular and co-curricular CE opportunities for campus constituents through various long-standing partnerships with vital local community organizations. The main mission of CCEL is to engage students, faculty, and staff members in service, democratic engagement, and community research that promotes civic participation, builds community capacity, and enhances the educational process. In the 2017-2018 academic year, 4,611 WSU students collectively contributed over 106,043 curricular and co-curricular hours of service.

Three pillars comprise CCEL at WSU: direct service, civic engagement, and community research. Based on the level and quality of involvement in these three domains, WSU has been listed each year since the inception of the award on The President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll. Additionally, since 2012, WSU has served as a lead institution in NASPA’s Lead Initiative for Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement. Further, WSU was awarded the Carnegie Foundation’s Community Engagement Classification for the first time in 2008, with the university maintaining this ranking ever since. The Carnegie Classification acknowledges and classifies universities according to their CE efforts and is “the leading framework for recognizing and describing institutional diversity in U.S. higher education” (Carnegie Classification, n.d.).

WSU has continuously focused on improving CE in general. That said, a culture of CE does not permeate the Lindquist College—let alone other colleges at the university. Some programs, and certainly individual professors, are more engaged than others, and those that are engaged are not necessarily representative of their departments or the college. Thus, while WSU meets the qualifications of an engaged institution per the Carnegie Classification, we cannot claim that our college reflects the university’s same level of engagement.

The former director of CCEL, Dr. Brenda Kowalewski, was appointed to a new position of associate provost of high-impact programs and faculty development in 2016. In this capacity, Kowalewski convened an engagement subcommittee whose purpose centered on establishing high-impact educational experiences (HIEEs) both inside and outside the classroom. HIEEs provide students with foundational and transferable skills to become productive, engaged, and responsible global citizens. Many high-impact practices are characterized by deep levels of student engagement in learning and not just community engagement; thus, CE becomes a distinct practice that seeks to involve community partnerships but that is also synonymous with an array of other high-impact learning practices and approaches. During the 2019-2020 academic year, the work of the subcommittee will move across campus, with a group of faculty and staff willing to pilot the HIEE taxonomy. The goals for this academic year are to identify where HIEEs already exist and where they could expand, and then to provide feedback to the engagement subcommittee.

Given the geographical location of WSU, the area most impacted by university engagement initiatives is the campus home city of Ogden, Utah. Ogden, a large metropolitan region located approximately 40 miles north of Salt Lake City, provides a diverse social and cultural environment for student service-learning projects and for university-community partnerships and developments. With a population of just under 100,000, Ogden is Utah’s seventh largest city. In 2018, the median household income for Ogden City was $46,845; yet, the greater Ogden-Clearfield metropolitan area median income was $72, 112 for the same year (Demographics, 2019). The Diversity Index of Ogden City is 70.3%, registering the city region as both working-class in economic standing and highly diverse ethnically and racially. These same indexes shift to reflect more affluence and less diversity in other outlying areas.

As a testament to its commitment to the communities of Ogden, WSU recently opened the Community Education Center in inner-city Ogden, with the express purpose of benefitting underserved populations by providing services such as an early childhood school headed by the Department of Child and Family Studies and the Ogden Civic Action Network (Ogden CAN). Formed in 2016, Ogden CAN is a coalition of anchor institutions dedicated to improving education, housing, and health in the east central neighborhood of Ogden.

