Thinking About the Future of Community Engagement Conferences: Community Presence Is Not A Proxy For Reciprocity

Emily M. Janke, Ph.D.

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Author Note

Emily M. Janke, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Peace and Conflict Studies. Director, Institute for Community and Economic Engagement. The University of North Carolina Greensboro.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Emily Janke, 1710 MHRA (Moore Humanities and Research Administration), PO Box 26170, Greensboro, NC 27402-6170. Phone: (336) 256-2578. Email: emjanke@uncg.edu.

Abstract

Community voice, alongside academic voice, is essential to the core community engagement principle of reciprocity—the seeking, recognizing, respecting, and incorporating the knowledge, perspectives, and resources that each partner brings to a collaboration. Increasing the extent to which academic conferences honor reciprocity with community members is important for many reasons. For example, community perspectives often enhance knowledge generation and potentially transform scholarship, practice, and outcomes for all stakeholders. However, community presence and participation at academic conferences tends to be thin despite best intentions and resources generated to support community partner travel. This article relates the author’s experience in organizing an academic conference and explores the differences between community member presence and truly reciprocal university partnerships between local and academic communities.

Keywords: community engagement, academic conferences, community presence, university, reciprocal planning, mutual benefit

Introduction

“Where are all of the community partners?” is a question I frequently hear at community engagement-focused conferences. After all, my colleagues reason, the fundamental goals of community-engaged approaches to teaching, research, and service are to generate positive community and academic outcomes. Thus, conferences intended to build the capacity for the mutually beneficial outcomes associated with community engagement should, at the very least, include community partners and benefit community partners.

However, as someone who has traveled and co-presented with community partners at international and local conferences, I have, over time, hesitated to encourage community colleagues to invest time and resources in most academic conferences. While I am confident that my academic colleagues and I will benefit from hearing about their work and their perspectives, I am less certain that academic conferences are set up to maximize the time of community participants who tend to feel that academic conferences are not useful to them. They find sessions to be too theoretical, or alternately, too context specific and thus not of much practical use. As a result, community partners vote with their feet and often leave the conference immediately after their individual sessions. These colleagues are not anti-intellectual—they are partners who work collaboratively with academics and have agreed to take precious time and spend limited resources to share their ideas with a largely (if not exclusively) academic audience. But the perceived benefit of academic conferences is generally low to community partners, and session attendance is also low.

Such experiences with community partners and the continued scant representation and involvement of community partners in academic, community engagement-focused conferences suggest the need to re-examine assumptions about academic conferences and to explore possible reasons for continued low participation rates among community partners. In this article, I suggest that the low levels of community presence and participation may be directly related to the extent to which conference organizers have practiced reciprocity by including community partners in core aspects of conference planning, implementation, and review.

In this paper, I share my own experience of organizing a local “hub” meeting of an international community engagement-focused conference. I offer my reflections on ways to explore barriers and solutions to fuller participation by community colleagues at academic conferences. I suggest the importance of making explicit the underlying assumptions about one’s intentions for and commitment to community partner involvement in all aspects of conference planning. To maintain focus on my own journey in and reflections on organizing a local hub meeting—and because the article does not present the full scope and outcomes of the main conference (of which the hub campuses were a relatively small part), I leave individuals and organizations un-named.

Mutual Benefit and Reciprocity

Mutual benefit and reciprocity are codified hallmarks of community engagement as these two terms describe partnerships in the Carnegie Foundation’s definition for the elective classification: “for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity” (Carnegie, 2008). Despite their ubiquity in community engagement literature, the terms mutual benefit and reciprocity are often neither clearly articulated nor honorably practiced in many community partnerships (Dostilio, Brackmann, Edwards, Harrison, Kliewer & Clayton, 2012). While the terms are increasingly common, understanding of them remains vague and the practice uneven.

Mutual benefit suggests a win-win relationship. The term speaks to the outcomes anticipated and expected by all parties involved in the activity, initiative, or relationship. In community-university engagement, mutual benefit includes academic outcomes (e.g., student development, scholarly advancement, institutional priorities) and community outcomes (e.g., serving the community organization’s mission and priorities). All stakeholders are expected to achieve meaningful outcomes. Mutual benefit does not imply equal benefit – that each will get the same outcome (Bringle, Clayton, Price, 2009; Bringle & Hatcher, 2002). Rather, mutual benefit suggests equity – that partners achieve the outcomes that are just and meaningful to them.

Beyond mutual benefit, high-quality community/campus partnerships are reciprocal. Reciprocity can be defined as “the recognition, respect, and valuing of the knowledge, perspective, and resources that each partner contributes to the collaboration” (Janke & Clayton, 2011, p. 3). It is distinct from mutual benefit as it moves beyond expectations of complementarity to reposition power so that it is shared among collaborators (Saltmarsh, Hartley & Clayton, 2009). It is a process of “cocreation” (Saltmarsh & Hartley, 2011, p. 20).

In academic and community partnerships, power is often embodied with regards to who is perceived to be the “expert.” Those who are perceived experts are powerful, and those who are not are relatively less powerful. In fully reciprocal partnerships, the power is balanced in such a way that the community and academic partners become true collaborators each bringing his or her own expertise, roles, and expectations and each contributing in meaningful ways to the process and the outcomes.

Beyond civic learning and community outcomes, reciprocity has value for scholarly and epistemological ends. Engaged scholarship has been argued to be “superior research” (Saltmarsh & Zlotkowski, 2011, p. 6, emphasis in original) as it has the potential to transform academic knowledge, learning, processes, outcomes, and even institutions. Saltmarsh and Zlotkowski (2011) point to the scholarship in a variety of disciplines (e.g., neurobiology, cognitive psychology, philosophy of science, anthropology) that demonstrate the effectiveness of an engaged approach in knowledge production and dissemination.

Arguing that inclusion of key stakeholders bridges a critical theory to practice gap, Van de Ven (2007) proposes that stakeholders be involved throughout the four main stages of research: problem formation, problem solving, research design, and theory building. Engaging those who experience or are stakeholders in the area of investigation enhances the validity of theory as well as the “truth (verisimilitude)” (2007, p.10) of the proposed solutions. Engaging those whom the scholarship is meant to serve can improve the validity of the findings and help move ideas out of the academy and into practice in communities. Hence, the greater the community partner involvement, the greater the potential for academic and community transformation. What, then, are academics missing out on when community partners are not among the participants at academic conferences? This article suggests that most conferences on community engagement currently fail in their efforts to attract community partners, in part because of how conference organizers conceptualize inclusion . The following example from my own experience focuses on the difference between presence and reciprocity.

Example

Looking for a way to increase the number of community partners and faculty members from our region and campus who could be part of an international conference on community-university partnerships, I suggested to the conference organizers that our campus could host a “hub” meeting. According to this plan, the office in which I worked would “bring the conference to Greensboro” via videoconference. Rather than just one community partner and one faculty member attending from our community to the main conference, two dozen local faculty, students, staff, and community partners participated in the event.

The main conference organizers agreed to partner with the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) and another institution to pilot the “hub campus” concept. Conference organizers at the two institutions held a series of phone conferences and exchanged numerous e-mails to clarify logistics, develop an agenda , and craft content and handouts for the participants. We passed back and forth drafts of speaking points related to best practices for partnerships. The idea was that the host and hub sites would each prepare its participants in similar ways to ground conversations in best practices throughout the day as we met in our respective sites, and later during the two-hour videoconference when all three sites would watch and respond to a common session featuring an exemplar community-university partnership. While each site would have its own unique participants and discussions throughout most of the day, the common speaking points about best practices and the videoconference would connect all three campuses in a single learning experience.

At the end of several weeks of intensive planning, I sent out an email to the director of a local nonprofit consortium of nearly 300 member organizations. It read:

UNCG is excited to partner with the [conference] to bring a “hub” meeting of the internationally recognized Institute here to Greensboro. This opportunity is offered at no cost to you and was developed to encourage and enhance regional partnerships while connecting to innovative models for developing and understanding community-university relationships. Due to time and budget constraints, we knew that we couldn’t bring everyone we wanted to the Institute [out of state], so we decided to bring a portion of the conference here via webcasting! We will learn with colleagues in [another city], as well as with and from [local community leader] and [local professor] who will be joining us as one of the featured, nationally recognized partnerships.