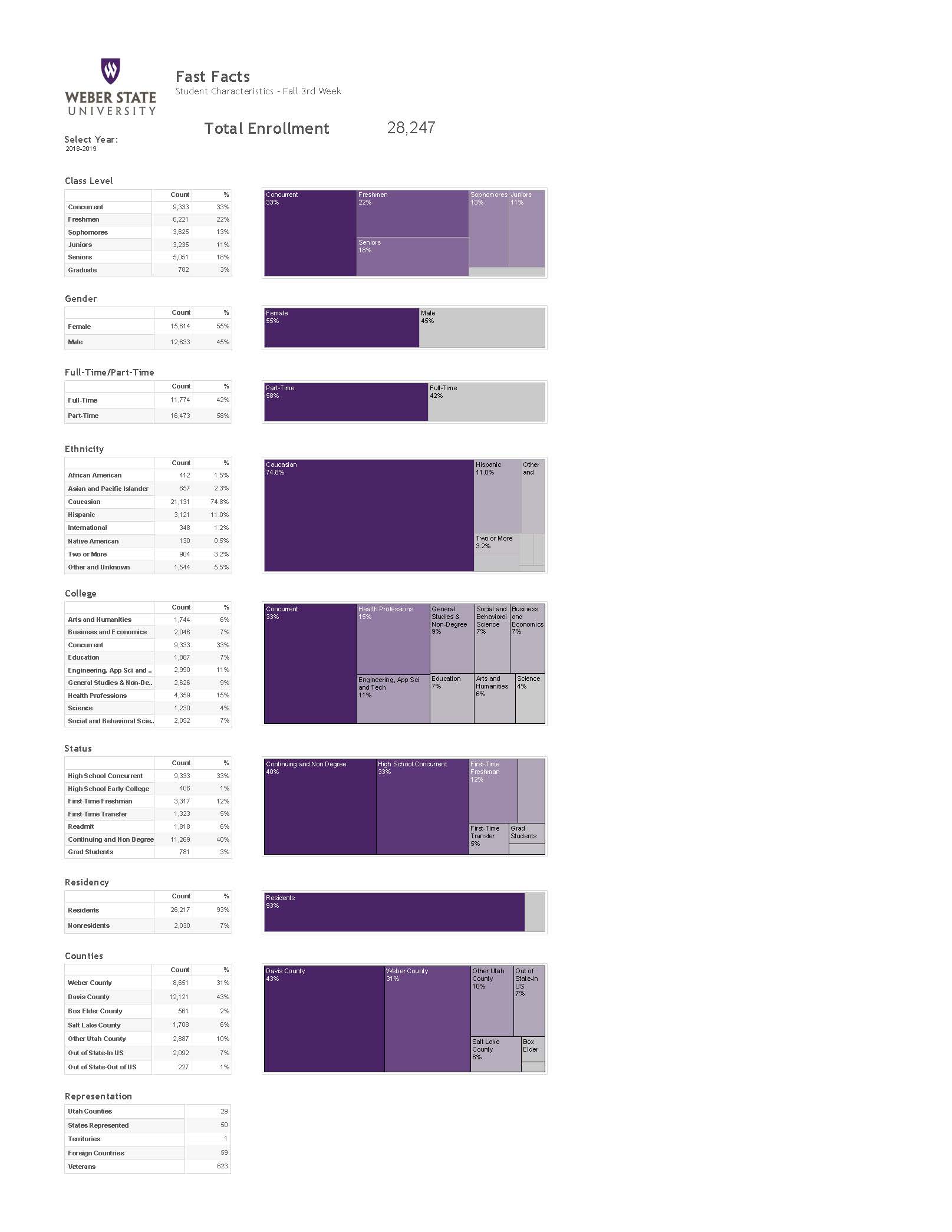

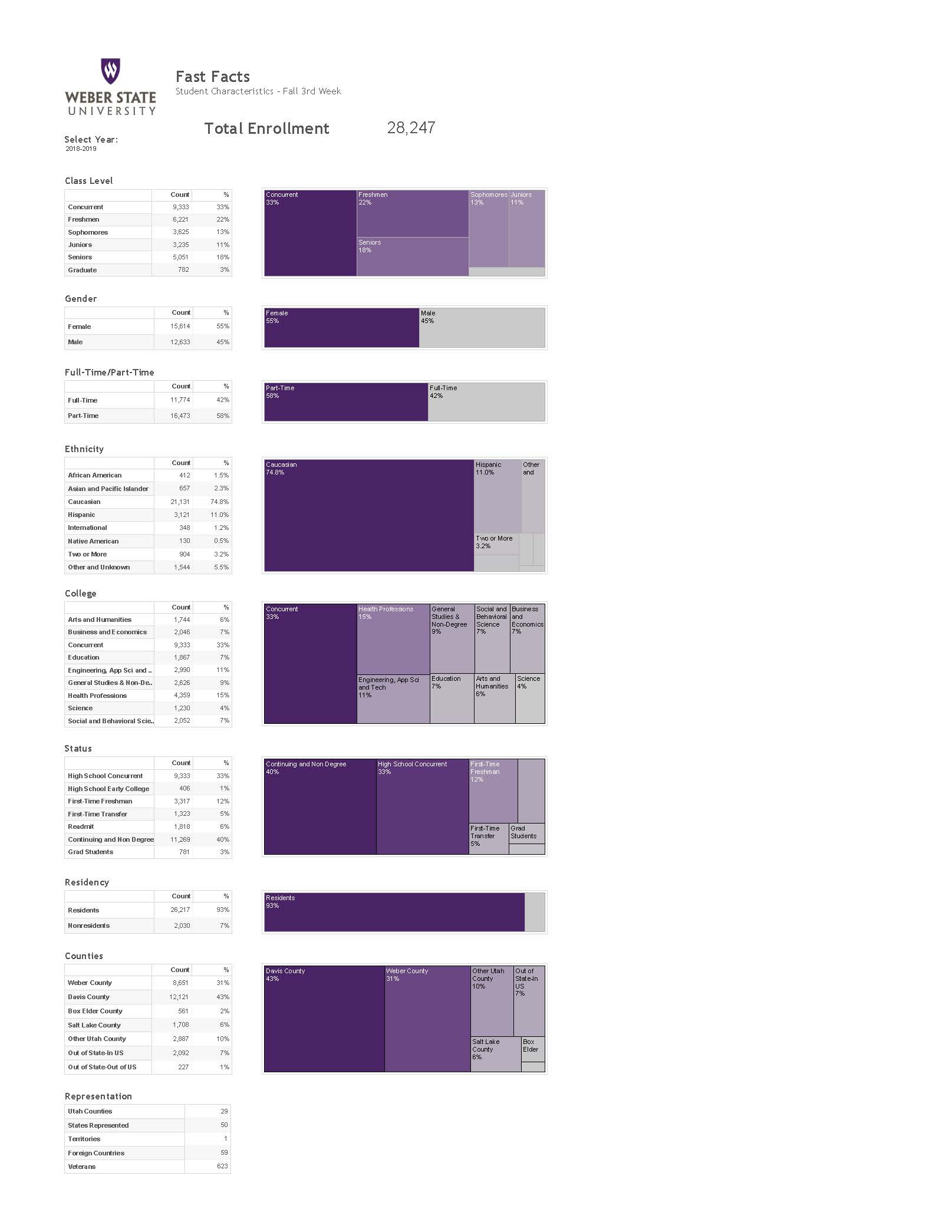

Despite this commitment, the demographics of Ogden City are not currently reflected in WSU’s student demographics: Hispanics comprise 11% of the WSU student population; Asian and Pacific Islanders, 2.3%; and African Americans, 1.5%. It should be noted that WSU attracts students from beyond the Ogden City area (see Appendix); students from multiple counties throughout Utah attend. As a comprehensive public institution with a dual mission that integrates learning, scholarship, and community, WSU aims to provide access to all who wish to pursue higher education. The imbalance in community and campus diversity was a primary impetus for the review of the Lindquist College using the engaged college rubric. The goal is to establish and maintain a symbiotic relationship of service and learning within and for the community. Thus, an assessment regarding levels of college engagement was seen as a potential means for expanding WSU’s service mission.

Objective

As the previously described context shows, WSU’s commitment to community-engaged practices is indisputable. However, the degree to which colleges directly contribute to or become deeply committed to this vision has remained questionable. With the view that the college is a vital unit of analysis, we sought to better understand the college’s engagement activities and culture. Based on WSU’s long-standing commitment to community-engaged learning, a group of faculty within the Lindquist College assessed the college’s level of engagement in the triumvirate of teaching, scholarship, and service. To do so, we utilized Saltmarsh and Middleton’s college-level engagement rubric (see Saltmarsh, Middleton, & Quan, 2019). Additionally, we sought to explore new avenues of community engagement that might be practically implemented at the college level based on our review of rubric indicators.