I then added the following note:

Would you mind sharing this with the [consortium] listserv? I believe I shared this opportunity that I’ve been developing with [name], Senior Scholar at the [National] Foundation and developer of this year’s [conference] at [an out of] State University. It would be great to meet with you to discuss the best strategy to ensure that this meeting is immediately useful to community partners. [The senior scholar] will be sending some speaking points that will be common to the [Institute-based] discussions, but there is room for us to shape it for our own local folks. Would you be willing to help to do this? Perhaps even help to facilitate? I realize that I should have asked this prior to sending this announcement out… Hmm, if you’re interested, I can add you and the [consortium] on the flyer before I send it to the [consortium] and any further… your thoughts?

Moments later, I receive the director’s response:

Emily, our Program Committee meets Wed. I’ll talk with them and get back to you then. I would be happy to help facilitate and I think we will want to be reflected as partners. Wednesday won’t be too late I don’t think.

The next day I received an unsettling email simply stating: “Please call me at [phone number].” I called and the effect of the conversation was that the program planning committee was not willing to co-sponsor the meeting. They did not believe that it would serve their mission: to be directly useful to nonprofits. In my earnestness to provide a high-quality experience in collaboration with a prestigious international conference, I had failed to partner with the individuals and organizations that such a hub meeting was developed to serve. The irony of trying to plan a conference on community-engaged partnerships without community partners was embarrassing, to say the least.

I explained that the intention of the meeting was to provide a service for community members and leaders in Greensboro. If it wasn’t going to be useful to half of the constituents it was intended to serve, then it wasn’t worth doing. I had lobbied the main conference planners to try this “hub” idea, which had already taken up considerable time and money. So, we set up a time for the consortium program planning committee to meet with me and a UNCG colleague.

In the end, we redesigned the UNCG hub portion of the event. The meeting was co-developed and co-facilitated by a community nonprofit leader. The length of the meeting was shorter than originally planned to accommodate the schedules of the nonprofit executive directors. We invited a panel of experienced community and faculty partners to describe their collaborations and to share insights on what makes partnerships succeed or fail. We chose to convene individuals whose work and experience focused on two specific issue areas— refugees and immigrant communities, those experiencing homelessness—rather than sending out an open invitation on the listserv. Narrowing the invitation list to individuals involved in addressing specific issue areas allowed us to initiate a conversation about developing shared research and action agendas. We connected by videoconference with the international conference and the other hub campus for shared learning about an exemplary cross-sector partnership.

The community partners were interested in learning about a national exemplar but were skeptical that focusing solely on that example would be of much use to them locally. They reasoned that the specific context and circumstances, as well as the individuals and local politics involved, were so unique as to be of little use locally.

Rather than a general informational session, the consortium wanted more concrete examples and action-oriented goals. They wanted to be able to walk away with a new connection or opportunity, not just greater awareness. As one community partner explained, the practical reality of many nonprofits is that if the activity does not directly and clearly serve the mission of the nonprofit, it cannot justify the use of the community partner’s time. The emphasis is on tangible results, not on greater understanding, generation, preservation, or dissemination of knowledge. Knowledge needs to be coupled with action.

Following the meeting, UNCG allocated internal funds for partnerships that resulted from the meeting. These funds were a subset of an existing annual community-based research grant program provided by several offices within UNCG. As a result of the conference, six faculty members from five different departments, eight graduate and undergraduate students, and ten nonprofits and community coalition-building groups developed a countywide asset map that identified over 360 assets for refugee and immigrant individuals, families, and service providers. The map provides a visual, as well as searchable, portrait of assets for better coordination among service providers and advocates as well as for gap analysis, the first step in identifying missed opportunities or vulnerabilities (see Sills, 2011 for more information).

Grounded in national and local exemplars, as well as best practices of community-university partnerships (e.g., Community/Campus Partnerships for Health, 2006; Cox, 2000; Enos & Morton, 2003; Freeman, 2000; Holland, 2006; Janke, 2009; Jameson, Clayton & Jaeger, 2010; Reardon, 2005), we developed important insights, networks, and ultimately, collaborations. As a result of the consortium planning committee’s shared design and facilitation of the conference, the hub meeting was changed significantly from the initial plan ultimately leading to strengthened relationships and direct opportunities for shared and sustained learning, scholarship, and action through a community-engaged research project.

Clearly Setting the Aim for Conference Outcomes

Though important community and academic outcomes were achieved as a result of the conference, one of the most important outcomes for me was at the personal level. I developed a deeper and clearer understanding of why community partners might not be inclined to attend academic conferences. Further, I understood that my failure to consider carefully my assumptions about the goals for the meeting had led me to miss the target.

As an educator, I know that the first step in planning successful activities or initiatives is to envision the goals that one expects to accomplish. In curriculum planning, it is called “backwards design” (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). One identifies the outcomes one wishes to achieve and then works backwards, chronologically as well as conceptually, to determine what content and strategy, as well as assessment measures, are required to achieve the anticipated ends.

Researchers typically follow this process as well: identify the question to be addressed, then work backwards to determine what literature needs to be reviewed and what methods are most appropriate. To work backwards, then, is to set a clear vision or goal for what success looks like, before undertaking any other aspect of the curriculum or research plan. In community engagement one of the expected outcomes is mutual benefit—that each party, throughout the duration of the collaborative activity or relationship, achieves self-identified outcomes as a result of having participated.

In the vignette described above, I did not clearly or accurately define the intended outcomes for community involvement. I knew that I wanted to include community partners and benefit community partners through building their capacity to collaborate effectively with members of the university community. I had planned (in my own mind) for mutual benefit, but I had not enacted reciprocity. My conception of inclusion, in this case, could more accurately be described as participation rather than as full inclusion or co-creation. I had simply asked the consortium to help recruit participants to attend the conference. I had used them for marketing because the indicator of success that I had unwittingly defined through a vague understanding of the community outcomes was simply attendance.

My intentions to benefit community partners were not accurately defined because they were neither community-informed nor co-created. They were my assumptions that I applied to an ambiguously defined community. I failed to capture the strength of the community-engaged approach and followed a more traditional applied approach wherein one assumes first and verifies later. I started with my “end” in mind rather than with a co-created vision. I started the process by planning the specifics of the conference rather than the specifics of the outcomes with academic and community partners.

What Does Reciprocal Planning Look Like?

In order for a partnership to be reciprocal, partners must be involved in all steps of a project. To achieve standards of best practice for community-based participatory research (a specific form of community engagement), community partners should participate in identifying the area under inquiry; the selection of questions, approaches, and methods; the interpretation of the data for analysis; the dissemination of the findings; and the review or evaluation of the activities and partnership (Israel, Schulz, Parker & Becker, 1998). In short, the community partner is an integral member throughout all aspects of the work of the research team.

To assume that partners are to be equally involved in all aspects of the project, or in this case, conference, can inadvertently lead to misunderstanding and even exploitation as community members may extend beyond their own interests to preserve the relationship with university members (Janke, Holland & Buchner, 2011). In actual practice, the level and type of involvement may vary over time and according to phase, activity type, purpose, and members involved. How then might one consider and plan a path that is reciprocal, yet avoids exploitation? This question led me to engage in conversation with colleagues including Patti Clayton, Andy Furco, Barbara Holland, Kristin Medlin, Evan Goldstein, and Kathleen Edwards to reflect on the literature and my experiences, and ultimately, to develop the cone of reciprocity in community engagement (herein referred to as the cone of reciprocity).

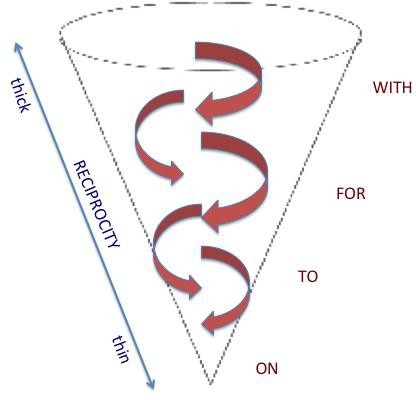

Figure 1. Cone of Reciprocity in Community Engagement Adapted from Furco (2010)

Building on Furco’s (2010) cone of engagement with ideas advanced by Jameson, Clayton, and Jaeger (2010) on thick and thin reciprocity, I developed the cone of reciprocity (Figure 1) as a tool through which to view the ways in which academic and community partners relate to each other throughout the duration of their partnership (or even within a more time limited activity, such as a conference) as multi-dimensional and fluid. The cone can be applied to both long-term and more limited partnerships.