Methodology

In 2016, as chair of the Rubric Working Group (“the group”), then-Associate Dean Becky Jo Gesteland gathered faculty from each of the five departments within the college who were known as leaders in and/or advocates for community-engaged practices. Because Gesteland was familiar with most of the faculty in the college, she simply asked available and interested faculty to join the group, which would meet regularly throughout the year. The resulting group—the authors of this article—included the following faculty: Isabel Asensio, professor of Spanish; Christy Call, assistant professor of English; Becky Jo Gesteland, professor of English and associate dean; Alexander L. Lancaster, assistant professor of communication; Amanda Sowerby, professor of dance; Kathleen “K” Stevenson, professor of visual art and design. The group met eight times between October 2016 and February 2017, with their collaborative efforts focused primarily on annotating the rubric and rating the college in each of the rubric areas.

The rubric provided a yardstick for evaluating the college across eight dimensions, including leadership and direction; mission and vision; visibility and communication; recognition; rewards; capacity-building infrastructure for support and sustainability; assessment; and curricular pathways (see Saltmarsh et al., 2019). According to the rubric, a college may stand at one of three stages: Stage 1, “Emerging”; Stage 2, “Developing”; or Stage 3, “Transforming.” The group examined all eight dimensions from the rubric to assess the college’s structures, policies, and practices for community-engaged work.

Because the group comprised junior and senior faculty from each of the five departments, there was a strong basis of knowledge for the levels of engaged practices occurring across the college as a whole. We conducted the examination through large group meetings, with all six group members in attendance, and worked systematically through the rubric. When we did not know how to answer one of the indicators, we researched the college website or contacted someone who knew. The group examined each indicator by asking whether or not it applied to the college as a whole or only to individual departments or programs within the college. For example, when analyzing the indicator “Alignment with Accreditation” in the category of Mission and Vision, we discovered that dance, an area within the Department of Performing Arts, requires Community Education, while other areas do not. Going forward, the group will drill deeper into majors within areas and departments.

In addition, since several participants from the college are involved in the pilot group of the university’s HIEE rollout project, the group plans to debrief with the participants at the end of the academic year and collate their results with the ones from the college rubric implementation project. This meeting, facilitated by the associate dean, should help determine next steps for the college and the university, and better define responsibilities assigned to various entities such as programs/areas, departments, colleges, universities, CCEL, etc.

Results and Discussion

With few exceptions, the college generally ranked at Stage 1, “Emerging.” However, the college did rank at a Stage 2, or “Developing,” in 10 of the 48 rubric components. In many cases, group members found that departmental or university policies, resources, and/or practices existed to indicate Stage 2 or 3 performance if the unit of analysis was university-wide efforts. Because CCEL provides so many resources and opportunities, the college is not structured to offer or support many of these initiatives. This finding aligns with the work of Jaeger et al. (2012), who, as mentioned earlier, argued that lasting change bridging campus and community efforts for high-impact teaching and scholarship can only be sustainable if it is implemented and supported throughout the institution, at the level of colleges and departments. This proves to be a critical challenge for WSU, even with its celebrated history of community-engaged work. Thus, the asymmetry of structure, or the fragmentation of efforts, between the campus as a whole and the college as a unit, limits the overall effectiveness of community-engaged learning, teaching, and scholarship.

The group also analyzed the following aspects of CEL work in the college in order to create a set of recommendations for lasting improvement of community-engaged practices.

Faculty Annual Reports at the College Level

One recommendation for incentivizing CEL work among faculty involves recognizing and rewarding such work in the annual reports that faculty submit. Last year, the college added a section in its report template to include recognition of high-impact practices. The following is an excerpt of language taken from the revised report template:

Please describe any teaching, scholarship, and/or service that involved high-impact experiences. The Engagement Subcommittee defines high-impact experiences as involving “student participation in curricular and co-curricular learning activities occurring on a regular basis that are intentionally designed to foster active and integrative learning and student engagement by utilizing multiple impact amplifiers not typically found within an academic setting.”

A review of the results of this effort after the first year of implementation revealed a lack of consensus regarding participation. Several faculty members were uncertain about what “counts” as a high-impact practice (HIP) and claimed that certain practices did not align with the university definition. Others did not list any HIPs, even though we knew they frequently provided such experiences for students. This feature in the annual report will take more time to become recognized and understood.