Furco developed the original cone of engagement as a tool to demonstrate the variety of ways that community and university members may interact with one another. The cone moves from a one-way approach in which university members interact with community members for the purpose of collecting research on, to providing a service to or for the community, to a multi-directional and arguably more reciprocal approach in which university and community partners work with one another. At the widest part of the cone, community members may choose to initiate and drive the community/university collaboration. Furco’s cone expresses the continuity of ways in which community and university members may engage with one another. Importantly, it does not create separate categories demarcating an activity as “engaged” or “un-engaged.” Rather, it provides an opportunity to consider the ebbs and flows of projects and relationships and the potential for movement up and down the cone.

I borrowed from Jameson, Clayton, and Jaeger’s (2010) scholarship on thick and thin reciprocity to explore the importance of the phase of activity (e.g., planning, implementation, evaluation, revision), the level of involvement (e.g., thought-based versus technical contributions), and the communication style (e.g., collaborative versus cooperative) in the enactment of reciprocity. Thin reciprocity is characterized by transactional interactions in which partners cooperate minimally with each other to achieve specific and often technical ends. In thinly reciprocal partnerships, partners are likely to invite others once into specific phases or activities of the project. While each partner may achieve the goal or outcome expected, they are not likely to have forged expectations, relationships, or other types of capacities required to initiate future or more complex and transformative collaborations.

On the other end of the spectrum, thick reciprocity is characterized by the mutual exchange of ideas, the collaborative generation of knowledge, shared power, and joint ownership of the full scope of work processes and outcomes. In thickly reciprocal partnerships, partners share and shape ideas together in a generative and collaborative spirit. Thick reciprocity builds understanding among partners and trusting relationships, the foundation for enduring and transformative partnerships.

In the first iteration of planning the local “hub” conference, I collaborated with academic colleagues exclusively, working with community partners only at the time of inviting them to the conference as participants. Assuming that I knew what community partners valued, I worked for weeks for them and on their behalf. Relative to the cone, I was both low and sparse (or thin) in reciprocity because I included them in only one activity (invitation), asked them to serve a technical function (email the consortium listserv), and approached them for their cooperation, not their collaboration.

In the second iteration of planning with community partners (i.e., moving up the cone), my thinking, and the resultant hub conference processes and outcomes, were transformed. In the revised approach to organize the hub conference, community partners were equal collaborators (with) in five stages of the conference activity: (1) designing the outcomes and strategies of the hub conference; (2) inviting participants with relevant interest; (3) facilitating the conversations; (4) composing the evaluation forms; and (5) supporting additional meetings following the conference for those interested in pursuing a community- based research grant. They acted as thought-partners through each of the five stages, crafting the conference with community outcomes in mind, as I kept academic constituent goals in mind. And we collaborated through asking questions and seeking clarity as well as consensus.

While thick reciprocity (Jameson, Clayton & Jaeger, 2010) is important, times of thin reciprocity may be natural and important aspects of reciprocal partnerships. It can, for example, create efficiencies. To save the other partners’ time, one can take a lead role in planning or doing an aspect of the work. In the case of the hub conference described, the university coordinated the logistics of the day including technology, supplies, and food, covered the expenses for the conference and subsequent community-based research grants, and coordinated follow up meetings and shared the participant feedback with the consortium. These were largely technical aspects, not substantive aspects of the conference. We recognized the disparities between partners relative to time and resources available to this particular initiative. Future research on community/university partnerships may map the various elements, such as the phase of activity, the level of involvement, and the communication style onto the cone of reciprocity to empirically test the relationship of these elements to partners’ perceptions of reciprocity within a specific project or a long-term partnership. For example, do partners who are brought onto a project at the very end perceive their relationship to be reciprocal? Do partners who are consulted about technical items only, report reciprocity in the project?

As a scholar and practitioner of community-university partnerships, I know what reciprocity and mutual benefit are as well as the myriad reasons why these principles are essential and just. So how did I miss the mark so entirely in my initial planning for this hub conference? Why had I unconsciously confused or conflated community attendance with reciprocity? While I certainly acknowledge my own agency, I believe that part of the answer may lie in academic culture. I have my own preconceptions about what an academic conference is, and I need to identify and problematize those preconceptions if I am to uphold the principles of reciprocity and mutual benefit.

In an article outlining the importance of interdisciplinary and in-person scientific meetings in a time of increasing specialization and online conference technologies, Alberts (2013) the editor-in-chief of Science argues that the most essential value they serve is the “critical role that face-to-face scientific meetings play in stimulating a random collision of ideas and approaches” (p. 737, emphasis added). He goes on to speak about the importance of personal interactions with individuals who may see things differently given their own unique experiences, trainings, epistemologies, and interests. While he is not specifically describing community engagement conferences, he could be. Arguably, meetings and conferences are important for generating, advancing, sharing, and disseminating ideas because individuals meet and learn from others whose scholarship or activities have important intersections with their own, but which they might not have otherwise discovered.

Beyond sharing and generating ideas, conferences are also important for institutional and individual prestige. A university commits considerable resources to host a conference, in large part because of the recognition it will bring to the campus. Hosting a community-engagement conference signals the commitment of the university to supporting community-university partnerships, thus creating or reiterating the campus’s image and identity (Janke, Medlin and Holland, 2012) as an institution that values and supports specific kinds of scholarship or activity.

At the individual level, hosting or participating in conferences brings eminence. At UNCG, as well as other universities, eminence measures include being the host or chair of a conference and presenting at conferences. Scholars earn tenure and promotion, in part, based on eminence. Presenting at a national or international conference brings more eminence than presenting locally.

Habits for academic conference planning tend to align with the prestige culture at a broader scale: they prioritize the advancement and generation of academically grounded knowledge and often (though not always) rotate among campuses nationally and internationally. One result may be that organizing for community conferences tends to follow traditional models for conference planning and implementation.

It is well documented that the academy presents intense socialization during the years of graduate work that continues as one gains membership in disciplinary as well as institutional ranks (e.g., Dany, Louvel & Valette, 2011; Dill, 1982; Sweitzer, 2008; Traweek, 1988). Graduate students are introduced to schemas (Poole, Gioia, & Gray, 1989), or guidelines, for behavior given specific contexts and situations, that reinforce and reiterate cultural norms about what successful scholars do. Academic cultures tend to emphasize cosmopolitan (Gouldner, 1957) values in which affiliation and reference groups primarily lie outside of an individual’s employing organization and in other professional groups. Cosmopolitans are relatively more oriented to their disciplinary communities and to research than to their collegiate peers or to institutional activities and agendas. Further, as Rhoads, Kiyama, McCormick & Quiroz (2008) point out, communities outside of the academy have not been included in the concept of local until very recently. In an academic prestige culture, the priority is on advancing the disciplinary community; prestige culture does not, in many cases, take the local community (defined as sectors outside of higher education) into account.

Recognizing the strong influence of prestige culture, Barker (2011) urges academics to “resist the assimilation of civic engagement by bureaucratic institutions…. [as] civic engagement initiatives are implemented in the context of institutions that have powerful incentives to copy ‘best practices’ and meet evaluation criteria imposed from above rather than engage in genuine democratic experimentation” (as cited by Saltmarsh & Hartley, p. 9). Speaking of advice given to new professors, especially women and faculty of color, to not get drawn into community engagement activities, Rhoades et al. (2008) find that “(t)he advice is more how to ‘make it’ than how to remake it” (p. 215) in the academy. To what extent are community-engaged scholars and activists repeating the same patterns, enacting and reifying the same schema, in conference planning?

Being Open to Transformation

A second significant challenge is simply being open to transformation, which is to say taking a risk. In my case, I had to be open to changing my preconceived idea of what a local community engagement conference looked like and how it operated. When implemented, true reciprocity promises transformation.

Discussing faculty members’ resistance to accepting community-engaged scholarship as legitimate faculty work, Driscoll (2010) suggests that faculty must address underlying assumptions to get to the heart of implications for community- engaged scholarship. Left unaddressed, transformation may be “derailed” (p. 9). These assumptions include: fear (traditional research would become undervalued and no longer accepted); worry (research/scholarship will lose quality and rigor); avoidance (society’s problems and issues feel insurmountable); overwhelming (preparation takes significant time); discomfort (requires new kinds of relationships); and woe (lack of preparation for fostering community relationships).

With regards to convening community and academic partners at conferences, I would also add the fear of not satisfying community member’s expectations, particularly as it involves future partnerships and action. What if I bring all of these people together and no connection is made? University faculty and staff approach the community as boundary spanners, but they have little control over the choices of the organization, as represented by other organizational members, to follow through.