Faculty Training and Mentoring at the University Level

Another recommendation from the working group involved creating a community of practice (CoP) focused on community-engaged learning that would be specific to the college. Last year, at the university level, CCEL and the Teaching and Learning Forum created a series of CoPs, two of which focused on CEL (designated 1.0 and 2.0). In its first year, the CoPs for CEL attracted a fair number of faculty participants, though not enough to run two separate groups. The combined cohort included 12 faculty from accounting and taxation, communication, foreign languages, health promotion and human performance, interior design, nursing, social work, and teacher education. The CoP aimed to provide interested faculty with a space to explore community engagement pedagogies, student reflection design, reciprocal partnership building, community research models, and community project design, among other topics. This CoP also gave members the opportunity to network with community partners in the form of field trips to different sites.

The CoP was assessed at the end of the experience. Overall, participants thought that it was a positive and instructive experience. However, they also noted a few limitations or challenges. The first challenge related to identifying and structuring varied CEL “proficiencies.” Faculty participants in the CoP had different expectations and needs based on their different stages of training and experience. Some had never taught a CEL course and needed guidance on pedagogy implementation and course design; others had been doing community-engaged work for years in their classrooms and were more in need of innovative applications and/or new ways to motivate students. Identifying and meeting different levels of proficiency would optimally require more resources in the form of group facilitators.

This point leads to a second challenge: mentorship. Pairing junior faculty with more CEL-experienced faculty, whether within the same department or college, is a noted best practice in the literature, and this would be an ideal project for the Lindquist College. One of the challenges in training faculty in CEL pedagogies, of course, is the lack of incentives and/or compensation, whether for new or experienced faculty. Faculty mentors as well as participants interested in CEL pedagogies confront an obvious time investment in rethinking their instructional approaches, so incentives might generate an increased sense that their efforts are recognized and appreciated. It might also result in higher numbers of participation within a CoP as well as improved retention rates.

Ideally, CCEL will continue to provide general training and professional development for faculty interested in CEL or community-based research. Perhaps each college could create a CoP 2.0 for each disciplinary area.

Other Considerations and Concerns at the University Level and Statewide

Several major changes are impacting the work that the college and university aim to complete:

- The university contract with OrgSync (WeberSync) expired, and, at the end of August 2018, the campus switched to a mobile app (Weber Connect). This new app has a steep learning curve and fewer capabilities, at least currently. For instance, it does not allow for form creation and submission, so the CEL designation application process needed a new home. Fortunately, the chair of the CCEL Curriculum Committee worked with the university curriculum chair to create a CEL designation form in the university curriculum system, Curriculog. The shift to Curriculog represents a form of institutionalization that promises greater buy-in, as department chairs and deans will now be part of the process; although not part of the official CEL designation process, they will be part of the review timeline and thus know who is doing what. This transparency should improve HIEE efforts across campus.

- The executive director of CCEL left WSU in mid-August 2018, and Associate Dean Gesteland was appointed interim director. In April 2019, she was appointed executive director. Meanwhile, Professor Sowerby has been appointed associate director and Professor Asensio has been appointed chair of foreign languages. These changes have assured a relatively seamless transition for continued work on the project.

- The funding for Utah Campus Compact was not renewed by the state legislature, necessitating a regrouping of faculty engagement institutes, among other requirements. While institutions of higher education in Utah explore ways to move forward, the conversations of this “next steps” group afford many opportunities to connect and revise the mission of Weber State University.

Recommendations

The group’s self-assessment indicated that the college is not as engaged as we initially thought. Although the college includes strong individual programs and strong faculty leaders, these programs and people are primarily supported through CCEL. In order to sponsor college-wide initiatives that support engaged learning and that lead to improved structures, policies, and practices, the group proposes several immediate revisions, near-future changes, and long-term strategic shifts.

Immediate Revisions

- Update the annual faculty report form with the new definition of high impact educational experiences and provide examples of some of these practices from the college.

- Use the Engagement Subcommittee’s HIEE taxonomy to evaluate educational practices in the college.

Near-Future Changes

- Collaborate with the Office of Institutional Effectiveness to create a pre/post survey for students about their HIEEs.

- Survey community partners, in collaboration with CCEL.

- Revise the college tenure document to include HIEEs in all three areas: teaching, scholarship, and service.

Long-Term Strategic Shifts

- Include high-impact practices in new faculty job descriptions (Dimensions I and III).

- Designate a point person in each department who serves as a faculty mentor and who can track CEL and other high-impact work.