This required a leap of faith that is not unlike that of a faculty member who decides to move away from pre-determined hypothetical cases to adopt a community-engaged pedagogy. One must fully trust the process as one does not know what the encounter will bring or the outcome it will have. By walking into the community partner’s conference room to co-plan the conference, I knew I had to be willing to go back to my academic colleagues and potentially re-negotiate what we had already decided. It wasn’t that I was going to abandon the outcomes I wanted to achieve but that I needed to find a way that honored community- identified and community-focused ones as well.

To what extent are academics open to the transformation that is possible when all partners genuinely and earnestly seek to understand, value, respect, and incorporate one another’s perspectives into plans for community engagement conferences? Are we willing to change the process for identifying conference hosts, conference planners, session formats, locations, and venues? In what instances should we focus our objectives for a conference on community engagement to achieve academic outcomes only—and at what cost? Continuing to problematize the ways in which we approach planning and organizing academic conferences is not only important but also essential for conferences that purport to support and advocate community engagement.

Conclusion

Discussing the imperative of arts institutions to make substantive changes in their relationship to the wider public, Borwick (2012) argues that the artist community must turn attention to “building communities, not audiences” as the title of his book suggests. The same may be said for conferences that purport to increase capacity for community engagement. We must build communities that truly honor the principles of mutual benefit and reciprocity. We might start to consider how we can “remake” conferences as an exercise in breaking out of schemas that suggest disciplinary ends exclusively and begin practicing, and modeling to others reciprocal community/university partnerships that advance academic as well as community outcomes.

Starting with conference planning, we might identify and remove assumptions that may actually serve as barriers. Modeling how we can transform this one aspect of academia (the academic conference) with the collaboration of likeminded colleagues is important if we are to continue to attempt to transform the academy to embrace community-engaged approaches to research, teaching, and service.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my community colleagues Donna Newton, Erin Stratford Owens and Ruth Anderson for their patience and kind insistence that caused me to examine and problematize my own schema and practices. It is because of them that I have transformed my thinking and practice when working to span institutional boundaries for mutual benefit.

References

Alberts, B. (2013). Designing scientific meetings. Science 339, 737.

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (2002). University-community partnerships: The terms of engagement. Journal of Social Issues 58, 503-516.

Bringle, R. G., Clayton, P. H., & Price, M. F. (2009). Partnerships in service learning and civic engagement. Partnerships: A Journal of Service Learning & Civic Engagement 1, 1-20.

Borwick, D. (2012). Building communities, not audiences: The future of the arts in the United States. Winston-Salem, NC: ArtsEngaged.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. (2008). Classification description: Community engagement elective classification: Classification definition. Retrieved from http://classifications.carnegiefoundation.org/descriptions/community_engagement.php on July 16, 2013.

Community/Campus Partnerships for Health. (1998, revised 2006). Principles of good community-campus partnerships. Seattle, WA: CCPH.

Cox, D. N. (2000). Developing a framework for understanding university- community partnerships. Citiscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 5(1), 9-25.

Dany, F., Louvel, S., & Valette, A. (2011). Academic careers: The limits of the ‘boundaryless approach’ and the power of promotion scripts. Human Relations 64(7), 971-96.

Dill, D. D. (1982). The management of academic culture: Notes on the management of meaning and social integration. Higher Education 11(3), 303-20.

Dostilio, L. D., Brackmann, S. M., Edwards, K. E., Harrison, B., Kliewer, B. W., & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Reciprocity: Saying what we mean and meaning what we say. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 19(1), 17- 32.

Driscoll, A. (2010). Institutional strategies for supporting engaged scholarship.

In Janke, E. M., & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Excellence in community engagement and community-engaged scholarship: Advancing the discourse at UNCG (Vol. 1): 9. Greensboro, NC: University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Accessed from http://communityengagement.uncg.edu/pdfs/Speaker_Series_Report_FIN AL_3_12_12.pdf on March 22, 2013.

Enos, S., & Morton, K. (2003). Developing a theory and practice of campus- community partnerships. In B. Jacoby & Associates, Building partnerships for service-learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Freeman, E. R. (2000). Engaging a university: The CCHERS experience. Metropolitan Universities 11(2), 20- 27.

Furco, A. (2009, March). Enhancing institutional engagement: Redefining community involvement in higher education, Keynote Address, Montana Campus Compact; Missoula, MT.

Gouldner, A. W. (1957). Cosmopolitans and locals: Towards an analysis of latent social roles. Administrative Science Quarterly 2(3), 281-306.

Holland, B. (2005). Reflections on community-campus partnerships: What has been learned? What are the next challenges? In P. Pasque, R. Smerek, B. Dwyer, N. Bowman, & B. Mallory (Eds.) Higher education collaboratives for community engagement and improvement, 10-17. Ann Arbor, MI: National Forum on Higher Education for the Public Good.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health 19, 173-202.

Jameson, J., Clayton, P., & Jaeger, A. (2010). Community engaged scholarship as mutually transformative partnerships. In L. Harter, J. Hamel-Lambert, & J. Millesen (Eds.), Participatory partnerships for social action and research. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Janke, E. M. (2008). Shared partnership identity between faculty and community partners, Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University.

Janke, E. M. (2009). Defining characteristics of partnership identity in faculty- community partnerships. In B. Moely, S. Billig, & B. Holland (Eds.), Advances in service-learning research (Vol. 9): Creating our identities in service-learning and community engagement, 75-101. Charlotte, NC: IAP- Information Age Publishing.

Janke, E. M., & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Excellence in community engagement and community-engaged scholarship: Advancing the discourse at UNCG (Vol. 1), Greensboro, NC: University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Janke, E. M. & Hayes, S. (2009). Engaged faculty perceptions of promotion and tenure and department culture to support community-engaged scholarship. (unpublished study).

Janke, E. M., Holland, B., & Buchner, K. (2011). Interactive workshop on research methodologies: Power in partnerships: Advanced methods to research and assess power, processes, and outcomes in community- university partnership. Pre-Conference Session. International Association for Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement Conference, Chicago, IL.

Janke, E., Buchner, K., & Holland, B. (2012). The essential and scholarly role of web‐supported community engagement databases in identity and image management for institutional cultural change. Conference Session.

International Association for Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement Conference, Baltimore, MD.

Poole, M. S., Gioia, D., & Gray, B. (1989). Influence modes, schema change, and organizational transformation. Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences, 25, 271-289.

Reardon, K. M. (2005). Straight A’s: Evaluating the success of community/university development partnerships. Communities & Banking, Summer, 3-10.

Rhoads, G., Kiyama, J. M., McCormick, R., & Quiroz, M. (2008). Local cosmopolitans and cosmopolitan locals: New models of professionals in the academy. The Review of Higher Education, 31(2), 209-35.

Saltmarsh, J. (2010). Building on our success as a community engaged university.Presentation given at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Saltmarsh, J., & Hartley, M. (2011). Democratic engagement. In To serve a larger purpose: Engagement for democracy and the transformation of higher education by Saltmarsh & Hartley (Eds.), 14-24. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Saltmarsh, J., Hartley, M., & Clayton, P. (2009). Democratic engagement white paper. Boston, MA: New England Resource Center for Higher Education.

Saltmarsh, J., & Zlotkowski, E. (2011). Introduction: Putting into practice the civic purposes of higher education. In Higher Education and Democracy: Essays on Service-Learning and Civic Engagement by Saltmarsh and Zlotkowski (Eds.), 1-8. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Sills, S. J. (2011). Mapping a collaborative: Development of a community asset map for Guilford County Refugee and Immigrant Services. Retrieved March 22, 2013 from http://stephensills.wordpress.com/2011/07/15/mapping-a-collaborative- development-of-a-community-asset-map-for-guilford-county-refugee-and- immigrant-services/.

Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Networking to develop a professional identity: A look at the first-semester experience of doctoral students in business. In New Directions for Teaching and Learning. Special Issue: Educating Integrated Professionals: Theory and Practice on Preparation for the Professoriate, 113, 43–56.

Traweek, S. (1988). Beamtimes and Lifetimes: The world of high energy physicists. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. (Expanded 2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Author Biography

Emily M. Janke is the founding Director of the Institute for Community and Economic Engagement (ICEE) and an associate professor in the Peace and Conflict Studies Department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her teaching and scholarship explores multiple aspects of community engagement, including community/university relationships and partnerships, institutional culture and strategies for change, and the role of reciprocity, communication, and tension in win-win negotiations and collaborative relationships. As the director of ICEE, Emily leads initiatives that encourage, support, elevate, and amplify faculty, staff, student, and community colleague community-engaged teaching, learning, research, creative activity, and service in ways that promote the strategic goals of the university, address pressing issues in the Piedmont Triad, and serve the public good of communities across the state, the nation, and the world.