- Create a college-level academic emphasis or certificate.

- Provide professional development support for faculty who incorporate HIEEs in their teaching.

The group recognizes that these recommendations are part of what needs to be a much larger process at various levels within the university. Indeed, our recommendations apply to the college but also involve “multiple actions in multiple areas” to achieve a truly transformative shift (Saltmarsh et al., 2019). These multiple points of change are especially important to achieve buy-in, since the Engaged Subcommittee discovered that some faculty were not ready; they perceived “community engagement work as a zero-sum equation—if community engagement was being valued, then what I do is not going to be valued.” As the university moves forward with the implementation of the HIEE definition and self-evaluation tool, and as individual faculty members, departments, and college begin piloting the tool, the hope is that everyone can find a place for HIEE in their curriculum. Many of the recommendations are beyond the committee’s or even the college’s control; however, the general movement of the university promises the future incentivization of HIEE and thus CEL work.

Conclusion

The Lindquist College of Arts and Humanities at Weber State University served as a testing area for the engaged college rubric, which led to the committee’s enhanced understanding of the areas in which the college can be an exemplar for the university. Although the college ranked at the “Emerging” level in most areas, the experience with the rubric allowed the committee to develop recommendations that, if implemented, may lead to closer alignment with the university mission of “access, community, and learning.” Specifically, WSU’s goals align naturally with the work of community engagement; it is simply a matter of articulating this alignment more carefully. For instance, community engagement (1) facilitates the ability of members of our community to interface with students, faculty, and staff; (2) builds a shared learning community between the institution and northern Utah entities; and (3) fosters a joint learning initiative among students and their community partners. In the present study, the use of the engaged college rubric facilitated a college-wide discussion on what improvements can be made to increase community engagement in teaching, scholarship, and service areas.

That said, the committee encountered some limitations with the study. First, the committee’s conclusions were based on specific descriptors within the rubric. Throughout the process, the committee had to frequently remind members that the rubric was to be applied at the college level, not the university or departmental level. In doing so, the committee had to decide whether activities at the departmental level, though not directly at the college level, counted as a college effort. In the interest of caution, the committee decided that only descriptors of actions that applied specifically at the college level would be counted for advancing beyond the “Emerging” stage. As a result, the committee may have been overly restrictive in its consideration of the college’s level, according to the rubric. A second limitation involved the experimental nature of the rubric itself. Because the rubric was in beta testing and had not yet been released, it is possible that a final version of the rubric may include updated descriptors. Thus, future research conducted with the engaged college rubric should continue to refine and replicate the present study.

As the college moves forward with the implementation of CEL practices in coursework, data will be collected to identify any potential increases in retention numbers in programs and thereby to determine whether to more fully embrace these methods. These data may be persuasive in encouraging other colleges on campus to begin exploring the rubric, clarify the value of CEL practices to retain students, and increase the depth of knowledge they gain in the process. The university roll-out of the HIEE initiative should assist in data-gathering efforts, since more entities (the Provost’ Office, the Office of Institutional Research, the Center for Community Engaged Learning, and the Lindquist College) will now conduct assessments of how community engagement—and other high-impact practices—affects student success.

Without the commitment of the college, it is difficult for university initiatives to reach all levels, especially front-line areas that perhaps have the most influence in determining student experience. Coupled with departments, the college is a critical site for faculty to engage in discussions and reflections about the way their teaching and scholarship connect to the community. Therefore, the engaged college rubric project serves as an example of how faculty members must often work cooperatively to assess CE involvement and then implement feasible, practical changes that increase the value of engaged work.

References

Bringle, R. G., & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Civic education through service learning: What, how, and why? In L. McIlrath & A. Lyons (Eds.), Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101-124). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. (n.d.). About Carnegie Classification. Retrieved from http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/

da Cruz, C. G. (2018). Community-engaged scholarship: Toward a shared understanding of practice. Review of Higher Education, 41, 147-167.

Demographics. (2019). Ogden, UT. Retrieved from https://www.ogdencity.com/1466/

Demographics

Eckel, P., Green, M., Hill, B., & Mallon, W. (1999). On change III: Taking charge of change: A primer for colleges and universities. An occasional paper series of the ACE Project on Leadership and Institutional Transformation. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Jaeger, A. J., Jameson, J. K., & Clayton, P. (2012). Institutionalization of community-engaged scholarship at institutions that are both land-grant and research universities. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 16, 149-167.

Saltmarsh, J., Giles, D. E., Jr., O’Meara, K., Sandmann, L., Ward, E., & Buglione, S. M. (2009). Community engagement and institutional culture in higher education: An investigation of faculty reward policies at engaged campuses. In B. E. Moely, S. H. Billig, & B. A. Holland (Eds.), Advances in service-learning research. Creating our identities in service-learning and community engagement (pp. 3-29). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Sandmann, L. R., Thornton, C. H., & Jaeger, A. J. (2009). Institutionalizing community engagement in higher education: The first wave of Carnegie classified institutions. Cambridge, MA: Wiley.

Warren, M. R., & Mapp, K. L. (2011). A match on dry grass: Community organizing as a catalyst for school reform. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Appendix

Student Characteristics Fast Facts from the Report Gallery

Authors

Dr. Becky Jo Gesteland is the Executive Director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning and a professor of English at Weber State University. She teaches classes in professional & technical writing and American literature. Her research and writing focus on community-engaged learning, content management (specifically XML), and the personal essay.

Dr. Becky Jo Gesteland is the Executive Director of the Center for Community Engaged Learning and a professor of English at Weber State University. She teaches classes in professional & technical writing and American literature. Her research and writing focus on community-engaged learning, content management (specifically XML), and the personal essay.

Dr. Christy Call is an assistant professor of English at Weber State University. Her research highlights emergent ethical issues in literature from the standpoint of relations in a more-than-human world. Additionally, she directs the English Teaching program, which has centralized community engagement through education, public service, and research.

Dr. Christy Call is an assistant professor of English at Weber State University. Her research highlights emergent ethical issues in literature from the standpoint of relations in a more-than-human world. Additionally, she directs the English Teaching program, which has centralized community engagement through education, public service, and research.

Alexander L. Lancaster (Ph.D., West Virginia University, 2015) is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at Weber State University. He serves as the basic course director for the department, as well as the faculty co-advisor of the Community Research Team, part of the Center for Community Engaged Learning. His primary areas of research interest are persuasion and professional communication.

Alexander L. Lancaster (Ph.D., West Virginia University, 2015) is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at Weber State University. He serves as the basic course director for the department, as well as the faculty co-advisor of the Community Research Team, part of the Center for Community Engaged Learning. His primary areas of research interest are persuasion and professional communication.

Kathleen “K” Stevenson (MFA, University of Notre Dame, 1999) is a professor of art in the Department of Visual Art and Design at Weber State University, and director of printmaking. She has been involved with community engagement for the past decade, bridging the creative arts, education and community in many of its forms, including the establishment of the Beverley T. Sorenson Arts Learning Endowment at WSU in 2013.

Kathleen “K” Stevenson (MFA, University of Notre Dame, 1999) is a professor of art in the Department of Visual Art and Design at Weber State University, and director of printmaking. She has been involved with community engagement for the past decade, bridging the creative arts, education and community in many of its forms, including the establishment of the Beverley T. Sorenson Arts Learning Endowment at WSU in 2013.

Amanda Sowerby is Associate Dean and Professor of Dance within the Lindquist College of Arts and Humanities at Weber State University. Her creative research focuses on dance as a creative tool for transformation within public and non-profit educational environments.

Amanda Sowerby is Associate Dean and Professor of Dance within the Lindquist College of Arts and Humanities at Weber State University. Her creative research focuses on dance as a creative tool for transformation within public and non-profit educational environments.

Dr. Isabel Asensio is professor of Spanish and chair of the Department of Foreign Languages at Weber State University. She serves as faculty adviser for several student clubs and organizations, such as the Hispanic Honor Society and MEChA. Her research focuses on women and gender issues in literature, Translation Studies, and Community Interpreting.

Dr. Isabel Asensio is professor of Spanish and chair of the Department of Foreign Languages at Weber State University. She serves as faculty adviser for several student clubs and organizations, such as the Hispanic Honor Society and MEChA. Her research focuses on women and gender issues in literature, Translation Studies, and Community Interpreting.